Introduction: Devotion to and Worship in Jerusalem's Temple

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hebrew Roots Movement: an Awakening! History, Beliefs, Apologetics, Criticisms, Issues Fourth Edition 4.04 6/20/20

Preface 1 Preface The Hebrew Roots Movement: An Awakening! History, Beliefs, Apologetics, Criticisms, Issues Fourth Edition 4.04 6/20/20 by Michael G. Bacon Copyright © 2011-2020 All Rights Reserved Pursuant to 17 U.S. Code § 107, certain uses of copyrighted material "for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright." Under the 'fair use' rule of copyright law, an author may make limited use of another author's work without asking permission. Fair use is based on the belief that the public is entitled to freely use portions of copyrighted materials for purposes of commentary and criticism. The fair use privilege is perhaps the most significant limitation on a copyright owner's exclusive rights. The public domain version of the King James Version, published in 1769 and available for free on the E-Sword® Bible Computer Program, is primarily utilized with some contemporary word updates of my own: e.g. thou=you, saith=say, LORD=YHVH. This is a FREE Book It is NOT to be Sold And as ye go, preach, saying, The kingdom of heaven is at hand. Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils: freely ye have received, freely give. —Jesus the Christ / Yeshua haMashiach (Matthew 10:7-8) Important Note: Please refer to http://www.ourfathersfestival.net/hebrew_roots_movement for the latest edition. There are old editions of this book still circulating on the internet. 2 Preface 4.04 June 10, 2020 1906 Jewish Encyclopedia: (Added Anglo-Israelism article quote). -

The Hidden Manna

Outline of the Messages for the Full-time Training in the Spring Term of 2012 ------------------------------------------- GENERAL SUBJECT: EXPERIENCING, ENJOYING, AND EXPRESSING CHRIST Message Fifty-Five In Revelation (4) The Hidden Manna Scripture Reading: Rev. 2:17; Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34 I. The hidden manna mentioned in Revelation 2:17 was hidden in a golden pot in the Ark within the Holy of Holies—Heb. 9:4; Exo. 16:32-34: A. Placing the hidden manna in the golden pot signifies that the hidden Christ is con- cealed in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Col. 3:1, 3; 2 Pet. 1:4. B. The hidden manna is for those who are intimate with the Lord, those who have forsaken the world and every separation between them and God; they come into the intimacy of God’s presence, and here in this divine intimacy they enjoy the hidden manna in the divine nature—Heb. 9:4; Rev. 2:17. C. Our experience of Christ should not merely be open but also hidden in the Holy of Holies, even in Christ Himself as the Ark, the testimony of God—Heb. 10:19: 1. The golden pot is in the Ark, the Ark is in the Holy of Holies, and the Holy of Holies is joined to our spirit; if we continually touch Christ in our spirit, we will enjoy Him as the hidden manna—4:16; 1 Cor. 6:17. 2. The hidden manna is for the person who remains in the innermost part of God’s dwelling place, abiding in the presence of God in the spirit—2 Tim. -

Teshuvah: Being Your Best Self!

TESHUVAH: BEING YOUR BEST SELF! During the days leading up to and including Rosh Hashanah, we spend a lot of time in shul asking Hashem for forgiveness for things we may have done wrong over the course of the year, and we ask for a successful year, a healthy year, and a peaceful year. Also, we are encouraged to reach out to people who maybe we have not spoken to in a while or people we may have had disagreements with and make amends. We can all think to ourselves and make a list of people who might appreciate a phone call, or might be excited to get a text, or wants to become friends again. The months of Elul and Tishrei which contain Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, focus specifically on the middot and character traits of repentance, charity, and prayer. So let’s explore how we can include this attribute of Teshuvah (Repentance) this Rosh Hashanah season, and why it is so important! Teshuvah) which is translated as Repentance) -תְּׁשּובָה This is the act of us righting a wrong, big or small, and it can take place whether it’s between you and a friend, or you and Hashem! During the days leading up to Rosh Hashanah, it is a special time for us to ask for forgiveness and work on ourselves. WHAT ARE 3 THINGS I CAN WORK ON? (It can be something as small as trying to say good things about other people or letting your younger sibling pick what TV show to watch). Fill in below: ____________________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________________ -

