Jinn N' (No Freshly Squeezed) Juice: Interracial Tensions and Muslim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news November 2005 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 5, No. 2 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 The Ballad of Mission Statement Contributors Indie Girls Music Fests om rosseau Full Circle.. …………4 Counter Culture Coincidence Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch... ………6 Tristan Prettyman Traditional Jazz Riffs Live Jazz Aaron Bowen Parlor Showcase …8 Tom Brosseau Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Of Note. ……………12 Crash Carter D’vora Amelia Browning Peter Sprague Precious Bryant Aaron Bowen Blindspot The Storrow Band See Spot Run Tom Brosseau ‘Round About ....... …14 November Music Calendar The Local Seen ……15 Photo Page NOVEMBER 2005 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat In Greek mythology Demeter was the most generous of the great Olympian goddesses, beloved for her service to mankind with the gift of the harvest, the reward for cultivating the soil. Also known as Ceres in Roman mythology, Demeter was credited with teaching humans how to grow, preserve, and prepare grain. Demeter was thought to be responsible for the fertility of the land. She was the only Greek SAN DIEGO goddess involved in the lives of the common folk on a day-to-day basis. While others occasionally “dabbled” in human affairs when it ROUBADOUR suited their personal interests, or came to the aid of “special” mortals they favored, Demeter was truly the nurturer of mankind. She was Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, also the only Greek goddess who could truly empathize with human suffering and grief, having fully experienced it herself. -

Organic Hip Hop Conference

AADS Graduate Student Association presents Organic Hip Hop Conference Building a National Movement of Responsibility Friday October 29th, 2010 Florida International University GC 243 Modesto Maidique Campus Co-sponsored by African and African Diaspora Studies Program and Difference Makers, Inc. and the Council for Student Organizations Teacher Workshop 9:00 am – 3:00 pm Presenters: Antonio Ugalde (Tony Muhammad) – Using Hip Hop to teach the history of Blacks during the Civil War Jasiri Smith (Jasiri X) – Free the Jena 6 Lesson Arian Nicole (Arian Muhammad AKA Poetess) – Using poetry as a teaching tool Adisa Banjoko – The developing chess programs in schools Building a National Movement of Responsibility Panel Discussion 7:30 pm – 9 pm Panel Discussion: Jasiri Smith (Jasiri X) Arian Nicole (Arian Muhammad) Adisa Banjoko (along with at least one panelist representing the Miami community) Performance and poetry Open mic 9:30pm 11:00pm This event is open to all FIU and non-FIU student and to the entire community. Bios of Presenters Arian Muhammad Arian Muhammad is a performance artist, poet, cultural analyst, and founder of The MIA Music Is Alive campaign for a Hip Hop Day of Service. As a hip hop artist Arian has opened up for def jam poet Jessica Care Moore, and recorded with hip hop icon KRS ONE. Arian serves as a student minister of arts and culture in the Nation of Islam and is most noted for her work in the Flint community as the executive director of C.H.A.N.G.E., a hip hop and self image organization for young women. -

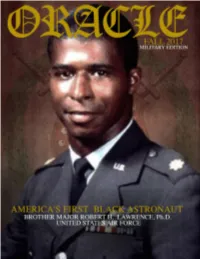

The Oracle - Fall 2017 1 TABLE of CONTENTS the Oracle OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY, INC

