Averroes' Search

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Locke's Historical Method

RUCH FILOZOFICZNY LXXV 2019 4 Zbigniew Pietrzak University of Wrocław, Wrocław, Poland ORCID: 0000-0003-2458-1252 e-mail: [email protected] John Locke’s Historical Method and “Natural Histories” in Modern Natural Sciences DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12775/RF.2019.038 Introduction Among the many fundamental issues that helped shape the philosophy of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, one concerned the condi- tion of philosophy and scientific knowledge, and in the area of our inter- est – knowledge about nature.1 These philosophical inquiries included both subject-related problems concerning human cognitive abilities and object-related ones indicating possible epistemological boundaries that nature itself could have generated. Thus, already at the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, from Francis Bacon, Galileo, and 1 These reflections are an elaboration on the topic I mentioned in the article “His- toria naturalna a wiedza o naturze” [“Natural History vs. Knowledge of Nature”], in: Rozum, człowiek, historia, [Mind, Man, History], ed. Jakub Szczepański (Cracow: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 2018); as well as in my master’s thesis: The Crisis of Cognition, the Crisis of Philosophy (not published). It is also a debate over the content of Adam Grzeliński’s article entitled “‘Rozważania dotyczące rozu- mu ludzkiego’ Johna Locke’a: teoria poznania i historia” [“John Locke’s ‘An essay on human understanding’: cognition theory and history”], in: Rozum, człowiek, historia, ed. Jakub Szczepański, (Cracow: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 2018), as well as some of the themes of the author’s monograph Doświadczenie i rozum. Empiryzm Johna Locke’a [Experience and reason. The empiricism of John Locke] (To- ruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2019). -

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

Elisabeth Leinfellner.Indd

Drei Pioniere der philosophisch-linguistischen Analyse von Zeit und Tempus: Mauthner, Jespersen, Reichenbach Elisabeth Leinfellner, Wien [A philosophical school in Tlön] reasons that the present is indefi nite, that the future has no reality other than as a present hope, that the past has no reality other than as a present memory. Jorge Luis Borges, Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius 1. Einleitung: die semantische Rolle der Tempora Unsere alltägliche, ,psychologische‘, aber auch die abstrakte newtonsche oder mathematische Vorstellung von Zeit – die ,klassischen‘ Zeitvorstellungen – laufen darauf hinaus, dass es eine einfache lineare Abfolge von Vergangen- heit-Gegenwart-Zukunft gibt. Analysiert man jedoch natürliche Sprachen, dann bietet sich ein anderes, komplexeres Bild: Würde man der einfachen, klassischen Vorstellung folgen, dann käme man in der Sprache mit drei Tempora aus: Präsens, Präteritum, Futurum. Ein Blick in die Grammatiken verschiedener Sprachen zeigt aber, dass es auch andere Tempora neben die- sen dreien gibt, so im heutigen Deutsch das Plusquamperfekt und das Fu- turum exactum. Gewisse Tempora und auch temporale Ersatzformen lösen mehr oder minder glücklich das Problem, dass z.B. in einer Erzählung im Präteritum manchmal auch im zeitlichen Rückgriff eine Vergangenheit vor der Vergangenheit dargestellt werden muss, oder eine Zukunft in der Ver- gangenheit. Die Ursachen für eine nicht chronologische Darstellung sind vielfältig, z.B. stilistisch-textliche oder dass wir uns an Ereignisse nicht im- mer in der richtigen Reihenfolge erinnern. Weiters muss die Verwendung der Tempora in erzählenden Texten die Rekonstruktion des chronologischen Ablaufs von Ereignissen erlauben, z.B. aus praktischen Gründen. Dass Texte keineswegs immer chronologisch geordnet sind, hat in verschiedenen Disziplinen und oft im Gefolge des russischen Formalismus zu einer Unterscheidung zwischen zwei zeitlichen Achsen geführt, der chronologischen Achse der Abfolge der Ereignisse, und F. -

