Assessing the Risk of Mimosa Pigra Spread from Peter Faust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2. from Indicators to Report Card Grades

Authorship statement This Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership (GHHP) Technical Report was written based on material from a number of separate project reports. Authorship of this GHHP Technical Report is shared by the authors of each of those project reports and the GHHP Science Team. The team summarised the project reports and supplied additional material. The authors of the project reports contributed to the final product. They are listed here by the section/s of the report to which they contributed. Oversight and additional material Dr Mark Schultz, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Mr Mac Hansler, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Water and sediment quality (statistical analysis) Dr Murray Logan, Australian Institute of Marine Science Seagrass Dr Alex Carter, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Kathryn Chartrand, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Jaclyn Wells, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Michael Rasheed, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Corals Mr Paul Costello, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Angus Thompson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Johnston Davidson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mangroves Dr Norman Duke, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Jock Mackenzie, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Fish health (CQU) Dr Nicole Flint, Central Queensland University -

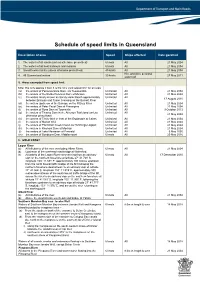

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

Gladstone Area Water Board: Investigation of Pricing Practices

Final Report Gladstone Area Water Board: Investigation of Pricing Practices September 2002 Queensland Competition Authority Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 2. INTRODUCTION AND OBJECTIVES 8 2.1 The Direction 8 2.2 Monopoly Prices Oversight 9 2.3 Approach to Investigation 9 2.4 Structure of the Report 10 2.5 Limitations 10 3. GLADSTONE AREA WATER BOARD’S PRICING PRACTICES 11 3.1 Commercialisation 11 3.2 Description of the Business 11 3.3 GAWB’s Pricing Policy 12 4. DEMAND PROJECTIONS FOR GAWB 15 4.1 Introduction 15 4.2 History of Water Demand 15 4.3 Previous Estimates of Gladstone Water Demand 17 4.4 Stakeholder Comment 18 4.5 QCA Analysis 19 5. THE FRAMEWORK FOR MONOPOLY PRICES OVERSIGHT 23 5.1 Background 23 5.2 Efficient Pricing 24 5.3 Revenue Adequacy 27 5.4 Pricing Practices during Drought and other Force Majeure Events 28 5.5 Differential Pricing 32 5.6 Pricing for Seasonal Demand Variations 39 6. THE ASSET BASE 41 6.1 Introduction 41 6.2 Optimisation 44 6.3 Contributed Assets 56 6.4 Recreational Assets 59 6.5 Environmental Assets 60 6.6 Working Capital 61 6.7 Land and Easements 62 6.8 Relocated Assets 64 i Queensland Competition Authority Table of Contents 7. RATE OF RETURN 67 7.1 Introduction 67 7.2 Issues in Determining the Rate of Return Framework 68 7.3 Issues in the Selection of a WACC Equation 69 7.4 Quantifying the Risk Free Rate 73 7.5 Quantifying the Market Risk Premiu m 77 7.6 Determining the Capital Structure 80 7.7 Determining the Cost of Debt 82 7.8 Determining Equity and Asset Betas 83 7.9 Determining the Dividend Imputation Rate 89 7.10 Determining the Tax Rate 91 7.11 Expected Inflation 92 7.12 Deriving the WACC 93 8. -

Species Line Wt Angler Club Location Area Date Archer Fish 1 1.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Tinaroo Cairns 5/01/1996 Barramundi 1 13.000 K

