Unit Development Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments

Adopt a Heritage Project - List of Adarsh Monuments Monument Mitras are invited under the Adopt a Heritage project for selecting/opting monuments from the below list of Adarsh Monuments under the protection of Archaeological Survey of India. As provided under the Adopta Heritage guidelines, a prospective Monument Mitra needs to opt for monuments under a package. i.e Green monument has to be accompanied with a monument from the Blue or Orange Category. For further details please refer to project guidelines at https://www.adoptaheritage.in/pdf/adopt-a-Heritage-Project-Guidelines.pdf Please put forth your EoI (Expression of Interest) for selected sites, as prescribed in the format available for download on the Adopt a Heritage website: https://adoptaheritage.in/ Sl.No Name of Monument Image Historical Information Category The Veerabhadra temple is in Lepakshi in the Anantapur district of the Indian state of Andhra Virabhadra Temple, Pradesh. Built in the 16th century, the architectural Lepakshi Dist. features of the temple are in the Vijayanagara style 1 Orange Anantpur, Andhra with profusion of carvings and paintings at almost Pradesh every exposed surface of the temple. It is one of the centrally protected monumemts of national importance. 1 | Page Nagarjunakonda is a historical town, now an island located near Nagarjuna Sagar in Guntur district of Nagarjunakonda, 2 the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, near the state Orange Andhra Pradesh border with Telangana. It is 160 km west of another important historic site Amaravati Stupa. Salihundam, a historically important Buddhist Bhuddist Remains, monument and a major tourist attraction is a village 3 Salihundum, Andhra lying on top of the hill on the south bank of the Orange Pradesh Vamsadhara River. -

February,2018 No.2 NEWS DIGEST VOL

Vol. XXXII February,2018 No.2 NEWS DIGEST VOL. XXXII No.2 February 2018 CONTNNTS PACES I KERALANEWS - 1- 10 II NAIIONAL NEWS - 11. - 21 ,.. NEWS FROMOTHEIT STATES ANI) "' ulttoN trnnltontrs 22_32 IV INTERNAI'IONAI, NI]WS . 33- 42 oc, 63.0Gor'l "o. "oftiLJ(rtJ" cd,ogdlcq6l e6. cauoccl0c(rt 4,6. oAr(o)08 oc(T)coo oc0J. oc(r)Joo oo@go st(o, s.0(go'l d(!Blai H. 'Ite Hindu P Tbe Pioneer N.I,E New Iridian Irxpress I.E. Indian Express T.O.r. The Times of India F,E, Financial llxprcss E.T, Economic Times S. The Statesman T. The l'elegraph oeoe aJoD' fiDofiUOC(I)OtC6(oro60a oo.dO(ID-,@d.s1.(r1)'l: 6rrlo(Rccn1(I)" aso dr(sce.s,l orc98cqgg @oo ps.aaDao'lo'los o6.6o@:6ro6.s1.ful.aQos ocsrD 6tccoc mreilooo d,so 6jo, cd:csl (rDor@locorDJgo gt^rRi ed,gloi. 5r)J.nigg o4,.ooau:lBDd.s1.mt.an.d B].!G.ru.n acsldo(m(o" 5000 6ffFd-. @o.Jr9o.olo .r)lEJg' ca)cd.gco4oioal @rso 5079.59 c6hcsl. @ra(occorao- Ogson 6rccoc 6tu(SJ.looo o,sc olocecsl @Lrsl" qo'gl.oE. (oc.,0U02\ .ogc{o @oDolcq oloFr(I)o(or'ls(o]d; aac@o Go(i6o1@1qo ocAJ.drD' olcq oenmlao6rDo nrjgoJo d,ostoo ae]fl dr(dto)mo(dn5. 26 (dro5rD' Groonso(.o) olcaQ g6yDartelorc@olanar. 60 oloo oUod,eal(d) eo6Uelo)c6ryr: ca,ogaoolol olcaQ npncD"l6@6mo o0g.{o SQ(6)(ll8 Og.olelc6n- (55). -

