Planetary Exploration in Extremis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission to Jupiter

This book attempts to convey the creativity, Project A History of the Galileo Jupiter: To Mission The Galileo mission to Jupiter explored leadership, and vision that were necessary for the an exciting new frontier, had a major impact mission’s success. It is a book about dedicated people on planetary science, and provided invaluable and their scientific and engineering achievements. lessons for the design of spacecraft. This The Galileo mission faced many significant problems. mission amassed so many scientific firsts and Some of the most brilliant accomplishments and key discoveries that it can truly be called one of “work-arounds” of the Galileo staff occurred the most impressive feats of exploration of the precisely when these challenges arose. Throughout 20th century. In the words of John Casani, the the mission, engineers and scientists found ways to original project manager of the mission, “Galileo keep the spacecraft operational from a distance of was a way of demonstrating . just what U.S. nearly half a billion miles, enabling one of the most technology was capable of doing.” An engineer impressive voyages of scientific discovery. on the Galileo team expressed more personal * * * * * sentiments when she said, “I had never been a Michael Meltzer is an environmental part of something with such great scope . To scientist who has been writing about science know that the whole world was watching and and technology for nearly 30 years. His books hoping with us that this would work. We were and articles have investigated topics that include doing something for all mankind.” designing solar houses, preventing pollution in When Galileo lifted off from Kennedy electroplating shops, catching salmon with sonar and Space Center on 18 October 1989, it began an radar, and developing a sensor for examining Space interplanetary voyage that took it to Venus, to Michael Meltzer Michael Shuttle engines. -

Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science

MaRS: Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science M. Pätzold1, F.M. Neubauer1, L. Carone1, A. Hagermann1, C. Stanzel1, B. Häusler2, S. Remus2, J. Selle2, D. Hagl2, D.P. Hinson3, R.A. Simpson3, G.L. Tyler3, S.W. Asmar4, W.I. Axford5, T. Hagfors5, J.-P. Barriot6, J.-C. Cerisier7, T. Imamura8, K.-I. Oyama8, P. Janle9, G. Kirchengast10 & V. Dehant11 1Institut für Geophysik und Meteorologie, Universität zu Köln, D-50923 Köln, Germany Email: [email protected] 2Institut für Raumfahrttechnik, Universität der Bundeswehr München, D-85577 Neubiberg, Germany 3Space, Telecommunication and Radio Science Laboratory, Dept. of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 95305, USA 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasadena, CA 91009, USA 5Max-Planck-Instuitut für Aeronomie, D-37189 Katlenburg-Lindau, Germany 6Observatoire Midi Pyrenees, F-31401 Toulouse, France 7Centre d’etude des Environnements Terrestre et Planetaires (CETP), F-94107 Saint-Maur, France 8Institute of Space & Astronautical Science (ISAS), Sagamihara, Japan 9Institut für Geowissenschaften, Abteilung Geophysik, Universität zu Kiel, D-24118 Kiel, Germany 10Institut für Meteorologie und Geophysik, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, A-8010 Graz, Austria 11Observatoire Royal de Belgique, B-1180 Bruxelles, Belgium The Mars Express Orbiter Radio Science (MaRS) experiment will employ radio occultation to (i) sound the neutral martian atmosphere to derive vertical density, pressure and temperature profiles as functions of height to resolutions better than 100 m, (ii) sound -

