Atlantic Rock Crab, Jonah Crab Canada Atlantic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

68 Guide to Crustacea

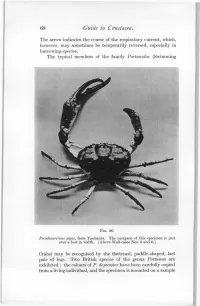

68 Guide to Crustacea. The arrow indicates the course of the respiratory current, which, however, may sometimes be temporarily reversed, especially in burrowing species. The typical members of the family Portunidae (Swimming FIG. 46. Pseudocarcinus gigas, from Tasmania. The carapace of this specimen is just over a foot in width. [Above Wall-cases Nos. 5 and 6.] Crabs) may be recognised by the flattened, paddle-shaped, last pair of legs. Two British species of the genus Portunus are exhibited : the colours of P. depurator have been carefully copied from a living individual, and the specimen is mounted on a sample Decapoda—Brachyura. 69 of the shell-gravel on which it was actually caught. The large Neptunus pelagicus is the commonest edible Crab in many parts of the East. The Common Shore Crab, Carcinus maenas, is also referred to this family, although the paddle-shape of the last legs is not so marked as in the more typical Portunidae. Podophthalmus vigil (Fig. 47) is remarkable for the great length of the eye-stalks, which is quite unusual among the Cyclometopa, and gives this Crab a curious likeness to the genus Macrophthalmus among the Ocypodidae (see Table-case No. 16). The resemblance, however, is quite superficial, for in this case FIG. 47. Podophthalmus vigil (reduced). [Table-case No. 15.] it is the first of the two segments of the eye-stalk which is elongated, while in Macrophthalmus it is the second. The genus Platyonychus, of which a group of specimens is mounted in Wall-case No. 5, also belongs to this family. -

Northern Wolffish,Anarhichas Denticulatus

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Northern Wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada THREATENED 2012 COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Northern Wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 41 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm) Previous report(s): COSEWIC. 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 21 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm) O’Dea, N.R., and R.L. Haedrich. 2001. COSEWIC status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and status report on the northern wolffish Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-21 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Red Méthot for writing the status report on the Northern Wolffish, Anarhichas denticulatus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. The report was overseen and edited by John Reynolds, COSEWIC Marine Fishes Specialist Subcommittee Co-chair. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: 819-953-3215 Fax: 819-994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Loup à tête large (Anarhichas denticulatus) au Canada. -

Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean Volume

ISBN 0-9689167-4-x Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean (Davis Strait, Southern Greenland and Flemish Cap to Cape Hatteras) Volume One Acipenseriformes through Syngnathiformes Michael P. Fahay ii Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean iii Dedication This monograph is dedicated to those highly skilled larval fish illustrators whose talents and efforts have greatly facilitated the study of fish ontogeny. The works of many of those fine illustrators grace these pages. iv Early Stages of Fishes in the Western North Atlantic Ocean v Preface The contents of this monograph are a revision and update of an earlier atlas describing the eggs and larvae of western Atlantic marine fishes occurring between the Scotian Shelf and Cape Hatteras, North Carolina (Fahay, 1983). The three-fold increase in the total num- ber of species covered in the current compilation is the result of both a larger study area and a recent increase in published ontogenetic studies of fishes by many authors and students of the morphology of early stages of marine fishes. It is a tribute to the efforts of those authors that the ontogeny of greater than 70% of species known from the western North Atlantic Ocean is now well described. Michael Fahay 241 Sabino Road West Bath, Maine 04530 U.S.A. vi Acknowledgements I greatly appreciate the help provided by a number of very knowledgeable friends and colleagues dur- ing the preparation of this monograph. Jon Hare undertook a painstakingly critical review of the entire monograph, corrected omissions, inconsistencies, and errors of fact, and made suggestions which markedly improved its organization and presentation. -

Seasonal Movements and Distribution of Dungeness Crabs Cancer Magister in a Glacial Southeastern Alaska Estuary