Impoundment Sportfishing - Open Species Line Wt Angler Club Location Area Date Archer Fish 1 1.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Tinaroo Cairns 5/01/1996 Barramundi 1 13.000 K. Behrens Brisbane Lake Awoonga Brisbane 28/12/2005 Barramundi 2 12.280 J. Tratt Ipswich United Kinchant Dam Mackay 11/03/2005 Barramundi 3 17.300 J. Leighton Cairns Lake Tinaroo Cairns 26/05/1995 Barramundi 4 17.000 J. Leighton Cairns Lake Tinaroo Cairns 2/01/1996 Barramundi 6 10.230 E. Hodge Bundaberg Lake Monduran Gin Gin 28/10/2007 Bass (Australian) 1 2.790 N. Schultz SEQTAR Somerset Dam Brisbane 8/01/1997 Bass (Australian) 2 2.720 T. Wilson North Brisbane North Pine Dam Brisbane 13/05/2001 Bass (Australian) 3 2.200 B. Harvey North Brisbane Somerset Dam Brisbane 4/02/1995 Catfish Eel-Tail 2 2.360 H. Johnson Townsville Salties Lake Monduran Gin Gin 19/08/2008 Catfish (Freshwater) 1 2.600 O. Rose Toowoomba Cooby Dam Toowoomba 24/12/1996 Catfish Forktail (salmon) 2 3.620 H. Johnson Townsville Salties Lake Monduran Gin Gin 19/08/2008 Cod (Murray) 2 4.600 N. Schultz SEQTAR Leslie Dam Warwick 16/10/1994 Cod (Murray) 3 10.500 N. Schultz SEQTAR Leslie Dam Warwick 15/01/1995 Cod (Murray) 4 3.800 L. O'Rielly Bribie Island Glenlyon Dam Stanthorp 29/09/1989 Cod (Murray) 6 8.350 R. Mackay Toowoomba Leslie Dam Warwick 3/07/1993 Grunter (Sooty) 1 2.650 B. Weston Hinchinbrook Lake Prosepine Prosepine 26/09/2010 Grunter (Sooty) 2 3.330 J. -

Final Report Seqwater Irrigation Price Review 2013-17 Volume 1

Final Report Seqwater Irrigation Price Review 2013-17 Volume 1 April 2013 Level 19, 12 Creek Street Brisbane Queensland 4000 GPO Box 2257 Brisbane Qld 4001 Telephone (07) 3222 0555 Facsimile (07) 3222 0599 [email protected] www.qca.org.au The Authority wishes to acknowledge the contribution of the following staff to this report Matt Bradbury, William Copeman, Ralph Donnet, Mary Ann Franco-Dixon, Les Godfrey, Angus MacDonald, George Passmore, Matthew Rintoul and Rick Stankiewicz © Queensland Competition Authority 2013 The Queensland Competition Authority supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of information. However, copyright protects this document. The Queensland Competition Authority has no objection to this material being reproduced, made available online or electronically but only if it is recognised as the owner of the copyright and this material remains unaltered. Queensland Competition Authority Glossary GLOSSARY A AAP Annual Accounts Payable AAR Annual Account Renewable ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics ACCC Australian Competition and Consumer Commission ACG Allen Consulting Group ACT Australian Capital Territory ACTEW Australian Capital Territory Electricity and Water ADWG Australian Drinking Water Guidelines AER Australian Energy Regulator AMF Asset Management Framework ARMCANZ Agriculture and Resource Management Council of Australia and New Zealand ARR Asset Restoration Reserve ASSET PLANS Asset Plans outline proposed capital and operating expenditure to deliver an entities’ Service Level Agreements. AUSTRALIAN BUREAU OF STATISTICS The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) is Australia's official statistical organisation. AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY The Australian Capital Territory Electricity and Water (ACTEW) ELECTRICITY AND WATER Corporation supplies energy, water, and sewerage services to the ACT and surrounding region. -

Technical Report

Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership TECHNICAL REPORT | GLADSTONE HARBOUR REPORT CARD 2016 ISBN 978-0-646-96339-6 9 > 780646 963396 Authorship statement This Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership (GHHP) Technical Report was written based on material from a number of separate project reports. Authorship of this GHHP Technical Report is shared by the authors of each of those project reports and the GHHP Science Team, which summarised the project reports and wrote additional material. The authors of the project reports contributed to the final product, and are listed here by the section/s of the report to which they contributed. Oversight and additional material Dr Mark Schultz, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Dr Uthpala Pinto, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Water and sediment quality, Statistical analysis Dr Murray Logan, Australian Institute of Marine Science Seagrass habitats Ms Alex Carter, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Catherine Bryant, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Jaclyn Davies, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Michael Rasheed, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Coral habitats Mr Angus Thompson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Paul Costello, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Johnston Davidson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Fish (Bream Recruitment) Mr Bill Sawynok, Infofish Australia Dr Bill Venables, Private Consultant -

