'Threatened' Nigerian Leafy Vegetable, Gnetum Africanum (WILW)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Further Interpretation of Wodehouseia Spinata Stanley from the Late Maastrichtian of the Far East (China) M

ISSN 0031-0301, Paleontological Journal, 2019, Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 203–213. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2019. Russian Text © M.V. Tekleva, S.V. Polevova, E.V. Bugdaeva, V.S. Markevich, Sun Ge, 2019, published in Paleontologicheskii Zhurnal, 2019, No. 2, pp. 94–105. Further Interpretation of Wodehouseia spinata Stanley from the Late Maastrichtian of the Far East (China) M. V. Teklevaa, *, S. V. Polevovab, E. V. Bugdaevac, V. S. Markevichc, and Sun Ged aBorissiak Paleontological Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, 117647 Russia bMoscow State University, Moscow, 119991 Russia cFederal Scientific Center of the East Asia Terrestrial Biodiversity, Vladivostok, 690022 Russia dCollege of Paleontology, Shenyang Normal University, Shenyang, Liaoning Province, China *e-mail: [email protected] Received May 25, 2018; revised September 30, 2018; accepted October 15, 2018 Abstract—Dispersed pollen grains Wodehouseia spinata Stanley of unknown botanical affinity from the Maastrichtian of the Amur River Region, Far East are studied using transmitted light, scanning and trans- mission electron microscopy. The pollen was probably produced by wetland or aquatic plants, adapted to a sudden change in the water regime during the vegetation season. The pattern of the exine sculpture and spo- roderm ultrastructure suggests that insects contributed to pollination. The flange and unevenly thickened endexine could facilitate harmomegathy. A tetragonal or rhomboidal tetrad type seems to be most logical for Wodehouseia pollen. The infratectum structure suggests that Wodehouseia should be placed within an advanced group of eudicots. Keywords: Wodehouseia, exine morphology, sporoderm ultrastructure, “oculata” group, Maastrichtian DOI: 10.1134/S0031030119020126 INTRODUCTION that has lost its flange (see a review Wiggins, 1976). -

Seed Plant Phylogeny: Demise of the Anthophyte Hypothesis? Michael J

bb10c06.qxd 02/29/2000 04:18 Page R106 R106 Dispatch Seed plant phylogeny: Demise of the anthophyte hypothesis? Michael J. Donoghue* and James A. Doyle† Recent molecular phylogenetic studies indicate, The first suggestions that Gnetales are related to surprisingly, that Gnetales are related to conifers, or angiosperms were based on several obvious morphological even derived from them, and that no other extant seed similarities — vessels in the wood, net-veined leaves in plants are closely related to angiosperms. Are these Gnetum, and reproductive organs made up of simple, results believable? Is this a clash between molecules unisexual, flower-like structures, which some considered and morphology? evolutionary precursors of the flowers of wind-pollinated Amentiferae, but others viewed as being reduced from Addresses: *Harvard University Herbaria, 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, USA. †Section of Evolution and more complex flowers in the common ancestor of Ecology, University of California, Davis, California 95616, USA. angiosperms, Gnetales and Mesozoic Bennettitales [1]. E-mail: [email protected] These ideas went into eclipse with evidence that simple [email protected] flowers really are a derived, rather than primitive, feature Current Biology 2000, 10:R106–R109 of the Amentiferae, and that vessels arose independently in angiosperms and Gnetales. Vessels in angiosperms 0960-9822/00/$ – see front matter seem derived from tracheids with scalariform pits, whereas © 2000 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. in Gnetales they resemble tracheids with circular bor- dered pits, as in conifers. Gnetales are also like conifers in These are exciting times for those interested in plant lacking scalariform pitting in the primary xylem, and in evolution. -

On the Evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan Region: a Summary

