Model By-Law: Recreational Areas Regulatory Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019–2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 Annual Report

2019–2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 Annual report MOUNT ISA WATER BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 A This annual report provides information about MIWB’s financial and non-financial performance during 2019–20. The report describes MIWB’s performance in meeting the bulk water needs of existing customers and ensuring the future bulk water needs of North West Queensland are identified and met. The report has been prepared in accordance with the Financial Accountability Act 2009, which requires that all statutory bodies prepare annual reports and table them in the Legislative Assembly each financial year; the Financial and Performance Management Standard 2019, which provides specific requirements for information to be disclosed in annual reports; other legislative requirements and the Queensland Government’s Annual Report requirements for Queensland Government agencies for 2019–20. This report has been prepared for the Minister for Natural Resources, Mines and Energy to submit to Parliament. It has also been prepared to inform stakeholders including Commonwealth, state and local governments, industry and business associations and the community. MIWB is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have difficulty in understanding the annual report, you can contact MIWB on (07) 4740 1000 and an interpreter will be arranged to effectively communicate the report to you. Mount Isa Water Board proudly acknowledges Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and their rich culture and pays respect to their Elders past, present and emerging. We acknowledge Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as Australia’s first peoples and as the Traditional Owners and custodians of the land and water on which we rely. -

NW Queensland Water Supply Strategy Investigation

NW Queensland Water Supply Strategy Investigation Final Consultant Report 9 March 2016 Document history Author/s Romy Greiner Brett Twycross Rohan Lucas Checked Adam Neilly Approved Brett Twycross Contact: Name Alluvium Consulting Australia ABN 76 151 119 792 Contact person Brett Twycross Ph. (07) 4724 2170 Email [email protected] Address 412 Flinders Street Townsville QLD 4810 Postal address PO Box 1581 Townsville QLD 4810 Ref Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Methodology 2 2.1 Geographic scope and relevant regional characteristics 2 2.2 Situation and vulnerability analysis 3 2.3 Multi criteria decision analysis 5 2.3.1 The principles of multi criteria decision making 5 2.3.2 Quantitative criteria 7 2.3.3 Qualitative criteria 8 3 Situation analysis: Water demand and supply 12 3.1 Overview 12 3.2 Urban water demand and supply 14 3.2.1 Mount Isa 14 3.2.2 Cloncurry 15 3.3 Mining and mineral processing water demand and supply 16 3.3.1 Mount Isa precinct 16 3.3.2 Cloncurry precinct 17 3.4 Agriculture 18 3.5 Uncommitted water 19 3.6 Projected demand and water security 19 3.7 Vulnerability to water shortages 20 4 Water infrastructure alternatives 21 4.1 New water storage in the upper Cloncurry River catchment 23 4.1.1 Cave Hill Dam 23 4.1.2 Black Fort Dam 25 4.1.3 Painted Rock Dam 26 4.1.4 Slaty Creek 27 4.1.5 Combination of Black Fort Dam and Slaty Creek 27 4.2 Increasing the capacity of the Lake Julius water supply 28 4.3 Utilising currently unused water storage infrastructure 30 4.3.1 Corella Dam 30 4.3.2 Lake Mary Kathleen 31 5 Ranking -

Chapter 3. Landscape, People and Economy

Chapter 3. Landscape, people and economy Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning 3. Landscape, people and economy This chapter provides a brief description of the landscape, people and economic drivers in the water resource plan areas. Working rivers The rivers of these water resource plan areas provide many environmental, economic, and social benefits for Victorian communities. Most of northern Victoria’s rivers have been modified from their natural state to varying degrees. These modifications have affected hydrologic regimes, physical form, riparian vegetation, water quality and instream ecology. Under the Basin Plan it is not intended that these rivers and streams be restored to a pre-development state, but that they are managed as ‘working rivers’ with agreed sustainable levels of modification and use and improved ecological values and functions. 3.1 Features of Victorian Murray water resource plan area The Victorian Murray water resource plan area covers a broad range of aquatic environments from the highlands streams in the far east, to the floodplains and wetlands of the Murray River in the far west of the state. There are several full river systems in the water resource plan area, including the Kiewa and Mitta Mitta rivers. Other rivers that begin in different water resource plan areas converge with the River Murray in the Victorian Murray water resource plan area. There are a significant number of wetlands in this area, these wetlands are managed by four catchment management authorities (CMAs): North East, Goulburn Broken, North Central and Mallee and their respective land managers. The Victorian Murray water resource plan area extends from Omeo in the far east of Victoria to the South Australian border in the north west of the state. -

SES Generic Document Vertical

Mount Alexander Shire FLOOD EMERGENCY PLAN A Sub-Plan of the Municipal Emergency Management Plan For Mount Alexander Shire Council and VICSES Unit Castlemaine Version 2, July 2019 “Intentionally Blank”. Mount Alexander Shire Flood Emergency Plan – A Sub-Plan of the MEMP ii Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................ iii Distribution of MFEP ........................................................................................................................................ v Document Transmittal Form / Amendment Certificate ................................................................................. v List of Abbreviations & Acronyms ................................................................................................................. vi Part 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 Approval and Endorsement .................................................................................................................... 7 1.2 Purpose and Scope of this Flood Emergency Plan ................................................................................ 8 1.3 Municipal Flood Planning Committee (MFPC) ....................................................................................... 8 1.4 Responsibility for Planning, Review & Maintenance of this Plan .......................................................... -

2. from Indicators to Report Card Grades

Authorship statement This Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership (GHHP) Technical Report was written based on material from a number of separate project reports. Authorship of this GHHP Technical Report is shared by the authors of each of those project reports and the GHHP Science Team. The team summarised the project reports and supplied additional material. The authors of the project reports contributed to the final product. They are listed here by the section/s of the report to which they contributed. Oversight and additional material Dr Mark Schultz, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Mr Mac Hansler, Science Team, Gladstone Healthy Harbour Partnership Water and sediment quality (statistical analysis) Dr Murray Logan, Australian Institute of Marine Science Seagrass Dr Alex Carter, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Kathryn Chartrand, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Ms Jaclyn Wells, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Michael Rasheed, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Corals Mr Paul Costello, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Angus Thompson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mr Johnston Davidson, Australian Institute of Marine Science Mangroves Dr Norman Duke, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Dr Jock Mackenzie, Tropical Water & Aquatic Ecosystem Research, James Cook University Fish health (CQU) Dr Nicole Flint, Central Queensland University -

Strategic Framework December 2019 CS9570 12/19

Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy Queensland bulk water opportunities statement Part A – Strategic framework December 2019 CS9570 12/19 Front cover image: Chinaman Creek Dam Back cover image: Copperlode Falls Dam © State of Queensland, 2019 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. Under this licence you are free, without having to seek our permission, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. For more information on this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The Queensland Government shall not be liable for technical or other errors or omissions contained herein. The reader/user accepts all risks and responsibility for losses, damages, costs and other consequences resulting directly or indirectly from using this information. Hinze Dam Queensland bulk water opportunities statement Contents Figures, insets and tables .....................................................................iv 1. Introduction .............................................................................1 1.1 Purpose 1 1.2 Context 1 1.3 Current scope 2 1.4 Objectives and principles 3 1.5 Objectives 3 1.6 Principles guiding Queensland Government investment 5 1.7 Summary of initiatives 9 2. Background and current considerations ....................................................11 2.1 History of bulk water in Queensland 11 2.2 Current policy environment 12 2.3 Planning complexity 13 2.4 Drivers of bulk water use 13 3. -

Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River

Lead Pathways Study – Water Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River 2 Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation – Sustainable Minerals Institute Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River Lead Pathways Study – Water Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River 11 May 2012 Report by: Barry Noller1, Trang Huynh1, Jack Ng2, Jiajia Zheng1, and Hugh Harris3 Prepared for: Mount Isa Mines Limited Private Mail Bag 6 Mount Isa 1 Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation, The University of Queensland, Qld 4072 2 National Research Centre for Environmental Toxicology, The University of Queensland Qld 4008 3 School of Chemistry and Physics, The University of Adelaide SA 5005 Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation – Sustainable Minerals Institute 3 Sources and Pathways of Contaminants to the Leichhardt River This report was prepared by the Centre for Mined Land Rehabilitation, Sustainable Minerals Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Queensland 4072. The report was independently reviewed by an environmental chemistry specialist, Dr Graeme Batley. Dr Graeme Batley, B.Sc. (Hons 1), M.Sc, Ph.D, D.Sc Chief Research Scientist in CSIRO Land and Water’s Environmental Biogeochemistry research program Dr Graeme Batley is the former director and co-founder of the Centre for Environmental Contaminants Research (CECR), a program that brings together CSIRO’s extensive expertise in research into the contamination of waters, sediments and soils. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Australian Chemical Institute, member Australasian Society for Ecotoxicology and Foundation President and Board Member of the Society of Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry (SETAC) Asia/Pacific. -

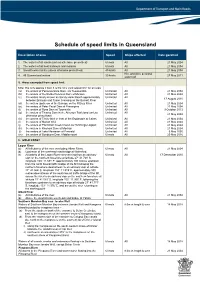

Schedule of Speed Limits in Queensland

Schedule of speed limits in Queensland Description of area Speed Ships affected Date gazetted 1. The waters of all canals (unless otherwise prescribed) 6 knots All 21 May 2004 2. The waters of all boat harbours and marinas 6 knots All 21 May 2004 3. Smooth water limits (unless otherwise prescribed) 40 knots All 21 May 2004 Hire and drive personal 4. All Queensland waters 30 knots 27 May 2011 watercraft 5. Areas exempted from speed limit Note: this only applies if item 3 is the only valid speed limit for an area (a) the waters of Perserverance Dam, via Toowoomba Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (b) the waters of the Bjelke Peterson Dam at Murgon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (c) the waters locally known as Sandy Hook Reach approximately Unlimited All 17 August 2010 between Branyan and Tyson Crossing on the Burnett River (d) the waters upstream of the Barrage on the Fitzroy River Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (e) the waters of Peter Faust Dam at Proserpine Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (f) the waters of Ross Dam at Townsville Unlimited All 9 October 2013 (g) the waters of Tinaroo Dam in the Atherton Tableland (unless Unlimited All 21 May 2004 otherwise prescribed) (h) the waters of Trinity Inlet in front of the Esplanade at Cairns Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (i) the waters of Marian Weir Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (j) the waters of Plantation Creek known as Hutchings Lagoon Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (k) the waters in Kinchant Dam at Mackay Unlimited All 21 May 2004 (l) the waters of Lake Maraboon at Emerald Unlimited All 6 May 2005 (m) the waters of Bundoora Dam, Middlemount 6 knots All 20 May 2016 6. -

A Review of the Distribution, Status and Ecology of the Star Finch Neochmia Ruficauda in Queensland

AUSTRALIAN 278 BIRD WATCHER AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1998, 17, 278-289 A Review of the Distribution, Status and Ecology of the Star Finch Neochmia ruficauda in Queensland by GLENN H.OLMES, P.O. Box 1246, Atherton, Queensland 4883 Summary The Star Finch Neochmia ruficauda has been recorded in 35-37 one-degree blocks in Queensland. Most records concern the Edward River, Princess Charlotte Bay and Rockharnpton districts. Viable populations are probably now restricted to Cape York Peninsula. Typical habitat comprises grasslands or grassy open woodlands, near permanent water or subject to regular inundation. Some sites support shrubby regrowth caused by the clearing of formerly unsuitable denser woodlands. Recorded food items are all seeds, of five grass species and one sedge. Precise nest records are few, but large numbers of juveniles have been observed during the last two decades at Aurukun, Pormpuraaw, Kowanyarna and Princess Charlotte Bay. Threatening processes are discussed; livestock grazing in riparian situations is considered the most deleterious. Introduction The distribution, status and ecology of the Star Finch Neochmia ruficauda in Queensland require urgent review. Endemic to northern and eastern Australia, its populations have declined in most regions. Available evidence suggests that the greatest contraction in its distribution has occurred in Queensland (e.g. Blakers et al. 1984). It is extinct in New South Wales, but its distribution there was only oflirnited extent (Holmes 1996). The Star Finch is protected stringently in Queensland because it is gazetted as Endangered under the Nature Conservation Act 1992. This categorisation takes due account of 'biological vulnerability, extent of current knowledge ... and management needs'. -