Annual Report 2012

Gladstone Area Water Board Annual Report Table of contents Chairperson’s letter ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 Chairperson’s review ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 2 Overview of the year ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 4 Board of Directors’ profiles. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7 Review ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 9 Goals for 2012/2013 ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 18 Governance ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 19 Governance – Board and Committees ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 21 Governance – Human Resources ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 23 Governance – Reporting ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 24 Governance – Other significant issues... ... ... ... ... ... ... 25 Five year summary. ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 26 Financial statements ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 28 Glossary... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 62 Chairperson’s letter Reply please quote ref: 189637 The Honourable Mark McArdle MP The Minister for Energy and Water Supply PO Box 15216 City East Brisbane Qld 4002 Dear Minister I am pleased to present the Annual Report 2011-2012 and financial statements for the Gladstone Area Water Board. I certify that this Annual Report complies with: » the prescribed requirements of the Financial Accountability Act 2009 and the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2009; and » the detailed requirements set out in the Annual Report Requirements for Queensland Government -

Fisheries (Freshwater) Management Plan 1999

Queensland Fisheries Act 1994 Fisheries (Freshwater) Management Plan 1999 Reprinted as in force on 13 June 2008 Reprint No. 3B This reprint is prepared by the Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel Warning—This reprint is not an authorised copy Information about this reprint This plan is reprinted as at 13 June 2008. The reprint shows the law as amended by all amendments that commenced on or before that day (Reprints Act 1992 s 5(c)). The reprint includes a reference to the law by which each amendment was made—see list of legislation and list of annotations in endnotes. Also see list of legislation for any uncommenced amendments. This page is specific to this reprint. See previous reprints for information about earlier changes made under the Reprints Act 1992. A table of reprints is included in the endnotes. Also see endnotes for information about— • when provisions commenced • editorial changes made in earlier reprints. Spelling The spelling of certain words or phrases may be inconsistent in this reprint due to changes made in various editions of the Macquarie Dictionary. Variations of spelling will be updated in the next authorised reprint. Dates shown on reprints Reprints dated at last amendment All reprints produced on or after 1 July 2002, authorised (that is, hard copy) and unauthorised (that is, electronic), are dated as at the last date of amendment. Previously reprints were dated as at the date of publication. If an authorised reprint is dated earlier than an unauthorised version published before 1 July 2002, it means the legislation was not further amended and the reprint date is the commencement of the last amendment. -

Tillegra Dam Effects on Dungog Council Road Network Infrastructure

Tillegra Dam Effects on Dungog Council Road network infrastructure Greg McDonald September 2007 Amended July 2008 1 Pavement Design Basics Road pavements are designed for a finite life. When the designer needs to determine a design life for the road they typically choose a period of approximately 20 to 30 years. Having a design life, the designer then needs to determine the number of Equivalent Standard Axles (ESAs) that the road is anticipated to carry in that design period, and this figure can then be used to determine a pavement thickness. A ‘Standard Axle’ is a design equivalent to enable various differently loaded axles to be factored into the pavement design. It takes into effect the load and axle configuration of heavy vehicles. The standard axle in which all others are related is a single axle load of 8.2 tonnes (80 kN) on dual tyres. For vehicles that have different axle loadings, the equivalent loading can be calculated from the following formula: 4 NESA = [Pc / PESA) Where: Pc load on axle group PESA load on standard axle group For a motor car of approximately 1.6 tonne (standard Falcon or Commodore) the load on each axle group is approximately 800 kg. 4 NESA = (0.9/8.2) = 0.14 = 0.0001 Tillegra Dam – Road Improvements 2 (or 1 10,000th of an equivalent standard axle) So 1 car is equivalent to about 10,000 trucks! Because cars are so insignificant when compared to heavy vehicles, the design method for calculating total ESAs ignores normal traffic and only utilizes the heavy vehicle traffic. -

Model By-Law: Recreational Areas Regulatory Impact Statement

Department of Sustainability and Environment Model By-Law: Recreational Areas Regulatory Impact Statement This Regulatory Impact Statement has been prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 and the Victorian Guide to Regulation August 2012 MODEL BY-LAW: RECREATIONAL AREAS REGULATORY IMPACT STATEMENT The Minister for Water, the Hon. Peter Walsh MLC is proposing to issue a model by-law for the management of lands deemed under the Water Act 1989 (the Water Act) to be recreational areas under the management and control of Victoria’s water corporations. Section 287Y of the Water Act sets out the necessary process the Minister must apply prior to issuing a model by-law This Regulatory Impact Statement (RIS) has been prepared to fulfil the requirements of the Water Act in facilitating public consultation on the proposed Model By-law: Recreational Areas (the proposed By-law) and to address the requirements under the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 where a water corporation decides to adopt the proposed By-law to make a recreational by-law. In accordance with the Victorian Guide to Regulation , the Victorian Government seeks to ensure that proposed regulations (including by-laws) are well-targeted, effective and appropriate, and impose the lowest possible burden on Victorian business and the community. The prime function of the RIS process is to help members of the public comment on proposed regulatory instruments before they have been finalised. Such public input can provide valuable information and perspectives, and thus improve the overall quality of the regulations (including by-laws). The proposed By-law makes a model by-law which can be drawn upon by water corporations. -

