In the Past Few Years, Wal-Mart Has Made Significant Inroads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Meat Conference Attendee List As of 2.21.2018

2018 Annual Meat Conference Attendee List as of 2.21.2018 First Name Last Name Title Company Anne-Marie Roerink Principal 210 Analytics Marc DiPersio Vice President and Director, Fresh Foods A.J. Letizio Sales & Marketing, Inc. Nick Letizio Business Manager A.J. Letizio Sales & Marketing, Inc. Altneik Nesbit Purchasing Agent Abaco Groceries Marsh Harbour Martin McMahon General Manager ABP Food Group Gavin Murphy National Sales Manager ABP North America Jeffery Berlin Vice President, Fresh Foods Acosta Patrick Beyer Vice President, Fresh Acosta Dennis Blackmon Vice President, Food Service Acosta David Dobronski Associate Acosta Chad Judd Senior Business Manager Acosta Chris Korsak Director Acosta Christopher Love Vice President Acosta Rusty Mcdaniel Vice President, Fresh Foods Acosta Karen Olson Vice President, Fresh Foods Acosta Rick Pike Manager, Key Accounts Acosta Cliff Richardson Associate Acosta Ernie Vespole Senior Vice President, Fresh Foods Grocery Sales East Region Acosta Preston Harrell Sales Executive Action Food Sales, Inc. Mike Hughes Account Executive Action Food Sales, Inc. Mike Mickie Account Executive Action Food Sales, Inc. John Nilsson Vice President of Sales & Operations Action Food Sales, Inc. John Nilsson President Action Food Sales, Inc. Nikki Bauer Sales, Arizona Advanced Marketing Concepts Bill Claflin Sales Advanced Marketing Concepts Jim Baird Sales Manager Advantage Solutions Victor Bontomasi Director, Sales Advantage Solutions Bill Brader Area Vice President Advantage Solutions Mark Clausen Area Vice President -

Pharmacies Located in North Carolina

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina Limited Network: Pharmacies Located in North Carolina Pharmacy Name Address City State Zip Phone Number 1ST RX PHARMACY 837 N CENTER ST STATESVILLE NC 28677 7048720880 1ST RX PHARMACY INC- GREENBRIAR 308-A MOCKSVILLE HWY STATESVILLE NC 28625 7048786225 A1 PHARMACY AND SURGICAL SUPPLY LLC 124 FOREST HILL RD LEXINGTON NC 27295 3362246500 A2Z HEALTHMART PHARMACY 1408 ARCHDALE DR CHARLOTTE NC 28210 9803550906 ABERDEEN PRESCRIPTION SHOPPE 1389 N SANDHILLS BLVD ABERDEEN NC 28315 9109441313 ADDICTION RECOVERY MEDICAL SERVICES 536 SIGNAL HILL DRIVE EXT STATESVILLE NC 28625 7048181117 ADULT CLINIC AND GERIATRIC CENTER A 25 OFFICE PARK DRIVE JACKSONVILLE NC 28546 9103534878 ADVANCED HOME CARE 4001 PIEDMONT PKWY GREENSBORO NC 27265 3368788950 AKERS PHARMACY INC 1595 E GARRISON BLVD GASTONIA NC 28054 7048653411 ALBEMARLE COMPNDN N PRESCRIPT CNT 944 N FIRST ST ALBEMARLE NC 28001 7049836176 ALBEMARLE PHARMACY 105 YADKIN ST ALBEMARLE NC 28001 7049838222 ALLCARE PHARMACY SERVICES, LLC 5176 NC HIGHWAY 42 W STE H GARNER NC 27529 9199267371 ALLEN DRUG 220 S MAIN ST STANLEY NC 28164 7042634876 ALLEN DRUGS INC 9026 HIGHWAY 17 POLLOCKSVILLE NC 28573 2522245591 ALMANDS DRUG STORE 3621 SUNSET AVE ROCKY MOUNT NC 27804 2524433138 ANDERSON CREEK PHARMACY, INC 6779 OVERHILLS RD SPRING LAKE NC 28390 9104976337 ANGIER DISCOUNT DRUG 253 N RALIEGH STREET ANGIER NC 27501 9196399623 ANSON PHARMACY INC 806 CAMDEN RD WADESBORO NC 28170 7046949358 APEX PHARMACY 904 W WILLIAMS ST APEX NC 27502 9196297146 ARCHDALE DRUG AT CORNERSTONE -

