The Educational Radio Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Mmmmmmm I I Mmmmmmmmm I M I M I

PUBLIC DISCLOSURE COPY Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ¸ Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Information about Form 990-PF and its separate instructions is at www.irs.gov/form990pf. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2014 or tax year beginning , 2014, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE WILLIAM & FLORA HEWLETT FOUNDATION 94-1655673 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) (650) 234 -4500 2121 SAND HILL ROAD City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code m m m m m m m C If exemption application is I pending, check here MENLO PARK, CA 94025 G m m I Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm here m mand m attach m m m m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization:X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminatedm I Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I J X Fair market value of all assets at Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminationm I end of year (from Part II, col. -

Bilaga C Exempel På Abuseärenden

Bilaga C Exempel på abuseärenden Notera att information om avsändare och annan personlig information är borttagen ur dessa exempel. Exempel 1 – Copyright Compliance Notice ID: 22-102071976 Notice Date: 28 Aug 2013 03:56:47 GMT Foreningen For Digitala Fri- Och Rattigheter Dear Sir or Madam: Irdeto USA, Inc. (hereinafter referred to as "Irdeto") swears under penalty of perjury that Paramount Pictures Corporation ("Paramount") has authorized Irdeto to act as its non-exclusive agent for copyright infringement notification. Irdeto's search of the protocol listed below has detected infringements of Paramount's copyright interests on your IP addresses as detailed in the below report. Irdeto has reasonable good faith belief that use of the material in the manner complained of in the below report is not authorized by Paramount, its agents, or the law. The information provided herein is accurate to the best of our knowledge. Therefore, this letter is an official notification to effect removal of the detected infringement listed in the below report. The Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, the Universal Copyright Convention, as well as bilateral treaties with other countries allow for protection of client's copyrighted work even beyond U.S. borders. The below documentation specifies the exact location of the infringement. We hereby request that you immediately remove or block access to the infringing material, as specified in the copyright laws, and insure the user refrains from using or sharing with others unauthorized Paramount's materials in the future. Further, we believe that the entire Internet community benefits when these matters are resolved cooperatively. -

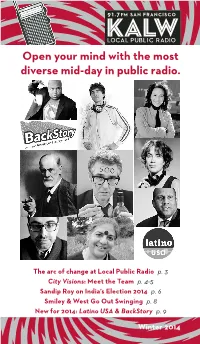

Open Your Mind with the Most Diverse Mid-Day in Public Radio

Open your mind with the most diverse mid-day in public radio. The arc of change at Local Public Radio p. 3 City Visions: Meet the Team p. 4-5 Sandip Roy on India’s Election 2014 p. 6 Smiley & West Go Out Swinging p. 8 New for 2014: Latino USA & BackStory p. 9 Winter 2014 KALW: By and for the community . COMMUNITY BROADCAST PARTNERS AIA, San Francisco • Association for Continuing Education • Berkeley Symphony Orchestra • Burton High School • East Bay Express • Global Exchange • INFORUM at The Commonwealth Club • Jewish Community Center of San Francisco • LitQuake • Mills College • New America Media • Oakland Asian Cultural Center • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UC Berkeley • Other Minds • outLoud Radio Radio Ambulante • San Francisco Arts Commission • San Francisco Conservatory of Music • San Quentin Prison Radio • SF Performances • Stanford Storytelling Project • StoryCorps • Youth Radio KALW VOLUNTEER PRODUCERS Rachel Altman, Wendy Baker, Sarag Bernard, Susie Britton, Sarah Cahill, Tiffany Camhi, Bob Campbell, Lisa Carmack, Lisa Denenmark, Maya de Paula Hanika, Julie Dewitt, Matt Fidler, Chuck Finney, Richard Friedman, Ninna Gaensler-Debs, Mary Goode Willis, Anne Huang, Eric Jansen, Linda Jue, Alyssa Kapnik, Carol Kocivar, Ashleyanne Krigbaum, David Latulippe, Teddy Lederer, JoAnn Mar, Martin MacClain, Daphne Matziaraki, Holly McDede, Lauren Meltzer, Charlie Mintz, Sandy Miranda, Emmanuel Nado, Marty Nemko, Erik Neumann, Edwin Okong’o, Kevin Oliver, David Onek, Joseph Pace, Liz Pfeffer, Marilyn Pittman, Mary Rees, Dana Rodriguez, -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