District Census Handbook, Pudukkottai, Part XII a & B, Series-23

CENSUS OF INDIA 1991 SERIES - 23 TAMIL NADU DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PUDUKKOlTAI PARTXII A&B VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE AND TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT K. SAMPATH KUMAR OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS TAMILNADU CONTENTS Pag,~ No. 1. Foreward (vii-ix) 2. Preface (xi-xv) 3. Di::'trict Map Facing Page .:;. Important Statistics 1-2 5. Analytical Note: I) Census concepts: Rural and Urban areas, Urban Agglomeration, Census House/Household, SC/ST, Literates, Main Workers, Marginal 3-4 Workers, Non-Workers etc. H) History of the District Census Handhook including scope of Village and Town Directory and Primary Census Abstract. 5-9 iii) History of the District and its Formation, Location and Physiography, Forestry, Flora and Fauna, Hills, Soil, Minerals and Mining, Rivers, EledricHy and Power, Land and Land use pattern, Agriculture and Plantations, Irrigation, Animal Husbandry, Fisheries, Industries, Trade and Commerce, Transpoli and Communications, Post and Telegraph, Rainfall, Climate and Temperature, Education, People, Temples and Places of Tourist Importance. lO-20 6. Brief analysis of the Village and Town Dirctory and Primary Census Abstract data. 21-41 PART-A VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY Section-I Village Directory 43 Note explaining the codes used in the Village Directory. 45 1. Kunnandarkoil C.D. Block 47 i) Alphabetical list of villages 48-49 ii) Village Directory Statement 50-55 2. Annavasal C.D. Block 57 i) Alphabetical list of villages 50-59 iil Village Directory Statement 60-67 3. Viralimalai C.D. Block 69 i) Alphabetical list of villages 70-71 iil Village Directory Statement 72-79 4. -

Tnpsc Group 2 & 2A Postal Test Series 2019

www.TNPSC.Academy TNPSC GROUP 2 & 2A POSTAL TEST SERIES 2019 TEST NO: 31 TOTAL QUESTIONS: 200 TIME: 3:00 Hrs MOCK TEST – 1 GENERAL STUDIES & GENERAL ENGLISH An Online TNPSC Academy for all your TNPSC Exam Preparations Group 1, Group 2 & 2A, Group 3, Group 4, VAO, TNUSRB and Others. SPACE FOR ROUGH WORK www.TNPSC.Academy Group 2 & 2A - 2019 Test Series | Test 31 – Mock Test 1 P a g e | 1 1. ______________ is a word or phrase that usually come Choose the correct ‘Synonyms’ for the underlined after a ‘be’ verb such as am, is, are, was and were to words from the options given make the sense complete. A) Verb B) Subject She was in a two-metre wide concrete storm drain C) Complement D) None of these which was almost completely filled with water and it was still rising. Across the drain stretched a small 2. Name the goddess which mention in the prose “To the plastic pipe. Further on, the tunnel was completely land of snow”. black. A) Nanda devi B) parvathi C) laxmi D) durga 10. CONCRETE A) Real B) Unreal 3. Who is the poet of “The Piano”? C) Set D) None of them A) Famida Y. Basheer B) Lewis Carroll C) Kamala Das D) D.H. Lawrence 11. COMPLETELY A) Utterly B) Unruly 4. Match the following C) Untidy D) All of them A) Khalil Gibran 1883-1931 B) Annie Louisa walker 1836-1907 12. RISING C) D.H.Lawrence 1885-1930 A) Volume down B) Expanding D) Walt Whitman 1819-1892 C) Ruled D) Extra A) 1 2 3 4 B) 2 3 4 1 13. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2017 [Price: Rs. 16.80 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 35] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 30, 2017 Aavani 14, Hevilambi, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2048 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages. Change of Names .. 1891-1931 Notice .. 1932 Notice .. 682-685 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 27216. My son, X.A Binto Bestley, born on 22nd July 2002 27219. I, Nallathambi, son of Thiru Chellaiya, born on (native district: Kanyakumari), residing at No. 3/2B-1C, 20th May 1980 (native district: Madurai), residing at Johan Street, Kuthankadu, Konam, Nagercoil, Kanyakumari Old No. 3/3A, New No. 3/55A, Muniyandikovil Street, Kallikudi, District, shall henceforth be known as A BESTLEY Madurai-625 402, shall henceforth be known as C. RAMESH A. AMTHAN ï™ôî‹H Kanyakumari, 21st August 2017. (Father) Madurai, 21st August 2017. 27217. I, M.Jaya, wife of Thiru L. Malaichsamy, born on 27220. My daughter, R.A. Meera Reddy, born on 28th March 2013 (native district: Madurai), residing at 1st January 1986 (native district: Madurai), residing at No. 58/59, Flat-E, Sree Chaitanya Apartment, New Kumaran No. 3-121, Saranthaangi, Vellayapatti, Vadipatti Taluk, Nagar, 1st Main Road, Sholinganallur, Chennai-600 119, Madurai-625 503, shall henceforth be known as M. -

