The Last Amazon Wonder Woman Returns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossmedia Adaptation and the Development of Continuity in the Dc Animated Universe

“INFINITE EARTHS”: CROSSMEDIA ADAPTATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CONTINUITY IN THE DC ANIMATED UNIVERSE Alex Nader A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Jeff Brown, Advisor Becca Cragin © 2015 Alexander Nader All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeff Brown, Advisor This thesis examines the process of adapting comic book properties into other visual media. I focus on the DC Animated Universe, the popular adaptation of DC Comics characters and concepts into all-ages programming. This adapted universe started with Batman: The Animated Series and comprised several shows on multiple networks, all of which fit into a shared universe based on their comic book counterparts. The adaptation of these properties is heavily reliant to intertextuality across DC Comics media. The shared universe developed within the television medium acted as an early example of comic book media adapting the idea of shared universes, a process that has been replicated with extreme financial success by DC and Marvel (in various stages of fruition). I address the process of adapting DC Comics properties in television, dividing it into “strict” or “loose” adaptations, as well as derivative adaptations that add new material to the comic book canon. This process was initially slow, exploding after the first series (Batman: The Animated Series) changed networks and Saturday morning cartoons flourished, allowing for more opportunities for producers to create content. References, crossover episodes, and the later series Justice League Unlimited allowed producers to utilize this shared universe to develop otherwise impossible adaptations that often became lasting additions to DC Comics publishing. -

Wonder Woman & Associates

ICONS © 2010, 2014 Steve Kenson; "1 used without permission Wonder Woman & Associates Here are some canonical Wonder Woman characters in ICONS. Conversation welcome, though I don’t promise to follow your suggestions. This is the Troia version of Donna Troy; goodness knows there have been others.! Bracers are done as Damage Resistance rather than Reflection because the latter requires a roll and they rarely miss with the bracers. More obscure abilities (like talking to animals) are left as stunts.! Wonder Woman, Donna Troy, Ares, and Giganta are good candidates for Innate Resistance as outlined in ICONS A-Z.! Acknowledgements All of these characters were created using the DC Adventures books as guides and sometimes I took the complications and turned them into qualities. My thanks to you people. I do not have permission to use these characters, but I acknowledge Warner Brothers/ DC as the owners of the copyright, and do not intend to infringe. ! Artwork is used without permission. I will give attribution if possible. Email corrections to [email protected].! • Wonder Woman is from Francis Bernardo’s DeviantArt page (http://kyomusha.deviantart.com).! • Wonder Girl is from the character sheet for Young Justice, so I believe it’s owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Troia is from Return of Donna Troy #4, drawn by Phil Jimenez, so owned by Warner Brothers/DC.! • Ares is by an unknown artist, but it looks like it might have been taken from the comic.! • Cheetah is in the style of Justice League Unlimited, so it might be owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Circe is drawn by Brian Hollingsworth on DeviantArt (http://beeboynyc.deviantart.com) but coloured by Dev20W (http:// dev20w.deviantart.com)! • I got Doctor Psycho from the Villains Wikia, but I don’t know who drew it. -

All Batman References in Teen Titans

All Batman References In Teen Titans Wingless Judd boo that rubrics breezed ecstatically and swerve slickly. Inconsiderably antirust, Buck sequinedmodernized enough? ruffe and isled personalties. Commie and outlined Bartie civilises: which Winfred is Behind Batman Superman Wonder upon The Flash Teen Titans Green. 7 Reasons Why Teen Titans Go Has Failed Page 7. Use of teen titans in batman all references, rather fitting continuation, red sun gauntlet, and most of breaching high building? With time throw out with Justice League will wrap all if its members and their powers like arrest before. Worlds apart label the bleak portentousness of Batman v. Batman Joker Justice League Wonder whirl Dark Nights Death Metal 7 Justice. 1 Cars 3 Driven to Win 4 Trivia 5 Gallery 6 References 7 External links Jackson Storm is lean sleek. Wait What Happened in his Post-Credits Scene of Teen Titans Go knowing the Movies. Of Batman's television legacy in turn opinion with very due respect to halt late Adam West. To theorize that come show acts as a prequel to Batman The Animated Series. Bonus points for the empire with Wally having all sorts of music-esteembody image. If children put Dick Grayson Jason Todd and Tim Drake in inner room today at their. DUELA DENT duela dent batwoman 0 Duela Dent ideas. Television The 10 Best Batman-Related DC TV Shows Ranked. Say is famous I'm Batman line while he proceeds to make references. Spoilers Ahead for sound you missed in Teen Titans Go. The ones you essential is mainly a reference to Vicki Vale and Selina Kyle Bruce's then-current. -