The Palaeobotanist 57(2008) : 453-457 0031-0174/2008 $2.00 On the evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan region: A summary J.S. GULERIA Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, 53 University Road, Lucknow 226007, India. [email protected] (Received 10 June, 2007; revised version accepted 15 September, 2008) ABSTRACT Guleria JS 2008. On the evolution of Angiosperms in the Himalayan region: A summary. The Palaeobotanist 57(3): 453-457. The paper summarises the evolution of angiosperms in different zones of Himalaya. The Himalayan Cenozoic flora has been divided age-wise as Palaeogene and Neogene flora. The Himalayan Palaeogene flora is largely a continuation of tropical peninsular flora of India. The early Miocene flora of Lesser Himalaya is also moist tropical. However, temperate plants started appearing during Miocene in the Higher Himalaya and their occurrence in Plio-Pleistocene flora of Kashmir reflect uplift of the Himalaya. The sub-Himalayan flora indicates existence of warm humid conditions in this belt which became drier by the end of Pliocene. The northern floral elements appeared to have invaded India all along the Himalayan belt. Since its birth the Himalaya has played a significant role in the immigration of plants from the adjoining regions, i.e. east, west and north, thereby enriching the Indian flora. The development of the Cenozoic flora of the Himalayan region is an expression of changing patterns of geography, topography and climate. Key-words—Cenozoic, Angiosperms, Himalayan flora, Migration, Climate (India). fgeky;h -

Assessment of Nutritional Composition of Wild Vegetables Consumed by the People of Lebialem Highlands, South Western Cameroon

Food and Nutrition Sciences, 2017, 8, 647-657 http://www.scirp.org/journal/fns ISSN Online: 2157-9458 ISSN Print: 2157-944X Assessment of Nutritional Composition of Wild Vegetables Consumed by the People of Lebialem Highlands, South Western Cameroon Afui Mathias Mih*, Abwe Mercy Ngone, Lawrence Monah Ndam Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon How to cite this paper: Mih, A.M., Ngone, Abstract A.M. and Ndam, L.M. (2017) Assessment of Nutritional Composition of Wild Vege- Wild vegetables contribute immensely to the culinary basket and livelihoods tables Consumed by the People of Lebialem of rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa, especially among the people of Highlands, South Western Cameroon. Food Lebialem highlands of south western Cameroon where at least 26 such species and Nutrition Sciences, 8, 647-657. are consumed as vegetables. To promote the consumption of these vegetables, https://doi.org/10.4236/fns.2017.86046 the nutritional quality of five preferred species in this area, Amaranthus du- Received: May 19, 2017 bius Mart. Ex Thell., Gnetum africanum Welw., Lomariopsis guineensis (Un- Accepted: June 25, 2017 erw.) Alston, Pennisetum purpureum Schumach and Vernonia amygdalina Published: June 28, 2017 Del., was assessed using standard methods. L. guineensis had the highest car- Copyright © 2017 by authors and bohydrate, protein, calorific value and ash content, and the lowest fat content Scientific Research Publishing Inc. of 4.05%, very rich in K, Ca and Mg and the amino acids leucine, arginine, ly- This work is licensed under the Creative sine, phenylalanine and histidine. The amino acid content was generally Commons Attribution International higher than 25 mg/100g. -

Effect of Ethanol Leaf Extract of Gnetum Africanum on Testosterone and Oestradiol Induced Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

Vol. 14(7), pp. 309-316, July, 2020 DOI: 10.5897/JMPR2019.6901 Article Number: 3BA1CF663831 ISSN 1996-0875 Copyright © 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Medicinal Plants Research http://www.academicjournals.org/JMPR Full Length Research Paper Effect of ethanol leaf extract of Gnetum africanum on testosterone and oestradiol induced benign prostatic hyperplasia EBENYI Lilian N.1*, YONGABI Kenneth A.1,2, ALI Fredrick U.1, OMINYI Mathias C1, ANYANWU Blessing1 and OGBANSHI Moses E.3 1Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Science, Ebonyi State University, P. M. B. 043, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. 2Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, Imo State University, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. 3Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Ebonyi State University, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria. Received 28 December, 2019; Accepted 14 April, 2020 The effect of ethanol leaf extract of Gnetum africanum was studied in albino rats induced with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The animals (36) were randomly grouped into six with six rats in each group. Testosterone and oestradiol every other day for 28 days was used to induce hyperplasia. The test groups (2 - 4) were treated with 200, 400 and 800 mg/kg body weight of extract for another 28 days. Group 5 was given the standard drug while group 6 served as negative control. At the end of the treatment period, the rats were sacrificed under anesthesia and blood samples collected for biochemical analysis. The results showed that in the animals exposed to the inducing agents increased significantly (p <0.05) in activity of MDA, ACP and PSA levels whereas there was a significant (p >0.05) decrease in the activities of GR, CAT and SOD as compared with the normal control. -