The Oracle - Fall 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Oracle OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY, INC. International Headquarters 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 404-284-5533 U.S. Army's Lt. General Brother William E. "Kip" Ward was the Commander, U.S. Africa Command. Bro. Ward is one of Omega's highest ranking officers in Volume 89 No. 33 the Fraternity's history. FALL 2017 The official publication of Grand Basileus Message 7 Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Bro. Antonio F. Knox, Sr. America's First Black Astronaut 10 Send address changes to: Bro. Major Robert H. Lawrence Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Military Hall of Honor Attn: Grand KRS Omega Psi Phi's Military Men 12 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 Omega's War Chapter 14 The next Oracle deadline: By Bro. Jonathan A. Matthews January 15, 2018 *Deadlines are subject to change. Military Profiles 16 Brothers Jackson and Jones Please Email all editorial concerns, comments, and information to Military and Sports 20 Bro. M. Brown, Editor of The Oracle Brothers Black and Simmons [email protected] Leadership Conference 2017 24 Cincinnati, Ohio ORACLE COVER DESIGN By DEPARTMENTS Bro. Haythem Lafhaj Congressional Black Caucus-30 Legal News-32 Kappa Psi Graduate Chapter Omega's Office of Compliance-34 Lifetime Achievement Award-36 Undergraduate News-38 IHQ Website Editor District News-39 Brother Quinest Bishop Omega Chapter-56 2 The Oracle - Fall 2017 THE ORACLE Editorial Board EDITOR’S NOTES International Editor of The Oracle Brother Milbert O. Brown, Jr. n this issue we pay Itribute to the Brothers of Assistant Editor of The Oracle-Brother Norman Senior Omega who have served and are still serving in the Director of Photography- Brother James Witherspoon United States Armed Emeritus Photographer-Brother John H. -

Summer 2011 Bulletinprimary.Indd

A PUBLICATION OF THE SILHA CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF MEDIA ETHICS AND LAW | SUMMER 2011 Not Just a ‘Rogue Reporter’: ‘Phone Hacking’ Scandal Spreads Far and Wide The so-called “phone hacking” scandal has led to more than Murdoch Closes News of the World and a dozen arrests, resignations by top News Corp. executives Speaks to Parliament while Public and British police, the launching of several new investigations Outrage Grows over Tabloid Crime, into News Corp. business practices, and pressured Murdoch to retreat from a business deal to purchase the remaining Collusion, and Corruption portion of BSkyB that he did not own. The U.S. Department of Justice and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) massive ethical and legal scandal enveloped the are reportedly conducting preliminary investigations into the Rupert Murdoch-owned British tabloid News of possibility of international law violations. The FBI is reportedly the World in the summer of 2011, leading to its investigating allegations that Murdoch journalists hacked into sudden closure. New allegations arose almost the phones of victims of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks daily that reporters and private investigators or their families. British police have teamed up with Scottish Aillegally accessed the voice mail messages of politicians, authorities to continue investigating claims of phone hacking. celebrities, and private citizens. The revelations sparked Parliament launched a formal inquiry into the scandal and has worldwide public outcry and led to sweeping law enforcement questioned top News Corp. offi cials including Rupert Murdoch investigations directed at top editors of the paper, executives and his son, James Murdoch. -

Bay Guardian | August 26 - September 1, 2009 ■

I Newsom screwed the city to promote his campaign for governor^ How hackers outwitted SF’s smart parking meters Pi2 fHB _ _ \i, . EDITORIALS 5 NEWS + CULTURE 8 PICKS 14 MUSIC 22 STAGE 40 FOOD + DRINK 45 LETTERS 5 GREEN CITY 13 FALL ARTS PREVIEW 16 VISUAL ART 38 LIT 44 FILM 48 1 I ‘ VOflj On wireless INTRODUCING THE BLACKBERRY TOUR BLACKBERRY RUNS BETTER ON AMERICA'S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. More reliable 3G coverage at home and on the go More dependable downloads on hundreds of apps More access to email and full HTML Web around the globe New from Verizon Wireless BlackBerryTour • Brilliant hi-res screen $ " • Ultra fast processor 199 $299.99 2-yr. price - $100 mail-in rebate • Global voice and data capabilities debit card. Requires new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. • Best camera on a full keyboard BlackBerry—3.2 megapixels DOUBLE YOUR BLACKBERRY: BlackBerry Storm™ Now just BUY ANY, GET ONE FREE! $99.99 Free phone 2-yr. price must be of equal or lesser value. All 2-yr. prices: Storm: $199.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Curve: $149.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Pearl Flip: $179.99 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. Add'l phone $100 - $100 mail-in rebate debit card. All smartphones require new 2-yr. activation on a voice plan with email feature, or email plan. While supplies last. SWITCH TO AMERICA S LARGEST, MOST RELIABLE 3G NETWORK. Call 1.800.2JOIN.IN Click verizonwireless.com Visit any Communications Store to shop or find a store near you Activation fee/line: $35 ($25 for secondary Family SharePlan’ lines w/ 2-yr. -