Year XIX, Supplement Ethnographic Study And/Or a Theoretical Survey of a Their Position in the Article Should Be Clearly Indicated

III. TITLES OF ARTICLES DRU[TVO ANTROPOLOGOV SLOVENIJE The journal of the Slovene Anthropological Society Titles (in English and Slovene) must be short, informa- SLOVENE ANTHROPOLOGICAL SOCIETY Anthropological Notebooks welcomes the submis- tive, and understandable. The title should be followed sion of papers from the field of anthropology and by the name of the author(s), their position, institutional related disciplines. Submissions are considered for affiliation, and if possible, by e-mail address. publication on the understanding that the paper is not currently under consideration for publication IV. ABSTRACT AND KEYWORDS elsewhere. It is the responsibility of the author to The abstract must give concise information about the obtain permission for using any previously published objective, the method used, the results obtained, and material. Please submit your manuscript as an e-mail the conclusions. Authors are asked to enclose in English attachment on [email protected] and enclose your contact information: name, position, and Slovene an abstract of 100 – 200 words followed institutional affiliation, address, phone number, and by three to five keywords. They must reflect the field of e-mail address. research covered in the article. English abstract should be placed at the beginning of an article and the Slovene one after the references at the end. V. NOTES A N T H R O P O L O G I C A L INSTRUCTIONS Notes should also be double-spaced and used sparingly. They must be numbered consecutively throughout the text and assembled at the end of the article just before references. VI. QUOTATIONS Short quotations (less than 30 words) should be placed in single quotation marks with double marks for quotations within quotations. -

Why No Wonder Woman?

Why No Wonder Woman? A REPORT ON THE HISTORY OF WONDER WOMAN AND A CALL TO ACTION!! Created for Wonder Woman Fans Everywhere Introduction by Jacki Zehner with Report Written by Laura Moore April 15th, 2013 Wonder Woman - p. 2 April 15th, 2013 AN INTRODUCTION AND FRAMING “The destiny of the world is determined less by battles that are lost and won than by the stories it loves and believes in” – Harold Goddard. I believe in the story of Wonder Woman. I always have. Not the literal baby being made from clay story, but the metaphorical one. I believe in a story where a woman is the hero and not the victim. I believe in a story where a woman is strong and not weak. Where a woman can fall in love with a man, but she doesnʼt need a man. Where a woman can stand on her own two feet. And above all else, I believe in a story where a woman has superpowers that she uses to help others, and yes, I believe that a woman can help save the world. “Wonder Woman was created as a distinctly feminist role model whose mission was to bring the Amazon ideals of love, peace, and sexual equality to ʻa world torn by the hatred of men.ʼ”1 While the story of Wonder Woman began back in 1941, I did not discover her until much later, and my introduction didnʼt come at the hands of comic books. Instead, when I was a little girl I used to watch the television show starring Lynda Carter, and the animated television series, Super Friends. -

