Intricacies of Chennai Metropolitan Water Laws 1. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study (CCTS)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The consultants are grateful to Tmt. Susan Mathew, I.A.S., Addl. Chief Secretary to Govt. & Vice-Chairperson, CMDA and Thiru Dayanand Kataria, I.A.S., Member - Secretary, CMDA for the valuable support and encouragement extended to the Study. Our thanks are also due to the former Vice-Chairman, Thiru T.R. Srinivasan, I.A.S., (Retd.) and former Member-Secretary Thiru Md. Nasimuddin, I.A.S. for having given an opportunity to undertake the Chennai Comprehensive Transportation Study. The consultants also thank Thiru.Vikram Kapur, I.A.S. for the guidance and encouragement given in taking the Study forward. We place our record of sincere gratitude to the Project Management Unit of TNUDP-III in CMDA, comprising Thiru K. Kumar, Chief Planner, Thiru M. Sivashanmugam, Senior Planner, & Tmt. R. Meena, Assistant Planner for their unstinted and valuable contribution throughout the assignment. We thank Thiru C. Palanivelu, Member-Chief Planner for the guidance and support extended. The comments and suggestions of the World Bank on the stage reports are duly acknowledged. The consultants are thankful to the Steering Committee comprising the Secretaries to Govt., and Heads of Departments concerned with urban transport, chaired by Vice- Chairperson, CMDA and the Technical Committee chaired by the Chief Planner, CMDA and represented by Department of Highways, Southern Railways, Metropolitan Transport Corporation, Chennai Municipal Corporation, Chennai Port Trust, Chennai Traffic Police, Chennai Sub-urban Police, Commissionerate of Municipal Administration, IIT-Madras and the representatives of NGOs. The consultants place on record the support and cooperation extended by the officers and staff of CMDA and various project implementing organizations and the residents of Chennai, without whom the study would not have been successful. -

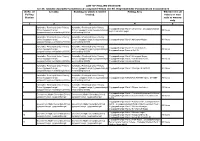

LIST of POLLING STATIONS for 28. Alandur Assembly Constituency Comprised Within the 05

LIST OF POLLING STATIONS for 28. Alandur Assembly Constituency comprised within the 05. Sriperumbudur Parliamentary Constituency Sl No. of Locality Building in which it will be Polling Area Whether for all Polling located voters or men Station only or women only 1 2 3 4 5 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary 1.Iyyappanthangal Ward 1 union salai , 2.Iyyappanthangal 1 School Iyyappanthangal, School Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal All Voters Ward 2 kamatchi nagar Iyyappanthangal west building 600056. west building 600056. Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary 2 School Iyyappanthangal, School Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 1.Iyyappanthangal Ward 1 Athithanar Nagar All Voters Iyyappanthangal west building 600056. west building 600056. Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary 1.Iyyappanthangal Ward 1 Perumal Koil St , 3 School Iyyappanthangal, School Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal All Voters 2.Iyyappanthangal Perumal Koil St Iyyappanthangal west building 600056. west building 600056. Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary 1.Iyyappanthangal Ward 1 Venugopal Nagar , 4 School Iyyappanthangal, School Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 2.Iyyappanthangal Ward 2 mariamman koil st , All Voters Iyyappanthangal west building 600056. west building 600056. 3.Iyyappanthangal Venugopal Nagar Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary 5 School Iyyappanthangal, School Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 1.Iyyappanthangal -

Commprehen Drainage Nsive Scien E Systems Ntific Stud S Inside a Dy To

Comprehensive scientific study to suggest improvements to the drainage systems inside and outside the Airport premises Final Report by Balaji Narasimhan, Soumendra Nath Kuiry and K. P. Sudheer DEPARTMENT OF CIVIL ENGINEERING INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MADRAS. August 2017 Work Order: AAM/ENGG/901/B/CMD‐I/2016/890 dated 06/07/2016 Original Agreement No: 02/CMD‐I/2016‐17 Acknowledgements We would like to acknowledge the help and unflinching support extended by Mr.A. A. Michael Raj, Joint General Manager(ENGG‐CIVIL)‐I, and Mr. I.Palanichamy, Asst.General Manager (E‐C) ‐ II, Civil Maintenance Division. Their commitment, involvement, and continuous follow‐up with regulatory bodies to get the necessary clearances ensured smooth collection of field data and survey with UAS. Surveying with UAS in the airport operational area and in the vicinity carried out as part of this study, to develop a high resolution digital elevation model for flood modelling, is a first of its kind in the country. It involves meticulous planning and a choreographed operation of several departments in the airport. The investigators would like to place on record their sincere appreciation to Mr. Sylvester Israel, GM (ATM‐CH) who led a large team of dedicated staff, each entrusted with a specific responsibility to ensure smooth, glitch free operation of the survey. In particular, the contribution of Mr. N. Nagarajan, Rtd. JGM (ATM), Consultant in coordinating the ground operation of UAS and Mr. R. Sridhar Jt. GM (ATM) at the air traffic control are significant. We would like to thank the then Airport Director, Mr. -

Kancheepuram District Map N

KANCHEEPURAM DISTRICT MAP N W E TIRUVALLUR DISTRICT S THIRUVALLUR KONDAVAKKAM CHENNAI AYYAPANTHANGAL CHENNAI KANDAMANGALAM CHENNAI THELLIARAGARAM MEVALURCUPPAM SRINIVASAPURAM DISTRICT MANGADU T.P KOLATHUVANJERI NANDAMBAKKKAM SENGADU CHENNAI MANNUR KODAMANIVAKKAM BIT-3 CHINNA- MOWLIVAKKAM MUGALIVAKKAM PANICHERI PARANIPUTHUR SIVABURAM MALAYAMBAKKAM MADANANDAPURAM NANDAMBAKKAM VALARPURAM PERIA- BIT-1 CHENNAI ORAGADAMAHADEVINANGALAM PANICHER GERUGAMBAKKAM CHEMBARAMBAKKAM TANK SIKKARAYAPURAM KOVUR NANDAMBAKKAM T.P ALANDUR MANAPAKKAM KAPPANKOTTUR THANDALAM KOLACHERY COWL BAZAAR KUNNATHUR bit2 MOONRAM- ST.THOMAS MOUNT PICHIVAKKAM THANDALAM THIRUNAGESWARAM KATTALAI TALUK NANDAMBAKKAM CHENNAI NEMEMLI THANDALAM UDUPPAIR BIT-2 KANDIVAKKAM ELIMIANKDTTUR R.F SIRUKALATHUR KAVANUR RENDANKATTALAI VENKATEPURAM IRUNGATTUKOTTAI THARAPPAKKAM COWL BAZAAR PALAVANTANGAL KOTTUR MANANJERI (PART) THOLASAPURAM THARVUR POLICHALUR MEENAMBAKKAM KILOY T.P AYAKOLATHUR ALANDUR KUNNATHUR T.P MUNICIPALITY PURISAI EDAYARPAKKAM KATTRAMBAKKAM PALLAVARAM GUNAGARABAKKAM ETTIKUTHIMEDU ANAKAPUTHUR CONTONMENT CHENNAI NANDAMBAKKAM KUNRATHUR T.P PENNALUR ULLAGARAM T.M SIRUKILOY THIRUSOLAM KANAGAMBAKKAM THANDALAM AKKAMAPURAM MAHADEVIMANGALAM PUDUPPAIR KOTTIVAKKAM PADICHERY THIRUMUDIVAKKAM PAMMAL T.P KANNANTHANGAL POONTHANDALAM MOOVARASAMPATTU PERUNGUDI T.P PULLALORE PALLAMBAKKAM SRIPERUMBUDUR T.P AMARAMBEDU R.F PALLAVARAM PALVAKKAM ARAKONAM VALATHUR EKANAPURAM MADIPAKKAM (PART) PALANTHANDALAM MALLUR VELLORE SINGLEPADI MADURAMANGALAM VADAMANGALAM VENGADU NALLUR PADUNALLI PONDAVAKKAM -

Chengalpattu District

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2020 CHENGALPATTU DISTRICT District Disaster Management Authority Chengalpattu District, Tamil Nadu DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2020 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY CHENGALPATTU DISTRICT TAMIL NADU PREFACE Endowed with all the graces of nature’s beauty and abundance, the newly created district of Chengalpattu is a vibrant administrative entity on the North eastern part of the state of Tamil Nadu. In spite of the district’s top-notch status in terms of high educational, human development index and humungous industrial productivity, given its geography, climate and certain other socio-political attributes, the district administration and its people have to co-exist with the probabilities of hazards like floods, cyclone, Tsunami, drought, heat wave, lightning and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear emergencies. The Disastrous events in the recent past like the Tsunami of 2004, the catastrophic floods of year 2015, the cyclone of year 2016 and most recently the COVID-19 pandemic, will serve as a testament to the district’s vulnerability to such hazards. How the society responds to such vagaries of nature decides the magnitude and intensity of the destruction that may entail hazardous events. It is against this back drop, the roll of the District Disaster Management Authority can be ideally understood. The change in perspective from a relief- based approach to a more holistic disaster management approach has already begun to gain currency among the policy makers due to its substantial success in efficient handling of recent disasters across the globe. The need of the hour, therefore, is a comprehensive disaster management plan which is participative and people-friendly with the component of inter- departmental co-ordination at its crux. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette Published by Authority

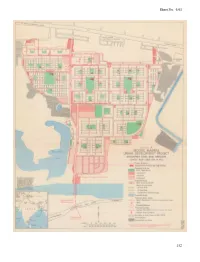

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2019 [Price : Rs. 3.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 16] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 17, 2019 Chithirai 4, Vikari, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2050 Part VI—Section 1 Notifications of interest to the General Public issued by Heads of Departments, Etc. NOTIFICations BY HEADS OF Departments, ETC. CONTENTS GENERAL NOTIFICATIONS Pages. Variations to the Approved Master Plan for the Thiruvarur Local Planning Area .. .. 132 Variations to the Approved Second Master Plan for the Chennai Metropolitan Area 2026 of Chennai Metropolitan Development Authority for Chennai Metropolitan Area .. .. 132-137 Naduveerapattu Village, Kancheepuram District, etc., Variation to the Approved Master Plan for the Madurai Local Planning Area .. .. 138 JUDICIAL NOTIFICATIONS Code of Criminal Procedure —Conferment of Powers .. .. .. .. 138 [ 131 ] DTP—VI-1-16 132 TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE [Part vi—Sec.1 NOTIFICATIONS BY HEADS OF DEPARTMENTS, ETC. GENERAL NOTIFICationS Variations to the Approved Master Plan for the Thiruvarur Local Planning Area. (Roc No. 264/2019/TR2) No. VI(1)/189/2019. In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of Section 32 of the Tamil Nadu Town and Country Planning Act, 1971 (Tamil Nadu Act 35 of 1972 and also in exercise of powers conferred by G.O. Ms. No.94, Housing and Urban Development [UD(4)1] Department, dated 12-06-2009 published in Tamil Nadu Government Gazette No.27, Part II—Section 2, in Page No.228, dated 15-07-2009, the following variations are made to the Master Plan for Thiruvarur Local Planning Area Approved under the said Act vide G.O.Ms. -

Before the Honourable National Green Tribunal Southern Zone, Chennai

BEFORE THE HONOURABLE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL SOUTHERN ZONE, CHENNAI In O.A.No.1S7 of 2016 (SZ) IN THE MATIER OF: Marvel River View County Owner's Welfare Association ...Applicant(s) With The Chairman, Airport Authority of India, New Delhi and Ors. ...Respondent(s) Repot BEFORE THE HONOURABLE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL SOUTHERN ZONE, CHENNAI In O.A.No.1S7 of 2016 (SZ) iNDEX SI.No Particular Page No 1 Report 1-8 2 Annexure-I s-is 3 Annexure-II 1&~'B BEFORE THE HONOURABLE NATIONAL GREEN TRIBUNAL SOUTHERN ZONE, CHENNAI In O.A.No.1S7 of 2016 (SZ) IN THE MADER OF: Marvel River View County Owner's Welfare Association ...Applicant( s) With The Chairman, Airport Authority of India, New Delhi and Ors. ...Respondent( s) Repot Introduction Hon'ble NGT (SZ) vide order dated 19.1.2021 directed the Joint committee to submit a further report in tune with the direction issued by the Hon'ble Tribunal as per order dated 20.02.2020 and also after considering the objections raised by the applicant to the present report submitted. The Hon'ble Tribunal vide order dated 20.2.2020 direct the committee to inspect the area in question and enumerate the violations and its impact and whether the violations can be remedied by providing precautionary measures and if not, what are the things to be done and any further action to be taken by the MoEF on this aspect. The committee may also look at the nature of action taken for the violations found and also assess the environment damage caused on account of the violations caused and suggest remedial measures for environment damage that has occurred affecting the safety of the people. -

List of Polling Stations for 28 Alandur Assembly Segment Within the 5 Sriperumbudur Parliamentary Constituency