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitory Activity of Melinjo (Gnetum Gnemon L.) Seed Extracts and Molecular Docking of Its Stilbene Constituents

Online - 2455-3891 Vol 10, Issue 3, 2017 Print - 0974-2441 Research Article ANGIOTENSIN CONVERTING ENZYME INHIBITORY ACTIVITY OF MELINJO (GNETUM GNEMON L.) SEED EXTRACTS AND MOLECULAR DOCKING OF ITS STILBENE CONSTITUENTS ABDUL MUN’IM1*, MUHAMMAD ASHAR MUNADHIL1, NURAINI PUSPITASARI1, AZMINAH2, ARRY YANUAR2 1Department of Pharmacognosy-Phytochemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Indonesia, Depok 16424, Indonesia. 2Department of Biomedical Computation, Faculty of Pharmacy, Universitas Indonesia, Depok 16424, Indonesia. Email: [email protected] Received: 10 November 2016, Revised and Accepted: 30 November 2016 ABSTRACT Objectives: To evaluate the angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitory activity of melinjo (Gnetum gnemon) seed extract and to study molecular docking of stilbene contained in melinjo seeds. Methods: Melinjo seed powders were extracted with n-hexane, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water successively. The extracts were evaluated ACE inhibitory activities using ACE kit-Wist and the phenolic content using Folin–Ciocalteu method. The extract demonstrated the highest ACE inhibitory activity was subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to know its stilbene constituent. The stilbene constituents in melinjo seed were performed molecular docking using AutoDock Vina, and ligand-receptor Interactions were processed using Ligand Scout. Results: The ethyl acetate extract demonstrated the highest ACE inhibition activity with inhibitory concentration 50% value of 9.77 × 10 −8 μg/mL inhibitor),and the highest as in silicototal phenolicmolecular content docking (575.9 studies mg demonstrated gallic acid equivalent/g). that they fit Ultra-performance into the lisinopril receptors.LC-MS analysis of ethyl acetate extract has detected the existency of resveratrol, gnetin C, ε-viniferin, and gnemonoside A/B. -

Shri R. L. T College of Science, Akola 2019-2020 Department of Botany

Shri R. L. T College of Science, Akola 2019-2020 Department of Botany B. Sc-1 Semester-II Paleobotany, Gymnosperm, Morphology and Utilization of Plants Solve the Following MCQ’s Test Max.Marks:30 Time:60Mins 1) The study of past geological plant life is done in branch called as ….. a)Botany b)Paleobotany c)History d)Anthropology 2)The father of Indian paleobotany is…. a)Homi Bhabha b) C.V. Raman c)Maheshwari d)Birbal Sahani 3) The earth is supposed to be originated before…. a) 4.6 billion years ago b)3.4 billion years ago c) 4.6 million years ago d)none of these 4)The oldest era in which life is originated was on the earth. a)proterozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)Paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 5)The following era is called as “age of ferns” a)proterozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 6) The following era is called as era of Modern Life…. a)Coenozoic era b)Archeozoic era c)Paleozoic era d)Mesozoic era 7) Sphenopteris hoeninghausii is the….. a)stem b)root c)leaves d)ovule 8) Root of L.oldhamia is called as…. a) Sphenopteris hoeninghausii b)Kaloxylon hookeri c)Lagenostoma lomaxii d)Rachiopteris aspera 9) Cycadeoidea is also known as…. a)Lyginopteris b)Bennettites c) Pinus d)Gnetum 10) The manoxylic wood refers to........... a)single ring of xylem b)hard and compressed c)loose and soft d)many rings of xylem. 11) Endosperm in gymnosperm is............. a) haploid b)diploid c)triploid d)tetraploid 12) The ovules in gymnosperms are... -

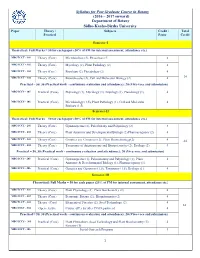

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 Onward)