MARS an Overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera Science

MARS MARS INFORMATICS The International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration Open Access Journals Science An overview of the 1985–2006 Mars Orbiter Camera science investigation Michael C. Malin1, Kenneth S. Edgett1, Bruce A. Cantor1, Michael A. Caplinger1, G. Edward Danielson2, Elsa H. Jensen1, Michael A. Ravine1, Jennifer L. Sandoval1, and Kimberley D. Supulver1 1Malin Space Science Systems, P.O. Box 910148, San Diego, CA, 92191-0148, USA; 2Deceased, 10 December 2005 Citation: Mars 5, 1-60, 2010; doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0001 History: Submitted: August 5, 2009; Reviewed: October 18, 2009; Accepted: November 15, 2009; Published: January 6, 2010 Editor: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University Reviewers: Jeffrey B. Plescia, Applied Physics Laboratory, Johns Hopkins University; R. Aileen Yingst, University of Wisconsin Green Bay Open Access: Copyright 2010 Malin Space Science Systems. This is an open-access paper distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: NASA selected the Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) investigation in 1986 for the Mars Observer mission. The MOC consisted of three elements which shared a common package: a narrow angle camera designed to obtain images with a spatial resolution as high as 1.4 m per pixel from orbit, and two wide angle cameras (one with a red filter, the other blue) for daily global imaging to observe meteorological events, geodesy, and provide context for the narrow angle images. Following the loss of Mars Observer in August 1993, a second MOC was built from flight spare hardware and launched aboard Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) in November 1996. -

Absolute Transmetropolitan Vol. 2 Online

gWHNU (Mobile pdf) Absolute Transmetropolitan Vol. 2 Online [gWHNU.ebook] Absolute Transmetropolitan Vol. 2 Pdf Free Warren Ellis ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF #486638 in Books Warren Ellis 2016-05-24 2016-05-24Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 15.00 x 2.40 x 9.80l, .0 #File Name: 1401261159560 pagesAbsolute Transmetropolitan Volume 2 | File size: 34.Mb Warren Ellis : Absolute Transmetropolitan Vol. 2 before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Absolute Transmetropolitan Vol. 2: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Great graphic novel a must buyBy Kevin A SparksGreat graphic novel a must buy. I can't wait for the 3rd final Volume to complete the collection.4 of 6 people found the following review helpful. Get itBy A LI preordered this book September 17, 2015. Wow, a long time ago, says you, a person reading this review. No s***, say I, a person who did the waiting. Second time is just as beautiful as the first. 10/10, will preorder the third one.0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. One of the best!By FredstrongThis one of the best comics of all time. Darkly humorous, insightful social commentary, amazing artwork. Like Hunter S. Thompson before him, Spider Jerusalem is a hero for our times. Warren Ellis and Darick Robertsonrsquo;s masterwork of gonzo science fiction and political soothsaying is finally available in a majestic Absolute Edition mdash; just as Nostradamus predicted! As vital and engaging today as when it first hit the stands, the weaponized viral meme that is TRANSMETROPOLITAN occupies the toxic quagmire that runs between the burning wreckage of print journalism and the repellent echo chamber of online media. -

Icons of Survival: Metahumanism As Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture

Lioi, Anthony. "Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense." Nerd Ecology: Defending the Earth with Unpopular Culture. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 169–196. Environmental Cultures. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474219730.ch-007>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 20:32 UTC. Copyright © Anthony Lioi 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 6 Icons of Survival: Metahumanism as Planetary Defense In which I argue that superhero comics, the most maligned of nerd genres, theorize the transformation of ethics and politics necessary to the project of planetary defense. The figure of the “metahuman,” the human with superpowers and purpose, embodies the transfigured nerd whose defects—intellect, swarm-behavior, abnormality, flux, and love of machines—become virtues of survival in the twenty-first century. The conflict among capitalism, fascism, and communism, which drove the Cold War and its immediate aftermath, also drove the Golden and Silver Ages of Comics. In the era of planetary emergency, these forces reconfigure themselves as different versions of world-destruction. The metahuman also signifies going “beyond” these economic and political systems into orders that preserve democracy without destroying the biosphere. Therefore, the styles of metahuman figuration represent an appeal to tradition and a technique of transformation. I call these strategies the iconic style and metamorphic style. The iconic style, more typical of DC Comics, makes the hero an icon of virtue, and metahuman powers manifest as visible signs: the “S” of Superman, the tiara and golden lasso of Wonder Woman. -