United Natural Foods (UNFI)

United Natural Foods Annual Report 2019 Form 10-K (NYSE:UNFI) Published: October 1st, 2019 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended August 3, 2019 or ¨ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from _______ to _______ Commission File Number: 001-15723 UNITED NATURAL FOODS, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 05-0376157 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 313 Iron Horse Way, Providence, RI 02908 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (401) 528-8634 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange on which Title of each class Trading Symbol registered Common Stock, par value $0.01 per share UNFI New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ¨ No x Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

November 29Th, 2020 Sprouts Farmers Market, Inc. Is a Food

SPROUTS FARMERS MARKET, INC. RECOMMENDATION: BUY November 29th, 2020 Ticker: SFM (NASD) Sprouts Farmers Market, Inc. is a food retailer Market Price: $20.59 operating in the United States with 341 stores across Price Target: $29.38 22 states, primarily in the south-west, a majority of which are located in California, Texas, Colorado and Upside: 43% Arizona. Sprouts focuses on offering a range of 52w Range: $13.00 - 28.00 natural & organic food, differentiating themselves from their competition. EPS (2019): 1.25 PERFORMANCE HISTORY INVESTMENT SUMMARY: • Sprouts have seen strong growth since their IPO 50 in 2013, boasting a 5-year revenue CAGR of 40 9.42% and healthy cash flows. 30 • Sprouts maintain a price advantage over their closest competitors Whole Foods. 20 • Maintenance of healthy net margins by 10 comparison to the industry as a whole. 0 • Furthermore, there is additional upside potential 2013 2020 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 should Sprouts exceed store growth expectations 2014 which we have set to a conservative rate of 24 additional stores per year over the next 5 years, COMPANY INFORMATION giving a 5-year CAGR of 5.46%, well above the forecasted industry 5-year CAGR of 1.7%. Revenue (2019): $5,635m Employees: 30,000 Fiscal Year End: December Headquarters: Arizona www.sprouts.com Matthew Keane [email protected] Miah Rohan [email protected] GROWTH Sprouts Farmers Market made their Initial Public Offering in 2013, thus providing 7 years’ worth of store growth data (figure 1), we can observe that sprouts store growth has been declining steadily since 2013. -

Tobacco Retail ID Estab Name Location Street 1 HEATH's EAST

tobacco_retail ID Estab Name Location Street 1 HEATH'S EAST VILLAGE VARIETY ROUTE 5/202 & 4 2 KIM'S MARKET 59 MEDWAY ROAD 3 TOZIER'S MARKET 483 SOUTH MAIN STREET 4 SWANS ISLAND GENERAL STORE 127 MINTURN ROAD 5 CARATUNK GENERAL STORE MAIN STREET 6 PARENT'S COUNTRY STORE IN VAN BUREN ROAD 7 U.M.P.I. BOOKSTORE - P.I. 181 MAIN STREET 8 GOWELL'S MARKET 121 HAMPSHIRE STREET 9 FOOD PLAZA CONVENIENCE UNIT 6,29 WESTERN AVENUE 10 TRETT'S MAIN STREET 11 NORTH COUNTRY VARIETY LOWER MAIN STREET 16 HABEEB'S SMOKE SHOP 82 HERSCHEL STREET 17 HOWLAND FAMILY GROCERY 38 MAIN STREET 18 POP'S PIZZA 23 MAIN STREET 21 ROGER'S MARKET CORNER RT. 221 & 43 22 WILSON'S DRUG STORE INC. 114 FRONT STREET 25 HUBER'S MARKET BATH ROAD (ROUTE 1) 26 HUSSEY'S GENERAL STORE CORNER OF RTE 32 & 105 27 SMYRNA MILLS VARIETY ROUTE 2 29 YELLOW FRONT GROCERY INC UPPER MAIN STREET 30 SOMERSET COUNTY CORRECTIONAL COURT STREET 32 SAYER'S VARIETY STORE 833 GRAY ROAD 33 OCEAN ST. MARKET BASKET 460 OCEAN STREET 34 CORNER VARIETY 207 LINCOLN STREET 36 VILLAGE GENERAL STORE ROUTE 194 37 A.Z.'S FRESH FOOD 20 HEATH STREET 38 THREE SIXTY MGM. SERVICE 1332 MAIN STREET 39 NUTTER'S CASH MARKET BRIDGE STREET 40 RIVERSIDE MARKET CORP. ROUTE 201A 43 OLAMON MARKET MILITARY ROAD 44 SNOW'S A.G. 101 SOUTH STAGECOACH ROAD 45 DESMOND'S VARIETY INC ROUTE 15 ELM STREET 46 JOE'S SMOKE SHOP 123 MAIN STREET 47 ASHLAND ONE STOP 117 MAIN STREET 48 NORTHEND VARIETY STORE 40 TICONIC STREET 49 JIM'S CONVENIENCE PLUS U.S. -