Later Mural Traditions

5 LATER MURAL TRADITIONS VEN after Ajanta, very few sites with paintings have Esurvived which provide valuable evidences to reconstruct the tradition of paintings. It may also be noted that the sculptures too were plastered and painted. The tradition of cave excavations continued further at many places where sculpting and painting were done simultaneously. Badami One such site is Badami in the State of Karnataka. Badami was the capital of the early Chalukyan dynasty which ruled Queen and the region from 543 to 598 CE. With the attendants, Badami decline of the Vakataka rule, the Chalukyas established their power in the Deccan. The Chalukya king, Mangalesha, patronised the excavation of the Badami caves. He was the younger son of the Chalukya king, Pulakesi I, and the brother of Kirtivarman I. The inscription in Cave No.4 mentions the date 578–579 CE, describes the beauty of the cave and includes the dedication of the image of Vishnu. Thus it may be presumed that the cave was excavated in the same era and the patron records his Vaishnava affiliation. Therefore, the cave is popularly known as the Vishnu Cave. Only a fragment of the painting has survived on the vaulted roof of the front mandapa. Paintings in this cave depict palace scenes. One shows Kirtivarman, the son of Pulakesi I and the elder brother of Mangalesha, seated inside the palace with his wife and feudatories watching a dance scene. Towards the corner of the panel are figures of Indra and his retinue. Stylistically speaking, the painting represents an 2021-22 62 AN INTRODUCTION TO INDIAN ART extension of the tradition of mural painting from Ajanta to Badami in South India. -

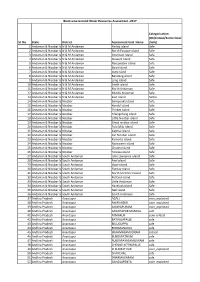

Sl. No State District Assessment Unit Name Categorization (OE/Critical

Block wise Ground Water Resources Assessment -2017 Categorization (OE/Critical/Semicritical Sl. -

![6Th Social Science 2Nd Term Additional Questions [New Book]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7482/6th-social-science-2nd-term-additional-questions-new-book-8997482.webp)

6Th Social Science 2Nd Term Additional Questions [New Book]

Social Science Prepared By www.winmeen.com 6th Social Science 2nd Term Additional Questions [New Book] History Unit -1 Vedic Culture in North India and Megalithic Culture in South India I. Choose the correct answer: 1. The first phase of urbanization in India to an end with the decline of _________ a) Indus civilization b) Vedic civilization c) Bronze civilization d) none of the above. 2. The main source of wealth in the Rig Vedic period was _______ a) Land b) Gold coins c) Cattle d) Rice 3. Sapta Sindhu means the land of _______ a) seven rivers b) seven villages c) seven tribes d) seven hills. 4. Vishayapati was the head of a ________ a) rashtra b) village c) clan d) jana 5. IN economic, political and military matters, the king was assisted by the ________ a) Gramani b) Senani c) Purohit d) Vidhaa 6. Non-Aryans were called ________ a) Janas b) Dasyus c) Sabha d) Samitha 7. IN the Latter Vedic Period the role of women in society ________ a) increased b) declined c) remained the same as before d) became equal with the role of man. Learning Leads To Ruling Page 1 of 34 Social Science Prepared By www.winmeen.com 8. The Staple crop of the Aryans was ___________ a) Rice b) Wheat c) Millets d) Barley 9. Patympalli is located in _________ dristirct. a) Vellore b) Madurai c) Sivaganga d) Dindital II. Match the statement with the Reasons. Tick the appropriate answer: 1. Statement (A): The megalithic monuments bear witness to a highly advanced state of civilization with the knowledge of iron and community living. -

