Comics Aren't (Just) Funny

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Kids Love Superman Because He Can Fly… Many Kids Like Batman and the Tools of a Spy

Some kids love Superman because he can fly… Many kids like batman and the tools of a spy. Hulk smashes through walls without even a try. But Jesus Christ is my favorite hero – I’ll tell you why, and how you too can become a superhero for the Kingdom of God. Jesus Christ The Real Superhero All your children shall be taught by the LORD, and great shall be the peace of your children. Isaiah 54:13 Do YOU like Superheroes? How many of you have seen a movie or a cartoon about a superhero? Who here likes Superman? Who likes Spiderman? Is there anyone here who likes Batman? Those are just a few of the most popular superheroes. But these super heroes are all just characters on TV and in books. There is one REAL Superhero who actually lived on Earth just like you and me, and His name is JESUS! TEACHERS: Remember to make it fun and interactive. Go as slow as you need to. The early objective is to distinguish between fictional superheroes (like Superman) and a real life superhero (Jesus Christ). Please feel free to refer to the scriptures (in the boxes at the bottom of each page) to add meaning and depth to your lessons, especially for the older children. THE JESUS SUPERHERO STORY You might know that God is the creator of all things -- the earth, the moon, the stars, the sun, the sky, the trees, the animals, and the entire universe… But did you know God has a son? Did you know that his son lived right here, on earth, as just a mortal man? That’s Jesus! And He is my favorite superhero of all-time. -

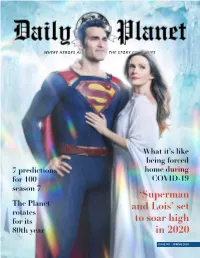

'Superman and Lois' Set to Soar High in 2020

WHERE HEROES ARE BORN AND THE STORY CONTINUES What it’s like being forced 7 predictions home during for 100 COVID-19 season 7 ‘Superman The Planet and Lois’ set rotates for its to soar high 80th year in 2020 ISSUE 001 · SPRING 2020 Resources for COVID-19 There is no doubt that concerns over the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) have caused a major disruption to everyday life IN THIS ISSUE across the planet. Education centers, public venues and a variety of shopping centers have all shuttered in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19. Entire countries have closed off their borders, preventing nonessential travel and closing SUPERMAN AND LOIS SET TO SOAR HOW GENE LUEN YANG HELPED ME entire continents off. HIGH IN 2020 SEE THE WORLD These are truly unprecedented and historic times where community means the most. To assist in curbing the spread of 16 08 the Coronavirus, health experts have advised that people remain home, participate in safe social distancing and practice appropriate hygiene for illness prevention. FROM INDEPENDENT COLLEGE STUDENT LOVE MOTIVATING EVERYTHING IS TO SOCIAL DISTANCING AT MY The Planet has compiled a list of resources for those in need and those who are looking to assist with recovery efforts. AN EXHAUSTED TROPE PARENTS HOUSE Stay safe and stay healthy, everyone. 05 14 The Center for Disease Control (CDC) says that if you have a fever or cough, you might have COVID-19. Most people experience mild forms of COVID-19 and are able to recover at home. Keep track of your symptoms. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10. -

RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2000 RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets Willard Largent Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Largent, Willard, "RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets" (2000). Purdue University Press Books. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. RAF Wings over Florida RAF Wings over Florida Memories of World War II British Air Cadets DE Will Largent Edited by Tod Roberts Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright q 2000 by Purdue University. First printing in paperback, 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-992-2 Epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-993-9 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-138-7 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier hardcover edition as follows: Largent, Willard. RAF wings over Florida : memories of World War II British air cadets / Will Largent. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55753-203-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Largent, Willard. 2. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, American. 4. Riddle Field (Fla.) 5. Carlstrom Field (Fla.) 6. World War, 1939±1945ÐPersonal narratives, British. 7. Great Britain. Royal Air ForceÐBiography. I. -

“Justice League Detroit”!

THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! t 201 2 A ugus o.58 N . 9 5 $ 8 . d e v r e s e R s t h ® g i R l l A . s c i m o C C IN THE BRONZE AGE! D © & THE SATELLITE YEARS M T a c i r e INJUSTICE GANG m A f o e MARVEL’s JLA, u g a e L SQUADRON SUPREME e c i t s u J UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CROSSOVERS 7 A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN 0 8 2 “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY 6 7 7 CONWAY & DAN JURGENS 2 8 5 6 And the team fans 2 8 love to hate — 1 “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “BaTman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray . s c i m COVER COLORIST o C BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury .........................................................2 Glenn “Green LanTern” WhiTmore C D © PROOFREADER & Whoever was sTuck on MoniTor DuTy FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 M T . A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators a c i r SPECIAL THANKS e m Jerry Boyd A Rob Kelly f o Michael Browning EllioT S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers ................29 e u Rich Buckler g Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… a e L Russ Burlingame Brad MelTzer e c i T Snapper Carr Mi ke’s Amazing s u J Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme ....................................33 e h T ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders g n i r Gerry Conway Eri c Nolen- r a T s DC Comics WeaThingTon , ) 6 J. -

PDF Download Wonder Woman by George Perez Omnibus Vol. 2

WONDER WOMAN BY GEORGE PEREZ OMNIBUS VOL. 2 Author: George Perez Number of Pages: 500 pages Published Date: 23 May 2017 Publisher: DC Comics Publication Country: United States Language: English ISBN: 9781401272388 DOWNLOAD: WONDER WOMAN BY GEORGE PEREZ OMNIBUS VOL. 2 Wonder Woman By George Perez Omnibus Vol. 2 PDF Book This new edition is easier to read and of greater practical interest to practitioners. forgottenbooks. A comprehensive questionnaire will help men or their wives or partners pick up any changes that could be early warning signs. " A Dictionary of CreekMuskogee5000-WORD ENGLISH-GERMAN VOCABULARY The use of this 5000 word German vocabulary will allow you to understand simple texts and will give you much needed confidence in everyday conversation. Lifeline Across the Sea: Mercy Ships of the Second World War and their Repatriation MissionsThe topsail schooner 'Lady of St Kilda' was built in 1834 for the wealthy Devon landowner Sir Thomas Dyke Acland. Find more at www. CONTENTS "The Adventures of Mouse Deer" (Indonesia, Malaysia) "The Calabash Kids" (Tanzania) "The Hidden One" (Native America) "The Boy Who Wanted the Willies" (Europe) "The Princess Mouse" (Finland) "The Legend of Slappy Hooper" (U. All learning is practiced across speaking, listening, reading, and writing exercises, offering rounded preparation for work, travel, study, and exams. Facts on Sloths for Sale, Eating, Teeth, Habitat, Health, Endangered Status and CharitiesAMAZON BEST SELLER BEST GIFT IDEAS This incredible adult coloring book by best-selling artist is the perfect way to relieve stress and aid relaxation while enjoying beautiful and highly detailed images. Although their contributions have been acknowledged where they occur in the text, I should like to place on record here my indebtedness to the unfailing courtesy which I have always received. -

Justice League: Origins

JUSTICE LEAGUE: ORIGINS Written by Chad Handley [email protected] EXT. PARK - DAY An idyllic American park from our Rockwellian past. A pick- up truck pulls up onto a nearby gravel lot. INT. PICK-UP TRUCK - DAY MARTHA KENT (30s) stalls the engine. Her young son, CLARK, (7) apprehensively peeks out at the park from just under the window. MARTHA KENT Go on, Clark. Scoot. CLARK Can’t I go with you? MARTHA KENT No, you may not. A woman is entitled to shop on her own once in a blue moon. And it’s high time you made friends your own age. Clark watches a group of bigger, rowdier boys play baseball on a diamond in the park. CLARK They won’t like me. MARTHA KENT How will you know unless you try? Go on. I’ll be back before you know it. EXT. PARK - BASEBALL DIAMOND - MOMENTS LATER Clark watches the other kids play from afar - too scared to approach. He is about to give up when a fly ball plops on the ground at his feet. He stares at it, unsure of what to do. BIG KID 1 (yelling) Yo, kid. Little help? Clark picks up the ball. Unsure he can throw the distance, he hesitates. Rolls the ball over instead. It stops halfway to Big Kid 1, who rolls his eyes, runs over and picks it up. 2. BIG KID 1 (CONT’D) Nice throw. The other kids laugh at him. Humiliated, Clark puts his hands in his pockets and walks away. Big Kid 2 advances on Big Kid 1; takes the ball away from him. -