Towards a Sustainable Modular Robot System for Planetary Exploration S

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Mechanical (and Materials) Engineering -- Mechanical & Materials Engineering, Department Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research of 4-2014 TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE MODULAR ROBOT SYSTEM FOR PLANETARY EXPLORATION S. G. M. Hossain University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mechengdiss Part of the Applied Mechanics Commons, Electro-Mechanical Systems Commons, Other Astrophysics and Astronomy Commons, and the Robotics Commons Hossain, S. G. M., "TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE MODULAR ROBOT SYSTEM FOR PLANETARY EXPLORATION" (2014). Mechanical (and Materials) Engineering -- Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research. 69. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/mechengdiss/69 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mechanical & Materials Engineering, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mechanical (and Materials) Engineering -- Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE MODULAR ROBOT SYSTEM FOR PLANETARY EXPLORATION by S. G. M. Hossain A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics Under the Supervision of Professor Carl A. Nelson Lincoln, Nebraska April, 2014 TOWARDS A SUSTAINABLE MODULAR ROBOT SYSTEM FOR PLANETARY EXPLORATION S. G. M. Hossain, Ph. D. University of Nebraska, 2014 Advisor: Carl A. Nelson This thesis investigates multiple perspectives of developing an unmanned robotic system suited for planetary terrains. In this case, the unmanned system consists of unit-modular robots. -

Growing up with Vertigo: British Writers, Dc, and the Maturation of American Comic Books

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ScholarWorks @ UVM GROWING UP WITH VERTIGO: BRITISH WRITERS, DC, AND THE MATURATION OF AMERICAN COMIC BOOKS A Thesis Presented by Derek A. Salisbury to The Faculty of the Graduate College of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Specializing in History May, 2013 Accepted by the Faculty of the Graduate College, The University of Vermont, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, specializing in History. Thesis Examination Committee: ______________________________________ Advisor Abigail McGowan, Ph.D ______________________________________ Melanie Gustafson, Ph.D ______________________________________ Chairperson Elizabeth Fenton, Ph.D ______________________________________ Dean, Graduate College Domenico Grasso, Ph.D March 22, 2013 Abstract At just under thirty years the serious academic study of American comic books is relatively young. Over the course of three decades most historians familiar with the medium have recognized that American comics, since becoming a mass-cultural product in 1939, have matured beyond their humble beginnings as a monthly publication for children. However, historians are not yet in agreement as to when the medium became mature. This thesis proposes that the medium’s maturity was cemented between 1985 and 2000, a much later point in time than existing texts postulate. The project involves the analysis of how an American mass medium, in this case the comic book, matured in the last two decades of the twentieth century. The goal is to show the interconnected relationships and factors that facilitated the maturation of the American sequential art, specifically a focus on a group of British writers working at DC Comics and Vertigo, an alternative imprint under the financial control of DC. -

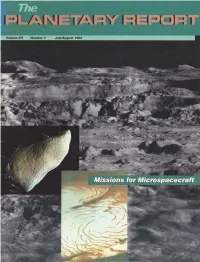

The Planetary Report (Lssn 0736-3680) Is Published Six Times Yearly at Dozens of People Clamoring to Come

A Publication of THEPLANETA SOCIETY o ¢ 0 0 o o • 0-e Board of Directors FROI\II THE CARL SAGAN BRUCE MURRAY EDITOR President Vice President Director. Laboratory for Planetary Professor of Planetary Studies. Cornell University Science, California Institute of Technology LO UIS FR IEDMAN Executive Director JOSEPH RYAN O'Me/veny & Myers MICHAEL COLLINS Apollo 11 astronaut STEVEN SPIELBERG . he way we explore planets is chang its 1994 budget a new Discovery class of director and producer THOMAS O. PAINE former Administrator, NASA; HENRY J. TANNER T ing. Gone are the days when we could missions to cost no more than $150 mil Chairman, National financial consultant Commission on Space build space-traveling, multipurpose vehi lion each and to be accomplished in three Board of Advisors cles, load them with a profusion of years or less. Whether or not Congress instruments and send them off to answer will fund these missions remains to be DIANE ACKERMAN HANS MARK poet and author Chancellor. a multitude of scientific questions. seen. University of Texas System RICHARD BERENDZEN The Cassini mission to the saturnian Meanwhile, there are other concepts for educator and astrophysicist JAMES MICHENER author system, if it survives the congressional small spacecraft missions, many of which JACQUES BLAMONT Chief Scientist. Centre MARVIN MINSKY budget process, will probably be the last grew out of papers presented at the Soci National dEludes Spatia/es. France Toshiba Professor of Media Arts and Sciences, Massachusetts "flagship" mission launched for a long ety's workshop. Rather than bring you RAY BRADBURY Institute of Technology poet and author time. -

