Mannoury's Signific Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MATHEMATICS and the DIVINE: a HISTORICAL STUDY Edited by T

MATHEMATICS AND THE DIVINE: AHISTORICAL STUDY Cover illustration by Erich Lessing MATHEMATICS AND THE DIVINE: AHISTORICAL STUDY Edited by T. KOETSIER Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, The Netherlands L. BERGMANS Université de Paris IV – Sorbonne, Paris, France 2005 Amsterdam • Boston • Heidelberg • London • New York • Oxford • Paris • San Diego • San Francisco • Singapore • Sydney • Tokyo ELSEVIER B.V. ELSEVIER Inc. ELSEVIER Ltd ELSEVIER Ltd Sara Burgerhartstraat 25 525 B Street, Suite 1900 The Boulevard, Langford Lane 84 Theobalds Road P.O. Box 211, 1000 AE San Diego, CA 92101-4495 Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB London WC1X 8RR Amsterdam The Netherlands USA UK UK © 2005 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright by Elsevier B.V., and the following terms and conditions apply to its use: Photocopying Single photocopies of single chapters may be made for personal use as allowed by national copyright laws. Permission of the Publisher and payment of a fee is required for all other photocopying, including multiple or systematic copying, copying for advertising or promotional purposes, resale, and all forms of document delivery. Special rates are available for educational institutions that wish to make photocopies for non-profit educational classroom use. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone (+44) 1865 843830, fax (+44) 1865 853333, e-mail: [email protected]. Requests may also be completed on-line via the Elsevier homepage (http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissions). In the USA, users may clear permissions and make payments through the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, USA; phone: (+1) (978) 7508400, fax: (+1) (978) 7504744, and in the UK through the Copyright Licensing Agency Rapid Clearance Service (CLARCS), 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 0LP, UK; phone: (+44) 20 7631 5555; fax: (+44) 20 7631 5500. -

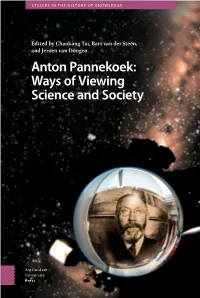

Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society

STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF KNOWLEDGE Tai, Van der Steen & Van Dongen (eds) Dongen & Van Steen der Van Tai, Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Ways of Viewing ScienceWays and Society Anton Pannekoek: Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Studies in the History of Knowledge This book series publishes leading volumes that study the history of knowledge in its cultural context. It aspires to offer accounts that cut across disciplinary and geographical boundaries, while being sensitive to how institutional circumstances and different scales of time shape the making of knowledge. Series Editors Klaas van Berkel, University of Groningen Jeroen van Dongen, University of Amsterdam Anton Pannekoek: Ways of Viewing Science and Society Edited by Chaokang Tai, Bart van der Steen, and Jeroen van Dongen Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: (Background) Fisheye lens photo of the Zeiss Planetarium Projector of Artis Amsterdam Royal Zoo in action. (Foreground) Fisheye lens photo of a portrait of Anton Pannekoek displayed in the common room of the Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy. Source: Jeronimo Voss Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 434 9 e-isbn 978 90 4853 500 2 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789462984349 nur 686 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2019 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Alternative Claims to the Discovery of Modern Logic: Coincidences and Diversification

Fran¸cois,K., L¨owe, B., Muller,¨ T., Van Kerkhove, B., editors, Foundations of the Formal Sciences VII Bringing together Philosophy and Sociology of Science Alternative claims to the discovery of modern logic: Coincidences and diversification Paul Ziche∗ Departement Wijsbegeerte, Universiteit Utrecht, Janskerkhof 13a, 3512 BL Utrecht, The Netherlands E-mail: [email protected] 1 Multiple and alternative discoveries No discipline could lay stronger claim to clarity and unequivocality than logic. Curiously, though, the historical genesis of modern logic presents a picture riven with rival claims over the discipline’s founding contributions. As will be shown, protagonists from highly different backgrounds assert that the genesis of modern logic—indeed, its very discovery—rests on their contribution. Not only are these claims, to some extent, mutually exclusive, they also cut across standards of scientificity and rationality. By standard narratives of the history of modern logic, some claimants to paternity seem downright obscure and anti-rational. Yet, all these claims are made within a narrow time-frame, and they all refer back to the same developments in mathematics. This makes it impossible to easily dismiss the rival claims. This paper argues that the co-existence of alternative claims concerning the discovery of modern logic, in fact, places the historian in an advanta- geous situation. It might appear as if the alternative claims make the the genesis of modern logic into a story of a multiple discovery, the coincidence of simultaneous discoveries of the same phenomenon. This is, however, not what the historical picture shows. The competing claims, very explicitly placed by the protagonists themselves, rather have to be viewed as stages within an open-ended process that would contribute not to an integrated picture of logic, but generate diversified conceptions of rationality. -

