Deep-Green Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring Catalog 20082008 OLLI • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE Formerly Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL)

PARTNERS IN EDUCATION WITH WILLIAMS COLLEGE BARD COLLEGE AT SIMON’S ROCK MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AT BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE www.BerkshireOLLI.org • 413.236.2190 Spring Catalog 20082008 OLLI • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute AT BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE Formerly Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL) WELCOME TO OLLI AT BCC The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) at Berkshire Community College was established in 2007 following a grant from the Bernard Osher Foundation of San Francisco to the Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL). Founded in 1994 as a volunteer-run organization, BILL fostered lifelong learning opportunities for adults in the culture-rich Berkshire area. Building on this tradition, OLLI continues the classes, trips, special events and lectures that members value. As part of the nationwide OLLI network, members can enjoy educational resources, ideas and advanced technologies that offer an even wider range of learning. In addition to Berkshire Community College, OLLI is a partner in education with Williams College, Bard College at Simon’s Rock and Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and has cultural partners including the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. These institutions give generously of their faculty and facilities to enrich the lifetime learning of OLLI members. N Choose from among 50-plus (noncredit) courses in a variety of subject areas offered in the fall, winter, spring and summer semesters. N Attend distinguished speaker lectures and panel discussions that stimulate and inform. N Experience history and culture through special events and trips. N Network with other members to form groups of mutual interest. LEARN – EXPLORE – ENJOY JOIN OLLI UPCOMING EVENTS AND LECTURES March . -

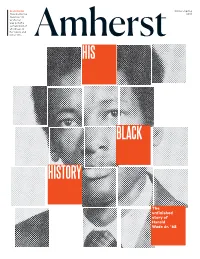

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

Williamstown and Williams College: Explorations in Local History

WILLIAMSTOWN and WILLIAMS COLLEGE Explorations in Local History dustin griffin WILLIAMSTOWN and WILLIAMS COLLEGE This page intentionally left blank WILLIAMSTOWN and WILLIAMS COLLEGE Explorations in Local History DUSTIN GRIFFIN BRIGHT LEAF AMHERST AND BOSTON An imprint of University of Massachusetts Press Copyright © 2018 by University of Massachusetts Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978- 1- 62534- 379- 6 (paper); 378- 9 (hardcover) Designed by Sally Nichols Set in Perpetua Titling and Adobe Garamond Pro Printed and bound by Maple Press Inc. Cover design by Rebecca S. Neimark, Twenty-Six Letters Cover art: Detail from Bird’s- Eye View of Main St., Looking West. Photogravure, W. T. Littig & Company, New York, 1906. Courtesy of the Williams College Museum of Art and College Archives and Special Collections, Williams College. Publication of this book has been aided by a grant from the Abraham and Rebecca Stein Publication Fund of New York University, Department of English. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Griffin, Dustin H., author. Title: Williamstown and Williams College : explorations in local history / Dustin Griffin. Description: Amherst : University of Massachusetts Press, [2018] | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018020569 (print) | LCCN 2018024453 (ebook) | ISBN 9781613766262 (e-book) | ISBN 9781613766279 (e-book) | ISBN 9781625343789 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781625343796 (pbk.) Subjects: LCSH: Williams College—History. | Williamstown (Mass.)—History. | Local history—Massachusetts—Williamstown. Classification: LCC LD6073 (ebook) | LCC LD6073 .G75 2018 (print) | DDC 378.744/1—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018020569 British Library Cataloguing- in- Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Broadcasting Un

Supreme Court again upholds an FCC cable stand Special report on MOR radio: a specialty all its own BroadcastingThe newsweekly of broadcasting and allied arts unOur 41st Year 1972 Because 12 stations are winning with"Moat's My Line?" in prince time light now, 13 more stations are putting "Miiat's My Line ?" in prime time this Fall. Sometimes, the best way to lead is to follow. Source: NSI,Feb:Mor. 1972. Audience estimates are subject to qualifications on request. !Number of time merited wine i< kneed nn me..n.....,n.......A i..... ... I He's one of the thousands of like him, WPTV's Public Affairs De- At Scripps- Howard, we see Spanish- speaking migrants and partment arranged for a series of a great future for this .kind of immigrants who live in South unique simulcasts, with the cooper- communication link -up. We see Florida. Which meant he was cut ation of a local educational radio it as a part of our constant ef- off from coverage of major news station, WHRS -FM. These broad- fort to inform and involve every events because of the language casts made it possible to watch the minority. Every person. And barrier. Apollo 16 launch on TV while lis- we figure that's real community To bring the world a little tening to a simultaneous transla- service -in any language. closer home to Miguel and others tion into Spanish on radio. The Scripps- Howard Broadcasting Co. WEWS (TV) Cleveland, WCPO -TV Cincinnati, WMC, WMC -FM, s Palm Beach WNOX Knoxville. BroadcastingmJun12 CLOSED CIRCUIT 5 FCC's domestic satellite policy about set. -