Gladstone Area Water Board

Gladstone Area Water Board Submission to the Queensland Competition Authority Fitzroy River Contingency Infrastructure Page 1 of 117 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 1 Introduction 13 1.1 Background 13 1.2 Water demands and supplies 13 1.3 Constraints in response 14 1.4 Need for new approach 15 1.5 Nature of the proposal put forward in this submission 15 1.6 Structure of this report 17 PART A – BACKGROUND MATTERS 18 2 Gladstone Area Water Board 19 2.1 Background 19 2.2 Role and functions 19 2.3 Responsibilities 20 2.4 Supply relationships 22 2.5 Water supplies and demands in the region 24 3 Drought management planning 28 3.1 Background 28 3.2 Drought risk – entitlements vs contractual supply framework 28 3.3 Previous drought 28 3.4 Drought management plan 30 4 Water supply planning 34 4.1 Introduction 34 4.2 GAWB’s demand and supply environment 34 4.3 Emerging demands 37 4.4 GAWB’s supply profile 38 4.5 Regulation, planning and infrastructure investment 39 4.6 New project investment – Gladstone region 41 4.7 Emerging water supply and planning models in Australia 42 5 Strategic Water Plan 48 5.1 Background 48 GLADSTONE AREA WATER BOARD Page 2 of 117 5.2 Project initialisation 48 5.3 Consultation 48 5.4 Key findings of the strategy 49 5.5 Current status 49 5.6 Regional water supply planning – Central Queensland 50 6 Previous regulatory investigations and outcomes 53 6.1 Previous decisions 53 6.2 Supply augmentation - demand response 53 6.3 Drought response 54 6.4 Ex-post optimisation 55 6.5 Implications for this review 56 PART B – PRUDENCE -

Capital Expenditure Review (Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd)

Appendix 3 RETURN TO APPENDICES LIST Capital Expenditure Review (Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd) CAPITAL EXPENDITURE REVIEW Job No: R1081-06 Prepared for: Gladstone Area Water Board Dated: October 2009 CAPIITAL EXPENDITURE REVIIEW Brisbane Office Rockhampton Office Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd ABN 57 051 074 992 ABN 57 051 074 992 Level 11 Green Square North Tower 1 Aquatic Place 515 St Paul’s Terrace North Rockhampton Qld 4701 Fortitude Valley Qld 4006 PO Box 3174 Locked Bag 4006 Fortitude Valley Rockhampton Shopping Fair Queensland 4006 Australia Queensland 4701 Australia Telephone: 07 3369 9822 Telephone: 07 4924 7500 Facsimile: 07 3369 9722 Facsimile: 07 4926 4375 International: +61 7 3369 9822 International: +61 7 4924 7500 [email protected] Email: [email protected] www.cardno.com.au Web: www.cardno.com.au Document Control Version Date Author Reviewer Name Initials Name Initials 1 - DRAFT September 2009 Chris Hegarty John Graham 2 – DRAFT October 2009 Chris Hegarty John Graham/Natalie Muir FINAL 3 – DRAFT October 2009 Chris Hegarty John Graham/Natalie Muir FINAL 2 4 - FINAL October 2009 Chris Hegarty John Graham/Natalie Muir "© 2009 Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd All Rights Reserved. Copyright in the whole and every part oF this document belongs to Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd and may not be used, sold, transFerred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or Form or in or on any media to any person without the prior written consent oF Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd.” Gladstone Area Water Board Version 4 FINAL Capital Expenditure Review N:\Projects\R1081 - GAWB\06-Capital Expenditure Review\Report Final\GAWB 2009 Capital Expenditure Review Final.doc Cardno (Qld) Pty Ltd Page i CAPIITAL EXPENDITURE REVIIEW TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.