1 Central Chhattisgarh Raigarh Raigad Fort CLOSED 2 Central

Opening Status S.No. Zone State/UT City Monument/Sites Remarks (OPEN/CLOSED) 1 Central Chhattisgarh Raigarh Raigad Fort CLOSED 2 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Bhimbetka (Rock Painting) CLOSED 3 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Birla Museum CLOSED 4 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Monuments Of Islam Nagar CLOSED 5 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Museum Of Man CLOSED 6 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Sanchi Museum CLOSED 7 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Sanchi Stupa CLOSED 8 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal State Archealogical Museum CLOSED 9 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Udaigiri Caves (Near Vidisha) CLOSED 10 Central Madhya Pradesh Bhopal Ujjain Temples CLOSED 11 Central Madhya Pradesh Datia Datia Fort CLOSED 12 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Archaeological Museum, Gwalior CLOSED 13 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Gujri Mahal CLOSED 14 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Gwalior Fort CLOSED 15 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Mohammad Ghaus Tomb CLOSED 16 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Scindia Museum (Jai Vilas Palace Museum) CLOSED 17 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Tansen Tomb CLOSED 18 Central Madhya Pradesh Gwalior Teli Mandir CLOSED 19 Central Madhya Pradesh Indore Hoshang Shahs Tomb CLOSED 20 Central Madhya Pradesh Indore Temples CLOSED 21 Central Madhya Pradesh Jabalpur Marble Rocks & Bhedaghat CLOSED 22 Central Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho Archaeological Museum CLOSED 23 Central Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho Khajuraho Temples CLOSED 24 Central Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho Pandav Fall CLOSED 25 Central Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho Panna Daimond Mines CLOSED 26 Central -

Sl. No State District Assessment Unit Name Categorization (Over

Block wise Ground Water Resource Assessment-2020 Categorization (Over-Exploited/ Assessment Unit Sl. No State District Critical/ Name SemiCritical/ Safe/Saline) Andaman & Nicobar 1 N & M Andaman AVES ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 2 N & M Andaman BARATANG ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 3 N & M Andaman EAST ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 4 N & M Andaman INTERVIEW ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 5 N & M Andaman LONG ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 6 N & M Andaman MIDDLE ANDAMAN Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 7 N & M Andaman NARCONDAM ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 8 N & M Andaman NORTH ANDAMAN Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar NORTH PASSAGE 9 N & M Andaman Safe Islands ISLAND Andaman & Nicobar 10 N & M Andaman PROLOB ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 11 N & M Andaman SMITH ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 12 N & M Andaman STEWART ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 13 N & M Andaman STRAIT ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 14 Nicobar BOMPOOKA ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 15 Nicobar CAR NICOBAR ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 16 Nicobar CHOWRA ISLAND Saline Islands Andaman & Nicobar GREAT NICOBAR 17 Nicobar Safe Islands ISLAND Andaman & Nicobar 18 Nicobar KAMORTA ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 19 Nicobar KATCHAL ISLAND Safe Islands Andaman & Nicobar 20 Nicobar KONDUL ISLAND Safe Islands Block wise Ground Water Resource Assessment-2020 Categorization (Over-Exploited/ Assessment Unit Sl. No State District Critical/ Name SemiCritical/ Safe/Saline) Andaman & Nicobar LITTLE -

Art and Culture ( Supplementary Material )

https://t.me/UPSC_PDF www.UPSCPDF.com https://t.me/UPSC_PDF VISION IAS ™ www.visionias.in www.visionias.wordpress.com ART AND CULTURE ( SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL ) Copyright © by Vision IAS All rights are reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of Vision IAS www.visionias.in ©Vision IAS Download from:- www.UPSCPDF.com https://t.me/UPSC_PDF www.UPSCPDF.com https://t.me/UPSC_PDF Student Notes: ART AND CULTURE – SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Contents 1] Architecture and Sculpture ........................................................................................................ 4 2] Classification of India Architecture ............................................................................................ 4 3] Harappan Civilization (Indus Valley Civilization) Art .................................................................. 5 3.1 Seals ..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.2 Sculpture .............................................................................................................................. 5 3.3 Terracotta ............................................................................................................................. 6 3.4 Pottery ................................................................................................................................. -

Aschwin Lippe Collection

Aschwin Lippe Collection Dr. Elizabeth Graves 2017 Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives Washington, D.C. 20013 [email protected] https://www.freersackler.si.edu/research/archives/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Personal and Professional Life................................................................. 4 Series 2: Correspondence...................................................................................... 12 Series 3: East Asia: Research and Publications.................................................... 18 Series 4: India Research and Publications............................................................ 22 Series 5: Photography...........................................................................................