E.W. Beth Als Logicus

E.W. Beth als logicus ILLC Dissertation Series 2000-04 For further information about ILLC-publications, please contact Institute for Logic, Language and Computation Universiteit van Amsterdam Plantage Muidergracht 24 1018 TV Amsterdam phone: +31-20-525 6051 fax: +31-20-525 5206 e-mail: [email protected] homepage: http://www.illc.uva.nl/ E.W. Beth als logicus Verbeterde electronische versie (2001) van: Academisch Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magni¯cus prof.dr. J.J.M. Franse ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Aula der Universiteit op dinsdag 26 september 2000, te 10.00 uur door Paul van Ulsen geboren te Diemen Promotores: prof.dr. A.S. Troelstra prof.dr. J.F.A.K. van Benthem Faculteit Natuurwetenschappen, Wiskunde en Informatica Universiteit van Amsterdam Plantage Muidergracht 24 1018 TV Amsterdam Copyright c 2000 by P. van Ulsen Printed and bound by Print Partners Ipskamp. ISBN: 90{5776{052{5 Ter nagedachtenis aan mijn vader v Inhoudsopgave Dankwoord xi 1 Inleiding 1 2 Levensloop 11 2.1 Beginperiode . 12 2.1.1 Leerjaren . 12 2.1.2 Rijpingsproces . 14 2.2 Universitaire carriere . 21 2.2.1 Benoeming . 21 2.2.2 Geleerde genootschappen . 23 2.2.3 Redacteurschappen . 31 2.2.4 Beth naar Berkeley . 32 2.3 Beth op het hoogtepunt van zijn werk . 33 2.3.1 Instituut voor Grondslagenonderzoek . 33 2.3.2 Oprichting van de Centrale Interfaculteit . 37 2.3.3 Logici en historici aan Beths leiband . -

This Volume on the Vienna Circle's Influence in the Nordic Countries

Vol. 8, no. 1 (2013) Category: Review essay Written by Carlo Penco This volume on the Vienna Circle’s influence in the Nordic countries gives a very interesting presentation of an almost forgotten landmark. In the years preceding the Second World War, European philosophy was at the high point of its intellectual vitality. Everywhere philosophical societies promoted a dense network of connections among scholars, with international meetings and strong links among individuals and associations. In this context, the Vienna Circle emerges as one of the many, also if probably the most well-known, centres of diffusion of a new style of philosophy, closely linked to the new logic and with a strongly empiricist attitude. At the same time, empiricism, formal logic and psychology constituted (and still constitute) the common background of most of the Nordic philosophers, a background which permitted them to develop connections with Vienna’s cultural environment (well known also for the work of psychologists such as Sigmund Freud, but also Charlotte and Karl Bühler). This piece of history, although limited to the connection between Nordic philosophy and Vienna Circle, helps to clarify the history of European philosophy, and the sharp difference of Nordic philosophy in respect of the development of philosophy in Southern and Central Europe in the half a century following the Second World War. The editors say in the introduction: . one of the least known networks of the Vienna Circle is the “Nordic connection”. This connection had a continuing influence for many of the coming decades, beginning with the earliest phase of the Vienna Circle and continuing with a number of adaptations and innovations well into contemporary times. -

On His Students PM Van Hiele

Sketch of the influence by G. Mannoury (1867-1956) on his students P.M. van Hiele (1909-2010) and A.D. de Groot (1914- 2006), and the continued importance of this influence for a general theory of epistemology (2015), didactics of mathematics (2008) and methodology of science (including the humanities) (1990) Thomas Colignatus February 18 2016 http://thomascool.eu Draft Summary A discussion on epistemology and its role for mathematics and science is more fruitful when it is made more specific by focussing on didactics of mathematics and methodology of science (including the humanities). Both philosophy and mathematics run the risk of getting lost in abstraction, and it is better to have an anchor in the empirical science of the didactics of mathematics. The General Theory of Knowledge (GTOK) presented by Colignatus in 2015 has roots in the work of three figures in Holland 1926-1970, namely G. Mannoury (1867-1956) and his students P.M. van Hiele (1909-2010) and A.D. de Groot (1914-2006). The work by Van Hiele tends to be lesser known by philosophers, because Van Hiele tended to publish his work under the heading of didactics of mathematics. This article clarifies the link from Mannoury (didactics and significs / semiotics) to the epistemology and didactics with Van Hiele levels of insight (for any subject and not just mathematics). The other path from Mannoury via De Groot concerns methodology. Both paths join up into GTOK. This article has an implication for education in mathematics. The German immigrant Hans Freudenthal (1905-1990) was a stranger to Mannoury's approach, and developed "realistic mathematics education" (RME) based upon Jenaplan influences (by his wife) and a distortion and intellectual theft of Van Hiele's work (which distortion doesn't reduce the theft). -