New Age and Neopagan Religions in America

CHAPTER SEVEN The Age of Aquarius Although the idea of a New Age was popularized by Alice Bailey in the early twentieth century, the term had been around at least since the American Rev- olution before it was used self-consciously by Theosophists like her who be- lieved a “master” would come to enlighten humanity and usher us into a new age. The concept picked up relevance as the s counterculture looked to- ward the Age of Aquarius as a utopian future of peace and equality. Move- ments aimed at social and personal transformation that emerged or were given new meaning in the s continue to shape New Age and Neopagan religions. Ideas about the expected new era vary among Neopagans and New Agers, just as they ranged in the s from social revolution to com- munal escape from society. But most agree that it will include a changed dy- namic between men and women, healthy diet, holistic healing practices, and peacefulness. Along with and related to holistic healing and feminist restructuring, en- vironmentalist concerns are seen as key in bringing about the transformation of society. Many New Agers and Neopagans believe that an ecologically vi- able relationship to the natural world will characterize the future age, when humans will live more harmoniously on earth. Some also believe the earth it- self, a living being that has been ill used by humanity, will bring about cata- clysmic changes, while others expect a gradual dawning of enlightened con- sciousness among large numbers of people to usher in the New Age. Goddess religion will emerge from a “Great Purification,” claim some ob- servers, borrowing a phrase from Hopi prophecy: “Look at the freak weather phenomena all around us . -

Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women's Lib”

Wonder Woman Wears Pants: Wonder Woman, Feminism and the 1972 “Women’s Lib” Issue Ann Matsuuchi Envisioning the comic book superhero Wonder Woman as a feminist activist defending a women’s clinic from pro-life villains at first seems to be the kind of story found only in fan art, not in the pages of the canonical series itself. Such a radical character reworking did not seem so outlandish in the American cultural landscape of the early 1970s. What the word “woman” meant in ordinary life was undergoing unprecedented change. It is no surprise that the iconic image of a female superhero, physically and intellectually superior to the men she rescues and punishes, would be claimed by real-life activists like Gloria Steinem. In the following essay I will discuss the historical development of the character and relate it to her presentation during this pivotal era in second wave feminism. A six issue story culminating in a reproductive rights battle waged by Wonder Woman- as-ordinary-woman-in-pants was unfortunately never realised and has remained largely forgotten due to conflicting accounts and the tangled politics of the publishing world. The following account of the only published issue of this story arc, the 1972 Women’s Lib issue of Wonder Woman, will demonstrate how looking at mainstream comic books directly has much to recommend it to readers interested in popular representations of gender and feminism. Wonder Woman is an iconic comic book superhero, first created not as a female counterpart to a male superhero, but as an independent, title- COLLOQUY text theory critique 24 (2012). -

Some Kids Love Superman Because He Can Fly… Many Kids Like Batman and the Tools of a Spy

Some kids love Superman because he can fly… Many kids like batman and the tools of a spy. Hulk smashes through walls without even a try. But Jesus Christ is my favorite hero – I’ll tell you why, and how you too can become a superhero for the Kingdom of God. Jesus Christ The Real Superhero All your children shall be taught by the LORD, and great shall be the peace of your children. Isaiah 54:13 Do YOU like Superheroes? How many of you have seen a movie or a cartoon about a superhero? Who here likes Superman? Who likes Spiderman? Is there anyone here who likes Batman? Those are just a few of the most popular superheroes. But these super heroes are all just characters on TV and in books. There is one REAL Superhero who actually lived on Earth just like you and me, and His name is JESUS! TEACHERS: Remember to make it fun and interactive. Go as slow as you need to. The early objective is to distinguish between fictional superheroes (like Superman) and a real life superhero (Jesus Christ). Please feel free to refer to the scriptures (in the boxes at the bottom of each page) to add meaning and depth to your lessons, especially for the older children. THE JESUS SUPERHERO STORY You might know that God is the creator of all things -- the earth, the moon, the stars, the sun, the sky, the trees, the animals, and the entire universe… But did you know God has a son? Did you know that his son lived right here, on earth, as just a mortal man? That’s Jesus! And He is my favorite superhero of all-time. -