Moderna Vaccine Allocation (Non-LTCF)

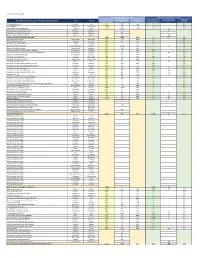

Data as of February 17, 2021 Staff Entry: A Aul 0845, DH 0930 Moderna FIRST Doses (non-LTCF) Moderna SECOND Doses (non-LTCF) Total FIRST Doses Utilization Total SECOND Doses DHEC Moderna Direct Ship Vaccine Providers/Ordering Facilities City County Total Administered Total Administered Utilization Received-Note 3 Note 1 Note 2 Received-Note 3 Note 1 Note 2 Affinity Health Center Rock Hill York 300 297 99% 0 0% Agape (Note 4) Spartanburg Spartanburg 1,300 225 17% 0 0% Aiken County Health Department Aiken Aiken 1,500 1,733 116% 0 101 0% Anderson County Health Department Anderson Anderson 1,978 569 Abbeville County Health Department Abbeville Abbeville 304 Pickens County Health Department Pickens Pickens 226 103 Anderson County HD/Upstate Group Total 1,900 2,508 132% 0 672 0% Angel Oak Family Practice Johns Island Charleston 200 258 129% 0 0% Barnwell Health Department Barnwell Barnwell 200 124 62% 0 0% Brookland Cayce Medical Practice Cayce Lexington 200 0 0% 0 0% Burke's Main Street Pharmacy Hilton Head Island Beaufort 3,300 1,978 60% 0 4 0% Calhoun Falls Family Practice Calhoun Falls Abbeville 600 200 33% 0 0% CareSouth Carolina-Bennettsville Main (135052) Bennettsville Marlboro 300 119 40% 200 0% CareSouth Carolina-Bennettsville Pediatrics (135106) (Note 4) Bennettsville Marlboro 300 10 3% 0 10 0% CareSouth Carolina-Bishop Main Bennettsville Marlboro 400 543 136% 0 0% CareSouth Carolina-Cheraw Cheraw Chesterfield 300 90 30% 200 20 10% CareSouth Carolina-Chesterfield Chesterfield Chesterfield 900 986 110% 0 0% CareSouth Carolina-Dillon Dillon Dillon 500 10 2% 0 10 0% CareSouth Carolina-Hartsville Medical (116109) Hartsville Hartsville 300 239 80% 200 0% CareSouth Carolina-Hartsville Pediatrics (116050) Hartsville Hartsville 300 214 71% 200 0% CareSouth Carolina-Latta Center Latta Dillon 600 833 139% 0 27 0% CareSouth Carolina-McColl (Note 4) McColl Marlboro 1,000 974 97% 200 18 9% CareSouth Carolina-S. -