A History of Women Philosophers Vol. IV

A HISTORY OF WOMEN PHILOSOPHERS A History of Women Philosophers 1. Ancient Women Philosophers, 600 B.C.-500 A.D. 2. Medieval, Renaissance and Enlightenment Women Philosophers, 500-1600 3. Modern Women Philosophers, 1600-1900 4. Contemporary Women Philosophers, 1900-today PROFESSOR C. J. DE VOGEL A History of Women Philosophers Volume 4 Contemporary Women Philosophers 1900-today Edited by MARY ELLEN WAITHE Cleveland State University, Cleveland, U.S.A. Springer-Science+Business Media, B. V. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Contemporary women philosophers : 1900-today / edited by Mary Ellen Waithe. p. cm. -- (A History of women philosophers ; v. 4.) Includes bibliographical references (p. xxx-xxx) and index. ISBN 978-0-7923-2808-7 ISBN 978-94-011-1114-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-011-1114-0 1. Women philosophers. 2. Philosophy. Modern--20th century. r. Waithe. Mary Ellen. II. Series. Bl05.W6C66 1994 190' .82--dc20 94-9712 ISBN 978-0-7923-2808-7 printed an acid-free paper AII Rights Reserved © 1995 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Originally published by Kluwer Academic Publishers in 1995 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover lst edition 1995 No part of the material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the copyright owner. Contents Acknowledgements xv Introduction to Volume 4, by Mary Ellen Waithe xix 1. Victoria, Lady Welby (1837-1912), by William Andrew 1 Myers I. Introduction 1 II. Biography 1 III. -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

Mill's Conversion: the Herschel Connection

volume 18, no. 23 Introduction november 2018 John Stuart Mill’s A System of Logic, Ratiocinative and Inductive, being a connected view of the principles of evidence, and the methods of scientific investigation was the most popular and influential treatment of sci- entific method throughout the second half of the 19th century. As is well-known, there was a radical change in the view of probability en- dorsed between the first and second editions. There are three differ- Mill’s Conversion: ent conceptions of probability interacting throughout the history of probability: (1) Chance, or Propensity — for example, the bias of a bi- The Herschel Connection ased coin. (2) Judgmental Degree of Belief — for example, the de- gree of belief one should have that the bias is between .6 and .7 after 100 trials that produce 81 heads. (3) Long-Run Relative Frequency — for example, propor- tion of heads in a very large, or even infinite, number of flips of a given coin. It has been a matter of controversy, and continues to be to this day, which conceptions are basic. Strong advocates of one kind of prob- ability may deny that the others are important, or even that they make Brian Skyrms sense at all. University of California, Irvine, and Stanford University In the first edition of 1843, Mill espouses a frequency view of prob- ability that aligns well with his general material view of logic: Conclusions respecting the probability of a fact rest, not upon a different, but upon the very same basis, as conclu- sions respecting its certainly; namely, not our ignorance, © 2018 Brian Skyrms but our knowledge: knowledge obtained by experience, This work is licensed under a Creative Commons of the proportion between the cases in which the fact oc- Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. -

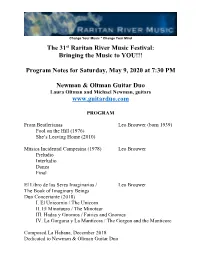

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society. -

WISDOM (Tlwma) and Pffllosophy (FALSAFA)

WISDOM (tLWMA) AND PfflLOSOPHY (FALSAFA) IN ISLAMIC THOUGHT (as a framework for inquiry) By: Mehmet ONAL This thcsis is submitted ror the Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Wales - Lampeter 1998 b"9tr In this study the following two hypothesisare researched: 1. "WisdotW' is the fundamental aspect of Islamic thought on which Islamic civilisation was established through Islamic law (,Sharfa), theology (Ldi-M), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Surism). 2. "Due to the first hypothesis Islamic philosophy is not only a commentary on the Greek philosophy or a new form of Ncoplatonism but a native Islamic wisdom understandingon the form of theoretical study". The present thesis consists of ten chaptersdealing with the concept of practical wisdom (Pikmq) and theoretical wisdom (philosophy or falsafa). At the end there arc a gcncral conclusion,glossary and bibliography. In the introduction (Chapter One) the definition of wisdom and philosophy is establishedas a conceptualground for the above two hypothesis. In the following chapter (Chapter Two) I focused on the historical background of these two concepts by giving a brief history of ancient wisdom and Greek philosophy as sourcesof Islamic thought. In the following two chapters (Chapter Three and Four) I tried to bring out a possibledefinition of Islamic wisdom in the Qur'5n and Sunna on which Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh), theology (A-alim), philosophy (falsafq) and mysticism (Sufism) consistedof. As a result of the above conceptual approaching,I tried to reach a new definition for wisdom (PiLma) as a method that helps in the establishmentof a new Islamic way of life and civilisation for our life. -

Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM

THAUMÀZEIN 8, 2020 Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM BETWEEN MYTHOLOGY AND EVO-DEVO Table of Contents: 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form; 2. The hundred eyes of Argos: Evo-Devo, evolutionary plasticity and historical constraints; 3. The wings of Pegasus: architectural constraints and mor- phospace; 4. Conclusions: from imaginary beings to fantastic beings. Perhaps universal history is the history of a few metaphors. J.L. Borges, Pascal’s Sphere, 1952. 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form «It is the animal with the big tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox’s brush. How I should like to get my hands on this tail sometime, but it is impossible, the animal is constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power of expression, whether they are concealed or bared» [Borges 1974, 17]. With these words Franz Kafka describes a bizarre creature that appeared in his dreams: a hybrid in which the perspicuous characters of morphologically and ethologically different animals – such as the fox and the kangaroo – are mixed to human somatic traits, recalling ancient mythological beings [Borghese 2009, 283]. Jorge Luis Borges accurately transcribes the words of the Prague writer in his Book of Imaginary Beings [Borges 1974], a manual of fan- tastic zoology written in collaboration with María Guerrero in 1957 and 39 Valeria Maggiore inscribed in the literary tradition of medieval bestiaries. -

Linguistic Scepticism in Mauthner's Philosophy

LiberaPisano Misunderstanding Metaphors: Linguistic ScepticisminMauthner’s Philosophy Nous sommes tous dans un désert. Personne ne comprend personne. Gustave Flaubert¹ This essayisanoverview of Fritz Mauthner’slinguistic scepticism, which, in my view, represents apowerful hermeneutic category of philosophical doubts about the com- municative,epistemological, and ontological value of language. In order to shed light on the main features of Mauthner’sthought, Idrawattention to his long-stand- ing dialogue with both the sceptical tradition and philosophyoflanguage. This con- tribution has nine short sections: the first has an introductory function and illus- tratesseveral aspectsoflinguistic scepticism in the history of philosophy; the second offers acontextualisation of Mauthner’sphilosophyoflanguage; the remain- der present abroad examination of the main features of Mauthner’sthought as fol- lows: the impossibility of knowledge that stems from aradicalisationofempiricism; the coincidencebetween wordand thought,thinkingand speaking;the notion of use, the relevanceoflinguistic habits,and the utopia of communication; the decep- tive metaphors at the root of an epoché of meaning;the new task of philosophyasan exercise of liberation against the limits of language; the controversial relationship between Judaism and scepticism; and the mystical silence as an extreme conse- quence of his thought.² Mauthnerturns scepticism into aform of life and philosophy into acritique of language, and he inauguratesanew approach that is traceable in manyGerman—Jewish -

The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves

1616796596 The Significant Other: a Literary History of Elves By Jenni Bergman Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff School of English, Communication and Philosophy Cardiff University 2011 UMI Number: U516593 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U516593 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted on candidature for any degree. Signed .(candidate) Date. STATEMENT 1 This thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD. (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 2 This thesis is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by explicit references. Signed. (candidate) Date. 3/A W/ STATEMENT 3 I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed (candidate) Date. STATEMENT 4 - BAR ON ACCESS APPROVED I hereby give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan after expiry of a bar on accessapproved bv the Graduate Development Committee. -

1 the Anglo-American Tradition of Liberty: a View From

The Anglo-American Tradition of Liberty: A View from Europe By João Carlos Espada (London and New York: Routledge Press, 2016). In the wake of Britain’s recent vote to leave the European Union, Professor Espada’s new book could not be more timely. For Espada argues persuasively that Europe benefits hugely from the example of British traditions of individual liberty and the rule of law. Although this book is a discussion of the ideas of a wide range of major theorists of political liberty, in his conclusion, Espada becomes an eloquent and passionate defender of Britain’s remaining in the European Union—for the sake of Europe more than for any benefit to Britain. Espada fears the centripetal forces of European bureaucracy in the absence of a British voice for individual liberty and local government. Espada had hoped that reforms within the EU might just entice Britain to stay. Perhaps eventually he will be proven right. As a study of modern liberal political theory, Espada’s new book is unusually personal. He recounts some of his own experiences in fascist Portugal and his lifelong love of things British, which led him to the study of political theory at Oxford University. While living in England, Espada was able to meet or study with several luminaries of twentieth-century liberal political theory, including Karl Popper, Ralf Dahrendorf, Isaiah Berlin, and Raymond Plant. Espada also mentions his experiences teaching in the United States, which led him to appreciate the thought of Alexis de Tocqueville and James Madison as well as Gertrude Himmelfarb and Irving Kristol.