2 What the Popular Music Industry REALLY Is, and Where It Came from 101

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Autoethnography of Scottish Hip-Hop: Identity, Locality, Outsiderdom and Social Commentary

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repository@Napier An autoethnography of Scottish hip-hop: identity, locality, outsiderdom and social commentary Dave Hook A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy June 2018 Declaration This critical appraisal is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It has not been previously submitted, in part or whole, to any university or institution for any degree, diploma, or other qualification. Signed:_________________________________________________________ Date:______5th June 2018 ________________________________________ Dave Hook BA PGCert FHEA Edinburgh i Abstract The published works that form the basis of this PhD are a selection of hip-hop songs written over a period of six years between 2010 and 2015. The lyrics for these pieces are all written by the author and performed with hip-hop group Stanley Odd. The songs have been recorded and commercially released by a number of independent record labels (Circular Records, Handsome Tramp Records and A Modern Way Recordings) with worldwide digital distribution licensed to Fine Tunes, and physical sales through Proper Music Distribution. Considering the poetics of Scottish hip-hop, the accompanying critical reflection is an autoethnographic study, focused on rap lyricism, identity and performance. The significance of the writing lies in how the pieces collectively explore notions of identity, ‘outsiderdom’, politics and society in a Scottish context. Further to this, the pieces are noteworthy in their interpretation of US hip-hop frameworks and structures, adapted and reworked through Scottish culture, dialect and perspective. -

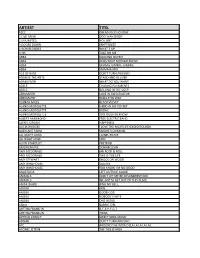

WEB KARAOKE EN-NL.Xlsx

ARTIEST TITEL 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY 2 LIVE CREW DOO WAH DIDDY 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 4 NON BLONDES WHAT´S UP A HA TAKE ON ME ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMMIE GIMMIE GIMMIE ABBA MAMMA MIA ACE OF BASE DON´T TURN AROUND ADAM & THE ANTS STAND AND DELIVER ADAM FAITH WHAT DO YOU WANT ADELE CHASING PAVEMENTS ADELE ROLLING IN THE DEEP AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR AEROSMITH WALK THIS WAY ALANAH MILES BLACK VELVET ALANIS MORISSETTE HAND IN MY POCKET ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW ALBERT HAMMOND FREE ELECTRIC BAND ALEXIS JORDAN HAPPINESS ALICIA BRIDGES I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE (DISCO ROUND) ALIEN ANT FARM SMOOTH CRIMINAL ALL NIGHT LONG LIONEL RICHIE ALL RIGHT NOW FREE ALVIN STARDUST PRETEND AMERICAN PIE DON MCLEAN AMY MCDONALD MR ROCK & ROLL AMY MCDONALD THIS IS THE LIFE AMY STEWART KNOCK ON WOOD AMY WINEHOUSE VALERIE AMY WINEHOUSE YOU KNOW I´M NO GOOD ANASTACIA LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE ANIMALS DON´T LET ME BE MISUNDERSTOOD ANIMALS WE GOTTA GET OUT OF THIS PLACE ANITA WARD RING MY BELL ANOUK GIRL ANOUK GOOD GOD ANOUK NOBODY´S WIFE ANOUK ONE WORD AQUA BARBIE GIRL ARETHA FRANKLIN R-E-S-P-E-C-T ARETHA FRANKLIN THINK ARTHUR CONLEY SWEET SOUL MUSIC ASWAD DON´T TURN AROUND ATC AROUND THE WORLD (LA LA LA LA LA) ATOMIC KITTEN THE TIDE IS HIGH ARTIEST TITEL ATOMIC KITTEN WHOLE AGAIN AVRIL LAVIGNE COMPLICATED AVRIL LAVIGNE SK8TER BOY B B KING & ERIC CLAPTON RIDING WITH THE KING B-52´S LOVE SHACK BACCARA YES SIR I CAN BOOGIE BACHMAN TURNER OVERDRIVE YOU AIN´T SEEN NOTHING YET BACKSTREET BOYS -