The Prepared Community Phase II Targeted Outreach Network

The Prepared Community Phase II Targeted Outreach Network County Bernalillo County Prepared By Bernalillo County Community Health Council Date Completed July 2006 Contact Person Leigh Mason Title Coordinator Email Address [email protected] Communications Channels in Bernalillo County The radio stations that residents of Bernalillo County listen to with contact information are in Table 1. KLYT FM 88.3 Christian Contemporary 505-338-3688 KANW FM 89.1 Public Radio 505-242-7163 KUNM FM 89.9 Public Radio 505-277-4806 KFLQ FM 91.5 Religious 505-296-9100 KRST FM 92.3 Religious 505-767-6700 KKOB FM 93.3 Top-40 505-767-6700 KZRR FM 94.1 Rock 505-830-6400 KBZU FM 96.3 Classic Rock 505-767-6700 KMGA FM 99.5 Adult Contemporary 505-767-6700 KPEK FM 100.3 Modern Adult Contemporary 505-299-7325 KJFA FM 101.3 Spanish 505-262-1142 KDRF FM 103.3 Adult Contemporary 505-767-6700 KBQI FM 107.9 Country 505-830-6400 KNML AM 610 Sports 505-767-6700 KDAZ AM 730 Spanish 505-345-7373 KKOB AM 770 News/Talk 505-767-6700 KSVA AM 920 Religious 505-890-0800 KKIM AM 1000 Religious 505-341-9400 KDEF AM 1150 News 505-888-1150 KABQ AM 1350 Talk 505-830-6400 KRZY AM 1450 Spanish 505-342-4141 KKJY AM 1550 Nostalgia 505-899-5029 KRKE AM 1600 News/Talk 505-899-5029 Newspapers Albuquerque Journal 505-823-3393 Distributed Daily Albuquerque Tribune 505-823-7777 Distributed Daily UNM Daily Lobo 505-277-5656 Distributed Daily Weekly Alibi 505-346-0660 Distributed Weekly Crosswinds Weekly 505-883-4750 Distributed Weekly Albuquerque Television Stations KOAT ABC Channel 7 (505) 884-7777 KASA FOX Channel 2 (505) 246-2222 KRQE CBS Channel 13 (505) 243-2285 KAZQ Independent Channel 32 (505) 884-8355 KOBTV NBC Channel 4 (505) 243-4411 KNME PBS Channel 5 (505) 277-2922 KTFQ Telefutura Channel 14 (505) 262-1142 KASY UPN Channel 50 (505) 797-1919 KWBQ WB Channel 19 (505) 797-1919 Reverse 9-1-1 Bernalillo County is equipped with Reverse 911 capabilities. -

Public Notice >> Licensing and Management System Admin >>

REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122670 Renewal of FM KLWL 176981 Main 88.1 CHILLICOTHE, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000123755 Renewal of FM KCOU 28513 Main 88.1 COLUMBIA, MO The Curators of the 01/21/2021 Granted License University of Missouri From: To: 0000123699 Renewal of FL KSOZ-LP 192818 96.5 SALEM, MO Salem Christian 01/21/2021 Granted License Catholic Radio From: To: 0000123441 Renewal of FM KLOU 9626 Main 103.3 ST. LOUIS, MO CITICASTERS 01/21/2021 Granted License LICENSES, INC. From: To: 0000121465 Renewal of FX K244FQ 201060 96.7 ELKADER, IA DESIGN HOMES, INC. 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122687 Renewal of FM KNLP 83446 Main 89.7 POTOSI, MO NEW LIFE 01/21/2021 Granted License EVANGELISTIC CENTER, INC From: To: Page 1 of 146 REPORT NO. PN-2-210125-01 | PUBLISH DATE: 01/25/2021 Federal Communications Commission 45 L Street NE PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media info. (202) 418-0500 ACTIONS File Number Purpose Service Call Sign Facility ID Station Type Channel/Freq. City, State Applicant or Licensee Status Date Status 0000122266 Renewal of FX K217GC 92311 Main 91.3 NEVADA, MO CSN INTERNATIONAL 01/21/2021 Granted License From: To: 0000122046 Renewal of FM KRXL 34973 Main 94.5 KIRKSVILLE, MO KIRX, INC. -

Listening Patterns – 2 About the Study Creating the Format Groups

SSRRGG PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo PPrrooffiillee TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss AA SSiixx--YYeeaarr AAnnaallyyssiiss ooff PPeerrffoorrmmaannccee aanndd CChhaannggee BByy SSttaattiioonn FFoorrmmaatt By Thomas J. Thomas and Theresa R. Clifford December 2005 STATION RESOURCE GROUP 6935 Laurel Avenue Takoma Park, MD 20912 301.270.2617 www.srg.org TThhee PPuubblliicc RRaaddiioo FFoorrmmaatt SSttuuddyy:: LLiisstteenniinngg PPaatttteerrnnss Each week the 393 public radio organizations supported by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting reach some 27 million listeners. Most analyses of public radio listening examine the performance of individual stations within this large mix, the contributions of specific national programs, or aggregate numbers for the system as a whole. This report takes a different approach. Through an extensive, multi-year study of 228 stations that generate about 80% of public radio’s audience, we review patterns of listening to groups of stations categorized by the formats that they present. We find that stations that pursue different format strategies – news, classical, jazz, AAA, and the principal combinations of these – have experienced significantly different patterns of audience growth in recent years and important differences in key audience behaviors such as loyalty and time spent listening. This quantitative study complements qualitative research that the Station Resource Group, in partnership with Public Radio Program Directors, and others have pursued on the values and benefits listeners perceive in different formats and format combinations. Key findings of The Public Radio Format Study include: • In a time of relentless news cycles and a near abandonment of news by many commercial stations, public radio’s news and information stations have seen a 55% increase in their average audience from Spring 1999 to Fall 2004. -

