[2011] Qcat 437

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. from Indicators to Report Card Grades

Authorship statement This Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership (GHHP) Technical Report was written based on material from a number of separate project reports. Authorship of this GHHP Technical Report is shared by the authors of each of those project reports and the GHHP Science Team. The team summarised the project reports and supplied additional material. The authors of the project reports contributed to the final product. They are listed here by the section/s of the report to which they contributed. Oversight and additional material Dr Mark Schultz, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Mr Mac Hansler, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Water and sediment quality (statistical analysis) Dr Murray Logan, Australian Institute of Marine Science Seagrass Dr Alex Carter, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Kathryn Chartrand, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Jaclyn Wells, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Michael Rasheed, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Corals Mr Paul Costello, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Angus Thompson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Johnston Davidson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mangroves Dr Norman Duke, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Jock Mackenzie, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Fish health (CQU) Dr Nicole Flint, Central Queensland University -

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

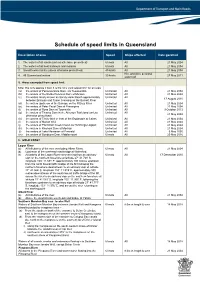

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Apportionment of Dam Safety Upgrade Costs

Consultation paper Rural irrigation price review 2020–24: apportionment of dam safety upgrade costs October 2018 © Queensland Competition Authority 2018 The Queensland Competition Authority supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Queensland Competition Authority has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright2 and this material remains unaltered. Queensland Competition Authority Contents SUBMISSIONS Closing date for submissions: 22 February 2019 Public involvement is an important element of the decision-making processes of the Queensland Competition Authority (QCA). Therefore submissions are invited from interested parties concerning it developing and applying an appropriate approach for apportioning dam safety upgrade capital expenditure as part of the review of irrigation prices for 2020–24. The QCA will take account of all submissions received within the stated timeframes. Submissions, comments or inquiries regarding this paper should be directed to: Queensland Competition Authority GPO Box 2257 Brisbane Q 4001 Tel (07) 3222 0555 Fax (07) 3222 0599 www.qca.org.au/submissions Confidentiality In the interests of transparency and to promote informed discussion and consultation, the QCA intends to make all submissions publicly available. However, if a person making a submission believes that information in the submission is confidential, that person should claim confidentiality in respect of the document (or the relevant part of the document) at the time the submission is given to the QCA and state the basis for the confidentiality claim. The assessment of confidentiality claims will be made by the QCA in accordance with the Queensland Competition Authority Act 1997, including an assessment of whether disclosure of the information would damage the person’s commercial activities and considerations of the public interest. -

Gladstone Area Water Board: Investigation of Pricing Practices

Final Report Gladstone Area Water Board: Investigation of Pricing Practices September 2002 Queensland Competition Authority Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 8 2.1 The Direction 8 2.2 Monopoly Prices Oversight 9 2.3 Approach to Investigation 9 2.4 Structure of the Report 10 2.5 Limitations 10 3. GLADSTONE AREA WATER BOARD’S PRICING PRACTICES 11 3.1 Commercialisation 11 3.2 Description of the Business 11 3.3 GAWB’s Pricing Policy 12 4. DEMAND PROJECTIONS FOR GAWB 15 4.1 Introduction 15 4.2 History of Water Demand 15 4.3 Previous Estimates of Gladstone Water Demand 17 4.4 Stakeholder Comment 18 4.5 QCA Analysis 19 5. THE FRAMEWORK FOR MONOPOLY PRICES OVERSIGHT 23 5.1 Background 23 5.2 Efficient Pricing 24 5.3 Revenue Adequacy 27 5.4 Pricing Practices during Drought and other Force Majeure Events 28 5.5 Differential Pricing 32 5.6 Pricing for Seasonal Demand Variations 39 6. THE ASSET BASE 41 6.1 Introduction 41 6.2 Optimisation 44 6.3 Contributed Assets 56 6.4 Recreational Assets 59 6.5 Environmental Assets 60 6.6 Working Capital 61 6.7 Land and Easements 62 6.8 Relocated Assets 64 i Queensland Competition Authority Table of Contents 7. RATE OF RETURN 67 7.1 Introduction 67 7.2 Issues in Determining the Rate of Return Framework 68 7.3 Issues in the Selection of a WACC Equation 69 7.4 Quantifying the Risk Free Rate 73 7.5 Quantifying the Market Risk Premiu m 77 7.6 Determining the Capital Structure 80 7.7 Determining the Cost of Debt 82 7.8 Determining Equity and Asset Betas 83 7.9 Determining the Dividend Imputation Rate 89 7.10 Determining the Tax Rate 91 7.11 Expected Inflation 92 7.12 Deriving the WACC 93 8. -