The Educational Radio Media

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Theatre Arts, School of 1969 The Educational Radio Media James L. Tungate '69 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/theatre_honproj Part of the Speech and Rhetorical Studies Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Tungate '69, James L., "The Educational Radio Media" (1969). Honors Projects. 12. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/theatre_honproj/12 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Illinois Wesleyan University ARCHIVES 3 36 192�b� The Edgcational Radio Media / James L. Tgngate II Submitted for Honors Work In the Department of Speech Illinois Wesleyan University Bloomington, Illinois 1969 w.rttnoIn Wesleyan Unl'v. tTOrarI'o Eloomington, Ill. 61701 Accepted by the Department o� Speech of Illinois Wesleyan University in Yalfillment of the requirement for Departmental Honors Date TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TA BLES. • • • • • • • •• • co • • . .. • • • iv LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS • • co • • • • • .. • co • • co • • v .. .. 1 INTRODUCTION. -

How to Write for Williams Last Updated July 2007

How to Write for Williams Last updated July 2007 Editorial style makes writing easier for writers, editing easier for editors and reading easier for readers. The goal of this style guide is to provide clear, simple guidelines for you, the writer, on grammar, punctuation, spelling and usage in materials produced by and for Williams College. In most instances, our style is based on the Associated Press (AP) Stylebook, 2000 ed., and Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed. It was developed by the Alumni Review in consultation with the Office of Public Affairs and the Office of Alumni Relations and Development. The style guide is organized alphabetically. If you have questions or items to be added, contact the Alumni Review at 413.597.4278 or by e-mail at [email protected]. academic courses The formal names of academic courses should be capitalized and in quotation marks: She took “Fundamentals of Modern Literature.” Informal names of courses should be capitalized but do not need quotation marks: Psych 101, Intro Psych. See capitalization; course titles; titles of things. academic degrees Avoid using abbreviations (except in Class Notes). Instead: Judy Smith is studying for a master’s degree (generic); He received a master’s in geology (specific). Do not use PhD as a noun (except in Class Notes). Instead: She completed a doctorate in May. Lowercase cum laude, magna cum laude, with honors. See capitalization. a cappella abbreviations/acronyms Well-known acronyms and common abbreviations of names should be formed without periods: CEO, CIA, FBI, GPA, NATO and SAT. VP is acceptable for vice president in class notes. -

Affidavit of R Boulay Re Voiding of Emergency Broadcast Sys Ltrs of Agreement.* Since WCGY Voided Ltr of Agreement W

c. b L . o | | I | r UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) < NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION q > 1 ATOMIC SAFETY AND LICENSING BOARD I u- Before the Administrative Judges: Ivan W. Smith, Chairman Dr. Richard F. Cole Kenneth A. McCollom j 1 | = | ) I In the Matter of ) Docket Nos. 50-443-OL | ) 50-444-OL L -PUBLIC SERVICE COMPANY ) OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, EI AL. | ) , | ) 1 (Seabrook Station, Units 1 and 2) November 9, 1989 ) ' ) 1 | | AFFIDAVIT OF ROBERT BOULAY REGARDING l | THE VOIDING OF THE EBS LETTERS OF AGREEMENT ; 1 1 I, Robert Boulay, being duly sworn, state'as follows: | | | 1. I am the Director of the Massachusetts Civil Defense | . Agency. My' office is located at the Massachusetts Civil Defense Headquarters, 400 Worcester Road, Framingham, Massachusetts. As | I Director of the Massachusetts Civil Defense Agency I am the 1 official who is ultimately responsible for the supervicion and oversight of the Massachusetts Emergency Broadcast System | ! ("EBS"), and am familiar with its purposes, configuration, and ! l operation. The Communications / Warning Officer who is the official who is primarily responsible for the oversight and hand on maintenance of the Massachusetts Emergency Broadcast System j 1 0911160009 891109 : PDR ADOCK 05000443 1 0 PDR - - - - ~_. - - . _ - _ _ _ . - - . - _ . - . - . - - -. ("EBS") reports directly to me and I supervise his activities as part of my job responsibilities. I have been Director of the Massachusetts civil Defense Agency for approximately seven (7) years and I have worked in the field of civil defense and , emergency planning for approximately twenty-six (26) years. A copy of my professional qualifications is provided. -