Ii~I~~111\11 3 0307 00072 6078

II \If'\\II\I\\OOI~~\~~~II~I~~111\11 3 0307 00072 6078 This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Senate Rule 71. Provision shall be made for news reporters on the Senate floor in limited numbers, and in the Senate gallery. Because of limited space on the floor, permanent space is I limited to those news agencies which have regularly covered the legislature, namely: The Associated Press, St. Paul Pioneer Press, Star Tribune, Duluth News-Tribune, Fargo Forum, Publication of: Rochester Post-Bulletin, St. Cloud Daily Times, WCCO radio, KSTP radio and Minnesota Public Radio. -An additional two The Minnesota Senate spaces shall be provided to other reporters if space is available. Office of the Secretary of the Senate ~ -:- Patrick E. flahaven One person Jrom each named agency and one person from the 231 State Capitol Senate Publications Office may be present at tbe press table on St. Paul, Minnesota 55155 the Senate floor at anyone time. (651) 296-2344 Other news media personnel may occupy seats provided in the Accredited through: Senate gallery. Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Sven lindquist The Committee on Rules and Administration may, through Room 1, State Capitol committee action or by delegating authority to the Secretary, St. Paul, Minnesota 55155 allow television filming on the Senate floor on certain occasions. (651) 296-1119 The Secretary of the Senate shall compile and distribute to the This publication was developed by the staff of public a directory of reporters accredited to report from the Senate Media Services and Senate Sergeant's Office Senate floor. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST. -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

Teacher Feature: Teresa Haider

Famil y Education y Childhood Earl MoorheadCommunityEducation 2410 14th Street South ◆ Moorhead, MN 56560 ◆ 284-3400 Vol. 11, Issue 2 ◆ Winter 2011 Teacher Feature: Teresa Haider Teresa Haider has Q: Do you have a favorite age group or topic Q: What is your favorite family activity? been teaching for you like to teach? A: Summer at the lakes, boating and Early Childhood A: It is so much fun to get to know the cooking family meals together. Family Education preschoolers and their families who are and School with me all year. Those four and five-year- Q: What word or phrase best describes your Readiness for more olds are always looking out for me! I check family of origin? than 18 years. every day to see if they bring their smiles A: A large extended family of cousins, During this time she to school. One day a little boy brought me aunts, uncles, but mostly cousins. has watched one to keep (two eyes and a smile were families send their drawn on a small green slip of paper). I Q: If you could give parents one bit of advice oldest children to her for preschool then keep it in my jewelry box! to follow, what would it be? another child and another. We hope she stays A: Talk with your children and listen to to see the next generation off to such a good Another student looked at me on the last what they say — even before they can talk. early start! Here are some things you may or day of preschool and said, “…teacher, Enjoy humor and laughter with them too. -

Gramma& Contact and Time

GRAMMA& CONTACT AND TIME Marianne Mithun University of California, Santa Bar.bara l. Thc "drea: Callforrria North America is home to oonsiderable linguistio diversity, with 55-60 distinot language families and isolates in the traditional sense, that is, the largest genetic groups that can be established by the oomparative met&od. Of these, 22 are represented in California. Some Califomia languages are members of large families that extsnd ov€r wide areas of the continent, such as Uto-Azteoan, Algic (Athabaskan-Wiyot-Yurok), and Athabaskan-Eyak-T1ingit. Others belong to medium or snall families spoken mainly or wholly within California such as Utian (12 languages),Yuman (11), Pomoan (7), Chumashan(6), Shastan(4), Maidun (4), Wintun (4), Yokutsan (3), Palaihnihan (2), and Yuki-Wappo (2). Some are isolates: Karuh Chimariko, Yan4 Washo, Esselen, and Salinan. Most of the ourrently aooepted genetio classfioation was establishedover a century ago @owell 1891). Looations of the languagoscan be seenin Figure t. In 1903, Dixon and Kroeber noted skuctural resemblanoes among some ofthese families and isolates arld ascribsd them simply to oommon t'?ology. Tor years later, they hypothesized that the similarities might be due to distant gcnetio relatiorxhip and proposed" primarily on the basis of grammatioal skuoture" two possible 'stoclc' or groups of families, whioh they named Hokan and Penutian. The original Hokan hypotheis linted Karulq Chinariko, Yana, Shastaa, Palaihnihan, Pomoan, Esselen, and Yuman. Over the next half-oenhrry, various scholars added the Washo, Salinan, and Chumashan families from Califomia; the Tonkawa, Karankaw4 and Coahuilteoo languages from Texas; Seri, Tequistlatecan, and Tlappanec &om Mexioo; Subtiaba from Nioaragua; and Jioaque from Honduras- Some of the proposals remain promising, and others havo sinoe been abandoned.