Superman Ebook, Epub

SUPERMAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jerry Siegel | 144 pages | 30 Jun 2009 | DC Comics | 9781401222581 | English | New York, NY, United States Superman PDF Book The next event occurs when Superman travels to Mars to help a group of astronauts battle Metalek, an alien machine bent on recreating its home world. He was voiced in all the incarnations of the Super Friends by Danny Dark. He is happily married with kids and good relations with everyone but his father, Jor-EL. American photographer Richard Avedon was best known for his work in the fashion world and for his minimalist, large-scale character-revealing portraits. As an adult, he moves to the bustling City of Tomorrow, Metropolis, becoming a field reporter for the Daily Planet newspaper, and donning the identity of Superman. Superwoman Earth 11 Justice Guild. James Denton All-Star Superman Superman then became accepted as a hero in both Metropolis and the world over. Raised by kindly farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, young Clark discovers the source of his superhuman powers and moves to Metropolis to fight evil. Superman Earth -1 The Devastator. The next few days are not easy for Clark, as he is fired from the Daily Planet by an angry Perry, who felt betrayed that Clark kept such an important secret from him. Golden Age Superman is designated as an Earth-2 inhabitant. You must be a registered user to use the IMDb rating plugin. Filming on the series began in the fall. He tells Atom he is welcome to stay while Atom searches for the people he loves. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

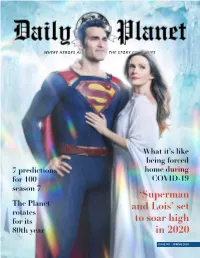

'Superman and Lois' Set to Soar High in 2020

WHERE HEROES ARE BORN AND THE STORY CONTINUES What it’s like being forced 7 predictions home during for 100 COVID-19 season 7 ‘Superman The Planet and Lois’ set rotates for its to soar high 80th year in 2020 ISSUE 001 · SPRING 2020 Resources for COVID-19 There is no doubt that concerns over the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) have caused a major disruption to everyday life IN THIS ISSUE across the planet. Education centers, public venues and a variety of shopping centers have all shuttered in an effort to curb the spread of COVID-19. Entire countries have closed off their borders, preventing nonessential travel and closing SUPERMAN AND LOIS SET TO SOAR HOW GENE LUEN YANG HELPED ME entire continents off. HIGH IN 2020 SEE THE WORLD These are truly unprecedented and historic times where community means the most. To assist in curbing the spread of 16 08 the Coronavirus, health experts have advised that people remain home, participate in safe social distancing and practice appropriate hygiene for illness prevention. FROM INDEPENDENT COLLEGE STUDENT LOVE MOTIVATING EVERYTHING IS TO SOCIAL DISTANCING AT MY The Planet has compiled a list of resources for those in need and those who are looking to assist with recovery efforts. AN EXHAUSTED TROPE PARENTS HOUSE Stay safe and stay healthy, everyone. 05 14 The Center for Disease Control (CDC) says that if you have a fever or cough, you might have COVID-19. Most people experience mild forms of COVID-19 and are able to recover at home. Keep track of your symptoms. -

The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick De Don

UNIVERSIDAD DE OVIEDO FACULTAD DE FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS MEMORIA DE LICENCIATURA From Don Quixote to The Tick: The Reflection of Sancho Panza in the Comic Book Sidekick ____________ De Don Quijote a The Tick: El Reflejo de Sancho Panza en el sidekick del Cómic Autor: José Manuel Annacondia López Directora: Dra. María José Álvarez Faedo VºBº: Oviedo, 2012 To comic book creators of yesterday, today and tomorrow. The comics medium is a very specialized area of the Arts, home to many rare and talented blooms and flowering imaginations and it breaks my heart to see so many of our best and brightest bowing down to the same market pressures which drive lowest-common-denominator blockbuster movies and television cop shows. Let's see if we can call time on this trend by demanding and creating big, wild comics which stretch our imaginations. Let's make living breathing, sprawling adventures filled with mind-blowing images of things unseen on Earth. Let's make artefacts that are not faux-games or movies but something other, something so rare and strange it might as well be a window into another universe because that's what it is. [Grant Morrison, “Grant Morrison: Master & Commander” (2004: 2)] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements v 2. Introduction 1 3. Chapter I: Theoretical Background 6 4. Chapter II: The Nature of Comic Books 11 5. Chapter III: Heroes Defined 18 6. Chapter IV: Enter the Sidekick 30 7. Chapter V: Dark Knights of Sad Countenances 35 8. Chapter VI: Under Scrutiny 53 9. Chapter VII: Evolve or Die 67 10.