Herein, Includ- Zeeda H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb 2020 February Is Cabin Fever Month

Like Share Tweet Share this Page: Anthroposophic Medicine for Whole Person Healing & Wellness February, 2020 February is cabin fever month where winter has a strong hold. In Sacramento, it’s spring-like. We will be closed Friday, February 14. Smile, and generously use loving words, and maybe fewer hugs this germy Valentine’s! (See #3 under Coronavirus and watch 'sanitation.') Remember to have your ANNUAL check-in! Stay established with RMT so we are up- to-date if you need help in the time ahead. Our doctor-patient relationship with you is the foundation of your medical exemption – gaps in contact over a year make it look like we do not have an active doctor-patient relationship. Get in front of the calendar and get it done! Combine that with a needed sports physical or vaccine consult to plan the schedule for the safest vaccination possible. Read below about: CORONALikeVIRUS, Share Tweet Share this Page: What to do if you receive a letter from the DEPARTMENT OF INVESTIGATION , Updates on positive movement in LEGISLATION, and REACTIONS TO CALM POWDER. Also, a great free FERMENTATION SUMMIT is underway now-- join! ❤ A Voice for Choice LiveAware Expo is this month!❤ Check out the speakers, including Elana Freeland, author of Under an Ionized Sky: from chemtrails to space fence lockdown. Peaceful days MKS for all of us CORONAVIRUS 1. Prevention: Vit C, Vit A (Carlson cod liver oil), Zinc, Astragalus (if you have autoimmune disease) or Elderberry (for those without autoimmune disease); glycyrrhiza (licorice) helps treat symptoms. (We have high quality versions of these immune strengthening products for you to purchase.) Watch more on this HERE. -

August Troubadour

FREE SAN DIEGO ROUBADOUR Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, Tblues, gospel, jazz, and bluegrass music news November 2005 www.sandiegotroubadour.com Vol. 5, No. 2 what’s inside Welcome Mat ………3 The Ballad of Mission Statement Contributors Indie Girls Music Fests om rosseau Full Circle.. …………4 Counter Culture Coincidence Recordially, Lou Curtiss Front Porch... ………6 Tristan Prettyman Traditional Jazz Riffs Live Jazz Aaron Bowen Parlor Showcase …8 Tom Brosseau Ramblin’... …………10 Bluegrass Corner Zen of Recording Hosing Down Radio Daze Of Note. ……………12 Crash Carter D’vora Amelia Browning Peter Sprague Precious Bryant Aaron Bowen Blindspot The Storrow Band See Spot Run Tom Brosseau ‘Round About ....... …14 November Music Calendar The Local Seen ……15 Photo Page NOVEMBER 2005 SAN DIEGO TROUBADOUR welcome mat In Greek mythology Demeter was the most generous of the great Olympian goddesses, beloved for her service to mankind with the gift of the harvest, the reward for cultivating the soil. Also known as Ceres in Roman mythology, Demeter was credited with teaching humans how to grow, preserve, and prepare grain. Demeter was thought to be responsible for the fertility of the land. She was the only Greek SAN DIEGO goddess involved in the lives of the common folk on a day-to-day basis. While others occasionally “dabbled” in human affairs when it ROUBADOUR suited their personal interests, or came to the aid of “special” mortals they favored, Demeter was truly the nurturer of mankind. She was Alternative country, Americana, roots, folk, also the only Greek goddess who could truly empathize with human suffering and grief, having fully experienced it herself. -

Discrimination and Harassment

Dear Member of the Legislature - My name is April Groom and I am in District 54. I am a mom of a child with multiple food allergies and sensitivities and I’m concerned that if this bill passes, it will be extremely hard to get a medical exemption. I’m also concerned because my son is on an IEP. Per the law of his IEP, I believe this would be discrimination and harassment. Please oppose HB 3063. Pease read the attached letter from my 9-year-old, from District 54, who's goal it is in school this year to Be a Better writer! He has an IEP. This letter was a 2-day labor of love. We are concerned he would Be denied a puBlic education if this Bill passes and per his IEP, we feel he would Be discriminated against. His letter is attached in this email and it is also copied here fully (he got tired of writing and shortened it), included in my first point of concern, Below titled: Civil Rights/Discrimination. HB 3063 is an infringement on our right to bodily autonomy and informed consent. The US Supreme Court has ruled vaccines as 'unavoidably unsafe' and where there is risk, there must Be choice. Each and every vaccine insert for each and every vaccine lists "Death" as a possible outcome. See my 8 points of concern, listed numerically, with supporting factors, below: As a mom and a citizen of the state of Oregon, and we as parents, I am concerned aBout the following 8 points, regarding HB3063: 1).Civil Rights/ Discrimination 2). -

