Williamstown and Williams College: Explorations in Local History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ocm35117078-1897.Pdf (6.776Mb)

t~\ yy -•r'. ,-rv :K ft. U JU ■S y T y f Tr>, ^ - T - t v - |i •; -4- X ' ■'■ X ' ;'H; ': :? \ A is - K 1 i - > \X . ,—iLr ml ~-m V«^ 4 — m*- - ■■.- X X — xy /*v /-s s r y t * y y y .C' ^ y yr yy y ^ H' p N w -J^L Ji.iL Jl ,-x O ’ a O x y y f<i$ ^4 >y I PUBLIC DOCUMENT . N o. 50. dUmmionforalllj of PassacJjtmtts. Report or the Commissioners O N T H E Topographical Survey. F oe t h e Y e a r 1 8 9 7 . BOSTON: WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS, 18 Post Office Squake. 1898. REPORT. Boston, Dec. 31, 1897. To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives, Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The Commissioners on the Topographical Sur vey and Map of the State present the following report of the work executed under their direction during the year 1897. The determination of the town boundary lines has been carried on under the same general plan as in preceding years. The supervision and oversight of the work from 1895 to 1897 Avere undertaken as a labor of love by the chairman of the Board, the late Prof. Henry L. Whiting. It Avas found, OAving to other engagements and advancing years, that he was unable to devote as much time to the survey as the work required, and the last Legislature in creased the appropriation for carrying on the work of the Board, in order that a chief engineer might be employed, who should relieve the chairman of some of his responsible duties. -

Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Dedicated to the Preservation, Protection and Enjoyment of the Forest Preserve

The Lookout April - May 2020 Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Dedicated to the preservation, protection and enjoyment of the Forest Preserve http://www.adk-schenectady.org Adirondack Mountain Club — Schenectady Chapter Board ELECTED OFFICERS CHAIR: LOOKOUT EDITOR: Dustin Wright Mal Provost 603-953-8782 518-399-1565 [email protected] [email protected] VICE-CHAIR: MEMBERSHIP: Stan Stoklosa Jeff Newsome 518-383-3066 [email protected] [email protected] NORTHVILLE PLACID TRAIL: SECRETARY: Mary MacDonald Heather Ipsen 518-371-1293 [email protected] [email protected] TREASURER: OUTINGS: Colin Thomas Roy Keats [email protected] 518-370-0399 [email protected] DIRECTOR: Jason Waters PRINTING/MAILING: [email protected] Mary MacDonald 518-371-1293 PROJECT COORDINATORS: [email protected] Jacque McGinn 518-438-0557 PUBLICITY: [email protected] Mary Zawacki 914-373-8733 Sally Dewes [email protected] 518-346-1761 [email protected] TRAILS: Norm Kuchar VACANT 518-399-6243 [email protected] [email protected] APPOINTED MEMBERS WEB MASTER: Mary Zawacki CONSERVATION: 914-373-8733 Mal Provost [email protected] 518-399-1565 [email protected] WHITEWATER: Ralph Pascale PROGRAMS: 518-235-1614 [email protected] Sally Dewes 518-346-1761 [email protected] YOUNG MEMBERS GROUP: Dustin Wright 603-953-8782 [email protected] There is a lot of history in a canoe paddle that Norm Kuchar presented to Neil On the cover Woodworth at the recent Conservation Committee meeting. See Page 3. Photo by Sally Dewes Inside this issue: April - May 2020 Pandemic Interruptions 2 Woodworth Honored 3 Whitewater Season 4-5 Outings 6-7 The Lookout Ididaride 8 Trip Tales 10-12 The Newsletter for the Schenectady Chapter of the Adirondack Mountain Club Advocates Press Legislators On Rangers Budget Along the crowded hallways of the Legislative Office Building and Capitol Feb. -