Alabama Vendor List.Xlsx

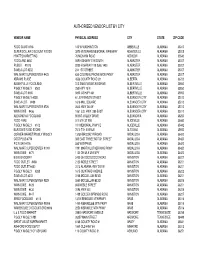

AUTHORIZED VENDOR LIST BY CITY VENDOR NAME PHYSICAL ADDRESS CITY STATE ZIP CODE FOOD GIANT #716 100 W WASHINGTON ABBEVILLE ALABAMA 36310 SUPER DOLLAR DISCOUNT FOODS 3970 VETERANS MEMORIAL PARKWAY ADAMSVILLE ALABAMA 35005 HYATT'S MARKET INC 70 MCHANN ROAD ADDISON ALABAMA 35540 FOODLAND #450 509 HIGHWAY 119 SOUTH ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 PUBLIX #1073 9200 HIGHWAY 119 Suite 1400 ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 SAVE-A-LOT #202 244 1ST STREET ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #423 630 COLONIAL PROMENADE PKWY ALABASTER ALABAMA 35007 ABRAMS PLACE 4556 COUNTY ROAD 29 ALBERTA ALABAMA 36720 ALBERTVILLE FOODLAND 313 SAND MOUNTAIN DRIVE ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #500 250 HWY 75 N ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 SAVE-A-LOT #165 5850 US HWY 431 ALBERTVILLE ALABAMA 35950 PIGGLY WIGGLY #238 61 JEFFERSON STREET ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 SAVE-A-LOT #489 1616 MILL SQUARE ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #726 2643 HWY 280 W ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 WINN DIXIE #456 1061 U.S. HWY. 280 EAST ALEXANDER CITY ALABAMA 35010 ALEXANDRIA FOODLAND 85 BIG VALLEY DRIVE ALEXANDRIA ALABAMA 36250 FOOD FARE 517 5TH ST NW ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 PIGGLY WIGGLY #102 101 MEMORIAL PKWY E ALICEVILLE ALABAMA 35442 BURTON'S FOOD STORE 7010 7TH AVENUE ALTOONA ALABAMA 35952 CORNER MARKET/PIGGLY WIGGLY 13759 BROOKLYN ROAD ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 COST PLUS #774 305 EAST THREE NOTCH STREET ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 PIC N SAV #776 550 W BYPASS ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WAL MART SUPERCENTER #1091 1991 MARTIN LUTHER KING PKWY ANDALUSIA ALABAMA 36420 WINN DIXIE -

Pharmacy Network Chains and Psaos1

Broad Pharmacy Network Chains and PSAOs1 The OptumRx national network has more than 67,000 retail pharmacy sites across the country including Puerto Rico, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. There’s usually a pharmacy nearby with this large network. Some sites meet Pharmacy Service Administration Organization (PSAO) standards to help promote generic use, which may lower costs. A Complete Claims Processing H AADP Cook County H.E.B. Pharmacy Access Health Coram LLC Hannaford – Ahold Accredo Health Costco Harris Teeter – Kroger AHS St. John Pharmacy Cresent Health Care Harvard Vanguard Ahold/Delahaize CVS Pharmacy Health Mart Atlas Albertsons D Home Choice Partners American Drug – Albertsons Dallas Metrocare Services Hy-Vee American Pharmacy Denver Health & Hospital I Amerita Inc. Dillon – Kroger IHS Pharmacy Services Amerisource Diplomat Indian Health Service Arete/United Discount Drug Mart – Cardinal Infusion Partners Aurora Pharmacy DMVA Pharmacies Ingles Markets B Doctors Choice Innovatix Network Balls Four B E Inserra – Shoprite Supermarkets Bartell Drugs Eaton INSTYMEDS Baystate Medical Center Elevate Provider J Bemidji Area IHS Epic Pharmacy JPS Health System Bi Lo – Winn Dixie F K BioRx F&F Pharmacies King Soopers – Kroger Brookshire Fairview Health Kinney Drugs Brookshire Brothers Fairview Pharmacy Klein’s Family – Shoprite C Food Lion – Hannaford Supermarkets Cardinal Health Fred Meyer – Kroger Klingensmiths Drug Store Caremark Fred’s – Cardinal Kholls Pharmacy and Homecare Carrs – Albertsons Fruth – Cardinal K-mart Central Dakota -