Organic Hip Hop Conference

AADS Graduate Student Association presents Organic Hip Hop Conference Building a National Movement of Responsibility Friday October 29th, 2010 Florida International University GC 243 Modesto Maidique Campus Co-sponsored by African and African Diaspora Studies Program and Difference Makers, Inc. and the Council for Student Organizations Teacher Workshop 9:00 am – 3:00 pm Presenters: Antonio Ugalde (Tony Muhammad) – Using Hip Hop to teach the history of Blacks during the Civil War Jasiri Smith (Jasiri X) – Free the Jena 6 Lesson Arian Nicole (Arian Muhammad AKA Poetess) – Using poetry as a teaching tool Adisa Banjoko – The developing chess programs in schools Building a National Movement of Responsibility Panel Discussion 7:30 pm – 9 pm Panel Discussion: Jasiri Smith (Jasiri X) Arian Nicole (Arian Muhammad) Adisa Banjoko (along with at least one panelist representing the Miami community) Performance and poetry Open mic 9:30pm 11:00pm This event is open to all FIU and non-FIU student and to the entire community. Bios of Presenters Arian Muhammad Arian Muhammad is a performance artist, poet, cultural analyst, and founder of The MIA Music Is Alive campaign for a Hip Hop Day of Service. As a hip hop artist Arian has opened up for def jam poet Jessica Care Moore, and recorded with hip hop icon KRS ONE. Arian serves as a student minister of arts and culture in the Nation of Islam and is most noted for her work in the Flint community as the executive director of C.H.A.N.G.E., a hip hop and self image organization for young women. -

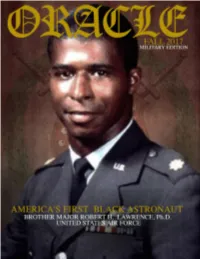

The Oracle - Fall 2017 1 TABLE of CONTENTS the Oracle OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY, INC

The Oracle - Fall 2017 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS The Oracle OMEGA PSI PHI FRATERNITY, INC. International Headquarters 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 404-284-5533 U.S. Army's Lt. General Brother William E. "Kip" Ward was the Commander, U.S. Africa Command. Bro. Ward is one of Omega's highest ranking officers in Volume 89 No. 33 the Fraternity's history. FALL 2017 The official publication of Grand Basileus Message 7 Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Bro. Antonio F. Knox, Sr. America's First Black Astronaut 10 Send address changes to: Bro. Major Robert H. Lawrence Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. Military Hall of Honor Attn: Grand KRS Omega Psi Phi's Military Men 12 3951 Snapfinger Parkway Decatur, GA 30035 Omega's War Chapter 14 The next Oracle deadline: By Bro. Jonathan A. Matthews January 15, 2018 *Deadlines are subject to change. Military Profiles 16 Brothers Jackson and Jones Please Email all editorial concerns, comments, and information to Military and Sports 20 Bro. M. Brown, Editor of The Oracle Brothers Black and Simmons [email protected] Leadership Conference 2017 24 Cincinnati, Ohio ORACLE COVER DESIGN By DEPARTMENTS Bro. Haythem Lafhaj Congressional Black Caucus-30 Legal News-32 Kappa Psi Graduate Chapter Omega's Office of Compliance-34 Lifetime Achievement Award-36 Undergraduate News-38 IHQ Website Editor District News-39 Brother Quinest Bishop Omega Chapter-56 2 The Oracle - Fall 2017 THE ORACLE Editorial Board EDITOR’S NOTES International Editor of The Oracle Brother Milbert O. Brown, Jr. n this issue we pay Itribute to the Brothers of Assistant Editor of The Oracle-Brother Norman Senior Omega who have served and are still serving in the Director of Photography- Brother James Witherspoon United States Armed Emeritus Photographer-Brother John H. -

Kansans for Health Freedom Program

T H I S B O O K B E L O N G S T O : I F F O U N D , C O N T A C T I N F O . WELCOME! Welcome to the Freedom Revival in the Heartland event of 2020. We are so excited to have you here! I can assure you that getting this event off in only three weeks is a testament to the power of God working in a million big and little ways. It is also a testament to the talent, passion, and inspiration of some very dedicated and hard-working people. Today, we unite with all who are awake to the rising trend of medical tyranny. We join with those who have been silenced. We grieve with those who have lost so much. Finally, we rejoice that many more are waking up to the corruption of our health agencies and the failure of the pharma-medical paradigm every day. Kansans for Health Freedom is a young organization which came together in June of 2019. Our goal is to promote and uphold our constitutional freedoms for vaccine and medical choice and true informed consent. We want to see the needless injuries and deaths from vaccines eliminated. We want to hear the unheard and be a voice for the silenced. We want to educate the public about the very real risks of vaccines so that no more will be harmed. Our wonderful team has had an amazing year with many great learning experiences. Some of you have been a part of that, and we thank you! If you are not a member of KSHF but you believe the government and its agencies should not be the determiners for your family’s health choices, please join us. -