Public Affairs Tuesday, February 23, 2010 Writer/Contact: John F

Public Affairs News Service Tuesday, February 23, 2010 Writer/Contact: John F. Greenman, 706/542-1081, [email protected] UGA awards McGill Medal for Journalistic Courage to Chauncey Bailey Project reporters Athens, Ga. – Four reporters associated with the Chauncey Bailey Project will be honored by the University of Georgia for journalistic courage. Thomas Peele, Josh Richman, Mary Fricker and Bob Butler will receive the McGill Medal for Journalistic Courage on Wednesday, March 24, at the UGA Grady College of Journalism and Mass Communication. “Peele, Richman, Fricker and Butler’s reporting was truly courageous,” wrote Oakland Tribune editor Martin G. Reynolds in his nomination. “A reporter was killed and they continued and expanded his work despite obvious dangers.” The reporter was Chauncey Bailey, editor of the Oakland Post, who was murdered in 2007 while investigating black Muslims and their Your Black Muslim Bakery, headquartered in Oakland, Calif. The man charged with Bailey’s killing told a court he was ordered by the group’s leader to murder Bailey “to stop this story.” The four reporters wrote more than 100 stories about the group, the murder, and the police investigation. Reynolds wrote, “Their reportage forced the indictment of the group’s leader on murder changes for ordering the assassination.” Peele and Richman are reporters for The Oakland Tribune/Bay Area News Group. Peele is an investigative reporter whose work focuses on government malfeasance and corruption. A 25-year veteran of newspapers on both coasts, Peele has won four national reporting awards. Richman covers state and federal politics. He reported for the Express- Times in Easton, Pa. -

The Oakland Tribune (Oakland

The Oakland Tribune (Oakland, CA) August 17, 2004 Tuesday Muslim bakery leader confirmed dead BYLINE: By Harry Harris and Chauncey Bailey - STAFF WRITERS SECTION: MORE LOCAL NEWS LENGTH: 917 words OAKLAND -- A man found buried in a shallow grave last month in the Oakland hills was identified Monday as Waajid Aljawaad Bey, 51, president and chief executive officer of Your Black Muslim Bakery, police said. Police would not say how Bey, who assumed leadership of the bakery after the death of Yusuf Bey in September, had died. But Sgt. Bruce Brock said police are investigating the case "as a definite homicide." He would not say whether police think Bey was killed elsewhere before being buried at the site or was killed there and then buried. And while police are certain Bey was deliberately killed, Brock said despite a great deal of speculation, "we're not sure of a motive at this time." Some bakery insiders have feared that Bey's fate may be related to rivalries and a power play in the wake of Yusuf Bey's death from cancer in 2003. Although Bey never really discussed his Muslim activities with relatives, family members "are quite sure [the death] had something to do with him taking over" the organ ization, said a relative who asked not to be named. Bey's badly decomposed remains were discovered July 20 by a dog being walked by its owner on a fire trail that runs off the 8200 block of Fontaine Street near King Estates Middle School. Because of the circumstances surrounding the discovery of the body, it was classified as a homicide at the time, the city's 46th. -

The Texas Observer MAY 13, 1966

The Texas Observer MAY 13, 1966 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c BLACK HOUSTON Houston Ward, and to the east, one can drive remains segregated from decent wages, through miles of elegantly manicured in- Black Houston reaches from the stink decent housing, and white schools, except of the ship channel at Harrisburg, where a dustrial park without realizing that, two in the most token way. The story of the Negro deckhand can walk a block from his blocks away, families of nine are crowded maintenance of de facto segregation in ship for a piece of heroin or a night with into one-room "apartments" which rent Houston explains the plight well, for the a whore, south and west to the shaded for $8 a week. Here, the invisibility of the Negro now has exhausted the sanctioned poor, which Michael Harrington wrote of avenues of "Sugar Hill," where a Negro methods of local pressure and is moving in - The Other America, dentist can stand on the walk of his $50,000 is carried to its ulti- on to court, in a suit which was scheduled home and watch a white boy weed the park mate. The white Houstonian would be as to be filed this week, to stop a building surprised by the slightly flaking elegance across the street. The deckhand pays for program that the suit alleges to be a tool of "Sugar Hill," cockpit of the thin top- his happiness by giving his hiring agent of continued de facto segregation, and to cream of Negro society, as by the degrada- one day's pay for each week worked, and seek an order desegregating all 'Houston tion of a Harrisburg home the Observer the dentist may have paid for what he has schools next September, rather than in by turning white in the eyes of other visited one day recently. -

Strategic Area Command

STRATEGIC AREA COMMAND ANNUAL REPORT 2007 2007 Strategic Area Command Annual Report - 1 - 2007 Strategic Area Command Annual Report - 2 - CAPTAIN E. TRACEY The mission of the Strategic Area Command for 2007 was to use the resources to strategically address community priorities and emerging crime trends. Emphasis was placed on “wrapping” resources around the Problem Solving Officer and the level of responsibility and accountability of the Police Service Area (PSA) Lieutenant. The primary goal of the Division is give its members the authority, training, and tools to perform problem-oriented policing and to hold them responsible for a high level of performance. The following units fell under the umbrella of SAC this year: • Police Service Area Lieutenants • Crime Reduction Teams (CRT) • Problem Solving Officers (PSO) • Traffic Section • Special Events Unit • Tactical Operations Section • Alcohol Beverage Action Team (ABAT) • Foot Patrol Unit • Crime Scene Technicians • Canine Program • Police Reserves • Gang Unit • Parole and Corrections Team (PACT) • Air Support Collectively, these units did an outstanding job in the areas of community policing, traffic enforcement and crime suppression. Through the excellent work of the men and women of SAC along with others in the department, some areas in the city saw dramatic decreases in Part 1 crime (See report for PSA 3 and 5). STAFFING SAC has benefited from the assignment of officers under Measure Y. While the Department has struggled to increase overall staff, it has maintained its commitment to Measure Y by assigning 40% of the officers who complete field training to assignments as PSOs in SAC. These new assignments have had collateral effects on other parts of the Department and Division. -

A Call for Justice Et," Said March Cohen, One of the Defense Manipulation Began to Hit the Case

~--- ~ ?-4'. =-:;::--~,.~ ~~ ~ "'-~,';;-'--::=-...::........;....-~ - _..!cc,,. :;::-,,,,, -=- -~·c:;,-~ ........ ,,,___ ··=== =. _: ·-~~~=--~..::::.~-..,,.,....,., ~~:__.~-' l Published Monthly by The Commemoration Committee for The Black Panther Party VOLUME 3 NO. 5 ·· March 1993 Con1n1unit Tensions High Photo ~I ~.:~e:L!t'!f~~ A Close Look.At Famine The phenomenon of famine in the world today American soldiers currently invest ing portions of Somalia under the ban ner of famine relief are entering a coun try listed as one of three prime markets on the international cocoa exchange, with an abundance of untapped uranium deposits as well as petroleum and many other outside interests. Like many African nations suffering famine - defined by Webster's Second Un With four officers-on reasonable bail- being tried for violating Rodney King's civil rights, and a second .trial abridged Edition as "an acute and - of three black youths unable to raise hundreds of thousands of dollars - about to start,judicial rulings ap- general shortage of food in a popula . perar designed to preclude the possiblitly that institutional racism in Los Angeles might be proved in court. tion" - Somalia's agriculture has for many decades prioritized export com Los Angeles (USA) modities first. Famine exists in areas in this state and in this country, right now, here in the United States as well as around the world. "Somalia is a drop ,in the buck A Call for Justice et," said March Cohen, one of the Defense manipulation began to hit the case. They dwelt on how the LAPD Did a black jury woman contaminate authors of "Hunger 1993." Out of a home early in the face of passive plain police were placed at the edge of the her would-be jury mates by repeating world population, according to the tiff passages au contraire. -