Syllabus for Post Graduate Course in Botany (2016 – 2017 onward) Department of Botany Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University Paper Theory / Subjects Credit / Total Practical Paper Credit Semester-I Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 101 Theory (Core) Microbiology (2), Phycology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 102 Theory (Core) Mycology (2), Plant Pathology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 103 Theory (Core) Bryology (2), Pteridology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 104 Theory (Core) Biomolecules (2), Cell and Molecular Biology (2) 4 24 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 105 Practical (Core) Phycology (1), Mycology (1), Bryology (1), Pteridology (1). 4 MBOTCCS - 106 Practical (Core) Microbiology (1.5), Plant Pathology (1), Cell and Molecular 4 Biology (1.5). Semester-II Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 201 Theory (Core) Gymnosperms (2), Paleobotany and Palynology (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 202 Theory (Core) Plant Anatomy and Developmental Biology (2) Pharmacognosy (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 203 Theory (Core) Genetics and Genomics (2), Plant Biotechnology(2) 4 24 MBOTCCT - 204 Theory (Core) Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics (2), Ecology (2) 4 Practical = 50, 30 (Practical work - continuous evaluation and attendance); 20 (Viva-voce and submission) MBOTCCS - 205 Practical (Core) Gymnosperms (1), Palaeobotany and Palynology (1), Plant 4 Anatomy & Developmental Biology (1), Pharmacognosy (1). MBOTCCS - 206 Practical (Core) Genetics and Genomics (1.5), Taxonomy (1.5), Ecology (1). 4 Semester-III Theoretical: Full Marks = 50 for each paper (20% of FM for internal assessment, attendance etc.) MBOTCCT - 301 Theory (Core) Plant Physiology (2), Plant Biochemistry (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 302 Theory (Core) Economic Botany (2), Bioinformatics (2) 4 MBOTCCT - 303 Theory (Core) Elements of Forestry (2), Seed Technology (2). -

PG and Research Deparment of Botany Pteridophytes, Gymnosperms and Paleobotany

PG and Research Deparment of Botany Pteridophytes, Gymnosperms and Paleobotany Part-A 1. The vascular tissue is confined to the central region of the stem forming: (a) Bundles (b) stele (c) Cortex (d) Pericycle 2. The leaves which bear the sporangia are called: (a) sporophylIs (b) Bract (c) Cone (d) Strobilus 3. One or two peripheral layers persist for the nourishment of the developing spores. These nourishing cells form: (a) Elators (b) Sopores (c) Jacket (d) tapetum. 4. Match gametophyte with one of the followings: (a) Prothallus (b) Thallus (c) Cone (d) Strobilus 5. Selaginella belongs to division (a) Lycopsida (b) Pteropsida (c) Psilopsida (d) Sphenopsida 6. Hone tails are: (a) Lycopsida (b) Pteropsida (c ) Psilopsida (d) Sphenopsida 7. Marsilea belongs: (a) Lycopsida (b) Pteropsida (c) Psilopsida (d) Sphenopsida 8. Which of the followings is fern? (a) Psilopsida (b) Pteropsida (c) Lycopsida (d) Sphenopsida 9. Which of the followings is most primitive division? (a) Lycopsida (b) Pteropsida (c) Psilopsida (d) Sphenopsida 10. Club mosses are: (a) Lycopsida (b) Pteropsida (c) Psilopsida (d) Sphenopsida 11. The protostele in which xylem core is Smooth and rounded is: (a) Haplostele (b) Actinostlele (c) Plectostele (d) Siphonostele 12. The protostele in which xylem core is star like is called: (a) Haplostele (b) Actinostlele (c) Plectostele (d) Siphonostele 13. The siphonostele in–which two cylinders of vascular tissue are present in the stele is: (a) Haplostele (b) Actinostlele (c) Plectostele (d) Polycyclic 14. In Xylem in which protoxylem is lying in the middle of Metaxylem is: (a) Exarch (b) Mesarch (c) Endarch (d) Diarch 15. -