Wonder Woman by Greg Rucka Vol. 1 by Greg Rucka Book

Wonder Woman By Greg Rucka Vol. 1 by Greg Rucka book Ebook Wonder Woman By Greg Rucka Vol. 1 currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook Wonder Woman By Greg Rucka Vol. 1 please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: Wonder Woman by Greg Rucka (Book 1)+++Paperback:::: 392 pages+++Publisher:::: DC Comics (July 19, 2016)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN-10:::: 1401263321+++ISBN-13:::: 978-1401263324+++Product Dimensions::::6.6 x 0.6 x 10.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 1401263321 ISBN13 978-1401263 Download here >> Description: When an ancient ritual requires Wonder Woman to protect a young woman from anyone who threatens her, it pits the Amazon Warrior against her Justice League ally, Batman!And while an array of enemies, including Silver Swan and the more dangerous than ever Dr. Psycho, attack Wonder Woman on all fronts, it’s the publication of Princess Diana’s book that opens her to an assault by a new and deadly foe – the malevolent Veronica Cale – and places Wonder Woman’s island homeland of Themyscira in grave danger.Best-selling writer Greg Rucka (DETECTIVE COMICS) teams with artists JG Jones (FINAL CRISIS), Drew Johnson (SUPERGIRL), Shane Davis (SUPERMAN: EARTH ONE) and more for the start of his legendary run on the title as Wonder Woman stands against mortal foes and faces the machinations of the gods themselves!Collects the highly sought after WONDER WOMAN: THE HIKETEIA and WONDER WOMAN #195-205. The first volume of Greg Ruckas tremendous run on Wonder Woman including the amazing story Hiketeia. -

English 480: the Modern American Superhero Spring 2016 Professor Ben Saunders

ENGLISH 480: THE MODERN AMERICAN SUPERHERO SPRING 2016 PROFESSOR BEN SAUNDERS Office Hours: Wednesdays, 9 a.m. —12 noon (366 PLC) E-mail: [email protected] Description: Once upon a time, the four-color world of the superhero was a comfortingly simple place. Whether they came from distant galaxies, other dimensions, or our home planet, the super-powered beings of the 1940s and 50s were secure in their sense of righteousness and saw no contradiction in the alignment of truth and justice with the American way. But in the 1960s superheroes experienced a crisis of confidence. They became more neurotic, more driven by guilt than moral rectitude, and more likely to be feared and misunderstood than admired and revered. Throughout the 1970s, things got worse. The Green Lantern was accused of racism; Spider-Man’s girlfriend was murdered; Superman wondered about his own relevance; Iron Man turned to the bottle. By the 1980s it had become hard to tell the heroes from the villains. In Watchmen, the single most influential superhero narrative of the late 20th century, super-beings were imagined variously as weapons in the Cold War, wannabe celebrities chasing the corporate dollar, self-loathing closet cases, and damaged psychotics. When the comic book industry underwent one of its periodic collapses in the 1990s it looked like it was all over for the spandex set. But today, superheroes are enjoying a commercial renaissance; indeed, the figure of the superhero has become one of the dominant fantasies of our present moment. What does all this tell us about the genre? And what does it say about us our culture, politics, and values? In this class we will map the path of the American superhero and consider the ways in which that journey reflects larger processes of social change. -

Who Is This New Hero? by Lois Lane

Metropolis NOW! October 2014 Who is this New Hero? by Lois Lane The New Comer Emblazoned with a golden eagle across her was accompanied by two other individuals a tall blond chest a new superhero has been taking the scene in man of military built who did not look to pleased recent months. But step back people, this one is a girl. that I was there, and a beautiful plump black women Or more precisely a woman. Princess Diana of Themy- in an immaculate pink pants suit. Wonder Woman scira, otherwise known as Wonder Woman, has joined informed me that they were Steve Trevors and Etta the pantheon of superheroes known as the Justice Cahndi, representatives of the U.S. Government that league as they watch over this fragile planet. But who were assisting her to acclimate to what she termed, is this woman of wonder? Where is she from? What is “Man’s World.” Before I could even ask about her ties her purpose here? These questions and more is what to the U.S. government I was informed rather stern- lead this reporter to track down this power house, ly that that topic would not be discussed that day by armed only with a pen, paper, and tape recorder. Ms.Cahndi. I grumbled to myself at first for fear that It wasn’t hard to find Wonder Woman, I simply I would have no story from this meeting, but my fears followed the path of destruction during last months were pushed aside by the openness Wonder Woman altercation with Gorilla Grodd that destroyed a large had about other subjects. -

A Methodological Guide for Educational Approaches to the European Folk Myths and Legends