Collected Press Clips

Future of Music Coalition press clips following release of radio study November 2002 - January 2003 Study Shows an Increase in Overlap of Radio Playlists; The report by an artists' rights group says that morestations with different formats play the same songs. Industry officials disagree. By Jeff Leeds Los Angeles Times, November 15, 2002 http://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-radio15nov15,0,4652989.story Ever since the Clinton administration Moreover, the study says, radio handful of giant media companies, loosened restrictions on how many companies that have grown the most including Clear Channel and Viacom radio stations a broadcaster could under deregulation are limiting the Inc.'s Infinity Broadcasting, which own, record label executives have choice of music by operating two or operates more than 180 stations. complained that media consolidation more stations in the same market Radio industry officials dismissed the would lead to bland playlists and with the same music format. The study's conclusions. homogenous programming. report said that Clear Channel Communications Inc., the nation's "The big gap in the logic is that the Now a coalition of musicians and biggest radio conglomerate, has 143 authors don't believe radio stations independent record label executives stations with similar music formats in care about what consumers do," said say they have statistical proof that the same market. Jodie Renk, general manager of Core the relaxation of ownership rules has Callout Research, a firm that tests stifled recording artists and The study contradicts the conclusions new songs with radio listeners. "damaged radio as a public of a September report by the Federal resource." The study was done by the Communications Commission. -

Download YAM011

yetanothermagazine filmtvmusic aug2010 lima film festival 2010 highlights blockbuster season from around the world in this yam we review // aftershocks, inception, toy story 3, the ghost writer, taeyang, se7en, boa, shinee, bibi zhou, jing chang, the derek trucks band, time of eve and more // yam exclusive interview with songwriter diane warren film We keep working on that, but there’s toy story 3 pg4 the ghost writer pg5 so much territory to cover, and so You know the address: aftershocks pg6 very little of us. This is why we need [email protected] inception pg7 lima film festival// yam contributors. We know our highlights pg9 readers are primarily located in the amywong // cover// US, but I’m hoping to get people yam exclusive from other countries to review their p.s.: I actually spoke to Diane interview with diane warren pg12 local releases. The more the merrier, Warren. She's like the soundtrack music people. of our lives, to anyone of my the derek trucks band - roadsongs pg16 generation anyway. Check it out. se7en - digital bounce pg16 shinee - lucifer pg17 Yup, we’re grovelling for taeyang - solar pg17 contributors. I’m particularly eminem - recovery pg18 macy gray - the sellout pg18 interested in someone who is jing chang - the opposite me pg18 located in New York, since we’ve bibi zhou - i.fish.light.mirror pg18 nick chou - first album pg19 received a couple of screening boa - hurricane venus pg19 invites, but we got no one there. tv Interested? Hit me up. bad guy pg20 time of eve pg20 books uso. -

A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura

The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia by Laura L. Bunting-Hudson Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Laura L. Bunting-Hudson All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Art of the Hustle: A Study of the Rap Music Industry in Bogota, Colombia Laura L. Bunting-Hudson How do rap artists in Bogota, Colombia come together to make music? What is the process they take to commodify their culture? Why are some rappers able to become socially mobile in this process, while others are less so? What is technology’s role in all of this? This ethnography explores those questions, as it carefully documents the strategies utilized by various rap groups in Bogota, Colombia to create social mobility, commoditize products and to create a different vision of modernity within the hip-hop community, as an alternative to the ideals set forth by mainstream Colombian society. Resistance Art Poetry (RAP), is said to have originated in the United States but has become a form of international music. In conducting ethnographic research from December of 2012 to October 2014, I was able to discover how rappers organize themselves politically, how they commoditize their products and distribute them to create various types of social mobilities. In this dissertation, I constructed models to typologize rap groups in Bogota, Colombia, which I call polities of rappers to discuss how these groups come together, take shape, make plans and execute them to reach their business goals. -

Sam Moore BIO for Years Sam Moore Was Best Known for His Work With

Sam Moore BIO For years Sam Moore was best known for his work with the historic soul duo Sam & Dave. The rapid-fire style, built on the call and response of gospel, was fashioned and pioneered by Sam and became the trademark of the duo. Songs like Hold On I’m Coming, I Thank You, When Something Is Wrong With My Baby, Soul Sister, Brown Sugar, Wrap It Up and his monster hit Soul Man catapulted them up both the Pop and R & B Charts. Sam & Dave sold more than 10 million records worldwide. The music and sound of Sam & Dave became so popular that the duo served as the inspiration for The Blues Brothers parody by Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. Though he has tremendous love and respect for the music he created as “the voice” of the duo, Sam, who has been called “the blast furnace of soul,” has maintained his appeal and his stardom as a solo artist and continues to tour scoring critical acclaim for his work. He recorded Rainy Night In Georgia, as a duet with Conway Twitty, which earned them a platinum record as well as two Country Music Association Awards nominations. This was Twitty’s last recording. The Grammy Award winner has countless television appearances globally including The Leno Show, Late Night With David Letterman, Later With Jools, The Today Show, Entertainment Tonight, The Grammys and many others. Sam has also appeared in several major movies including One Trick Pony, Tapeheads, Blues Brothers 2000 and Night of The Golden Eagle. A documentary filmed by the legendary D.A. -

