Big Dig, Big Bridge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tolling and Transponders in Massachusetts

DRIVING INNOVATION: TOLLING AND TRANSPONDERS IN MASSACHUSETTS By Wendy Murphy and Scott Haller White Paper No. 150 July 2016 Pioneer Institute for Public Policy Research Pioneer’s Mission Pioneer Institute is an independent, non-partisan, privately funded research organization that seeks to improve the quality of life in Massachusetts through civic discourse and intellectually rigorous, data-driven public policy solutions based on free market principles, individual liberty and responsibility, and the ideal of effective, limited and accountable government. This paper is a publication of the Center for Better Government, which seeks limited, accountable government by promoting competitive delivery of public services, elimination of unnecessary regulation, and a focus on core government functions. Current initiatives promote reform of how the state builds, manages, repairs and finances its transportation assets as well as public employee benefit reform. The Center for School Reform seeks to increase the education options available to parents and students, drive system-wide reform, and ensure accountability in public education. The Center’s work builds on Pioneer’s legacy as a recognized leader in the charter public school movement, and as a champion of greater academic rigor in Massachusetts’ elementary and secondary schools. Current initiatives promote choice and competition, school-based man- agement, and enhanced academic performance in public schools. The Center for Economic Opportunity seeks to keep Massachusetts competitive by pro- moting a healthy business climate, transparent regulation, small business creation in urban areas and sound environmental and development policy. Current initiatives promote market reforms to increase the supply of affordable housing, reduce the cost of doing business, and revitalize urban areas. -

Southbay Report.Qxd

August 30, 2004 Mr. Mark Maloney Director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority City of Boston 9th Floor City Hall Plaza Boston, Massachusetts Dear Mr. Maloney- On behalf of the South Bay Planning Study Task Force, I am pleased to present to you the South Bay Planning Study - Phase One. Over the past seven months our group of seventeen devoted volunteers, including representatives from Chinatown and the Leather District, have worked to create a plan for this important new part of the City of Boston. The vision that has emerged from our efforts is exciting and broad-reaching, and at the same time identifies many issues that will require further study in the second phase of our work. Conclusions that we have reached include: The project should be expanded from a set of parcels totaling 10 acres to a District consisting of 20 acres, transforming it from a project to a neighborhood. The district, which currently consists of highway infrastructure that divides and separates it from the neighborhoods, should become a series of city blocks that knit together and connect many important assets of the City of Boston. The southern entrance into the City that is now dominated by transportation infrastructure should instead be revealed as a great gateway portal for the City from the South. We must collectively work towards providing housing for all income levels and towards providing employment and employment training to benefit the adjacent neighborhoods. We should create a terminus to the Rose Kennedy Greenway in the form of a signature park that will help to meet the recreational needs of the neighborhoods and connect the Greenway to Fort Point Channel. -

Big Dig Benefit: a Quicker Downtown Trip Turnpike Authority Report Cites Business Gain

Big Dig benefit: A quicker downtown trip Turnpike Authority report cites business gain By Mac Daniel February 15, 2006 The $14.6-billion Big Dig project has cut the average trip through the center of Boston from 19.5 minutes to 2.8 minutes and has increased by 800,000 the number of people in Eastern Massachusetts who can now get to Logan International Airport in 40 minutes or less, according to a report that is scheduled to be released today. The report is the first to analyze and link the drive- time benefits of the project to its economic impact since the Big Dig built its final onramp last month. The report relies on data obtained since milestones were completed in 2003, such as opening of the Ted Williams Tunnel to all traffic and opening of the northbound and southbound Interstate 93 tunnels. Officials at the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority, which manages the project, released the executive summary portion of the report to the Globe yesterday. The improved drive times are projected to result in savings of $167 million annually: $24 million in vehicle operating costs and $143 million in time. The report estimates that the Big Dig will generate $7 billion in private investment and will create tens of the thousands of jobs in the South Boston waterfront area and along the I-93 corridor. The report was authored by the Economic Development Research Group, Inc., a Boston-based consulting firm, at the behest of the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority, which paid about $100,000 for the research, much of which was gathered from agencies such as the Boston Redevelopment Authority and the Boston Metropolitan Planning Organization, officials said. -