Dutch Research School of Philosophy OZSW 2013 Conference

Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam Dutch Research School of Philosophy OZSW 2013 conference 15 en 16 November 2013 OZSW Conference 2013 – Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 OZSW Conference 2013 – Erasmus University Rotterdam Table of contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................................ 2 ORGANISATION AND SPONSORS ........................................................................................................................ 8 REVIEWERS ................................................................................................................................................... 10 PROGRAMME .................................................................................................................................................. 12 KEY NOTE LECTURES ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Reason and Religion - prof. John Cottingham (University of Reading) ................................................... 18 Philosophy in Residence - prof. Jenny Slatman (Maastricht University) ................................................. 18 Philosophical Analysis and social meaning - prof. Sally Haslinger (MIT) ............................................... 18 OZSW MEMBER MEETING ............................................................................................................................... 20 Best Supervisor Award -

The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) Historical Materialism Book Series

The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Sébastien Budgen (Paris) David Broder (Rome) Steve Edwards (London) Juan Grigera (London) Marcel van der Linden (Amsterdam) Peter Thomas (London) volume 125 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hm The Dutch and German Communist Left (1900–68) ‘Neither Lenin nor Trotsky nor Stalin!’ ‘All Workers Must Think for Themselves!’ By Philippe Bourrinet leiden | boston This work is a revised and English translation from the Italian edition, entitled Alle origini del comunismo dei consigli. Storia della sinistra marxista olandese, published by Graphos publishers in Genoa in 1995. The Italian edition is again a revised version of the author’s doctorates thesis presented to the Université de Paris i in 1988. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 1570-1522 isbn 978-90-04-26977-4 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-32593-7 (e-book) Copyright 2017 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill nv incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill nv provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, ma 01923, usa. -

Taking Stock of the Published Correspondence of Victoria Lady Welby

KODIKAS / CODE Ars Semeiotica Volume 36 (2013) # No. 3–4 Gunter Narr Verlag Tübingen “It is confusion and misunderstanding that we must first attack or we must fail hopelessly in the long run.”* Taking Stock of the Published Correspondence of Victoria Lady Welby H. Walter Schmitz Victoria Lady Welby (1837–1912) 1 Introduction Victoria Lady Welby (1837–1912), the founder of significs as a sign theory with a communi- cation orientation (cf. Schmitz 1985: lxxvi–cviii), favored the minor and at the same time less strict literary forms such as the essay, essaylet, parable, and less frequently even the poem – but above all the letter – when testing, relating and discussing her ideas and thoughts. Numer- ous texts in these forms, the shortest only a few lines in length, but the longest scarcely over ten or twelve typewritten pages, have been published in their original form, often self-pub- lished, but were also points of crystallization or at least components of nearly all her publica- tions from journal articles to books. These short forms were fully retained in Grains of Sense * Lady Welby to Frederik van Eeden, Nov. 10 1909 (Van Eeden/Welby 1954: 87; cf. also Petrilli 2009: 791). 204 H. Walter Schmitz (Welby 1897). They remain easily recognizable in the short chapters of Significs and Lan- guage (Welby 1911a/1985), whereas in What is Meaning? (Welby 1903/1983), with but a few exceptions, they serve merely to provide substance for purposes of a scientific monograph. Yet the scholarly article and monograph were so unrepresentative of Lady Welby’s mind set and working methods that from about 1890 on, she repeatedly enlisted the support of her scholarly friends in framing texts of that nature – principal among whom was doubtless the philosopher, psychologist and (from 1891 to 1920) Mind editor George Frederick Stout (1860–1944). -