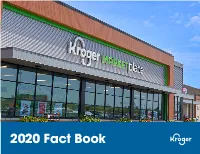

2020 Fact Book Kroger at a Glance KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 2 Pick up and Delivery Available to 97% of Custom- Ers

2020 Fact Book Kroger At A Glance KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 2 Pick up and Delivery available to 97% of Custom- ers PICK UP AND DELIVERY 2,255 AVAILABLE TO PHARMACIES $132.5B AND ALMOST TOTAL 2020 SALES 271 MILLION 98% PRESCRIPTIONS FILLED HOUSEHOLDS 31 OF NEARLY WE COVER 45 500,000 640 ASSOCIATES MILLION DISTRIBUTION COMPANY-WIDE CENTERS MEALS 34 DONATED THROUGH 100 FEEDING AMERICA FOOD FOOD BANK PARTNERS PRODUCTION PLANTS ARE 35 STATES ACHIEVED 2,223 ZERO WASTE & THE DISTRICT PICK UP 81% 1,596 LOCATIONS WASTE OF COLUMBIA SUPERMARKET DIVERSION FUEL CENTERS FROM LANDFILLS COMPANY WIDE 90 MILLION POUNDS OF FOOD 2,742 RESCUED SUPERMARKETS & 2.3 MULTI-DEPARTMENT STORES BILLION kWh ONE OF AMERICA’S 9MCUSTOMERS $213M AVOIDED SINCE MOST RESPONSIBLE TO END HUNGER 2000 DAILY IN OUR COMMUNITIES COMPANIES OF 2021 AS RECOGNIZED BY NEWSWEEK KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 Table of Contents About 1 Overview 2 Letter to Shareholders 4 Restock Kroger and Our Priorities 10 Redefine Customer Expereince 11 Partner for Customer Value 26 Develop Talent 34 Live Our Purpose 39 Create Shareholder Value 42 Appendix 51 KROGER FACT BOOK 2020 ABOUT THE KROGER FACT BOOK This Fact Book provides certain financial and adjusted free cash flow goals may be affected changes in inflation or deflation in product and operating information about The Kroger Co. by: COVID-19 pandemic related factors, risks operating costs; stock repurchases; Kroger’s (Kroger®) and its consolidated subsidiaries. It is and challenges, including among others, the ability to retain pharmacy sales from third party intended to provide general information about length of time that the pandemic continues, payors; consolidation in the healthcare industry, Kroger and therefore does not include the new variants of the virus, the effect of the including pharmacy benefit managers; Kroger’s Company’s consolidated financial statements easing of restrictions, lack of access to vaccines ability to negotiate modifications to multi- and notes. -

Market Structure Analysis of Florida Metropolitan and Micropolitan

Retail Grocery Market Structure Analysis of Virginia Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas Prepared for Virginia Community Capital (VCC) by The Reinvestment Fund (TRF) as part of the ReFresh initiative, supported by JPMorgan Chase | February 2015 Retail Grocery Market Structure Analysis of Virginia Metropolitan and Micropolitan Areas Prepared for Virginia Community Capital (VCC) by The Reinvestment Fund (TRF) as part of the ReFresh initiative, supported by JPMorgan Chase | February 2015 TRF’s Market Structure Analysis measures the concentration of market share within a region’s retail grocery industry. In general, as the concentration of market share within the top few grocers increases, the region’s overall level of competition within the industry decreases as it evolves into a tighter oligopoly.1 An oligopoly is a market condition in which the supply of a good or service is largely controlled by a small number of entities, each of which is in a position to influence prices, thus directly affecting its competitors’ ability to sustain profitability. After decades of mergers, acquisitions, and emphasis on economies of scale, the retail grocery industry has naturally evolved into an oligopoly, ranging in intensity from tight (fewer majority owners) to loose (more majority owners), based on the number of owning entities controlling the majority market share.2 TRF’s experience with the Pennsylvania Fresh Food Financing Initiative suggests that a tight oligopoly in at least one Pennsylvania metro area made market penetration especially difficult for local and regional grocers that were not members of the oligopoly. Conversely, loose oligopolies with less concentrated market share exhibited fewer barriers to entry for prospective grocers. -