From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’S Iconic Texts

Syracuse University SURFACE Religion College of Arts and Sciences 2014 From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/rel Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, History of Religions of Western Origin Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation James W. Watts, "From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts," pre- publication draft, published on SURFACE, Syracuse University Libraries, 2014. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religion by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Ark of the Covenant to Torah Scroll: Ritualizing Israel’s Iconic Texts James W. Watts [Pre-print version of chapter in Ritual Innovation in the Hebrew Bible and Early Judaism (ed. Nathan MacDonald; BZAW 468; Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), 21–34.] The builders of Jerusalem’s Second Temple made a remarkable ritual innovation. They left the Holy of Holies empty, if sources from the end of the Second Temple period are to be believed.1 They apparently rebuilt the other furniture of the temple, but did not remake the ark of the cove- nant that, according to tradition, had occupied the inner sanctum of Israel’s desert Tabernacle and of Solomon’s temple. The fact that the ark of the covenant went missing has excited speculation ever since. It is not my intention to pursue that further here.2 Instead, I want to consider how biblical literature dealt with this ritual innovation. -

“The Challenge of Change”

“The Challenge of Change” a sermon by Dr. William P. Wood First Presbyterian Church Charlotte, North Carolina December 31, 2006 Text: “…in those days, says the Lord, they shall no longer say, ‘The ark of the covenant of the Lord.’ It shall not come to mind, or be remembered, or missed; nor shall another one be made” (Jeremiah 3:16). This morning I want to hold before you two texts taken from the Old Testament. Both have to do with one of the most venerable institutions in ancient Israel: the Ark of the Covenant. The first text is from the book of Joshua, where we read, “Joshua rent his clothes, and fell to the earth upon his face before the ark of the Lord until evening” (Joshua 7:6). The Ark of the Covenant was a sacred ark that Moses had made of wood. It contained the tables of the law (The Ten Commandments). The Ark of the Covenant symbolized the presence of God. It was often taken into battle with the people of Israel as a way of guaranteeing the presence of God in the midst of trouble. When King David was the ruler of Israel, he brought the Ark of the Covenant to Jerusalem. When King Solomon built his magnificent temple in Jerusalem, he placed the Ark of the Covenant in the center. It was the “holy of holies.” It symbolized the presence of God in the holy city. The second text is taken from the prophecy of Jeremiah. By this time 600 years had passed. Speaking of the Ark of the Covenant, Jeremiah had this to say: “In those days, says the Lord, they shall no more say, ‘The Ark of the Covenant of the Lord.’ It shall not come to mind, or be remembered, or missed; it shall not be made again” (Jeremiah 3:16). -

Lesson Four Joshua 3:1-17 Israel Crosses the River Jordan Key Concept: the LORD Is with Those Who Follow Him

Lesson Four Joshua 3:1-17 Israel crosses the River Jordan Key Concept: The LORD is with those who follow Him. Key Verse: Behold, the ark of the covenant of the LORD of all the earth is crossing over ahead of you into the Jordan. (Joshua 3:11) The Before Word: As Joshua and the Israelites are poised to cross the Jordan River and enter the land promised to their forefathers, GOD wants them to know that He is traveling with them. As you study Joshua 3, look for all the ways GOD shows the people that He is with them and all the ways He shows Joshua that He is with him. As you work through the scripture, record all the ways the LORD assured Joshua and the people that He was with them as they crossed over. This exercise is designed to increase your faith and your ability to see all the ways the LORD is traveling with you! Record all the ways the LORD assured the people and Joshua that He was with them as they crossed over the river. (Record the verse along with the assurance.) Assurances to the People Scripture Assurances to Joshua Scripture Questions for Joshua 3 1. 1. a. Where were the Israelites positioned? (3:1-2) b. For how long did they wait? 1. 2. a. Who was to lead the Israelites across the Jordan River? (3:3-4) b. What were they to carry? c. Why did the officers warn them to keep a distance of 2,000 cubits? d. What significance do you see in this arrangement? The Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:10-22) was constructed of acacia wood, overlaid with gold, covered with golden cherubim, and housed three articles: Aaron’s Rod of Budding, The Stone Tablets of the Law, and a Jar of Manna. -

Herod's Temple Depositories Were Located Near the Temple Treasury; the Contents of Door, They Should Throw Him out As Well