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 214: 167–176, 2001 Published April 26 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Seasonal movements and distribution of Dungeness crabs Cancer magister in a glacial southeastern Alaska estuary Robert P. Stone*, Charles E. O’Clair Auke Bay Laboratory, Alaska Fisheries Science Center, National Marine Fisheries Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 11305 Glacier Highway, Juneau, Alaska 99801, USA ABSTRACT: The movements of 10 female and 8 male adult Dungeness crabs, Cancer magister (Dana, 1852), were monitored biweekly to monthly with ultrasonic biotelemetry for periods ranging from 73 to 555 d. Female and male crabs had different seasonal patterns of habitat use, depth distri- bution, and activity. The general pattern for female crabs was: (1) a relatively inactive period between November and mid-April at depths below 20 m; ovigerous crabs were typically buried dur- ing this period in a dense aggregation; (2) abrupt movement into shallow water (<8 m) in late April and residence there until early June; this movement was coincident with the spring phytoplankton bloom and initiation of larval hatching; (3) increased activity beginning in July with movement back to deeper water, presumably to forage. Females that molted prior to oviposition did so in June and July. Male crabs occupied deep water (>40 m) from November to April, then concentrated in shallow water (<25 m), segregated from females, until late July. Males were most active in late summer and moved into deeper water (>30 m) near the mouth of the cove in fall. The range of depths were –0.5 to –61.3 m for females and +0.1 to –89.0 m for males. -

Dungeness Crab (Cancer Magister) Fishery

STATE OF WASHINGTON December 2008 Management Recommendations for Washington’s Priority Habitats and Species Dungeness Crab illustration courtesy of California Department of Fish and Game Dungeness Crab Cancer magister By Wendy Fisher and Donald Velasquez Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE GENERAL RANGE AND WASHINGTON DISTRIBUTION Dungeness Crabs (Cancer magister) are found in the coastal marine and estuarine waters of the northeastern Pacific Ocean from the Pribilof Islands, Alaska, to Santa Barbara, California (Jensen 1995). In Washington, Dungeness Crabs live in all marine waters, bays, and estuaries, including Willapa Bay, Grays Harbor, and Puget Sound (Figure 1). Within Puget Sound, they are most abundant in the waters north of Seattle, somewhat abundant in Hood Canal, and much less abundant in southern Puget Sound (Bumgarner 1990). RATIONALE The ecological requirements of Dungeness Crabs make them vulnerable to decline. This species is more susceptible to population impacts from harvest, disease, and dredging in areas where it concentrates for mating and egg incubation. It is also susceptible to mortality when caught in derelict fishing Figure 1. Washington’s distribution of gear (e.g., lost or abandoned crab pots and gillnets). Dungeness Crab. Dungeness Crab is included as a priority species in Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (WDFW’s) Priority Habitats and Species List (PHS List). They are an important resource for recreational, commercial and tribal harvests. Co-managed by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and Washington’s Treaty Tribes, Washington’s commercial harvest ranked first among all Pacific states and provinces between 2000 and 2004 (Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission data). -

Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-17-2017 Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality Brian Christopher Turner Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turner, Brian Christopher, "Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality" (2017). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3620. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5512 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Responses of Aquatic Non-Native Species to Novel Predator Cues and Increased Mortality by Brian Christopher Turner A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Environmental Sciences and Resources Dissertation Committee: Catherine E. de Rivera, Chair Edwin D. Grosholz Michael T. Murphy Greg M. Ruiz Ian R. Waite Portland State University 2017 Abstract Lethal biotic interactions strongly influence the potential for aquatic non-native species to establish and endure in habitats to which they are introduced. Predators in the recipient area, including native and previously established non-native predators, can prevent establishment, limit habitat use, and reduce abundance of non-native species. Management efforts by humans using methods designed to cause mass mortality (e.g., trapping, biocide applications) can reduce or eradicate non-native populations. -

Distribution, Abundance, and Diversity of Epifaunal Benthic Organisms in Alitak and Ugak Bays, Kodiak Island, Alaska