Species Line Wt Angler Club Location Area Date Archer Fish 1 1.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Tinaroo Cairns 5/01/1996 Barramundi 1 13.000 K

Impoundment Sportfishing - Open Species Line Wt Angler Club Location Area Date Archer Fish 1 1.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Tinaroo Cairns 5/01/1996 Barramundi 1 13.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Awoonga Brisbane 28/12/2005 Barramundi 2 12.280 J. Tratt Ipswich United Kinchant Dam Mackay 11/03/2005 Barramundi 3 17.300 J. Leighton Cairns Lake Tinaroo Cairns 26/05/1995 Barramundi 4 17.000 J. Leighton Cairns Lake Tinaroo Cairns 2/01/1996 Barramundi 6 10.230 E. Hodge Bundaberg Lake Monduran Gin Gin 28/10/2007 Bass (Australian) 1 2.790 N. Schultz SEQTAR Somerset Dam Brisbane 8/01/1997 Bass (Australian) 2 2.720 T. Wilson North Brisbane North Pine Dam Brisbane 13/05/2001 Bass (Australian) 3 2.200 B. Harvey North Brisbane Somerset Dam Brisbane 4/02/1995 Catfish Eel-Tail 2 2.360 H. Johnson Townsville Salties Lake Monduran Gin Gin 19/08/2008 Catfish (Freshwater) 1 2.600 O. Rose Toowoomba Cooby Dam Toowoomba 24/12/1996 Catfish Forktail (salmon) 2 3.620 H. Johnson Townsville Salties Lake Monduran Gin Gin 19/08/2008 Cod (Murray) 2 4.600 N. Schultz SEQTAR Leslie Dam Warwick 16/10/1994 Cod (Murray) 3 10.500 N. Schultz SEQTAR Leslie Dam Warwick 15/01/1995 Cod (Murray) 4 3.800 L. O'Rielly Bribie Island Glenlyon Dam Stanthorp 29/09/1989 Cod (Murray) 6 8.350 R. Mackay Toowoomba Leslie Dam Warwick 3/07/1993 Grunter (Sooty) 1 2.650 B. Weston Hinchinbrook Lake Prosepine Prosepine 26/09/2010 Grunter (Sooty) 2 3.330 J. -

Final Report Seqwater Irrigation Price Review 2013-17 Volume 1

Final Report Seqwater Irrigation Price Review 2013-17 Volume 1 April 2013 Level 19, 12 Creek Street Brisbane Queensland 4000 GPO Box 2257 Brisbane Qld 4001 Telephone (07) 3222 0555 Facsimile (07) 3222 0599 [email protected] www.qca.org.au The Authority wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the following staff to this report Matt Bradbury, William Copeman, Ralph Donnet, Mary Ann Franco-Dixon, Les Godfrey, Angus MacDonald, George Passmore, Matthew Rintoul and Rick Stankiewicz © Queensland Competition Authority 2013 The Queensland Competition Authority supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Queensland Competition Authority has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Queensland Competition Authority Glossary GLOSSARY A AAP Annual Accounts Payable AAR Annual Account Renewable ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics ACCC Australian Competition and Consumer Commission ACG Allen Consulting Group ACT Australian Capital Territory ACTEW Australian Capital Territory Electricity and Water ADWG Australian Drinking Water Guidelines AER Australian Energy Regulator AMF Asset Management Framework ARMCANZ Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand ARR Asset Restoration Reserve ASSET PLANS Asset Plans outline proposed capital and operating expenditure to deliver an entities’ Service Level Agreements. AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is Australia's official statistical organisation. AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY The Australian Capital Territory Electricity and Water (ACTEW) ELECTRICITY AND WATER Corporation supplies energy, water, and sewerage services to the ACT and surrounding region. -