33 32 15 34 35 31 30 29 16 53 58 17 3 1 37 21 36 5 50 48 22 56 55 28 10 51 46 45 43 42 23 14 8 9 6 7 12 47 44 52 11 55 41 40 27 36 49 57 57 2 37 26 24 20 19 18 58 4 39 38 25 54 13 © 1. The Chamber or Court of Wood -According to the Mishnah, 7. The Beautiful Gate - This Gate led into the Court of Women, where by 2001, there were four unroofed chambers in the four corners of the Court all Jews could enter, except the ritually impure, and ironically of Women. The North-East corner was the place where unclean ‘women’. It was the principal entrance to the Temple. Unlike the priests inspected the firewood to be used in the Temple. They other gates, overlaid with silver and gold, the doors of this Gate were Martin Allen Hansen Allen Martin served by removing wood that was worm-eaten or rotten. made of Corinthian brass, so heavy it took 20 men to open them. 2. The Chamber or Court of the Nazarene – In the South-East 8. Nicanor’s Gate - The Court of Women led into the main court of the corner of the Court of Women was a room where those taking the Temple, known as ‘Azarah’, via a semicirclular stairway of 15 steps, Nazarite vow would cut their hair and cook their peace-offerings. which led up to the Nicanor or Upper gate. According to Josephus, 3. -

Exclusion from the Sanctuary and the City of the Sanctuary in the Temple Scroll

EXCLUSION FROM THE SANCTUARY AND THE CITY OF THE SANCTUARY IN THE TEMPLE SCROLL by LA WREN CE H. SCHIFFMAN New York University, New York, N. Y. 10012 Introduction The discovery and publication of the Temple Scroll (Yadin, 1977, 1983; abbreviated below as 11 QT) opened new vistas for the study of the history of Jewish law in the Second Commonwealth period. Immedi ately after the Hebrew edition of the scroll appeared, debate ensued about whether this scroll was to be seen as an integral part of the corpus authored by the Qumran sect, or simply as a part of its library (cf. Schiffman, 1983a, 1985c). This question was, in turn, related to the problem of whether this text reflects generally held beliefs of most Second Temple Jews, or whether its laws and sacrificial procedures represented only the views of its author(s), who were demanding a thor oughgoing revision of the sacrificial worship of the Jerusalem Temple, or, finally, whether it reflected the author's eschatological hopes. This question is crucial in regard to the laws pertaining to various classes of individuals who were to be excluded from the Temple, its city (known in the Temple Scroll as cir hammiqdiis, "the city of the sanc tuary" or "Temple city") and the other cities of Israel because of various forms of ritual impurity or other disqualifications. The editor of the scroll, Yigael Yadin, maintained that it represented a point of view substantially stricter than that of the somewhat later tannaitic sources, and that the scroll extended all prohibitions of such impurity to the entire city of Jerusalem at least. -

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES in the HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters a Dissertation Submitted to the Johns Hopkins Universit

THRESHING FLOORS AS SACRED SPACES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE by Jaime L. Waters A dissertation submitted to The Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland August 2013 © 2013 Jaime L. Waters All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Vital to an agrarian community’s survival, threshing floors are agricultural spaces where crops are threshed and winnowed. As an agrarian society, ancient Israel used threshing floors to perform these necessary activities of food processing, but the Hebrew Bible includes very few references to these actions happening on threshing floors. Instead, several cultic activities including mourning rites, divination rituals, cultic processions, and sacrifices occur on these agricultural spaces. Moreover, the Solomonic temple was built on a threshing floor. Though seemingly ordinary agricultural spaces, the Hebrew Bible situates a variety of extraordinary cultic activities on these locations. In examining references to threshing floors in the Hebrew Bible, this dissertation will show that these agricultural spaces are also sacred spaces connected to Yahweh. Three chapters will explore different aspects of this connection. Divine control of threshing floors will be demonstrated as Yahweh exhibits power to curse, bless, and save threshing floors from foreign attacks. Accessibility and divine manifestation of Yahweh will be demonstrated in passages that narrate cultic activities on threshing floors. Cultic laws will reveal the links between threshing floors, divine offerings and blessings. One chapter will also address the sociological features of threshing floors with particular attention given to the social actors involved in cultic activities and temple construction. By studying references to threshing floors as a collection, a research project that has not been done previously, the close relationship between threshing floors and the divine will be visible, and a more nuanced understanding of these spaces will be achieved. -