1999 NESCAC Football Guide

1999 NESCAC Football Media Guide 1999 New England Small College Athletic Conference SID Directory Amherst College Middlebury College Mailing Address: P.O. Box 5000 Mailing Address: Route 30 Amherst, Mass. 01002 Middlebury, VT 05753 SID: Sarah Lukaska SID: Brad Nadeau Office Phone: (413) 542-2390 Office Phone: (802) 443-5193 Office Fax: (413) 542-2527 Office Fax: (802) 443-2529 Home Phone: TBA Home Phone: (802) 388-6705 Press Box Phone: (413) 542-2023 Press Box: (802) 443-5524 Bates College Trinity College Mailing Address: 141 Nichols Street Mailing Address: 79 Vernon Street Lewiston, ME 04240 Hartford, CT 06106 SID: Adam Levin SID: Dave Kingsley Office Phone: (207) 786-6411 Office Phone: (860) 297-2137 Office Fax: (207) 786-6484 Office Fax: (860) 297-2312 Home Phone: (207) 783-7854 Home Phone: (203) 281-6775 Press Box Phone: (207) 786-6411 Press Box: (860) 987-6202/6203 Bowdoin College Tufts University Mailing Address: Office of Communications Mailing Address: Cousens Gymnasium Brunswick, ME 04011 Medford, MA 02155 SID: Jac Coyne SID: Paul Sweeney Office Phone: (207) 725-3254 Office Phone: (617) 627-3586 Office Fax: (207) 725-3003 Office Fax: (617) 627-3516 Home Phone: (207) 729-5109 Home Phone: (978) 658-3095 Press Box Phone: (207) 725-7532 Press Box: (617) 627-3504 Colby College Wesleyan University Mailing Address: Mayflower Hill Drive Mailing Address: Freeman Athletic Center Waterville, ME 04901 Middletown, CT 06459 SID: TBA SID: Brian Katten Office Phone: (207) 872-3769 Office Phone: (860) 685-2887 Office Fax: (207) 872-3053 Office Fax: (860) 685-2691 Home Phone: TBA Home Phone: (860) 344-1046 Press Box Phone: (207) 872-3360 Press Box: (860) 685-5309 Hamilton College Williams College Mailing Address: 198 College Hill Road Mailing Address: P.O. -

Jones-Log-10-OCR-Page-0031.Pdf

Gloucester MICHIGAN Grand Haven Orchard Lake WVCA-FM 104.9 Ad nan WGHN-FM 92.l * WBLD 89.3 Greenfield WLEN 103.9 M Grand Rapids Owosso WHAi-FM 98.3 * WVAC 88 l * WCSG 91.3 § WOAP-FM 103.9 Haverhill Albion § WFUR-FM 102.9 Petoskey § WHAV-FM 92.5 t WUFN 96 7 § WGRD-FM 97 9 WJML-FM 98.9 Hyannis Alma § WJFM 93.7 § WMBN-FM 96.7 § WCOD 106. l WFYC-FM 104.9 WLAV-FM 96.9 F Plymouth 89.3 Lawrence Alpena §WOOD-FM 105.7 * WSDP 93.7 WCGW WATZ-FM 93.5 *WVGR 104.l Port 107.l Lowell WHSB 107.7 §WYON 101.3 § 91.5 91.9 §* WLTI Ann Arbor WZZM-FM 95.7 * WORW 99.5 * WSGR-FM 91.3 § WSSH F t* WCBN-FM 89.5 Greenville Royal Oak Lynn § WNRZ 102.9 D WP LB-FM 107.3 1017 * WOAK 89.3 § WLYN-FM WPAG-FM 107.l Hancock Saginaw Maynard *WUOM 917 WM PL-FM 93.5 *WAVM 91 7 § WKCQ 98. l Auburn Hamson Medford § WSBM 106.3 § wsvc 99 7 t WKKM 92.l *WMFO 91.5 t wwws 107.l Bad Axe Hastings WWEL-FM 107 9 Sandusky WLEW-FM 92 l WBCH-FM 100.l Milton WMIC-FM 97.7 Battle Creek Highland Park t* WMLN-FM 91 5 Sault Ste. Mane t§ 95.3 * WHPR 88.l New Bedford WSMM 99.5 WK FR-FM 103.3 F Hillsdale WGCY 97 3 Bay City WCSR-FM 92.l WMYS 98 1 88.3 * WCHW-FM 91.3 Holland Newbury § WGER-FM 102 5 § WHTC-FM 96.l *WQU 88 7 * 89.3 § WHNN 96.l F WJBL-FM 94 5 Newton St. -