Quintet/String Orchestra Repertoire

Millington Strings Quintet Repertoire 2019 Title Composer A Chloris Reynaldo Hahn A Summer Place Percy Faith/Max Steiner A Thousand Years Hodges/Perri Adagietto fr Symphony # 5 Gustav Mahler Adagio Tomaso Albinoni Adagio Cantabile Ludwig van Beethoven Agnus Dei Johann Sebastian Bach Air (fr 2nd French Suite) Johann Sebastian Bach Air (fr Water Music) Georg Friedrich Handel Air (On The G String) Johann Sebastian Bach All Hail to Thee Ingemar Braennstroem All I Ask Of You Andrew Lloyd-Webber All I Want Is You Bono All You Need Is Love John Lennon/Paul McCartney Amazing Grace English/American Traditional Americana Suite, Mvt 1: 400 HP, Heavy Foot Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 2: Foxy Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 3: Starry Night, Starry Eyes Stephen H Millington Americana Suite, Mvt 4: Aretha Stephen H Millington And I Love Her John Lennon/Paul McCartney And So It Goes Billy Joel Andante (fr Water Music) Georg Friedrich Handel Andante Festivo Jean Sibelius Ang Tangi Kong Pag-Ibig Constancio de Guzman Anitra's Dance Edvard Grieg Aniversary Waltz Dave Franklin/Al Dubin April In Portugal Raul Ferrao Aria sopra la Bergamasca Marco Uccellini Tuesday, August 6, 2019 Page 1 of 14 Title Composer Arioso Johann Sebastian Bach Asher Bara Israeli Traditional Asher Boro Israeli Traditional Ashokan Farewell Jay Ungar At Last Mack Gordon/Harry Warren Ave Maria Johann Sebastian Bach/Charles Gounod Ave Maria Franz Schubert Bachianas # 5 Heitor Villa-Lobos Badinerie Johann Sebastian Bach Ballade Ciprian Porumbescu Be Thou My Vision -

The Industry Surrounding Songwriting Continues to Evolve, but the Art of Moulding a Great Record Remains the Same

Billie the kid: Billie Eilish The industry surrounding songwriting continues to evolve, but the art of moulding a great record remains the same. Here, Music Week asks a selection of the biz’s stars to name the greatest living hitmaker… ------------ B Y BEN HOMEWOOD, GEORGE GARNER, MARK SUTHERLAND, JAMES HANLEY & ANDRE PAINE ------------ Billie Eilish “The only person I’ve been completely blown away with recently is Billie Eilish. She’s phenomenal and I Diane Warren really like the idea of that [songwriting] relationship “Diane Warren – her writing credits say it all. Aerosmith, Celine Dion, Cher, Rihanna, Bon between her and her brother [Finneas O’Connell]. It’s Jovi, Michael Bolton, Meat Loaf, Kiss, Pet Shop Boys, Mariah Carey, Alice Cooper, Eric got elements of Feist, but wrapped up in a completely Clapton, Roy Orbison, LeAnn Rimes, Lionel Richie, Tom Jones, Tina Turner are just a subversive way, which is blowing me away.” selection of artists she has written for. It’s probably easier to put a list together of people she Crispin Hunt, songwriter and chair, hasn’t written with. She’s been writing hits for decades and she’s still writing hits.” Ivors Academy Andy Copping, executive president of UK touring, Live Nation John Mayer “I think he’s incredibly underestimated. His songs touch Bruno Mars something, lyrically, he addresses subjects that are “It’s a tough one to decide on the best living 24K gold: incredibly personal and well executed, and incredibly songwriter. I would probably go with Bruce Bruno Mars melodic. He is underrated and I’m surprised he doesn’t get Springsteen but I thought about it and, while more airplay. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr.