Border Struggles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isurium Brigantum

Isurium Brigantum an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough The authors and publisher wish to thank the following individuals and organisations for their help with this Isurium Brigantum publication: Historic England an archaeological survey of Roman Aldborough Society of Antiquaries of London Thriplow Charitable Trust Faculty of Classics and the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Chris and Jan Martins Rose Ferraby and Martin Millett with contributions by Jason Lucas, James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven Verdonck and Lacey Wallace Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London No. 81 For RWS Norfolk ‒ RF Contents First published 2020 by The Society of Antiquaries of London Burlington House List of figures vii Piccadilly Preface x London W1J 0BE Acknowledgements xi Summary xii www.sal.org.uk Résumé xiii © The Society of Antiquaries of London 2020 Zusammenfassung xiv Notes on referencing and archives xv ISBN: 978 0 8543 1301 3 British Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Chapter 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Background to this study 1 Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data 1.2 Geographical setting 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the 1.3 Historical background 2 Library of Congress, Washington DC 1.4 Previous inferences on urban origins 6 The moral rights of Rose Ferraby, Martin Millett, Jason Lucas, 1.5 Textual evidence 7 James Lyall, Jess Ogden, Dominic Powlesland, Lieven 1.6 History of the town 7 Verdonck and Lacey Wallace to be identified as the authors of 1.7 Previous archaeological work 8 this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Fortification Renaissance: the Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne

FORTIFICATION RENAISSANCE: THE ROMAN ORIGINS OF THE TRACE ITALIENNE Robert T. Vigus Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2013 APPROVED: Guy Chet, Committee Co-Chair Christopher Fuhrmann, Committee Co-Chair Walter Roberts, Committee Member Richard B. McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Vigus, Robert T. Fortification Renaissance: The Roman Origins of the Trace Italienne. Master of Arts (History), May 2013, pp.71, 35 illustrations, bibliography, 67 titles. The Military Revolution thesis posited by Michael Roberts and expanded upon by Geoffrey Parker places the trace italienne style of fortification of the early modern period as something that is a novel creation, borne out of the minds of Renaissance geniuses. Research shows, however, that the key component of the trace italienne, the angled bastion, has its roots in Greek and Roman writing, and in extant constructions by Roman and Byzantine engineers. The angled bastion of the trace italienne was yet another aspect of the resurgent Greek and Roman culture characteristic of the Renaissance along with the traditions of medicine, mathematics, and science. The writings of the ancients were bolstered by physical examples located in important trading and pilgrimage routes. Furthermore, the geometric layout of the trace italienne stems from Ottoman fortifications that preceded it by at least two hundred years. The Renaissance geniuses combined ancient bastion designs with eastern geometry to match a burgeoning threat in the rising power of the siege cannon. Copyright 2013 by Robert T. Vigus ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and encouragement of many people. -

Tiburzio Spannocchi's Project for the Fortifications of Fuenterrabía in 1580

This paper is part of the Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Defence Sites: Heritage and Future (DSHF 2016) www.witconferences.com Tiburzio Spannocchi’s project for the fortifications of Fuenterrabía in 1580 R. T. Yáñez Pacios & V. Echarri Iribarren University of Alicante, Spain Abstract Fuenterrabía (Hondarribia) is a town located on the Franco-Spanish border. Between the 16th and 19th centuries it was considered to be one of the most outstanding strongholds in the Basque Country due to its strategic position. The bastion system of fortification was extremely prevalent in this stronghold. It was one of the first Spanish towns to adopt the incipient Renaissance designs of the bastion. The military engineers subsequently carried out continuous fortification projects that enabled the structure to withstand the advances being made in artillery and siege tactics. After the construction of the citadel of Pamplona had begun in 1571, following the design of the prestigious military engineer, Jacobo Palear Fratín and being revised by Viceroy Vespasiano Gonzaga, the afore- mentioned engineer undertook an ambitious project commissioned by Felipe II to modernise the fortifications of Fuenterrabía. Neither the plans nor the report of this project have been conserved, but in the year 2000, César Fernández Antuña published the report written by Spannocchi on the state of the fortifications of Fuenterrabía when he arrived to the Spanish peninsula, discovered in the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Zaragoza. This document conducts an in-depth analysis of Spannocchi’s project and how it was related to Fratín’s previous project. It concludes that this project encountered problems in updating the new bastions at the end of the 16th century, and identifies the factors which prevented the stronghold from being extended as was the case in Pamplona after Fratín’s project. -

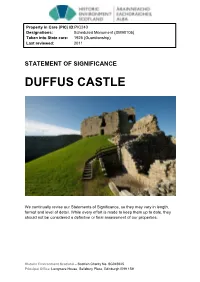

Duffus Castle Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID:PIC240 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90105) Taken into State care: 1925 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2011 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DUFFUS CASTLE We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DUFFUS CASTLE SYNOPSIS Duffus Castle is the best-preserved motte-and-bailey castle in state care. It was built c.1150 by Freskin, a Fleming who founded the powerful Moray (Murray) dynasty. -

Heritage Architecture

V. Echarri, Int. J. of Herit. Archit., Vol. 1, No. 1 (2017) 1–16 FORTIFICATION AND FRONTIER: THE PROJECT DRAWN UP BY JUAN MARTÍN ZERMEÑO FOR PUEBLA DE SANABRIA IN 1766 V. ECHARRI University of Alicante, Spain. ABSTRACT Following the death of Engineer General Jorge Próspero de Verboom in 1744 and after a few years of transition in the management of Spanish fortifications, Juan Martín Zermeño took on the role, initially with a temporary mandate, but then definitively during a second period that ran from 1766 until his death in 1772. He began this second period with a certain amount of concern because of what had taken place during the last period of conflict.T he Seven Years War (1756–1763) which had brought Spain into conflict with Portugal and England in the Caribbean had also lead to conflict episodes along the Spanish–Portuguese border. Zermeño’s efforts as a planner and general engineer gave priority to the northern part of the Span- ish–Portuguese border. After studying the territory and the existing fortifications on both sides of the border, Zermeño drew up three important projects in 1766. The outposts that needed to be reinforced were located, from north to south, at Puebla de Sanabria, Zamora and Ciudad Rodrigo, which is where he is believed to have come from. This latter township already had a modern installation built immedi- ately after the War of the Spanish Succession and reinforced with the fort of La Concepción. However, Zamora and Puebla de Sanabria had some obsolete fortifications that needed modernising. Since the middle of the 15th century Puebla de Sanabria had had a modern castle with rounded tur- rets, that of the Counts of Benavente. -

Vauban!S Siege Legacy In

VAUBAN’S SIEGE LEGACY IN THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION, 1702-1712 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jamel M. Ostwald, M.A. The Ohio State University 2002 Approved by Dissertation Committee: Professor John Rule, Co-Adviser Co-Adviser Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Co-Adviser Department of History Professor Geoffrey Parker Professor John Lynn Co-Adviser Department of History UMI Number: 3081952 ________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3081952 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ____________________________________________________________ ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ABSTRACT Over the course of Louis XIV’s fifty-four year reign (1661-1715), Western Europe witnessed thirty-six years of conflict. Siege warfare figures significantly in this accounting, for extended sieges quickly consumed short campaign seasons and prevented decisive victory. The resulting prolongation of wars and the cost of besieging dozens of fortresses with tens of thousands of men forced “fiscal- military” states to continue to elevate short-term financial considerations above long-term political reforms; Louis’s wars consumed 75% or more of the annual royal budget. Historians of 17th century Europe credit one French engineer – Sébastien le Prestre de Vauban – with significantly reducing these costs by toppling the impregnability of 16th century artillery fortresses. Vauban perfected and promoted an efficient siege, a “scientific” method of capturing towns that minimized a besieger’s casualties, delays and expenses, while also sparing the town’s civilian populace. -

Cortés After the Conquest of Mexico

CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN By RANDALL RAY LOUDAMY Bachelor of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2003 Master of Arts Midwestern State University Wichita Falls, Texas 2007 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2013 CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Dissertation Approved: Dr. David D’Andrea Dissertation Adviser Dr. Michael Smith Dr. Joseph Byrnes Dr. James Cooper Dr. Cristina Cruz González ii Name: Randall Ray Loudamy Date of Degree: DECEMBER, 2013 Title of Study: CORTÉS AFTER THE CONQUEST OF MEXICO: CONSTRUCTING LEGACY IN NEW SPAIN Major Field: History Abstract: This dissertation examines an important yet woefully understudied aspect of Hernán Cortés after the conquest of Mexico. The Marquisate of the Valley of Oaxaca was carefully constructed during his lifetime to be his lasting legacy in New Spain. The goal of this dissertation is to reexamine published primary sources in light of this new argument and integrate unknown archival material to trace the development of a lasting legacy by Cortés and his direct heirs in Spanish colonial Mexico. Part one looks at Cortés’s life after the conquest of Mexico, giving particular attention to the themes of fame and honor and how these ideas guided his actions. The importance of land and property in and after the conquest is also highlighted. Part two is an examination of the marquisate, discussing the key features of the various landholdings and also their importance to the legacy Cortés sought to construct. -

Germany from the Earliest Period Vol. 4

Germany from the Earliest Period Vol. 4 Wolfgang Menzel, Trans. Mrs. George Horrocks The Project Gutenberg EBook of Germany from the Earliest Period Vol. 4 by Wolfgang Menzel, Trans. Mrs. George Horrocks Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Germany from the Earliest Period Vol. 4 Author: Wolfgang Menzel, Trans. Mrs. George Horrocks Release Date: July, 2005 [EBook #8401] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on July 7, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GERMAN HISTORY, V4 *** Produced by Charles Franks, David King and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. GERMANY FROM THE EARLIEST PERIOD BY WOLFGANG MENZEL TRANSLATED FROM THE FOURTH GERMAN EDITION By MRS. -

Dossier De Demande D'autorisation D'exploiter

DOSSIER DE DEMANDE D’AUTORISATION D’EXPLOITER E TUDE DE D ANGERS I NSTALLATION DE STOCK AGE DE MATIERES ET D ’ OBJETS EXPLOSI BLE S Lieu - dit Bildstoecklezug 68 74 0 MUNCHHOUSE Référence : EDD - DGSCGC/2015/ 42 Indice : D Date de création : 22 / 04 /201 6 Date de révision : 27/07/2017 DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA SECURITE CIVILE ET DE LA GESTION DES CRISES Bureau du déminage Commune de MUNCHHOUSE ( HAUT - RHIN ) DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA SECURITE CIVILE ET DE LA GESTION DES CRISES Bureau du déminage - Commune de MUNCHHOUSE ( Haut - Rhin ) EDD - DGSCGC/2015/42 INDICE : D PAGE 2 Date : 27/07/2017 ETAT DES MODIFICATIONS Date Nature de la modification Auteur Indice C. COATRIEUX 22/04/2016 Version initiale A ESP CONSEIL Version modifiée suite aux remarques C. COATRIEUX 12/08/2016 B de la Sécurité Civile ESP CONSEIL Version modifiée suite aux remarques C. COATRIEUX 24/02/2017 C de la DREAL ESP CONSEIL Version modifiée suite aux remarques C. COATRIEUX 27/07/2017 D de la DREAL et de la Sécurité Civile ESP CONSEIL VISA Chef du Bureau du Déminage Document réalisé par : SAS ESP CONSEIL 8 Puy de Cornac 33720 CERONS Tél / Fax 05 56 2 7 46 9 7 [email protected] DIRECTION GENERALE DE LA SECURITE CIVILE ET DE LA GESTION DES CRISES Bureau du déminage - Commune de MUNCHHOUSE ( Haut - Rhin ) EDD - DGSCGC/2015/42 INDICE : D PAGE 3 Date : 27/07/2017 SOMMAIRE OBJET ET CHAMP D’APP LICATION 6 1.1 Objet de l’étude 6 1.2 Références 6 INFORMATIONS GENERAL ES 7 2.1 Présentation de la DGSCGC – Bureau déminage 7 2.2 Présentation du projet 9 2.3 Description des installations liées au projet 10 DESCRIPTION DE L’ENV IRONNEMENT 11 3.1 Situation 11 3.2 Environnement urbain et industriel 12 3.2.1 COMMUNES PROCHES DU SITE 12 3.2.2 ETABLISSEMENT RECEVA NT DU PUBLIC ET INST ALLATIONS OUVERTES A U PUBLIC 12 3.2.3 ZONES D’ACTIVITES 14 3.3 Voies de communication 15 3.3.1 LE RESEAU ROUTIER 15 3.3.2 LE RESEAU FERRE 15 3.3.3 LE RESEAU FLUVIAL 16 3.3.4 LE RESEAU AERIEN 17 3.4 Environnement naturel 18 3. -