Bush Disinformation • •

WfJRNERS 'ANfiIJARIJ 50¢ No. 856 , €<§::>C-701 14 October 2005 Judith Miller and Bush Disinformation • • I~~' --I!aJ. - AFP Ig les DPA an mperia isl ar Iraq today threatens to completely unr,l\el under the hlood) L.S. llL'Cupa Down With tion. More than -l-.()OO ci\ilians hale been killed in Baghdad alone since April. The U.S. Occupation number of American dead in Iraq is clo\ ing in on 2,O()(). \Vith the approal'h of tht' of Iraq! October 15 "'referendum" on the Iraqi constitution, the daily toll of car bomh OCTOBER 7-,\;,1'\\ }(II-A: Ji"IlIC,1 repl)rter ings and other deadly attacks i, inneas Judith ;'.,Jilkr \\~dked out of pri~on laq ing, as i~ the terror campaign carried out \Ieek after being held for nearly three hy C.S. forces in predominantl) Sunni months for refusing to testify before a areas. Illustrating the farcical nature nf grand jury ime,tigating the outing orCIA the "referendum:' earlier this \\ eek thc clgent Valerie Plame. The entire time, her prm isional Iraqi parliament rell rotl' ho,ses at the Tillles portra~ed -'filler as a the rules to make it all but impos<;ihle for martyr in the CIlI,C of the "frl'e pre,ss." the Sunni population, whose inten:sl'> the But in Lcd, ~hller was freed because she document makes deCided I) secondary til had promised that she would immediately those of the Shi' ites and Kurd,. to \ ok it te,tify before the grand jury. down. Thl' mO\e was quickly scuttled as \fany liberals and leftists took up U.S. -

KPCC-KPCV-KUOR Quarterly Report JAN-MAR 2012

Quarterly Programming Report Jan- Mar 2012 KPCC / KPCV / KUOR Date Key Synopsis Guest/Reporter Duration Pasadena Police Department will deploy more officers as Occupy activists plan to demonstrate at the 1/1/2012 POLI Rose Parade. CC :19 Skiers and snowboarders across the western United States face a "snow drought" this winter on some 1/1/2012 SPOR of their favorite slopes. Unknown :16 The three-year old Clean Trucks Program at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach moves into its 1/1/2012 TRAN final phase as the year begins. Peterson :58 1/1/2012 LAW Another dozen arson fires broke out overnight in Los Angeles and West Hollywood. CC :17 1/1/2012 ART Native American creation story and bird songs come alive in new Riverside art exhibition. Cuevas 1:33 1/1/2012 MEDI We asked KPCC listeners to look back on 2011 and ahead to 2012. CC :13 1/1/2012 DC Congressmangpyy shares a New Year's Day breakfast recipe. Felde 1:33 contract with United Teachers Los Angeles – an unprecedented agreement that Deasy called “groundbreaking work,” aimed at providing more freedom for teachers, school administrators and 1/2/12 YOUT parents top,gpggpp, manage their respective schools. John Deasy 00:31 of course. Comedy Congress has hung up its Christmas stocking and finds it full of Mitt and Newt and Barack – and it’s our holiday gift to you. Perry ups the voting age; Obama very politely asks Iran for his Alonzo Bodden, Greg 1/2/12 POLI drone back and we play the highlight reel of Cain’s self-described brain twirlings! And just as we thoughtProops, Ben Gleib 00:65 Dr.