The Ephedra, the Gnetum and the Welwitschia. Genus

MODULE I UNIT 4 THE PHYLUM GNETOPHYTA This phylum consists of three genera; the Ephedra, the Gnetum and the Welwitschia. Genus: Ephedra There are about 100 known species of gnetophytes. They are unique among the gymnosperms in having vessels in the xylem. More than half of the gnetophytes are species of joint firs in the genus Ephedra. These shrubby plants inhabit drier regions of southwestern North America. Their tiny leaves are produced in twos and threes at a node and turn brown soon after they appear. The stems and branches, which are often whorled, are slightly ribbed; they are photosynthetic when they are young (Fig. 14). The leaves are little more than scales; therefore, most photosynthesis is conducted by the green stem. Before pollination, the ovules of Ephedra produce a small tubular extension resembling the neck of a miniature bottle extending into the air. Sticky fluid oozes out of this extension, which constitutes the micropyle, and airborne pollen catches in the fluid. Male and female strobili may be produced on the same plant or on different ones, depending on the species. Figure 14: Joint fir (Ephedra) 1 Economic Importance of Ephedra Joint fir is the source of the drug ephedrine, an alkaloid that constricts swollen blood vessels and also a mild stimulant. An overdose can cause death. It is also used as a tea in Chinese herbal medicine. Genus: Gnetum The members of Gnetum occur in the tropics of Africa, South America, and South Asia. Most are vine-like, with broad leaves similar to those of flowering plants (Fig.15). -

Gnetum Africanum Gnetaceae Welw

Gnetum africanum Welw. Gnetaceae LOCAL NAMES English (eru); French (koko); Igbo (okazi); Portuguese (nkoko) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Gnetum africanum is a dioecious forest perrenial liana up to 10 m long but sometimes longer; branches somewhat thickened at the nodes, glabrous. Leaves decussately opposite, sometimes in whorls of 3, simple, ovate- oblong or elliptic-oblong, more rarely lanceolate, 5-13 cm long, 2- 5 cm broad, attenuate at base, abruptly acuminate, obtuse or minutely Gnetum africanum leaves apiculate, entire, thick-papery, glabrous, pale green above, paler beneath, (commercialization) (Ebenezer Asaah) with 3-6 pairs of strongly curved lateral veins looped near the margin; stipules absent; petiole up to 1 cm long. Inflorescence an unbranched catkin, axillary or terminal on a short branch, solitary but male inflorescences at apex of branches often in groups of 3, up to 8 cm long, jointed, peduncle 1-1.5 cm long, with a pair of scale-like, triangular bracts; male inflorescence with slender internodes and whorls of flowers at nodes; female inflorescence with slightly turbinate internodes and 2-3 flowers at each node. Flowers small, c. 2 mm long, with moniliform hairs at base and an envelope; male flowers with a tubular envelope and exserted staminal column bearing 2 anthers; female flowers with cupular envelope and naked, sessile ovule. Seed resembling a drupe, ellipsoid, 10-15 mm × 4-8 mm, apiculate, enclosed in the fleshy envelope, orange-red when ripe, with copious endosperm. This lianoid species lacks fibre-tracheids characteristic of G. gnemon. However, tori are clearly present in tracheary elements of this species. In Africa, there are only two species, G.africanum and G. -

990 PART 23—ENDANGERED SPECIES CONVENTION Subpart A—Introduction

Pt. 23 50 CFR Ch. I (10–1–01 Edition) Service agent, or other game law en- 23.36 Schedule of public meetings and no- forcement officer free and unrestricted tices. access over the premises on which such 23.37 Federal agency consultation. operations have been or are being con- 23.38 Modifications of procedures and nego- ducted; and shall furnish promptly to tiating positions. such officer whatever information he 23.39 Notice of availability of official re- may require concerning such oper- port. ations. Subpart E—Scientific Authority Advice (c) The authority to take golden ea- [Reserved] gles under a depredations control order issued pursuant to this subpart D only Subpart F—Export of Certain Species authorizes the taking of golden eagles when necessary to seasonally protect 23.51 American ginseng (Panax domesticated flocks and herds, and all quinquefolius). such birds taken must be reported and 23.52 Bobcat (Lynx rufus). turned over to a local Bureau Agent. 23.53 River otter (Lontra canadensis). 23.54 Lynx (Lynx canadensis). 23.55 Gray wolf (Canis lupus). PART 23—ENDANGERED SPECIES 23.56 Brown bear (Ursus arctos). CONVENTION 23.57 American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis). Subpart A—Introduction AUTHORITY: Convention on International Sec. Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna 23.1 Purpose of regulations. and Flora, 27 U.S.T. 1087; and Endangered 23.2 Scope of regulations. Species Act of 1973, as amended, 16 U.S.C. 23.3 Definitions. 1531 et seq. 23.4 Parties to the Convention. SOURCE: 42 FR 10465, Feb. 22, 1977, unless Subpart B—Prohibitions, Permits and otherwise noted.