Rensselaer Land Trust

Rensselaer Land Trust Land Conservation Plan: 2018 to 2030 June 2018 Prepared by: John Winter and Jim Tolisano, Innovations in Conservation, LLC Rick Barnes Michael Batcher Nick Conrad The preparation of this Land Conservation Plan has been made possible by grants and contributions from: • New York State Environmental Protection Fund through: o The NYS Conservation Partnership Program led by the Land Trust Alliance and the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC), and o The Hudson River Estuary Program of NYSDEC, • The Hudson River Valley Greenway, • Royal Bank of Canada, • The Louis and Hortense Rubin Foundation, and • Volunteers from the Rensselaer Land Trust who provided in-kind matching support. Rensselaer Land Trust Conservation Plan DRAFT 6-1-18 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary Page 6 1. Introduction 8 Purpose of the Land Conservation Plan 8 The Case for Land Conservation Planning 9 2. Preparing the Plan 10 3. Community Inputs 13 4. Existing Conditions 17 Water Resources 17 Ecological Resources 25 Responding to Changes in Climate (Climate Resiliency) 31 Agricultural Resources 33 Scenic Resources 36 5. Conservation Priority Areas 38 Water Resource Priorities 38 Ecological Resource Priorities 42 Climate Resiliency for Biodiversity Resource Priorities 46 Agricultural Resource Priorities 51 Scenic Resource Priorities 55 Composite Resource Priorities 59 Maximum Score for Priority Areas 62 6. Land Conservation Tools 64 7. Conservation Partners 68 Rensselaer Land Trust Conservation Plan DRAFT 6-1-18 3 8. Work Plan 75 9. Acknowledgements 76 10. References 78 Appendices 80 Appendix A - Community Selected Conservation Areas by Municipality 80 Appendix B - Priority Scoring Methodology 85 Appendix C - Ecological Feature Descriptions Used for Analysis 91 Appendix D: A Brief History of Rensselaer County 100 Appendix E: Rensselaer County and Its Regional and Local Setting 102 Appendices F through U: Municipality Conservation Priorities 104 Figures 1. -

ADK July-Sept

JULY-SEPTEMBER 2006 No. 0604 chepontuc — “Hard place to cross”, Iroquois reference to Glens Falls hepontuc ootnotes C THE NEWSLETTER OF THE GLENS FALLS-SARATOGAF CHAPTER OF THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB Annual Dinner set for Oct. 20 ark your calendars! Please join your fellow ADKers Gathering will feature Carl Heilman on Friday, October 20, for M our annual Chapter Dinner. presenting his award-winning Weʼre moving to larger surroundings — the Queensbury Hotel in Glens Falls — to multimedia slide show, “Wild Visions” make room for everybody who wants to attend. Once again we have a fabulous program: home. He has worked in the region as an Adirondack Heritage award from the We are honored to welcome the Obi Wan a carpenter and contractor, and over the Association for the Protection of the of Adirondack Photography: Carl Heilman years also became well-known for his Adirondacks for his work with photog- who will present his award-winning mul- traditionally hand-crafted snowshoes and raphy. timedia slide Adirondack presentation his snowshoeing expertise. Each winter, as a NYS licensed guide, “Wild Visions.” Itʼs an honor to welcome Carl has been photographing the wil- he leads backcountry snowshoeing work- Carl as heʼs been busy the last few years derness landscape since 1975, working shops for the Adirondack Mountain Club publishing books, teaching master work- to capture on film both the grandeur of at the Adirondak Loj near Lake Placid, shops in photography and producing won- these special places, and the emotional and for the Appalachian Mountain Club derful photography. and spiritual connection he has felt as at Pinkham Notch, N.H. -