DISTRIBUTION, ABUNDANCE, AND DIVERSITY OF EPIFAUNAL BENTHIC ORGANISMS IN ALITAK AND UGAK BAYS, KODIAK ISLAND, ALASKA by Howard M. Feder and Stephen C. Jewett Institute of Marine Science University of Alaska Fairbanks, Alaska 99701 Final Report Outer Continental Shelf Environmental Assessment Program Research Unit 517 October 1977 279 We thank the following for assistance during this study: the crew of the MV Big Valley; Pete Jackson and James Blackburn of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Kodiak, for their assistance in a cooperative benthic trawl study; and University of Alaska Institute of Marine Science personnel Rosemary Hobson for assistance in data processing, Max Hoberg for shipboard assistance, and Nora Foster for taxonomic assistance. This study was funded by the Bureau of Land Management, Department of the Interior, through an interagency agreement with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Department of Commerce, as part of the Alaska Outer Continental Shelf Environment Assessment Program (OCSEAP). SUMMARY OF OBJECTIVES, CONCLUSIONS, AND IMPLICATIONS WITH RESPECT TO OCS OIL AND GAS DEVELOPMENT Little is known about the biology of the invertebrate components of the shallow, nearshore benthos of the bays of Kodiak Island, and yet these components may be the ones most significantly affected by the impact of oil derived from offshore petroleum operations. Baseline information on species composition is essential before industrial activities take place in waters adjacent to Kodiak Island. It was the intent of this investigation to collect information on the composition, distribution, and biology of the epifaunal invertebrate components of two bays of Kodiak Island. The specific objectives of this study were: 1) A qualitative inventory of dominant benthic invertebrate epifaunal species within two study sites (Alitak and Ugak bays). -

Feeding Habits of Wolffishes (Anarhichas Denticulatus, A. Lupus, A

NOT TO BE CITED WITHOUT PRIOR REFERENCE TO THE AUTHOR(S) Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Serial No. N5284 NAFO SCR Doc. 06/52 SCIENTIFIC COUNCIL MEETING – SEPTEMBER 2006 Feeding Habits of Wolffishes (Anarhichas denticulatus, A. lupus, A. minor) in the North Atlantic Concepción González (1), Xabier Paz, Esther Román and M. Alvárez Centro Oceanográfico de Vigo (I. E. O.) P O. Box 1552. 36280 Vigo. Spain. (1) [email protected] Abstract Feeding habits of 7 995 individuals of three wolffish species distributed in the north Atlantic were analyzed: 1 016 of northern wolffish (Anarhichas denticulatus), 4 783 of Atlantic wolffish (A. lupus) and 2 196 of spotted wolffish (A. minor). The individuals sampled were taken in the NAFO Area Divisions 3NO in spring in the period 2002- 2005, Div. 3L in summer in the period 2003-2004, Div. 3M in summer in the period 1993-2005, and in the ICES Area Div. IIb in autumn in the period 2004-2005. Feeding intensity was higher in the NAFO Area than in the northeast Atlantic (spring-summer vs. autumn), mainly in spotted wolffish in Div. 3M. The importance of each prey taxa was evaluated using the weight percentage. Wolffish species diet showed geographical differences. Ontogenic diet changes and prey variation throughout the studied period were observed, mainly in Atlantic and spotted wolffishes. This two species preyed primarily on bottom (echinoderms, gastropods and bivalves) and benthopelagic (northern shrimp and redfish) organisms on Flemish Cap and Grand Bank. However fish and northern shrimp predation were more important on the Flemish Cap, mainly in spotted wolffish, showing periods with higher predation on these prey when the biomass of these prey species increased. -

Atlantic Rock Crab, Jonah Crab US Atlantic

Atlantic rock crab, Jonah crab Cancer irroratus, Cancer borealis Image ©Scandinavian Fishing Yearbook / www.scandfish.com US Atlantic Trap May 12, 2016 Gabriela Bradt, Consulting researcher Neosha Kashef, Consulting Researcher Sam Wilding, Seafood Watch Senior Fisheries Scientist Disclaimer: Seafood Watch® strives to have all Seafood Reports reviewed for accuracy and completeness by external scientists with expertise in ecology, fisheries science and aquaculture. Scientific review, however, does not constitute an endorsement of the Seafood Watch® program or its recommendations on the part of the reviewing scientists. Seafood Watch® is solely responsible for the conclusions reached in this report. 2 Table of Contents About Seafood Watch® ................................................................................................................................. 3 Guiding Principles ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Assessment ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Criterion 1: Impact on the Species Under -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Chapter 3l Alaska Arctic Marine Fish Species Structure of Species Accounts……………………………………………………....2 Northern Wolffish…………………………………………………………………10 Bering Wolffish……………………………………………………………………14 Prowfish……………………………………………………………………………19 Arctic Sand Lance…………………………………………………………………24 Chapter 3. Alaska Arctic Marine Fish Species Accounts By Milton S. Love1, Nancy Elder2, Catherine W. Mecklenburg3, Lyman K. Thorsteinson2, and T. Anthony Mecklenburg4 Abstract Although tailored to address the specific needs of BOEM Alaska OCS Region NEPA analysts, the information presented Species accounts provide brief, but thorough descriptions in each species account also is meant to be useful to other about what is known, and not known, about the natural life users including state and Federal fisheries managers and histories and functional roles of marine fishes in the Arctic scientists, commercial and subsistence resource communities, marine ecosystem. Information about human influences on and Arctic residents. Readers interested in obtaining additional traditional names and resource use and availability is limited, information about the taxonomy and identification of marine but what information is available provides important insights Arctic fishes are encouraged to consult theFishes of Alaska about marine ecosystem status and condition, seasonal patterns (Mecklenburg and others, 2002) and Pacific Arctic Marine of fish habitat use, and community resilience. This linkage has Fishes (Mecklenburg and others, 2016). By design, the species received limited scientific attention and information is best accounts enhance and complement information presented in for marine species occupying inshore and freshwater habitats. the Fishes of Alaska with more detailed attention to biological Some species, especially the salmonids and coregonids, are and ecological aspects of each species’ natural history important in subsistence fisheries and have traditional values and, as necessary, updated information on taxonomy and related to sustenance, kinship, and barter. -