Technical Report

Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership TECHNICAL REPORT | GLADSTONE HARBOUR REPORT CARD 2016 ISBN 978-0-646-96339-6 9 > 780646 963396 Authorship statement This Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership (GHHP) Technical Report was written based on material from a number of separate project reports. Authorship of this GHHP Technical Report is shared by the authors of each of those project reports and the GHHP Science Team, which summarised the project reports and wrote additional material. The authors of the project reports contributed to the final product, and are listed here by the section/s of the report to which they contributed. Oversight and additional material Dr Mark Schultz, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Dr Uthpala Pinto, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Water and sediment quality, Statistical analysis Dr Murray Logan, Australian Institute of Marine Science Seagrass habitats Ms Alex Carter, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Catherine Bryant, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Jaclyn Davies, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Michael Rasheed, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Coral habitats Mr Angus Thompson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Paul Costello, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Johnston Davidson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Fish (Bream Recruitment) Mr Bill Sawynok, Infofish Australia Dr Bill Venables, Private Consultant -

Table of Contents About This Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 About this report 3 About us 4 CEO’s review 5 Chairman’s outlook 6 Performance highlights 8 Review of operations 20 SunWater organisational structure 21 SunWater Board 24 SunWater executive management team 26 Directors’ report 28 Auditor’s independence declaration 29 Financial report 68 Corporate governance 72 Compliance in key areas 74 Summary of other SCI matters 76 Scheme statistics 79 SunWater dam statistics 80 Glossary 82 SunWater operations and infrastructure 2016 ABOUT THIS REPORT This Annual Report provides a review of SunWater’s financial and non-financial performance for the 12 months ended 30 June 2016. The report includes a summary of activities undertaken to meet key performance indicators as set out in SunWater’s Statement of Corporate Intent 2015–16 (SCI). The SCI represents our performance agreement with our shareholding Ministers and is summarised on pages 8 to 18, 74 and 75. This annual report aims to provide accurate information to meet the needs of SunWater stakeholders. An electronic version of this annual report is available on SunWater’s website: www.sunwater.com.au We invite your feedback on our report. Please contact our Corporate Relations and Strategy team by calling 07 3120 0000 or email [email protected]. 2 SUNWATER ANNUAL REPORT 2015-16 ABOUT US SunWater Limited owns, operates and facilitates the development of bulk water supply infrastructure, supporting more than 5000 customers in the agriculture, local government, mining, power generation and industrial sectors. The map at the back of this report illustrates The main operating companies within SunWater’s water supply network also SunWater’s extensive regional presence SunWater, and their activities, include: supports Queensland’s mining sector, in Queensland and highlights our existing • Eungella Water Pipeline P/L (EWP) supplying water to some of Queensland’s infrastructure network, including: owns and operates a 123 km-long largest mining operations. -

BURNETT BASIN !! Dalby# !!( #!

!! !! !! !! !! !! !!!! !! ! !! I ve r!!a gh C !! re #!! Smoky Creek ek Middle Creek !! CRAIGLANDS IVERAGH !( Goovigen !! !! SEVENTEEN ek AL !! e #AL/TM ! Basin Locality r UPPER !SPRINGS Legend SEVENTY Y # !( C MARLUA BOROREN-IVERAGH p JAMBIN BELL CK AL Seventeen Seventy ! ! W !! AL/TM RAIL TM ! m ! ! ! ( Qld border, a AL H k k #! ! Townsville # C !! Automatic rainfall station (RN) FERNDALE C UPPER!! C MT MONGREL ! coastline C N (! a O RAINBOW AL C er AL !! Bowen ll S A tt Manual/Daily rainfall station (DN) Basin i LL u Bororen!( k d W IO F boundary e A CALLIDE DAM C P MT SEAVIEW m THREE MILE CK (! D lu !!! MILTON Automatic river height station (RV) k # INFLOW AL/TM E ! g * CAPTAIN CK Mackay !AL i TM !! e # # D AL/TM ! EDEN e Callide MALAKOFF R ! AL/TM D r ! MIRIAM VALE !! WESTWOOD e ! JUNCTION AL/TM A AL # Manual river height station (RV)ep e C ! # ! TM! /MAN RANGE AL w Dam # ! l N # l KROOMBIT !( a i # m G Nagoorin !! t i v LINKES C REPEATER AL NAGOORIN B e k ! ! ! Miriam Vale r e ! ! e CALLIDE DAM ! E BOOLAROO D !(!! # a Forecast site (quantitative) h ! N CAUSEWAY AL/TM ! eg #AL/TM f RAPLEYS ! KROOMBIT f l a # ! ( DA MOUNT lg k ! l ! C ! ! il l W HW AL/TM TOPS AL/TM ALLIGAT+OR ( Biloela ! # C e k Emerald Rockhampton e S KROOMBIT TOPS AL/TM !! #AL/TM # FLATS AL S it O Y !. Kr b ! KROOMBIT DAM AL, B C MFAoKrOeWcaATsAt CsKit e (qualitaE tive) !! !! oo m ! ! S R o !! N W !BILOELA ! !!! ! A !! y o ! u H ! !LOVANDEE HW/TW TM k ! CEDAR + TM E N n l # o l ! HILLVIEW QLD C s # e ! ! G e RED HILL Kroombit# k VALE AL !RseC!.uk !( MAKOWATA i ( -

Annual Report 2012

Gladstone Area Water Board Annual Report Table of contents Chairperson’s letter ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 Chairperson’s review ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 Overview of the year ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 4 Board of Directors’ profiles. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Review ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 9 Goals for 2012/2013 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 18 Governance ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 19 Governance – Board and Committees ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 21 Governance – Human Resources ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 23 Governance – Reporting ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 24 Governance – Other significant issues... ... ... ... ... ... ... 25 Five year summary. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 26 Financial statements ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 28 Glossary... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 62 Chairperson’s letter Reply please quote ref: 189637 The Honourable Mark McArdle MP The Minister for Energy and Water Supply PO Box 15216 City East Brisbane Qld 4002 Dear Minister I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2011-2012 and financial statements for the Gladstone Area Water Board. I certify that this Annual Report complies with: » the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009; and » the detailed requirements set out in the Annual Report Requirements for Queensland Government -

Record of Proceedings

PROOF ISSN 1322-0330 RECORD OF PROCEEDINGS Hansard Home Page: http://www.parliament.qld.gov.au/hansard/ E-mail: [email protected] Phone: (07) 3406 7314 Fax: (07) 3210 0182 Subject FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-THIRD PARLIAMENT Page Thursday, 25 November 2010 PRIVILEGE ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 4333 Alleged Deliberate Misleading of the House by a Minister ................................................................................................. 4333 SPEAKER’S STATEMENTS .......................................................................................................................................................... 4333 Answers to Questions on Notice ........................................................................................................................................ 4333 Answers to Questions on Notice; Ministerial Responses to Petitions ................................................................................ 4333 Our Lady of the Rosary School Choir ................................................................................................................................. 4333 Hash House Harriers, Red Dress Run ............................................................................................................................... 4334 PETITIONS .................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Fisheries (Freshwater) Management Plan 1999

Queensland Fisheries Act 1994 Fisheries (Freshwater) Management Plan 1999 Reprinted as in force on 13 June 2008 Reprint No. 3B This reprint is prepared by the Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel Warning—This reprint is not an authorised copy Information about this reprint This plan is reprinted as at 13 June 2008. The reprint shows the law as amended by all amendments that commenced on or before that day (Reprints Act 1992 s 5(c)). The reprint includes a reference to the law by which each amendment was made—see list of legislation and list of annotations in endnotes. Also see list of legislation for any uncommenced amendments. This page is specific to this reprint. See previous reprints for information about earlier changes made under the Reprints Act 1992. A table of reprints is included in the endnotes. Also see endnotes for information about— • when provisions commenced • editorial changes made in earlier reprints. Spelling The spelling of certain words or phrases may be inconsistent in this reprint due to changes made in various editions of the Macquarie Dictionary. Variations of spelling will be updated in the next authorised reprint. Dates shown on reprints Reprints dated at last amendment All reprints produced on or after 1 July 2002, authorised (that is, hard copy) and unauthorised (that is, electronic), are dated as at the last date of amendment. Previously reprints were dated as at the date of publication. If an authorised reprint is dated earlier than an unauthorised version published before 1 July 2002, it means the legislation was not further amended and the reprint date is the commencement of the last amendment.