Deep-Green Economy

A L U MNI REVIEW September 2009 100 DEEP-GREEN ECONOMY 1 | WILLIAMS ALUMNI REVIE W | SP R ING 2005 24 7 12 3 ALUMNI REVIEW Volume No. 104, Issue No. 2 Editor Student Assistant Amy T. Lovett Amanda Korman ’10 Assistant Editor Design & Production departments Jennifer E. Grow Jane Firor & Associates LLC Editorial Offices P.O. Box 676, Williamstown, MA 01267-0676, tel: 413.597.4278, Opinions & Expressions fax: 413.597.4158, e-mail: [email protected], web: http://alumni.williams. edu/alumnireview Interim President Bill Wagner Address Changes/Updates Bio Records, 75 Park St., Williamstown, MA 01267-2114, introduces himself. … Young tel: 413.597.4399, fax: 413.458.9808, e-mail: [email protected], web: http://alumni.williams.edu/updatemyprofile alums help Iraqi refugee girls Williams magazine (USPS No. 684-580) is published in August, September, December, reclaim their childhoods. … January, March, April and June and distributed free of charge by Williams College for the Society of Alumni. Opinions expressed in this publication may not necessarily reflect those Letters from readers. 2 of Williams College or of the Society of Alumni. Periodical postage paid at Williamstown, MA 01267 and additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to Williams magazine, 75 Park St., Williamstown, Scene & Herd MA 01267-2114 News of Williams and beyond. 4 WILLIAMS COLLEGE Board of Trustees Bill Wagner, Interim President • Gregory M. Avis ’80, Chairman of the Life of the Mind Board • Keli Kaegi, Secretary to the Board Psych Prof. Laurie Heatherington César J. Alvarez ’84 • Barbara A. Austell ’75 • David C. Bowen ’83 • Valda Clark Christian ’92 • E. -

Spring Catalog 20082008 OLLI • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE Formerly Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL)

PARTNERS IN EDUCATION WITH WILLIAMS COLLEGE BARD COLLEGE AT SIMON’S ROCK MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS AT BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE www.BerkshireOLLI.org • 413.236.2190 Spring Catalog 20082008 OLLI • Osher Lifelong Learning Institute AT BERKSHIRE COMMUNITY COLLEGE Formerly Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL) WELCOME TO OLLI AT BCC The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute (OLLI) at Berkshire Community College was established in 2007 following a grant from the Bernard Osher Foundation of San Francisco to the Berkshire Institute for Lifetime Learning (BILL). Founded in 1994 as a volunteer-run organization, BILL fostered lifelong learning opportunities for adults in the culture-rich Berkshire area. Building on this tradition, OLLI continues the classes, trips, special events and lectures that members value. As part of the nationwide OLLI network, members can enjoy educational resources, ideas and advanced technologies that offer an even wider range of learning. In addition to Berkshire Community College, OLLI is a partner in education with Williams College, Bard College at Simon’s Rock and Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts and has cultural partners including the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute. These institutions give generously of their faculty and facilities to enrich the lifetime learning of OLLI members. N Choose from among 50-plus (noncredit) courses in a variety of subject areas offered in the fall, winter, spring and summer semesters. N Attend distinguished speaker lectures and panel discussions that stimulate and inform. N Experience history and culture through special events and trips. N Network with other members to form groups of mutual interest. LEARN – EXPLORE – ENJOY JOIN OLLI UPCOMING EVENTS AND LECTURES March . -

November/December 2007

www.nynjtc.org Connecting People with Nature since 1920 November/December 2007 New York-New Jersey Trail Conference — Maintaining 1,700 Miles of Foot Trails In this issue: Crowd Builds RPH Bridge...pg 3 • A Library for Hikers....pg 6 • Are Those Pines Sick, Or What?...pg 7 • Avoid Hunters, Hike Local...pg 12 revamped. There was an enormous amount BELLEAYRE Trail Blazes of Glory of out-blazing the old markers, putting up new markers, closing trails, clearing the By Brenda Freeman-Bates, Senior Curator, Ward Pound Ridge Reservation trails of over-hanging and fallen debris, Agreement Scales reconfiguring trails, walking them in the different seasons, tweaking the blazes, and Back Resort and having a good time while doing it all. A new trail map has also been printed, Protects Over with great thanks and gratitude to the Trail Conference for sharing its GPS database of the trails with the Westchester County 1,400 Acres of Department of Planning. The new color map and brochure now correctly reflect Land in New York N O the trail system, with points of interest, I T A V topographical lines, forests, fields, and On September 5, 2007, Governor Spitzer R E S E wetlands indicated. announced an agreement regarding the R E G This amazing feat would never have been Belleayre Resort at Catskill Park develop - D I R accomplished so expeditiously without the ment proposal after a seven-year legal and D N U dedication of volunteers. To date, a very regulatory battle over the project. The O P D impressive 928.5 volunteer hours have agreement between the project sponsor, R A W : been recorded for this project. -