DRAFT Fire Operation Plan

LAKE BAEL BAEL LAKE ELIZABETH LITTLE LAKE BAEL BAEL Culgoa REEDY LAGOON SANDHILL LAKE PELICAN LAKECOH005 FOSTERS SWAMP LAKE WANDELLA HORSE SHOE LAGOON DRY LAKE LAKE GILMOUR DRAFT Cohuna LAKE MURPHY TRAGOWEL SWAMP Mathoura Towaninny Fire Operation Plan GREAT SPECTACLE LAKE LITTLE SPECTACLE LAKE Quambatook ROUND LAKE Tragowel Nullawil LITTLE LAKE Curyo TOBACCO LAKELake Meering C A MURRAY GOLDFIELDS L D E LAKE MERAN R H IG H W A Leitchville 2010-2011 TO 2012-2013 Y Woomboota BARMAH LAKE Gunbower GRIFFITH LAGOON KOW SWAMP LAKE LEAGHUR Birchip Picola M UR RAY VA LLE Y H Barmah IGH WAY Torrumbarry ECO034 Pyramid Hill Nathalia ECO031 ECO032 Wycheproof THUNDERBIRD LAKE ECO029 Boort ECO027 ECO028 Moama LAKE LYNDGER ECO016 Durham Ox LITTLE LAKE BOORT Echuca LAKE BOORT Glenloth LAKE MARMAL Watchem LEWIS SWAMP LAKE TERRAPPEE Corack East WOOLSHED SWAMP MURRAY VALLEY HIGHWAY Wyuna Mitiamo ECO014 Tongala Strathallan COXONS SWAMP Y Lockington HWA HIG BORUNG HIGHWAY UNG Charlton Undera BOR LAKE BULOKE Borung BORUNG HIGHWAY Kyabram LITTLE LAKE BULOKE SALT SWAMP LAKE GIL GIL Korong Vale Rochester ECO025 Dingee SKINNERS FLAT RESERVOIR ECO026 Donald Yeungroon Girgarre Serpentine ING055 WAY L IGH O D H Wedderburn IDLAN D M D O GREEN LAKE N Drummartin Stanhope V A L L Corop E Y H I G H Cope Cope W A Y Elmore LAKE COOPER S U ECO021 N R A Y LAKE STEWART S C ECO022 IA AL D H ER I LAKE BATYO CATYO G HI Raywood H GH W W ECO023 A AY Y Y BGO127 A W H G WARANGA BASIN WALKERS LAKE I H D HOLLANDS LAKE ING050 N A L Inglewood D I RSH032 M Y A Colbinabbin RSH033 W H LEGEND -