The Shift from Public Science Communication to Public Relations. the Vaxxed Case

BIG DATA AND DIGITAL METHODS IN SCIENCE COMMUNICATION RESEARCH: OPPORTUNITIES, CHALLENGES AND LIMITS The shift from public science communication to public relations. The Vaxxed case Davide Bennato Abstract Social media is restructuring the dynamics of science communication processes inside and outside the scientific world. As concerns science communication addressed to the general public, we are witnessing the advent of communication practices that are more similar to public relations than to the traditional processes of the Public Understanding of Science. By analysing the digital communication strategies implemented for the anti-vaccination documentary Vaxxed, the paper illustrates these new communication dynamics, that are both social and computational. Keywords Public understanding of science and technology; Science and media; Science communication: theory and models Purpose This paper aims to illustrate how science communication is changing as social media strategies are being introduced in the process of shaping public opinion, focusing on the transition from processes typical of the Public Understanding of Science to a dynamic belonging more to public relations, especially with processes leading to scientific controversies [Lorenzet, 2013]. The use of social media within science communication processes cannot be regarded simply as the introduction of a novel communication channel. It creates an actual social space [Bennato, 2011] in which to activate a controversy-structuring political dynamic. On the one hand, this is because the very nature of social platforms implies a public debate. Therefore, in the course of a controversy, it is possible to convince the public of the truth of a particular stance, although evidently in contrast to scientific evidence. On the other hand, often the strategies adopted are not logical, but rhetorical. -

An Interview with Naturopathic Doctor Matt Brignall Transcribed by Julie

How “crunchy” got crushed: An interview with naturopathic doctor Matt Brignall May 29, 2020 Transcribed by Julie Ann Lee (Theme song - soft piano music) ABK: Welcome to Noncompliant: The Podcast. I’m your host Anne Borden King. Matt Brignall is a Naturopathic Doctor in Tacoma, Washington. He currently works in a community- based, primary care practice. For nearly 20 years he was a professor in the Naturopathic training program at Bastyr University. He left because he felt that the alternative medicine community was losing its ethical bearings, and becoming a threat to individual and public health. In addition to his practice, he’s currently working as part of the Medical Reserve Corps COVID-19 response team. Matt is the parent of a 20-year-old daughter with Rett Syndrome, and is active in disability advocacy. Matt’s website NDs For Vaccines offers a wealth of information for Naturopaths as well as consumers about the safety and the need for vaccines. It’s an amazing resource. One thing I really love about Matt’s work is that he always avoids the divisive approach, like I’m thinking of SciBabe or some of these annoying ‘I love GMOs’ people, where it seems more about winning an argument than what Matt is doing. And what Matt is doing is very radical and important, influencing people to think differently – to open their minds and find common ground and languages and solutions that might not always be the solutions we want in a perfect world, but which are realistic and bring us closer to public health goals. -

Bush Disinformation • •

WfJRNERS 'ANfiIJARIJ 50¢ No. 856 , €<§::>C-701 14 October 2005 Judith Miller and Bush Disinformation • • I~~' --I!aJ. - AFP Ig les DPA an mperia isl ar Iraq today threatens to completely unr,l\el under the hlood) L.S. llL'Cupa Down With tion. More than -l-.()OO ci\ilians hale been killed in Baghdad alone since April. The U.S. Occupation number of American dead in Iraq is clo\ ing in on 2,O()(). \Vith the approal'h of tht' of Iraq! October 15 "'referendum" on the Iraqi constitution, the daily toll of car bomh OCTOBER 7-,\;,1'\\ }(II-A: Ji"IlIC,1 repl)rter ings and other deadly attacks i, inneas Judith ;'.,Jilkr \\~dked out of pri~on laq ing, as i~ the terror campaign carried out \Ieek after being held for nearly three hy C.S. forces in predominantl) Sunni months for refusing to testify before a areas. Illustrating the farcical nature nf grand jury ime,tigating the outing orCIA the "referendum:' earlier this \\ eek thc clgent Valerie Plame. The entire time, her prm isional Iraqi parliament rell rotl' ho,ses at the Tillles portra~ed -'filler as a the rules to make it all but impos<;ihle for martyr in the CIlI,C of the "frl'e pre,ss." the Sunni population, whose inten:sl'> the But in Lcd, ~hller was freed because she document makes deCided I) secondary til had promised that she would immediately those of the Shi' ites and Kurd,. to \ ok it te,tify before the grand jury. down. Thl' mO\e was quickly scuttled as \fany liberals and leftists took up U.S. -

By Jon Rappoport Vaxxed: How Did They Threaten Robert De Niro?