Geographic Names

GEOGRAPHIC NAMES CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES ? REVISED TO JANUARY, 1911 WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1911 PREPARED FOR USE IN THE GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE BY THE UNITED STATES GEOGRAPHIC BOARD WASHINGTON, D. C, JANUARY, 1911 ) CORRECT ORTHOGRAPHY OF GEOGRAPHIC NAMES. The following list of geographic names includes all decisions on spelling rendered by the United States Geographic Board to and including December 7, 1910. Adopted forms are shown by bold-face type, rejected forms by italic, and revisions of previous decisions by an asterisk (*). Aalplaus ; see Alplaus. Acoma; township, McLeod County, Minn. Abagadasset; point, Kennebec River, Saga- (Not Aconia.) dahoc County, Me. (Not Abagadusset. AQores ; see Azores. Abatan; river, southwest part of Bohol, Acquasco; see Aquaseo. discharging into Maribojoc Bay. (Not Acquia; see Aquia. Abalan nor Abalon.) Acworth; railroad station and town, Cobb Aberjona; river, IVIiddlesex County, Mass. County, Ga. (Not Ackworth.) (Not Abbajona.) Adam; island, Chesapeake Bay, Dorchester Abino; point, in Canada, near east end of County, Md. (Not Adam's nor Adams.) Lake Erie. (Not Abineau nor Albino.) Adams; creek, Chatham County, Ga. (Not Aboite; railroad station, Allen County, Adams's.) Ind. (Not Aboit.) Adams; township. Warren County, Ind. AJjoo-shehr ; see Bushire. (Not J. Q. Adams.) Abookeer; AhouJcir; see Abukir. Adam's Creek; see Cunningham. Ahou Hamad; see Abu Hamed. Adams Fall; ledge in New Haven Harbor, Fall.) Abram ; creek in Grant and Mineral Coun- Conn. (Not Adam's ties, W. Va. (Not Abraham.) Adel; see Somali. Abram; see Shimmo. Adelina; town, Calvert County, Md. (Not Abruad ; see Riad. Adalina.) Absaroka; range of mountains in and near Aderhold; ferry over Chattahoochee River, Yellowstone National Park. -