List of Polling Stations for 28 Alandur Assembly Segment within the 5 Sriperumbudur Parliamentary Constituency Whether for Polling Sl.N Location and name of building in which All Voters or station Polling Areas o Polling Station located Men only or No Women only 1 1 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, Ward 1 union salai:, (2)-Iyyappanthangal, All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. Ward 2 kamatchi nagar:, (999)-OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: 2 2 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, Ward 1 Athithanar Nagar:, (999)- All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: 3 3 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, Ward 1 Perumal Koil St:, (2)- All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. Iyyappanthangal, Perumal Koil St:, (999)-OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: 4 4 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, Ward 1 Venugopal Nagar:, (2)- All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. Iyyappanthangal, Ward 2 mariamman koil st:, (3)- Iyyappanthangal, Venugopal Nagar:, (999)-OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: 5 5 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, Ward 2 Vanniyar Ist Mettu St:, (999)- All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: 6 6 Kundrathur Panchayat Union Primary School (1)-Iyyappanthangal, KARUMARI AMMAN KOVIL All Votes Iyyappanthangal, Iyyappanthangal 600056. STREET:, (999)-OVERSEAS ELECTORS, OVERSEAS ELECTORS: -

Sheet No. 6.01

Sheet No. 6.01 152 Sheet No. 6.02 153 Sheet No. 6.03 154 Sheet No. 6.04 155 Sheet No. 6.05 Location of TNHB Proposed Projects in CMA 49 Ariyanvoyal 47 Kollati 46 Nandiyambakkam 50 40 Minjur Madiyur 30 31 34 Sekkanjeri Nerkundram Nayar 39 Valuthigaimedu 41 43 25 29 Seemapuram Athipattu 26 Surapattu Athur Karanodai 35 27 Mahfushanpettai Sothuperambedu 32 38 43 Girudal apuram 37 Chinnamullavoyal Ennore N 42 H 28 36 Periamullavoyal 24 - Orakkadu 33 Pudupakkam Vallur 5 22 Pudur 18 Erumaivettipalayam Sholavaram Kandi gai 16 Kodipallam 17 15 PONNERI TALUK Arumandai Thirunilai 21 19 14 23 5 Ankadu Marambedu Vellivoyal Pal ayaerumai vettipalayam Sembilivaram 20 6 Kummanur Sholavaram Tank 4 Siruniyam 11 Nallur Perungayur 1 7 9 13 Kathivakkam Pannivakkam Sothupakkam 12 3 Vichoor Edayanchavadi Vijayanallur 10 10 Melsinglimedu 8 8 Palavoyal Sirugavoor Padiyanallur 2 11 7 Attanthangal Sendrambakkam Thiruthakiriyampattu 9 4 1 2 47 Alamadi Vilangadupakkam Kadapakkam 14 5 Ernavur 48 Arakkambakkam 13/2 Athivakkam 6 3 Pandeswaram Thiyambakkam Ariyalur 12 Layon 18 17/2 25 Sadayankuppam 43 Alinjivakkam 24 Elanthancheri Morai NaravariKuppam 19 23 27/2 Payasambakkam 22 Amulavoyal Vaikkadu 50 15 17/1 20 Kosapur Karlapakkam 46 39 Vadakarai Chettimedu Melpakkam Layongrant 13/1 49 Pammadukulam 40 16 MO 51 Tundakalani 21 R Roa Kadavur Redhills Vadapurambakkam d Keelakandaiyur 45 35 26 27/1 Tenambakkam Mathur Manali 42 Thiruvottiyur 53 44 Velacheri Pulikutti Vellanur 38 52 Puzhal Alathur 41 Pottur Redhills Lake 28 37 Sathangadu Vilakkupatti 29 56 l ChinnaSekkadu a -