America's Tunnels / by Marcia Amidon Lusted

Infrastructure of AMERICA’S Tunnels Marcia Amidon Lusted 2001 SW 31st Avenue Hallandale, FL 33009 www.mitchelllane.com Copyright © 2018 by Mitchell Lane Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Design: Sharon Beck Editor: Jim Whiting Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Lusted, Marcia Amidon, author. Title: Infrastructure of America's tunnels / by Marcia Amidon Lusted. Description: Hallandale, FL : Mitchell Lane Publishers, [2018] | Series: Engineering feats | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Ages 9-13. Identifiers: LCCN 2017052245 | ISBN 9781680201505 (library bound) Subjects: LCSH: Tunnels—United States—Juvenile literature. | Infrastructure (Economics)—United States—Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC TA804.U6 L87 2018 | DDC 624.1/930973—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052245 eBook ISBN: 9-781-6802-0151-2 PHOTO CREDITS: Cover, p. 1—Don Ramey Logan/cc by-sa 4.0; David Wilson/cc by-sa 2.0; Pedro Szekely/cc-by-sa 2.0; U.S. Navy/Public domain; US DoD Service/U.S. Federal Government/Public domain; Sahmeditor/Nicole Ezell/Public domain; Bernard Gagnon/GFDL/cc by-sa 3.0; Trevor Brown/EyeEm/Getty Images; (interior)—Hulinska_Yevheniia/Getty Images Plus. Cover, pp. 1, 6—Andrew Haliburton/Alamy Stock Photo; pp. 8-9—Michael Dwyer/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 10— Darren McCollester/Stringer/ Getty Images News, (inset)—Marcbela/Public domain; p. 11—AP Photo/Michael Dwyer, File/Associated Press; p. 12—AP Photo/ Mel Evans/Associated Press; p. -

Central Artery/Tunnel Project: a Precast Bonanza

PART 1 Central Artery/Tunnel Project: A Precast Bonanza by Vijay Chandra, P.E. Anthony 1. Ricci, RE. Senior Vice President Chief Bridge Engineer Parsons Brinckerhoff Quade & Central Artery/Tunnel Project Douglas, Inc. Massachusetts Turnpike Authority New York, New York Boston, Massachusetts This article provides an overview of the monumental efforts of Massachusetts transportation officials, their engineering consultants, and multitudes of construction industry professionals to ease congestion, improve motorist safety, and address issues of environmental quality in the heart of Boston, Massachusetts. The Central Artery/Tunnel Project is the largest highway construction job ever undertaken in the United States, involving many diverse types of precast concrete construction. maj or transportation infrastructure undertaking, • Standardized temporary structures utilizing precast con billed as “The Big Dig,” is transforming traffic op crete elements. A erations in and around Boston, Massachusetts. This • Precast segmental box girders integrated into cast-in-place $13.2 billion project, the biggest and most complex trans columns to provide seismically resistant connections. portation system ever undertaken in the United States, is • Precast segmental boxes cut at a skew to connect them on significant not only in this country, but worldwide. Nu either side of straddle bents. merous innovative construction techniques are being used, The project has brought out the best that precast con including: crete technology has to offer — in many cases utilizing • Precast tunnels jacked under railroad embankments. cutting edge techniques — and has been of immeasurable • Deep soil mixing to stabilize land reclaimed from the value to New England’s precasting industry. Precasters, ocean. faced with many complex and daunting challenges, are • Precast concrete immersed tube tunnels. -

Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts

All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts Rachel Bain Massachusetts Deputy Registrar And Stephen M. Collins MassDOT Director of Statewide Tolling Presented to the AAMVA 2014 Workshop and Law Institute St. Louis, Mo March 13, 2014 All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts Topics • Previous Presentation – P. J. Wilkins • MassDOT Background and Organization • MassDOT Tolls and RMV Working Together • Tolls - Why All Electronic Tolling (AET)? • Requirements when Tolling by License Plate • Enforcement and Reciprocity Needs • Inter-agency Agreements • Challenges 3/13/2014 2 All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts • July 2013 Presentation Dover, Del. 3/13/2014 3 All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts • MassDOT Background – Previously - Separate Agencies • MBTA • Massachusetts Turnpike Authority (est. 1952) • Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles (RMV) • MassHighway, other departments – 2009 Commonwealth of Massachusetts Transportation Reform • Merger = MassDOT 3/13/2014 4 All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts • MassDOT Background – Tolls Group and the RMV worked on several joint initiatives: • Toll Violation Processing – Mass Plate Look-Ups – RMV ‘Marking’ for Enforcement – RMV Collecting Fines and Fees on Behalf of Tolls Group • Co-Locating Services – Same Customer Base 3/13/2014 5 All Electronic Tolling (AET) and You: DMV Impacts • MassDOT Background – Today’s Organization Secretary of Board of Directors Transportation MBTA GM / Administrator – Administrator – MassDOT Rail and Registrar / -

A Big Dig Cost Recovery Referral: Paving Mismanagement by Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff

Office of the Inspector General Commonwealth of Massachusetts Gregory W. Sullivan Inspector General A Big Dig Cost Recovery Referral: Paving Mismanagement by Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff January 2005 January 2005 Dear Chairman Amorello: I am forwarding for your review the most recent findings from my Office’s continuing review of potential Big Dig cost recovery cases. These findings refer to poor contract redesign and construction management on the part of the joint venture of Bechtel/Parsons Brinckerhoff (B/PB). Specifically, my Office found that B/PB failed to properly manage the paving of the East Boston roadway. A number of issues point to B/PB mismanagement that include: • B/PB approved and designed seven years of a quick fixes instead of a permanent roadway replacement; • B/PB’s design failed to account for manhole frames and covers in the roadway; and • B/PB paid a section design consultant for work that knowingly would never be used. As a result of B/PB’s mismanagement, taxpayers have paid approximately $7 million for seven years of quick fixes and the eventual permanent pavement replacement. This is particularly troubling because paving occurs regularly in construction projects not only in the Commonwealth but also across the country. Yet, it took B/PB over seven years to permanently repair the East Boston roadway. I recommend that this matter be referred to the Turnpike Authority’s cost recovery team. My staff is available to assist you in any continuing examination of this or any other issue. Thank you. Sincerely, Gregory W. Sullivan Inspector General This page intentionally left blank. -

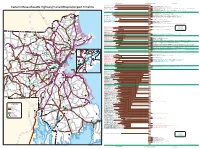

Time Line Map-Final

RAILROAD/TRANSIT HIGHWAY/BICYCLE/AIRPORT LEGISLATIVE Green Line to Medford (GLX), opened 2021 2021 2020 2019 Mass Central Rail Trail Wayside (Wayland, Weston), opened 2019 Silver Line SL3 to Chelsea, opened 2018 2018 Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Phase 2A (Westford, Carlise, Acton), opened 2018 Worcester CR line, Boston Landing Station opened 2017 2017 Eastern Massachusetts Highway/Transit/Bicycle/Airport Timeline Fitchburg CR line (Fitchburg–Wachusett), opened 2016 2016 MassPike tollbooths removed 2016 2015 Cochituate Rail Trail (Natick, Framingham), opened 2015, Upper Charles Rail Trail (Milford, Ashland, Holliston, Hopkinton), opened 2015, Watertown Greenway, opened 2015 Orange Line, Assembly Station opened 2014 2014 Veterans Memorial Trail (Mansfield), opened 2014 2013 Bay Colony Rail Trail (Needham), opened 2013 2012 Boston to Border South (Danvers Rail Trail), opened 2012, Northern Strand Community Trail (Everett, Malden, Revere, Saugus), opened 2012 2011 2010 Boston to Border Rail Trail (Newburyport, Salisbury), opened 2010 Massachusetts Department of TransportationEstablished 2009 Silver Line South Station, opened 2009 2009 Bruce Freeman Rail Trail Phase 1 (Lowell, Chelmsford Westford), opened 2009 2008 Independence Greenway (Peabody), opened 2008, Quequechan R. Bikeway (Fall River), opened 2008 Greenbush CR, reopened 2007 2007 East Boston Greenway, opened 2007 2006 Assabet River Rail Trail (Marlborough, Hudson, Stow, Maynard, Acton), opened 2006 North Station Superstation, opened 2005 2005 Blackstone Bikeway (Worcester, Millbury, Uxbridge, Blackstone, Millville), opened 2005, Depressed I-93 South, opened 2005 Silver Line Waterfront, opened 2004 2004 Elevated Central Artery dismantled, 2004 1 2003 Depressed I-93 North and I-90 Connector, opened 2003, Neponset River Greenway (Boston, Milton), opened 2003 Amesbury Silver Line Washington Street, opened 2002 2002 Leonard P. -

Commercial User Guide Page 1 FINAL 1.12

E-ZPass Account User Guide Welcome to the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission’s E-ZPass Commercial Account program. With E-ZPass, you will be able to pass through a toll facility without exchanging cash or tickets. It helps ease congestion at busy Pennsylvania Turnpike interchanges and works outside of Pennsylvania for seamless travel to many surrounding states; anywhere you see the purple E-ZPass sign (see attached detailed listing). The speed limit through E-ZPass lanes is 5-miles per hour unless otherwise posted. The 5-mile per hour limit is for the safety of all E-ZPass customers and Pennsylvania Turnpike employees. If you have any questions about your E-ZPass account, please contact your company representative or call the PTC E-ZPass Customer Service Center at 1.877.PENNPASS (1.877.736.6727) and ask for a Commercial E-ZPass Customer Service Representative. Information is also available on the web at www.paturnpike.com . How do I install my E-ZPass? Your E-ZPass transponder must be properly mounted following the instructions below to ensure it is properly read. Otherwise, you may be treated as a violator and charged a higher fare. Interior Transponder CLEAN and DRY the mounting surface using alcohol (Isopropyl) and a clean, dry cloth. REMOVE the clear plastic strips from the back of the mounting strips on the transponder to expose the adhesive surface. POSITION the transponder behind the rearview mirror on the inside of your windshield, at least one inch from the top. PLACE the transponder on the windshield with the E-ZPass logo upright, facing you, and press firmly. -

Why Did It Fail?