Jon Rappoport's Blog Vaxxed: How did they threaten Robert De Niro? by Jon Rappoport Vaxxed: How did they threaten Robert De Niro? De Niro talked to Congressman about censored Vaxxed film by Jon Rappoport March 27, 2016 (To read about Jon’s mega-collection, Power Outside The Matrix, click here (hp://marketplace.mybigcommerce.com /power-outside-the-matrix/).) “On July 26, 2000, the prestigious Journal of the American Medical Association published a review by Dr. Barbara Starfield, a revered public-health expert at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. Dr. Starfield’s review, ‘Is US health really the best in the world?’ (hp://www.drug-education.info/documents/iatrogenic.pdf), concluded that, every year in the US, the medical system kills 225,000 people. That’s 2.25 million killings per decade.” (Jon Rappoport, The Starfield Revelation (hps://jonrappoport.wordpress.com/2015/03 /06/the-starfield-revelation-medically-caused-death-in-america/)) This is explosive. This is about a film no one can see, because it exposes lunatics and destroyers in the vaccine industry. Here is a quote from the Vaxxed producer and director, after their film was just axed (hps://jonrappoport.wordpress.com /2016/03/27/the-vaccine-film-robert-deniro-wont-let-his-audience-see/) from Robert De Niro’s Tribeca Festival (as reported by Jeremy Gerard, see: “‘Vaxxed’ Filmmakers Accuse De Niro, Tribeca Film Fest Of ‘Censorship’ In Wake Of Cancelation,” (hp://deadline.com/2016/03/robert-de-niro-vaxxed-tribeca-film-festival-statement-1201726799/) 3/26/2016): “’To our dismay, we learned today about the Tribeca Film Festival’s decision to reverse the official selection of Vaxxed: From Cover-Up to Catastrophe [trailer (hps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EdCU2DfMBpU)],’ said Andrew Wakefield and Del Bigtree (the director and producer, respectively). -

NHFC Annual Report 2016

NHFC 2016 Annual Report National Health Freedom Coalition Contents What We Do 3 Our Work in 2016 4 Our Team 8 2016 Financial Statement 10 Gratitude to 2016 Donors 11 What We Do Barriers to Health Freedom Consumers have lost access to holistic health care practitioners. NHFC educates citizens as to why these events happen and what they can do about it. Licensed Practitioners practicing holistic approaches can lose their licenses for practicing outside of prevailing and accepted standards of care. Other practitioners, such as herbalists, homeopaths, traditional naturopaths and energy workers, can be prosecuted for practicing medicine without a license. Government regulations and laws are blocking people’s fundamental rights. Parents are being required to vaccinate their children before they go to daycare or school, or forced to approve chemotherapy treatments for them against their wishes. Farmers selling fresh produce from the farm are being raided. Many people needing dental care must settle for toxic mercury fillings because of government subsidies. Consumers do not have labels to tell them whether a food is GMO produced. NHFC Educating for Positive Change NHFC teaches people what health freedom is, and what they need to do to protect their health freedoms. We support citizens in forming state health freedom groups, and train them how to make the changes they want. NHFC receives a broad range of requests from citizens ranging from questions as to how a particular bill or policy might be interpreted, or requests from citizens who have become aware that their practitioner or healing arts business has been shut down, or citizens that want to know how to protect their right to decline vaccines, or their right to obtain fresh raw milk or organic produce from a farm, or their right to parent their child without intervention from Child Protective Services, and much more. -

Thesis Template

WHY DO WE ARGUE ABOUT SCIENCE? EXPLORING THE PSYCHOLOGICAL ANTECEDENTS OF REJECTION OF SCIENCE JOHN RICHARD KERR A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington for the fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2020 Abstract Science is recognised and accepted as an important tool for understanding the world in which we live, yet some people hold beliefs that go against the best available scientific evidence. For example, many people believe human-caused climate change is not occurring, or that vaccines are ineffective and dangerous. Previous research has investigated a range of possible drivers of this ‘rejection of science’ (Lewandowsky, Oberauer, & Gignac, 2013), including ignorance, distrust of scientists, and ideological motivations. The studies in this thesis extend this line of inquiry, focusing first on the role of perceptions of scientific agreement. I report experimental evidence that people base their beliefs on ‘what they think scientists think’ (Study 1). However, an analysis of longitudinal data (Study 2) suggests that our personal beliefs may also skew our perceptions of scientific agreement. While the results of Study 1 and Study 2 somewhat conflict, they do converge on one finding: perceptions of consensus alone do not fully explain rejection of science. In the remainder of the thesis I cast a wider net, examining how ideological beliefs are linked to rejection of science. Study 3 draws on social media data to reveal that political ideology is associated with rejection of science in the context of who people choose to follow on the platform Twitter. A final set of studies (4, 5, and 6) examine the role of two motivational antecedents of political ideology, Right-wing Authoritarianism (RWA) and Social Dominance Orientation (SDO), in rejection of science across five publicly debated issues.