Town of Williamstown, Massachusetts 2019 Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT -2019- TOWN OF WILLIAMSTOWN, MASSACHUSETTS 2019 ANNUAL REPORT Department reports are for the calendar year 2019 unless otherwise noted Financial report covers the fiscal year ending June 30, 2019 Prepared by Sarah Hurlbut, Debra Turnbull Published by Beck’s Printing Company. 2020 www.williamstownma.gov 1 2019 ANNUAL REPORT: CONTENTS COVER STORY 3 CURRENT TOWN OFFICIALS 5 SELECT BOARD 10 TOWN MANAGER 11 1753 HOUSE COMMITTEE 13 ACCOUNTANT 14 AFFORDABLE HOUSING TRUST FUND 21 AGRICULTURAL COMMISSION 22 BOARD OF ASSESSORS 23 COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT 25 BUILDING OFFICIALS 25 PLANNING AND LAND USE 27 HEALTH DEPT. 28 SEALER OF WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 31 COMMUNITY PRESERVATION ACT COMMITTEE 32 CONSERVATION COMMISSION 33 COUNCIL ON AGING 34 DAVID & JOYCE MILNE PUBLIC LIBRARY 37 FINANCE COMMITTEE 41 DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC WORKS 42 HISTORICAL COMMISSION 44 HOOSAC WATER QUALITY DISTRICT 45 MOUNT GREYLOCK REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICT 46 NORTHERN BERKSHIRE CULTURAL COUNCIL 52 NORTHERN BERKSHIRE VOCATIONAL REGIONAL SCHOOL DISTRICT 53 NORTHERN BERKSHIRE SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT DISTRICT 58 PLANNING BOARD 59 WILLIAMSTOWN POLICE DEPARTMENT 60 FOREST WARDEN 71 SIGN COMMISSION 76 TOWN CLERK/BOARD OF REGISTRARS 77 TREASURER / COLLECTOR 92 VETERANS SERVICES 97 WATER AND SEWER 98 WILLIAMSTOWN ELEMENTARY 99 WILLIAMSTOWN HOUSING AUTHORITY 101 WILLIAMSTOWN MUNICIPAL SCHOLARSHIP FUND 101 ZONING BOARD OF APPEALS 102 APPENDICES 103 WILLIAMSTOWN HISTORICAL MUSEUM 104 WILLIAMSTOWN YOUTH CENTER 107 WILLIAMSTOWN FIRE DISTRICT 109 2 COVER STORY The End of an Era This year we would like to reflect on the careers of three retiring department heads. Mary Kennedy, Town Clerk, Janet Saddler, Treasurer Collector and Finance Director, and Tim Kaiser, Director of Public Works. -

FEATHERS Published by the Schenectcujy Bird Club

FEATHERS Published by the SchenectcuJy Bird Club Vol. 4. No. 1 January. 1942 FLICKERS AND BLUEBIRDS ARE FEATURED IN CHRISTMAS COUNT Chester N. Moore, Chairman, Christmas Count Committee Sohenectady, N.Y. (Mohawk River from Lock 8 to Mohawk View, Collins Lake, Woestlna Sanctuary and lower Rotterdam Hills, Central Park, Vale and Parkwood Cemeteries, Meadowdale, Indian Ladder, Puller and Oxford Road sections of Albany, Albany Air port, Consaul Road, Watervllet Reservoir, and Intervening ter ritory. ) — Dec. 21; 7 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Clear; wind moder ate, northwest; fields mostly covered with light, crusted snow; minimum of open water; temp. -4° at start, 13 at noon, 11° at return. Twenty-five observers working In eight par ties. Total party hours afield, 47; total party miles, 198 (40 afoot, 158 by 'ar, Incidental to trips afoot). Black Duck, 1; American Merganser, 6; Red-tailed Bawk, 2; Red- shouldered Hawk, 1; Rough-legged Bawk, 9; Marsh Hawk, 3; Spar row Hawk, 2; Ruffed Grouse, 9; Ring-necked Pheasant, 37; Her ring Gull, 4; Great Horned Owl, 2; Flicker, 2 (In distinctly separate localities, one by B. D. Miller, Moore and Stone, the other by Preese, Kelly and OleBon); Hairy Woodpecker, 15; Downy Woodpecker, 47; Blue Jay, 110; Crow, 1133; Black-capped Chickadee, 240; White-breasted Nuthatch, 42; Red-breasted Nut hatch, 1; Brown Creeper, 3; Bluebird, 2 (first found by call notes, then seen at close range by Havens and P. S. Miller); Golden-orowned Kinglet, 4; Northern Shrike, 2; Starling, 559; English Sparrow, 547; Meadowlark, 2; Redpoll, 188; Pine Sis kin, 6; Goldfinch, 94; Slate-colored Junco, 69; Tree Sparrow, 748; Song Sparrow, 15; Snow Bunting, 30. -