Why Did It Fail? David W. Fowler The University of Texas at Austin CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar Ausn, Texas Why do structures fail? • Many reasons: – Design (45 to 55%) – Construction (20 to 30% – Materials (15 to 20%) – Administrative (10%) – Maintenance (5 to 10%) CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar 2 Ausn, Texas Specific Causes 1. Ignorance/incompetence/inexperience 2. Blunders, errors, and omissions 3. Lack of supervision within organization 4. Lack of communication or continuity 5. Lack of coordination 6. Overemphasis on the bottom line (saving money) 7. Administrative deficiencies 8. Maintenance CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar 3 Ausn, Texas Role of Forensic Engineer • Determine the cause of failure • Persuasively communicate his findings to the client and/or appropriate judicial venue • And in some cases, recommend corrections or repairs CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar 4 Ausn, Texas We should learn from failures • History is one of our greatest teachers • Some our greatest lessons have come from failures • Unfortunately, the cause of many failures are sealed by agreement of the involved party and the public never learns some very important lessons • University of Maryland experience CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar 5 Ausn, Texas Let’s look at some failures… • Tacoma Narrows Bridge Failure: Fowler • Big Dig Ceiling Panel Failure: Fowler • Case Study of Foundation Failure: Chancey CAEE Annual Alumni Ethics Seminar 6 Ausn, Texas TacomaTacoma NarrowsNarrows BridgeBridge • The most famous bridge failure in the U.S. • It was originally opened to traffic July 1, 1940. • It collapsed four months later, November 7, 1940, at 11:00 am. • It had been exhibiting signs of aerolastic flutter since it opened. -

Transportation Impacts of the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority and the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel Project

Transportation Impacts of the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority and the Central Artery/Third Harbor Tunnel Project Volume I February 2006 After Before IFC Economic Impact of the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority & Related Projects Volume I: The Turnpike Authority as a Transportation Provider Prepared for: Massachusetts Turnpike Authority 10 Park Plaza, Suite 4160, Boston, MA 02116 Prepared by: Economic Development Research Group, Inc. 2 Oliver Street, 9th Floor, Boston, MA 02109 Table of Contents Table of Contents Preface.........................................................................................................................i Summary of Volume I Findings...................................................................................i Introduction ................................................................................................................1 1.1 Analysis Methodology............................................................................................1 1.4 Organization of the Report .....................................................................................2 Overview of Projects...................................................................................................3 2.1 I-93 Central Artery Projects ...................................................................................3 2.2 I-90 Turnpike Extension to Logan Airport.............................................................5 2.3 New Public Safety Services for Boston Area Highways........................................6 -

Metropolitan Highway System and 2018 Triennial Report Review of Consultant Findings & Next Steps Draft

Metropolitan Highway System And 2018 Triennial Report Review of Consultant Findings & Next Steps Draft Overview of the Metropolitan Highway System (MHS) • Triennial Report on condition of the Metropolitan Highway System (MHS) goes beyond the required 3 year timeframe to look at overall State of Good Repair • Reports supplements other asset management systems and reports to shape capital investment program driven by asset condition • Achieving State of Good Repair will need to occur over an extended period to address challenges of sequencing projects without unduly inconveniencing drivers or limiting access to Boston 2/12/2019 Draft for Discussion and Policy Purposes Only 2 Components of the Metropolitan Highway System (MHS) • Legislatively defined to include predominately tolled highway system that consists of the Boston Extension, the Callahan Tunnel, the Central Artery, the Central Artery North Area of the Mass Turnpike, the Sumner Tunnel, and the Ted Williams Tunnel, as defined in M.G.L. c. 6C, § 1. The collection of assets span 75 years of infrastructure construction • Includes all harbor tunnels, bridges and support structures like vent buildings or pump stations • Tobin Bridge is excluded for purposes of the Triennial Report FACILITY CONSTRUCTION ERA Sumner/Callahan Tunnels Sumner 1930’s/Callahan 1960’s I90 Boston Extension (Weston to Boston) 1964 Central Artery North Area Tunnel (CANA) 1980’s Central Artery/Tunnel Ted Williams Tunnel 1996; Central Artery Tunnels 2003 2/12/2019 Draft for Discussion and Policy Purposes Only 3 Triennial