Usc Card Statement - Team Travel January 2021

USC CARD STATEMENT - TEAM TRAVEL JANUARY 2021 CARDHOLDER MERCHANT DATE AMOUNT Assaley,Andrew L CRACKER BARREL #152 BATON 1/18/2021 359.48 DRAGOS SEAFOOD RESTAUR 1/18/2021 801.30 OLIVE GARDEN 0021599 1/18/2021 759.97 SMOOTHIE KING - 1911 - BA 1/18/2021 181.33 TST* ATOMIC BURGER - BATO 1/18/2021 306.96 WALK ONS BISTREAUX AND BA 1/18/2021 540.45 STADIUM GRILL 1/20/2021 427.12 DOUBLETREE HOTEL COLUMBI 1/22/2021 3,789.03 DOUBLETREE HOTEL COLUMBI 1/22/2021 5,974.81 RENAISSANCE BATON ROUG 1/25/2021 3,718.88 16,859.33 Burke,Rebecca China Olive 12/28/2020 31.67 DOMINO'S 5637 12/28/2020 84.88 INGLES MARKETS #204 12/28/2020 67.12 INGLES MARKETS #45 12/28/2020 131.55 FOOD LION #2641 12/29/2020 50.13 INGLES MARKETS #38 12/30/2020 105.89 MCDONALD'S F5193 12/31/2020 26.16 BIG LOTS #5360 1/4/2021 22.47 DOMINO'S 5648 1/4/2021 43.26 FOOD LION #2641 1/4/2021 28.56 INGLES MARKETS #202 1/4/2021 56.08 PINOS ITALIAN RESTAURANT 1/4/2021 103.60 CHARLEY`S WATERFRONT CAFE 1/5/2021 120.00 PIZZA WORLD FARMVILLE 2 1/5/2021 120.38 DOMINO'S 4275 1/6/2021 64.03 Subway 5020 1/6/2021 108.87 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 HAMPTON INN FARMVILLE 1/7/2021 199.90 PINOS ITALIAN RESTAURANT 1/7/2021 8.93 PINOS ITALIAN RESTAURANT 1/7/2021 10.39 PINOS ITALIAN RESTAURANT 1/7/2021 134.42 INGLES MARKETS #45 1/11/2021 7.49 DOLLAR TREE 1/12/2021 30.98 QT -

Kroger and Roundy's to Merge in $800 Million Deal

- Advertisement - Kroger and Roundy’s to merge in $800 million deal November 11, 2015 Supermarket operator Kroger Co., based in Cincinnati, will purchase all outstanding shares of Milwaukee-based retailer Roundy’s in a merger deal valued at $800 million that was announced Nov. 11. The $3.60 per share that Kroger will pay represents a 65 percent premium over the per-share price of Roundy’s stock at the close of trading Nov. 10. Roundy’s will operate as a subsidiary of the Kroger Co. and will be led by current members of Roundy’s senior management. Its headquarters will remain in Milwaukee. 1 / 2 "We are delighted to welcome Roundy's to the Kroger family," Rodney McMullen, Kroger's chairman and chief executive officer, said in a Nov. 11 press release. "With a team of 22,000 talented associates, outstanding store locations, and a shared commitment to putting customers first, we are excited about Roundy's future growth.” “We are excited about becoming part of The Kroger Co.,” Robert A. Mariano, chairman of the board, president and chief executive officer of Roundy’s Inc., said in the press release. “Kroger’s scale, knowledge and experience allows us to accelerate the strategic initiatives we have invested in and makes us a more formidable competitor in the marketplace. This is a great win for our customers, communities, employees and our shareholders, and I personally look forward to continue to exceed customer and employee expectations.” Combined, Kroger and Roundy’s will operate 2,774 supermarkets and employ over 422,000 associates across 35 states and the District of Columbia.