Ot the Civil War

.1"/1/0-77 T>llHS USED DI DESCRIBING • FORTIFICATIONS c . Bowie Lanford. J%' . Park Historian April. 196) • Souree,,: Farl"OW ' 8 Military Encyclopedia Coggin!!' Al'In8 I< Equipment ot the Civil War • • • In fortifications, a deviee by II'hieh ~n are able to delintr their tire over the parapet. It is made jurt high enough above the terepletn to allow !\'en of med1\lJ!1 stature to fire o'rer the interior crest, The dietlnee of the tT6ad below the cre!t is tac:en, for this pul'pOse at ,,~. r feet !liz :l.nchesJ sometimes it is taken tllree inches le88 or four feet and a quarter. '!'he width of the tr-ead depends upon the nlJlllbe r ot • ranks expected to occupj'lt. In t he <h,ya of the SI'IOoth bore!! and muzzle loading muskets it Va.! made wide enough tor two ra'lks. A width at tvo feet i s wftieient for one rank. It h ulrually l1181ie three feet Vide in Dl"d1nar,y t1el d f'ortit1eation3 . The tread is M$de with a slope t o the rear, to alaow the vtter tall1n8 on it to drain off. It is connected With the terrepletn either by a slope or by stepa. Tha inclination of t he forme r is UIJIlill:y t ; it !'lay be greater if the banquette 18 low. The ramp or inclined slope 18 preferred to steps. • The banquette 1s II. step a earth Vith.1n the parapet suff iCiently high to enable the defenden. When standing upon it, to fire over the crest of the parapet Vith ea8e . -

The Impact Off Crusader Castles Upon European Western Castles

THE IMPACT OF CRUSADER CASTLES UPON EUROPEAN WESTERN CASTLES IN THE MIDDLE AGES JORDAN HAMPE MAY 2009 A SENIOR PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN- LA CROSSE Abstract: During the Middle Ages, the period from roughly AD 1000-1450, the structure of castles changed greatly from wooden motte and bailey to stone keeps and defenses within stone city walls. The reason for the change was largely influenced by the crusades as Europeans went to the Holy Lands to conquer. In addition to conquering, these kings brought back a new way of designing and fortifying their castles in England, Wales and France. Without the influence of the crusades, what we think of as true middle age castles would not exist. For my paper I will analyze the impact the crusades had on forming the middle age castles by evidence surviving in the archaeological record from before and after the crusades as well as modifications done on castles to accommodate crusader changes to show the drastic influence of crusader castle fortifications upon English, Welsh and French castles. 1 Introduction Construction of what is believed to be true middle age castles from A.D. 1000 to 1450 began as kings arrived back from the crusades to the Holy Lands, bringing with them ideas of how to make their castles grander and more easily defensible. Before the crusades William I of England was beginning to develop a new concentric style of castle beginning with the Tower of London. After the crusades many English, Welsh and French kings took the concentric concept and combined it with what they saw on the crusades and developed it to become majestic castles and fortresses like Chateau Gaillard in France, Dover Castle in England, and Caernarvon Castle in Wales. -

1. Phase < 1095 2. Phase < 1250 3. Phase < 1384 4. Phase

Die Burg Bourscheid lag auf einem nur von NW aus zugänglichen Schieferfelsen, Le château-fort de Bourscheid est situé sur un promontoire escarpé, accessible Bourscheid castle is situated on a isolated promontory, accessible only from the De burcht Bourscheid lag op een alleen vanuit het N.W. toegankelijke leisteenrots, 150 m über dem rechten Ufer der Sauer, 360 bis 380 m über dem Meeresspiegel. uniquement du nord-ouest, surplombant la rive droite de la Sûre de 150 north-west, 150 meters above the level of the river Sure and 370 meters above 150 m boven de rechte roever van de Sure en 360 tot 380 m boven de zeespiegel Die Ruinen dieser Anlage zeugen heute noch von einer bedeutenden Feste, die m, à une altitude de 360 à 380 m au-dessus de la mer. Ce manoir 17 sea level. Even today the ruins testify to an impressive fortification covering (N.N.). De ruines van deze bouwconstructie, die ongeveer 151 m lang en 53 m etwa 151 m lang und 53 m breit war, mit einer Fläche von 12.000 qm, umgeben médiéval, entouré d’un épais mur d’enceinte, muni de 11 tours, occupait 5 a surface of 12.000 square meters (151 meters long, 53 meters wide) and breed waren hat een oppervlakte van 12.000 qm, en was omgeven door een von einer starken Ringmauer mit Zwingern und 11 Türmen. une surface d’environ 12.000 m2, d’une longueur de 151 m et d’une 1 surrounded by a massive ring wall with 11 watchtowers. sterke ringmuur met afgesloten tussenruimtes en 11 torens zijn tegenwoordig Die Kernburg/Oberburg entstand um das Jahr 1000 als Ausbau einer largeur de 53 m.