GEOLOGIC RADON POTENTIAL of EPA REGION 1 Connecticut Maine Massachusetts New Hampshire Rhode Island Vermont

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC RADON POTENTIAL OF EPA REGION 1 Connecticut Maine Massachusetts New Hampshire Rhode Island Vermont OPEN-FILE REPORT 93-292-A Prepared in Cooperation with the | U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 9'% 1993 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U. S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC RADON POTENTIAL OF EPA REGION 1 Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont R. Randall Schumann EDITOR OPEN-FILE REPORT 93-292-A Prepared in cooperation with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency 1993 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. CONTENTS SECTION____________________________________PAGE 1. The USGS/EPA State Radon Potential Assessments: An Introduction 1 Linda C.S. Gundersen, R. Randall Schumann, and Sharon W. White Appendix A: Geologic Time Scale 19 Appendix B: Glossary of Terms 20 Appendix C: EPA Regional Offices, State Radon Contacts, 26 and State Geological Surveys 2. EPA Region 1 Geologic Radon Potential Summary 36 Linda C.S. Gundersen, R. Randall Schumann, and Sandra L. Szarzi 3. Preliminary Geologic Radon Potential Assessment of Connecticut 47 Linda C.S. Gundersen andR. Randall Schumann 4. Preliminary Geologic Radon Potential Assessment of Maine 83 Linda C.S. Gundersen andR. Randall Schumann 5. Preliminary Geologic Radon Potential Assessment of Massachusetts 123 R. Randall Schumann and Linda C.S. Gundersen 6. Preliminary Geologic Radon Potential Assessment of New Hampshire 157 Linda C.S. Gundersen andR. Randall Schumann 7. Preliminary Geologic Radon Potential Assessment of Rhode Island 191 Linda C.S. -

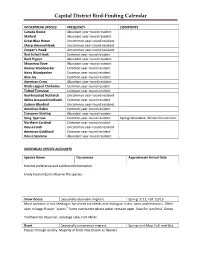

Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar

Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar WIDESPREAD SPECIES FREQUENCY COMMENTS Canada Goose Abundant year-round resident Mallard Abundant year-round resident Great Blue Heron Uncommon year-round resident Sharp-shinned Hawk Uncommon year-round resident Cooper’s Hawk Uncommon year-round resident Red-tailed Hawk Common year-round resident Rock Pigeon Abundant year-round resident Mourning Dove Abundant year-round resident Downy Woodpecker Common year-round resident Hairy Woodpecker Common year-round resident Blue Jay Common year-round resident American Crow Abundant year-round resident Black-capped Chickadee Common year-round resident Tufted Titmouse Common year-round resident Red-breasted Nuthatch Uncommon year-round resident White-breasted Nuthatch Common year-round resident Eastern Bluebird Uncommon year-round resident American Robin Common year-round resident European Starling Abundant year-round resident Song Sparrow Common year-round resident Spring=Abundant; Winter=Uncommon Northern Cardinal Common year-round resident House Finch Uncommon year-round resident American Goldfinch Common year-round resident House Sparrow Abundant year-round resident INDIVIDUAL SPECIES ACCOUNTS Species Name Occurrence Approximate Arrival Date Habitat preference and additional information. Likely location(s) to observe the species. Snow Goose Seasonally abundant migrant Spring: 3/12; Fall: 10/15 More common in fall, feeding in harvested cornfields and resting on rivers, lakes and reservoirs. Often seen in large, flyover “skeins.” Some overwinter where water remains open. Scan for rare Ross’ Goose. Tomhannock Reservoir, Saratoga Lake, Fort Miller. Brant Seasonally uncommon migrant Spring: mid-May; Fall: mid-Oct. Passes through quickly. Majority of birds heard/seen as flyovers. Capital District Bird-Finding Calendar Cackling Goose Seasonally uncommon migrant Spring and Fall Seen among migrating Canada Geese.