North Central CMA Region Loddon River System Environmental Water Management Plan

North Central CMA Region Loddon River System Environmental Water Management Plan EWMP Area: Loddon River downstream of Cairn Curran Reservoir and including Tullaroop Creek downstream of Tullaroop Reservoir, Serpentine Creek, Twelve Mile Creek and Pyramid Creek Document History and Status Date Date Version Prepared By Reviewed By Issued Approved 1 (Ch 1-3) 27/2/15 Jon Leevers Louissa Rogers 15/3/15 1 (Ch 7-9) 12/3/15 Jon Leevers Louissa Rogers 17/3/15 1 (Whole) 13/4/15 Louissa Rogers Emer Campbell 17/4/15 DELWP (Melanie Tranter on behalf of Suzanne Witteveen, 2 17/4/15 Louissa Rogers 5/5/15 Susan Watson) Project Steering Committee (PSC), Community Advisory Group 3 21/5/15 Louissa Rogers 29/5/15 (CAG) 4 2/6/15 Louissa Rogers Emer Campbell 5/6/15 5 5/6/15 Louissa Rogers DELWP FINAL Distribution Version Date Quantity Issued To 1 (Ch 1-3) 27/2/15 1 Louissa Rogers 1 (Ch 7-9) 12/3/15 1 Louissa Rogers 1 (Whole) 13/4/15 1 (electronic) Emer Campbell 2 17/4/15 1 (electronic) DELWP (Suzanne Witteveen, Susan Watson) 3 21/5/15 ~35 PSC, CAG 4 2/6/15 1 (electronic) Emer Campbell 5 5/6/15 1 DEWLP (FINAL) Document Management Printed: 23/06/2015 4:35:00 PM Last saved: 9/06/2015 5:05:00 PM File name: Loddon River EWMP.docx Authors: Louissa Rogers and Jon Leevers Name of Organisation: North Central CMA Name of Document: North Central CMA Region Environmental Water Management Plan for the Loddon River System Document version: Version 5 SharePoint link: NCCMA-63-41009 For further information on any of the information contained within this document contact: -

Annual Report

1958 VICTORIA COUNTRY ROADS BOARD FORTY -FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT FOR YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE, 1957 PRESENTED TO BOTH HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT PURSUANT TO ACT No. 3!lo:.!. {&pp1'oximate Oo•t or Report.-Preparation, not. given. Printing (1050 CO!JlOO), iGlU. I By Autbomy: W. M. HOUSTON, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, MELBOURNE. No. 6-(2s. 9d.J-I2035f57. DUAL HIGHWAY COt'-JSTRUCTION Frontispiece :- Princes Highway West, at Kororoit Creek- Duplication of pavement and construction of new bridge o n new alignment. COUNTRY ROADS BOARD FORTY-FOURTH ANNUAL REPORT, 1956-57 CONTENTS FINANCE-- Boanl ';,; I:;(HU'eP;; of reve1rue 7 Commonwealth Aiu Hoa<ls I<'und,.; 8 Loan Moneys expen<liture .. 8 Total allocation for works 9 :\ llocation of fnnds. 1 ~150~57 9 :'-lAIN ROADS ~\llocation of funds 9 ~\ pportionment of costs lO Particulars of works carried out 10 STATI'J HIGHWAYS--~ .\llocation of funds 12 Pai'ticulars of works •·arried onl 12 'fol:HISTs' RoADs---· Allocation nJ fnwb FOREIOTS HoADS--~ "\!location of fund;; 19 IJNCLASSIFU~D HOADS-- ;\pplications from Councils 19 ,\m(nmts allotted l9 BRim:ms- [mpron:ment in eonsttnction progrmmtw 19 ~Ietropolitan bridges 21 ( :<•untry bridge" 21 Ji'Loon DAJ\1AGJ<.:- .:Ifost seriously affected areas 22 1\pplicat.ions receh•ed and grants made 22 Particulars of works carried out 22 HAlLWAY LEVEL CROSSfN(1S- ProjeetR .. 25 \V OltKo FOR OTHER AU'l'HORITH;S- Particulars of works carrie<l out 25 Schedule of expen(litUI·e 20 .SoLDili:R Sl<:TTLE:111EKT EsTATB HoADt> Bxpenditure rlm·ing 1950-57 27 Expenditure ,;ince inception of schc>nie 27 MUNICIPALITIES FOREST !tOAD hiPHOVK\U<JN1' Fl!~ll- c\llocation and cxpendihH'<' 27 ])ECI•;NTK\ LIZA'l'ION Piviaional organization ~--1 'rugi·e;;s 27 RoAr> ~IAKINO .!\'lA'rERIALS--· Aetion by Divisions to ensure supplies 29 TEN·YEAR TARGET- Survey,.; of roatl defieienciP>' and IJPPdR 29 PATROL 0RGAXIZATION HO C 0 N TENTS-continued.