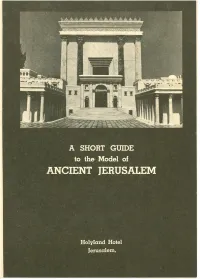

Model of Ancient Jerusalem.Pdf

II The model represents Ancient Jerusalem in 66 C.E. at the beginning of the First Revolt against Rome. '.'..!'[71'l1 Its scale is I: 50 (2 ems. equal one metre, )4: inch - one' 1\ foot). An average man in scale would be 3~ ems. or 12/5 in- The model is reached opposite the tower Psepmnus (1 on ches high. The model has been constructed as far as possible of ~e.I~I~ the plan) the north-western corner tower in the Outer or Third ,~ the original materials used at the time, marble. stone and wood, Wall. copper and iron. Ancient Jerusalem was defended by three such walls on its The sources used in planning the model were the Mishnah, vulnerable northern side, while a single wall was sufficient on the Tosephtha, the Talmuds. Josephus and the New Testament. the west, south and east, because of the deep valleys surround- Psephinus Tower The construction of the model is due to the initiative and ing the city on these sides. The Third Wall was begun by King resources of Mr. Hans Kroch. The archaeological and topogra- Agrippa I (41-44 C.E.) and completed at the beginning of the phical data were supplied by Prof. M. Avi-Yonah, Hebrew Uni- First Revolt against Rome (66 C.E.). Its corner tower, Psephi- versity, Jerusalem, one of the foremost living authorities on the nus, was octagonal in shape. Its original height was 35 m. or subject. Mrs. Eva Avi-Yonah drew the plans, sections and 1]5 feet, which corresponds to 0.70 m. -

Emuna/7/Trustworthiness1

Tikki • Project Currici Draft. February 2014 Emuna/7/TrUStWOrthineSS1 While Emunah is usually translated as faith, in this session we focus on its related meaning - Trustworthiness. Emunah shares a Hebrew root with Oman, an artisan - someone who can be trusted or relied upon to produce a quality product. Emunah is that quality of reliability that we engender in others through our sustained honesty and consideration. A person or institution that acts with Emuno/i/trustworthiness is one in which you can have faith. Emunah as Fundamental to Life -Talmud Bavli Shabbat 31a and Tosafot The prophet lsaiah(33:6) describes some of the positive attributes of the Jewish people as follows: "Faithfulness to Your charge was [her] wealth, wisdom and devotion [her] triumph, reverence for God - that was her treasure." The word used for "Faithfulness" is "Emunah." The rabbis of the Talmud relate each phrase in Isaiah's passage to one of the six sections of the Mishnah, the 3rd century encyclopedia of Jewish law. The word 'faithfulness/EmL/nar?' in the verse refers to the section of Mishnah, "Seeds," that deals with agriculture. (Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 31a) The Tosafot, 13th centuryTalmud commentators, explore the relationship between the term "Emunah" and agriculture: The farmer who sows seeds places his faith in the Lifegiver of All the Worlds, for he trusts that God will provide all that is needed for his crops to grow. Ifthe farmer didn't trust at some level that the seeds would grow in the ground s/he would probably not go to the effort to hoe and plow and do all the work needed to produce crops. -

Taxation in the Bible During the Period of the First and Second Temples, 7 J

UIC School of Law UIC Law Open Access Repository UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1998 Taxation in the Bible during the Period of the First and Second Temples, 7 J. Int'l L. & Prac. 225 (1998) Ronald Z. Domsky John Marshall Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Ronald Z. Domsky, Taxation in the Bible during the Period of the First and Second Temples, 7 J. Int'l L. & Prac. 225 (1998). https://repository.law.uic.edu/facpubs/180 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UIC Law Open Access Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UIC Law Open Access Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of UIC Law Open Access Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAXATION IN THE BIBLE DURING THE PERIOD OF THE FIRST AND SECOND TEMPLES Ronald Z. Domsky* Part I: Period of the First Temple ....................... 228 A. Fiscal Policies of the Kingdom ............... 228 B. Revenue Sources of the Priesthood ............ 236 1. Tax Laws ............................. 236 Part II: Period of the Second Temple .................... 240 A. Governmental Validity/Force for Tax Laws During the Days of Ezra and Nehemia ......... 240 B. Explanation of Tax Laws .................... 244 1. First Fruits ............................ 246 2. Contribution/Offering ................... 247 3. Challa ............................... 247 4. Tenth ................................ 248 5. Support for Those in Need ............... 250 6. Sum mary ............................. 250 C. Smuggling of Taxes and its Prevention ......... 251 D. The Shekel and the Vows ..................