Re-Evaluation of the Cancridae Latreille, 1802 (Decapoda: Brachyura) Including Three New Genera and Three New Species 4 Carrie E

WW L^^ii»~^i • **«^«' s^f J-CLI//^/*IP / +' IU ! U~~> O' S~*Af/^i Contributions to Zoology, 69 (4) 223-250 (2000) SPB Academic Publishing hv. The Hague Re-evaluation of the Cancridae Latreille, 1802 (Decapoda: Brachyura) including three new genera and three new species 4 Carrie E. Schweitzer & Rodney M. Feldmann Department of Geology, Kent State University, Kent, Ohio 44242 U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected]. edit and [email protected] Keywords: Decapoda, Brachyura, Cancridae, Tertiary, paleobiogeography, Tethys Abstract Metacarcinus A. Milne Edwards, 1862 235 Metacarcinus goederti new species 236 New fossils referrable to the Cancridae Latreille, 1802 extend Notocarcinus new genus 239 the known stratigraphic range of the family into the middle Eocene Notocarcinus sulcatus new species 240 and the geographic range into South America. Each genus within Platepistoma Rathbun, 1906 241 the family has been reevaluated within the context of the new Romaleon Gistl, 1848 242 material. A suite of diagnostic characters for each cancrid ge Subfamily Lobocarcininae Beurlen, 1930 243 nus makes it possible to assign both extant and fossil speci Lobocarcinus Reuss, 1867 243 mens to genera and the two cancrid subfamilies, the Cancrinae Miocyclus Miiller, 1979 244 Latreille, 1802, and Lobocarcininae Beurlen, 1930, based solely Tasadia Miiller in Janssen and Miiller, 1984 244 upon dorsal carapace morphology. Cheliped morphology is useful Discussion 245 in assigning genera to the family but is significantly less useful Acknowledgements 246 at the subfamily and generic level. Each of the four subgenera References 246 sensu Nations (1975), Cancer Linnaeus, 1758, Glebocarcinus Appendix A 249 Nations, 1975, Metacarcinus A. -

Table of Contents

NEWFOUNDLAND ORPHAN BASIN EXPLORATION DRILLING PROGRAM Table of Contents 8.0 ASSESSMENT OF POTENTIAL EFFECTS ON MARINE FISH AND FISH HABITAT .....................................................................................................................8.1 8.1 Scope of Assessment ...................................................................................................8.1 8.1.1 Regulatory and Policy Setting ..................................................................... 8.1 8.1.2 Influence of Consultation and Engagement on the Assessment .................. 8.2 8.1.3 Potential Effects, Pathways and Measurable Parameters ........................... 8.2 8.1.4 Boundaries .................................................................................................. 8.4 8.1.4.1 Spatial Boundaries ..................................................................... 8.4 8.1.4.2 Temporal Boundaries ................................................................. 8.6 8.1.5 Residual Effects Characterization ............................................................... 8.6 8.2 Project Interactions with Marine Fish and Fish Habitat .................................................8.8 8.3 Assessment of Residual Environmental Effects on Marine Fish and Fish Habitat ......... 8.9 8.3.1 Project Pathways ...................................................................................... 8.10 8.3.2 Mitigation................................................................................................... 8.11 8.3.3 Characterization