Jarník's Notes of the Lecture Course Allgemeine Idealtheorie by BL Van

Jarník’s Notes of the Lecture Course Allgemeine Idealtheorie by B. L. van der Waerden (Göttingen 1927/1928) Bartel Leendert van der Waerden (1903-1996) In: Jindřich Bečvář (author); Martina Bečvářová (author): Jarník’s Notes of the Lecture Course Allgemeine Idealtheorie by B. L. van der Waerden (Göttingen 1927/1928). (English). Praha: Matfyzpress, 2020. pp. 7–[32]. Persistent URL: http://dml.cz/dmlcz/404377 Terms of use: Institute of Mathematics of the Czech Academy of Sciences provides access to digitized documents strictly for personal use. Each copy of any part of this document must contain these Terms of use. This document has been digitized, optimized for electronic delivery and stamped with digital signature within the project DML-CZ: The Czech Digital Mathematics Library http://dml.cz 7 BARTEL LEENDERT VAN DER WAERDEN (1903 – 1996) Family, childhood and studies Bartel Leendert van der Waerden was born on February 2, 1903 in Amster- dam in the Netherlands. His father Theodorus van der Waerden (1876–1940) studied civil engineering at the Delft Technical University and then he taught mathematics and mechanics in Leewarden and Dordrecht. On August 28, 1901, he married Dorothea Adriana Endt (?–1942), daughter of Dutch Protestants Coenraad Endt and Maria Anna Kleij. In 1902, the young family moved to Amsterdam and Theodorus van der Waerden continued teaching mathematics and mechanics at the University of Amsterdam where he had become interes- ted in politics; all his life he was a left wing Socialist. In 1910, he was elected as a member of the Sociaal-Democratische Arbeiderspartij to the Provincial government of North Holland. -

What Moved the Signific Movement? Conceming the History of Signilics in Tho Netherlands+

KODIKAS / CODE Vdure15 (19€2) ,No, 1E Gunlor Nü V.i.t Tüblng.n What Moved the Signific Movement? Conceming the History of Signilics in tho Netherlands+ H. \ 'alter Schmitz Commemoratiotrs - days for lhis and y€ars for that - usually serve to turn oü attenlion backward toward importänt even§ and rcvered or signilicant p€ßonages. l,ooking back and rcmembering, we retospectively affirm a portion ofour life history or even the hisaory ofwestem civilizalion. Even6, persons, objec6, ideas - they are "reborn" in our memorie,s. we slage their "remsceEce", fiaaing th€m in so doilg with rellewed relevance in the here and now. But let there be no mistake; to a great oxtont it is social processes, reaching oul into our ori/n life histodes, that have directed the courso of our forgotting causing us to recall atrd rcvere this or that only very selectively. For what a society or a group (such as scholars) is prepared and able to recall says at leäsl as much about tbe rememberin8 on€s as about the object remembered. We in Germany havo oü own particular €xperience in this field. Just as renarkable, though le,§s embärrassing and brazen, is the sränce of many scholars ioward the history of science and thought. This is lho year 1987. Four hundred years ago, J. van den Vondel was born; 100 years ägo, Mullatuli died. There may be new editions of their works, commemorativo stamps, rcadings. There will surely be lengthy articles in the Sunday newspaper supplemon§ justiryiDg the social äct of commemoration and iis selectivity. -

Modern Logic 1850-1950, East and West Editors Francine F

Studies in Universal Logic Francine F. Abeles Mark E. Fuller Editors Modern Logic 1850 –1950, East and West Studies in Universal Logic Series Editor Jean-Yves Béziau (Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and Brazilian Research Council, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) Editorial Board Members Hajnal Andréka (Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest, Hungary) Mark Burgin (University of California, Los Angeles, USA) Razvan˘ Diaconescu (Romanian Academy, Bucharest, Romania) Josep Maria Font (University of Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain) Andreas Herzig (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Toulouse, France) Arnold Koslow (City University of New York, New York, USA) Jui-Lin Lee (National Formosa University, Huwei Township, Taiwan) Larissa Maksimova (Russian Academy of Sciences, Novosibirsk, Russia) Grzegorz Malinowski (University of Łód´z, Łód´z, Poland) Darko Sarenac (Colorado State University, Fort Collins, USA) Peter Schröder-Heister (University Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany) Vladimir Vasyukov (Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia) This series is devoted to the universal approach to logic and the development of a general theory of logics. It covers topics such as global set-ups for fundamental theorems of logic and frameworks for the study of logics, in particular logical matrices, Kripke structures, combination of logics, categorical logic, abstract proof theory, consequence operators, and algebraic logic. It includes also books with historical and philosophical discussions about the nature and scope of logic. Three types of books will appear in the series: graduate textbooks, research monographs, and volumes with contributed papers. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/7391 Francine F. Abeles • Mark E. Fuller Editors Modern Logic 1850-1950, East and West Editors Francine F.