List of Radio Stations in Massachusetts

Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Wikipedia List of radio stations in Massachusetts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Main page The following is a list of the FCC-licensed radio stations in the United States Commonwealth of Contents Massachusetts, which can be sorted by their call signs, frequencies, cities of license, licensees, Featured content and programming formats. Current events Random article Call City of License Frequency Licensee [1] Format[citation needed] Donate to Wikipedia sign [1][2] Wikipedia store WAAF 107.3 FM Westborough Entercom License, LLC Active rock Interaction Carter Broadcasting WACE 730 AM Chicopee Christian radio Help Corporation About Wikipedia WACF- Community portal 98.1 FM Brookfield A.P.P.L.E. Seed, Inc. Variety Recent changes LP Contact page Red Wolf Broadcasting WACM 1270 AM Springfield Oldies Tools Corporation What links here WAEM- 94.9 FM Acton Town of Acton, Massachusetts Variety Related changes LP Upload file WAIC 91.9 FM Springfield American International College College radio Special pages open in browser PRO version Are youWAIY- a developer? Try out the HTML to PDF API pdfcrowd.com Permanent link WAIY- 107.7 FM Belchertown Dwight Chapel Inc. Religious Teaching Page information LP Wikidata item WAMG 890 AM Dedham Gois Broadcasting Boston LLC Spanish Cite this page WAMH 89.3 FM Amherst Trustees of Amherst College College radio Print/export Great Create a book WAMQ 105.1 FM WAMC Public radio Barrington Download as PDF Printable version Saga Communications of New WAQY 102.1 FM Springfield Classic rock England, LLC In other projects Attleboro Access Cable Wikimedia Commons WARA 1320 AM Attleboro Talk/Oldies Systems, Inc. -

17Thpresident WILLIAMST

A L U MNI REVIEW January 2010 williams’ PRESIDENT 1 | WILLIAMS ALUMNI REVIE W | SP R ING 2005 17th 20 26 ALUMNI REVIEW Volume No. 104, Issue No. 4 Editor Student Assistant Amy T. Lovett Cortni Kerr ’10 Assistant Editor Design & Production departments Jennifer E. Grow Jane Firor & Associates LLC Editorial Offices P.O. Box 676, Williamstown, MA 01267-0676, tel: 413.597.4278, Opinions & Expressions fax: 413.597.4158, e-mail: [email protected], web: http://alumni.williams. edu/alumnireview Interim President Bill Wagner Address Changes/Updates Bio Records, 75 Park St., Williamstown, MA 01267-2114, reports from the field. … English tel: 413.597.4399, fax: 413.458.9808, e-mail: [email protected], web: http://alumni.williams.edu/updatemyprofile Prof. Bob Bell on his late colleague Williams magazine (USPS No. 684-580) is published in August, September, December, Fred Stocking’s ’36 intelligent January, March, April and June and distributed free of charge by Williams College for the Society of Alumni. Opinions expressed in this publication may not necessarily reflect those delight. … Letters from readers. 4 of Williams College or of the Society of Alumni. Periodical postage paid at Williamstown, MA 01267 and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to Williams magazine, 75 Park St., Williamstown, Scene & Herd MA 01267-2114 News of Williams and beyond. 6 WILLIAMS COLLEGE Board of Trustees Bill Wagner, Interim President • Gregory M. Avis ’80, Chairman of the Life of the Mind Board • Keli Kaegi, Secretary to the Board Political Science Prof. James McAllister César J. Alvarez ’84 • Barbara A. -

Winter 2005 Volume 76, Number 2

BOWDOINWinter 2005 Volume 76, Number 2 The Mind of a Goalie winter2005 contents The View From the Crease 18 By Mel Allen Photographs by Bob Handelman Sports fans agree — there’s something different about goalies, some way of looking at the game, or even the world, that only they have. Mel Allen takes an in-depth look at how men’s ice hockey goalie George Papachristopolous ’06 handles the pressure, and we talk to other Bowdoin goalies about their rituals, pre-game routines, and other tricks of the goalie trade. Joining in the Dance 28 By Selby Frame Photographs by James Marshall In the years since she arrived on campus to help Bowdoin begin a dance program in the early days of co-education, Professor of Dance June Vail has built one of the most inclusive, welcoming, and vibrant dance programs around. Climate Change in the Arctic: Is Bowdoin’s Mascot Headed for a Meltdown? 32 By Douglas McInnis Illustrations by John Bowdren The polar bear population in the Arctic has changed little in the nearly 87 years since Donald MacMillan sent Bowdoin the bear that stands guard in Morrell Gym, but some say the polar bear could actually become extinct in this century, a victim of global warming. Departments Mailbox 2 Bookshelf 4 College & Maine 6 Weddings 38 Class News 44 Obituaries 79 BOWDOINeditor’s note staff It’s winter in Maine, and January simply will not end. Money is short, patience is Volume 76, Number 2 thin, and the line at the coffeeshop is always long. Looking beyond Brunswick, Winter, 2005 one’s mood might plummet further – those who have friends and loved ones in MAGAZINE STAFF Iraq must know little but worry, and the figures of death and destruction from December’s tsunami loom as large as the wave itself.