Angela ACQUARO, Anthi APOSTOLIDOU, Lavinia ARAMĂ, Carmen-Mihaela BĂJENARU, Anetta BIENIARZ, Danuta BIENIEK, Joanna BRYDA-KŁECZEK, Mariele CARDONE, Sérgio CARLOS, Miguel CARRASQUEIRA, Daniela CERCHEZ, Neluța CHIRICA, Corina- Florentina CIUPALĂ, Florica CONSTANTIN, Mădălina CRAIOVEANU, Simona-Diana CRĂCIUN, Giovanni DAMBRUOSO, Angela DECAROLIS, Sylwia DOBRZAŃSKA, Anamaria DUMITRIU, Bernadetta DUŚ, Urszula DWORZAŃSKA, Alessandra FANIUOLO, Marcin FLORCZAK, Efstathia FRAGKOGIANNI, Ramune GEDMINIENE, Georgia GOGOU, Nazaré GRAÇA, Davide GROSSI, Agata GRUBA, Maria KAISARI, Maria KATRI, Aiste KAVANAUSKAITE LUKSE, Barbara KOCHAN, Jacek LASKA, Vania LIUZZI, Sylvia MASTELLA, Silvia MANEA, Lucia MARTINI, Paola MASCIULLI, Paula MELO, Ewa MICHAŁEK, Vittorio MIRABILE, Sandra MOTUZAITE-JURIENE, Daniela MUNTEANU, Albert MURJAS, Maria João NAIA, Asimina NEGULESCU, Helena OLIVEIRA, Marcin PAJA, Magdalena PĄCZEK, Adina PAVLOVSCHI, Małgorzata PĘKALA, Marioara POPA, Gitana PETRONAITIENE, Rosa PINHO, Monika POŹNIAK, Erminia RUGGIERO, Ewa SKWORZEC, Artur de STERNBERG STOJAŁOWSKI, Annalisa SUSCA, Monika SUROWIEC-KOZŁOWSKA, Magdalena SZELIGA, Marta ŚWIĘTOŃ, Elpiniki TASTANI, Mariusz TOMAKA, Lucian TURCU A METHODOLOGICAL GUIDE FOR EDUCATIONAL APPROACHES TO THE EUROPEAN FOLK MYTHS AND LEGENDS ISBN 978-973-0-34972-6 BRĂILA 2021 Angela ACQUARO, Anthi APOSTOLIDOU, Lavinia ARAMĂ, Carmen-Mihaela BĂJENARU, Anetta BIENIARZ, Danuta BIENIEK, Joanna BRYDA-KŁECZEK, Mariele CARDONE, Sérgio CARLOS, Miguel CARRASQUEIRA, Daniela CERCHEZ, Neluța CHIRICA, Corina- Florentina CIUPALĂ, -

The Last Amazon Wonder Woman Returns

Save paper and follow @newyorker on Twitter Annals of Entertainment SEPTEMBER 22, 2014 ISSUE The Last Amazon Wonder Woman returns. BY JILL LEPORE Wonder Woman, introduced in 1941, was a creation of utopian feminism, inspired by Margaret Sanger and the ideals of free love. PHOTOGRAPH BY GRANT CORNETT he Wonder Woman Family Museum occupies a one-room bunker beneath a two-story house on a hilly street in Bethel, CTonnecticut. It contains more than four thousand objects. Their arrangement is higgledy-piggledy. There are Wonder Woman lunchboxes, face masks, coffee mugs, a Frisbee, napkins, record- players, T-shirts, bookends, a trailer-hitch cover, plates and cups, pencils, kites, and, near the floor, a pressed-aluminum cake mold, her breasts like cupcakes. A cardboard stand holds Pez dispensers, red, topped with Wonder Woman’s head. Wonder Woman backpacks hang from hooks; sleeping bags are rolled up on a shelf. On a ten- foot-wide stage whose backdrop depicts ancient Greece—the Parthenon atop the Acropolis—Hippolyte, queen of the Amazons, a life-size mannequin wearing sandals and a toga, sits on a throne. To her left stands her daughter, Princess Diana, a mannequin dressed as Wonder Woman: a golden tiara on top of a black wig; a red bustier embossed with an American eagle, its wings spread to form the letters “WW”; a blue miniskirt with white stars; bracelets that can stop bullets; a golden lasso strapped to her belt; and, on her feet, super- kinky knee-high red boots. Nearby, a Wonder Woman telephone rests on a glass shelf. The telephone is unplugged.