Sudharma Brochure

Phase III Plot Survey Area in No. No. Sq.Ft. Plot -1 A 6/2 991 Plot -1 B 6/2 931 SITE PLAN PLOT - A 146’ Plot -2 A 6/2 958 23’-11” 26’-3” 26’-3” 26’-3” 26’-3” 17’ 40’.8’’ 40’-8” Plot -2 B 6/2 898 37’.9’’ 1A 2A 3A 4A 5A 6A 37’ 1” 37’ 1” 36’ 9” 36’ 9” 36’ 5” 36’ 5” 36’ 5” 36’ 5” 36’ 9” 36’ 9” 37’-9” Plot -3 A 6/2 955 29’-6” 26’-3” 26’-3” 26’-3” 26’-3” 33’-1.5” 167’.7’’ Proposed 16’ Wide Road 17’ Plot -3 B 6/2 1032 16’ 6’.10’’ 6’-10” 37’-1” 29’-6” 24’-7” 6’-10” 24’-7” 27’-10.5” 6’-10” Plot 4 A 6/2 958 25’-7” 25’-7” 20’-4” 20’-4” 1B 2B 3B 4B 5B 32’-9” 30’-2” 30’-2” 30’-2” 32’-9” 32’-9” 32’-9” Plot 4 B 6/2 950 28’-2.5” 28’-2.5” Proposed 40’-8” 23’.6’’ Wide 29’-10” 38’-4.5” 29’-10” Road 29’-10” Plot -5 A 6/2 967 68’.6’’ 100’.4’’ 4’.3’’ Existing Welcome to the world of Possibilities. After the highly Plot -5 B 6/2 895 SITE PLAN PLOT - B Road successful sales and delivery of Phase I, II Radiance now 23’.6’’ presents Sudharma III. An exclusive enclave of approved Plot -6 A 6/2 937 Residential Plots with close proximity to the Chennai All dimensions are in feet Airport. -

Kancheepuram (SC) Parliamentary Constituency Sl No

LIST OF POLLING STATIONS for 027 ShozhingallurAssembly Constituency comprised within the 03. 03. Chennai South Parliamentary Constituency Sl Locality Building in which it will Polling Area Whether for all voters or men No. be located only or women only of Polli ng Stati on 1 2 3 4 5 1.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 3 N.S.K Street , 2.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 3 Throubathiamman Koil St , 3.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 3 Vembuli Amman Koil St , 4.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 3 Jayaraman St , 5.Ullagaram 3rd Grade St. Thomas P.U.P School, 6th Main St. Thomas P.U.P School, 6th Main (M) And (R.V) Ward 4 Manimekalai St , 6.Ullagaram 3rd Grade Road Nanganallur Ullagaram East Road Nanganallur Ullagaram East (M) And (R.V) Ward 7 New Hindhu Colony , 7.Ullagaram 3rd 1 Face Face Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 7 Radha Nagar All Voters 1.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 3 Medavakkam Main Road , 2.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Lakshmi Nagar 5th Street , 3.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Lakshmi Nagar 6th Street Extension , 4.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Lashmi Nagar 10th Street , 5.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Azhvar nagar 1st Street , 6.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Azhvar Nagar 2nd Street , 7.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Azhvar Nagar 3rd Street , 8.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 16 Azhvar Nagar 4th Street , 9.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 1 Mackmilan Colony 1st Street , 10.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) And (R.V) Ward 1 Mackmilan Colony 2nd Street , 11.Ullagaram 3rd Grade (M) St. -

Volume 9, Issue Special, February 2019, National Conference On

Volume 9, Issue Special, February 2019, National Conference On Technology Enabled Teaching And Learning In Higher Education, School of Management Studies, VISTAS, Chennai, India Influence of E-Technologies on School Education and Its Impact on User Satisfaction S. Srivathsani1 and Dr. S. Vasantha2 1(MPhil Research Scholar, School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science, Technology &Advanced Studies (VISTAS), Chennai, India) 2(Corresponding Author: Professor, School of Management Studies, Vels Institute of Science, Technology & Advanced Studies (VISTAS), Chennai, India) Abstract The world has witnessed the increasing and humungous power of e-technologies in almost every aspect of human life. Be it banking, education, finance, entertainment or healthcare, there are virtually no fields which has not been influenced by the e-technologies. In today’s world of digitalisation, organizations have realized the power of e-technologies and are being driven to use e-technologies to match the global paradigms. The education industry unanimously agrees to the fact that it is undergoing a positive transformation due to the application of e-technologies. Application of e-technologies involves the usage of ICT (Information and Communication Technologies) with the help of Internet or Intranet.ETechnologies in education can take the form of e-learning, usage of ICT equipments with Internet in classrooms, usage of Interactive whiteboards, mobile devices and so on. This paper deals with the role of e-technologies in the field of education in India. It also discusses about the scenario of application of e-technologies and ICT in schools of the rural areas of Kanchipuram District, TamilNadu. Keywords: E-Technology, ICT, Education, Internet, E-Learning 1.Introduction UNESCO defines ICT as amalgamation of information technology with the communication technology.