Register Free to Download Files | File Name : the Planetary Omnibus PDF

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : The Planetary Omnibus PDF THE PLANETARY OMNIBUS Tapa dura Ilustrado, 4 febrero 2014 Author : Warren Ellis Descripcin del productoContraportadaHailed as a timeless story that turned modern super hero conventions on their heads, PLANETARY stars an inter-dimensional peace-keeping force including Elijah Snow, Jakita Wagner, and The Drummer. Tasked with tracking down evidence of super-human activity, these mystery archaeologists uncover unknown paranormal secrets and histories, such as a World War II supercomputer that can access other universes, a ghostly spirit of vengeance, and a lost island of dying monsters. Now, the entire series is collected in hardcover, including PLANETARY #1-27, PLANETARY/BATMAN #1, PLANETARY/JLA #1 and PLANETARY/AUTHORITY #1. Biografa del autorWarren Ellis is a prolific writer whose works include the novel Crooked Little Vein (William Morrow) and, for Marvel Comics, Iron Man, Nextwave, Newuniversal and many others. His work for DC Comics includes Planetary, Red, Stormwatch, Ocean, Global Frequency, Hellblazer, and a five-year run on Transmetropolitan. Book in poor condition No criticism of the stories contained in this omnibus edition, they are entertaining in the extreme. Ellis and Cassaday have created an amazing meta-textual adventure in Planetary.However, and I hate leaving negative feedback, the copy that I received has crushed corners front and back. I will be returning this copy so that bored Amazon staff can continue their game of five-a-side football with it. Disappointed. Absolutely phenomenal. An underrated piece of work by Ellis. . -

Vector 259 Harrison 2009-Sp

Vector 258 Contents Torque Control President Stephen Baxter Letters l Chair Tony Cullen 2009 Vector Reviewers PoD Edited by KariSperring cIu.UObsfa.co.uk You Sound Like You're Having Fun Already Treaswer Martin Potts The SF Films of 2008 16 61 Ivy Croft Road. Warton By Colin Odell and Mitdt Le Blanc Near Tamworth Progressive Scan: 2008 TV in Review 23 B'790n mtpottsOzoom.co.uk by Abigail Nussbaum Membership First Impressions 28 Services Peter WiJkin80n Book Reviews edited by Kari Sperring Resonances: Column 154 43 ~~~~':;. New Bamet by Stcphcn Baxter bslamembershipOyahoo.co.uk Foundation's Favourites: The Amba~dor 4S Membership fees By Andy Sawyer The New X: Edge Detector 47 UK ~b;·~:::ti~~ps) By Graham Sleight Outside UK £32 Celebrating 30 years of Luther Arkwright 50 Bryan Talbot in discussion with James Bacon The BSFA was founded in 1958 and is a non-proBtmaldng BSFA Award Shortlists 2008 52 organisation entiWy sta~ by unpaid volunteers. Registered in England. Limited by guarantee. Company No. 921.500 V-.w.bQtehttp-JIwww.~uk Registered address: 61 Ivy Croft Road, Wartoa,. Near Tamworth.B'790JJ Editnfs blog: http-Jlvedoreditn...wonlpress.rom Website http://www.bsfa.co.ulc Vector Orbiter writing groupS Features, Editorial and Letters: Niall Hartison Postal GUlian Rooke Southview, Pilgrims Lane 73 Sunderland Avenue 0tiIham, Kent Oxford cr48AB 0X28DT Online Terry Jackman Book Reviews: Kari Spening terryjadanan«mypostoffice.co.uk 19UphaU Road Other BSFA publications Cambridge Focus: The writers magazine of the BSFA CB13HX Editor Martin McGrath Production: Liz Batty 48 Spooners Drive. emb510cam.acuk ""'Street.StAlbans,. A1.22HL Anna Feruglio Dal Oan focusmagazinecPntlworld.com annafdd8gmail.com Matrix: The news magazine of the BSFA Editor tan Whates finiangOaoJ.rom Publ.it.bedbythe.SJ'A~ISSNQ!iQ5CN.U All opWoN UI ttt- of Ilw ind.iridual UIJItributDn and u-.w nut PrintedbyI'OCCopyprinI(Cuillord).~Unit,.71..!3Wa1nuITrft .--riIybetUcn uth~..w-oftheSSFA. -

Advisory Panel and Staff

annual report to the nasa administrator by the aerosoaceI safetv advisoryn 0 panel I - 4km-A volume II the apollo soyuz test project and the space shuttle program march 1974 ’ / / .- AEROSPACE SAFETY ADVISORY PANEL AND STAFF Howard K. Nason (Chairman) President Monsanto Research Corporation St. Louis, Missouri Dr. Harold M. Agnew Dr. Henry Reining Director Dean Fmeritus and Special Assis- Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory tant to the President University of California University of Southern California Los Alamos, New Mexico Los Angeles:, California Hon. Frank C. Di Luzio Dr. Ian M. Ross Science Advisor to the Vice President, Network Planning Governor of New Mexico and Consumer Services State House Bell Laboratories Santa Fe, New Mexico Holmdel, New Jersey Mr. Herbert E. Grier Lt. Gen. Warren D. Johnson, USAF Senior Vice Present Director EG&G, Inc. Defense Nuc:Lear Agency Las Vegas, Nevada Washington, D.C. Mr. Lee R. Sherer Director NASA Flight Research Center Edwards, California CONSULTANTSAND STAFF Mr. Bruce T. Lundin (Consultant) Dr. William A. Mrazek (Consultant) Director Former Director of Engineering NASA Lewis Research Center NASA Marshall Space Flight Center Cleveland, Ohio Huntsville, Alabama Mr. Gilbert L. Roth Mr. Carl R. Praktish Special Assistant Executive Secretary NASA Headquarters NASA Headquarters Washington, D.C. Washington, D.C. Mrs. V. Eileen Evans Administrative Specialist NASA Headquarters Washington, D.C. D B = 0 - rr .- ANNUAL REPORT TO THE NASA ADMINISTRATOR by the AEROSPACE SAFETY ADVISORY PANEL VOLUME II - THE APOLLO SOYUZ TEST PROJECT AND THE SPACE SHUTTLE PROGRAM March 1974 PREFACE This volume (II) recognizes the need for specific background information and supporting details to round out and extend the data provided in vol- ume I of this report by the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel. -

Planetary Defense Final Report I

Team Project - Planetary Defense Final Report i Team Project - Planetary Defense Final Report ii Team Project - Planetary Defense Cover designed by: Tihomir Dimitrov Images courtesy of: Earth Image - NASA US Geological Survey Detection Image - ESA's Optical Ground Station Laser Tags ISS Deflection Image - IEEE Space Based Lasers Collaboration Image - United Nations General Assembly Building Outreach Image - Dreamstime teacher with students in classroom Evacuation Image - Libyan City of Syrte destroyed in 2011 Shield Image - Silver metal shield PNG image The cover page was designed to include a visual representation of the roadmap for a robust Planetary Defense Program that includes five elements: detection, deflection, global collaboration, outreach, and evacuation. The shield represents the idea of defending our planet, giving confidence to the general public that the Planetary Defense elements are reliable. The orbit represents the comet threat and how it is handled by the shield, which represents the READI Project. The curved lines used in the background give a sense of flow representing the continuation and further development for Planetary Defense programs after this team project, as we would like for everyone to be involved and take action in this noble task of protecting Earth. The 2015 Space Studies Program of the International Space University was hosted by the Ohio University, Athens, Ohio, USA. While all care has been taken in the preparation of this report, ISU does not take any responsibility for the accuracy of its content.