Son of Sevenless Directly Links the Robo Receptor to Rac Activation to Control Axon Repulsion at the Midline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snapshot: Axon Guidance Pasterkamp R

494 1 Cell Cell ??? SnapShot: Axon Guidance 153 SnapShot: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX 1 2 , ??MONTH?? ??DATE??, 200? ©200? Elsevier Inc. 200?©200? ElsevierInc. , ??MONTH?? ??DATE??, DOI R. Jeroen Pasterkamp and Alex L. Kolodkin , April11, 2013©2013Elsevier Inc. DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.031 AUTHOR XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX 1 AFFILIATIONDepartment of XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Neuroscience and Pharmacology, Rudolf Magnus Institute of Neuroscience, University Medical Center Utrecht, 3584 CG Utrecht, The Netherlands; 2Department of Neuroscience, HHMI, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21212, USA Axon attraction and repulsion Surround repulsion Selective fasciculation Topographic mapping Self-avoidance Wild-type Dscam1 mutant Sema3A A Retina SC/Tectum EphB EphrinB P D D Mutant T A neuron N P A V V Genomic DNA P EphA EphrinA Slit Exon 4 (12) Exon 6 (48) Exon 9 (33) Exon 17 (2) Netrin Commissural axon guidance Surround repulsion of peripheral Grasshopper CNS axon Retinotectal mapping at the CNS midline nerves in vertebrates fasciculation in vertebrates Drosophila mushroom body XXXXXXXXX NEURITE/CELL Isoneuronal Sema3 Slit Sema1/4-6 Heteroneuronal EphrinA EphrinB FasII Eph Genomic DNA Pcdh-α (14) Pcdh-β (22) Pcdh-γ (22) Variable Con Variable Con Nrp Plexin ** *** Netrin LAMELLIPODIA Con DSCAM ephexin Starburst amacrine cells in mammalian retina Ras-GTP Vav See online version for legend and references. α-chimaerin GEFs/GAPs Robo FARP Ras-GDP LARG RhoGEF Kinases DCC cc0 GTPases PKA cc1 FAK Regulatory Mechanisms See online versionfor??????. Cdc42 GSK3 cc2 Rac PI3K P1 Rho P2 cc3 Abl Proteolytic cleavage P3 Regulation of expression (TF, miRNA, FILOPODIA srGAP Cytoskeleton regulatory proteins multiple isoforms) Sos Trio Pcdh Cis inhibition DOCK180 PAK ROCK Modulation of receptors’ output LIMK Myosin-II Colin Forward and reverse signaling Actin Trafcking and endocytosis NEURONAL GROWTH CONE Microtubules SnapShot: Axon Guidance R. -

Adaptive Stress Signaling in Targeted Cancer Therapy Resistance

Oncogene (2015) 34, 5599–5606 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0950-9232/15 www.nature.com/onc REVIEW Adaptive stress signaling in targeted cancer therapy resistance E Pazarentzos1,2 and TG Bivona1,2 The identification of specific genetic alterations that drive the initiation and progression of cancer and the development of targeted drugs that act against these driver alterations has revolutionized the treatment of many human cancers. Although substantial progress has been achieved with the use of such targeted cancer therapies, resistance remains a major challenge that limits the overall clinical impact. Hence, despite progress, new strategies are needed to enhance response and eliminate resistance to targeted cancer therapies in order to achieve durable or curative responses in patients. To date, efforts to characterize mechanisms of resistance have primarily focused on molecular events that mediate primary or secondary resistance in patients. Less is known about the initial molecular response and adaptation that may occur in tumor cells early upon exposure to a targeted agent. Although understudied, emerging evidence indicates that the early adaptive changes by which tumor cells respond to the stress of a targeted therapy may be crucial for tumo r cell survival during treatment and the development of resistance. Here we review recent data illuminating the molecular architecture underlying adaptive stress signaling in tumor cells. We highlight how leveraging this knowledge could catalyze novel strategies to minimize -

Regulation of the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Complex 2 (Mtorc2)

Regulation of the Mammalian Target Of Rapamycin Complex 2 (mTORC2) Inauguraldissertation Zur Erlangung der Würde eines Doktors der Philosophie vorgelegt der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Basel von Klaus-Dieter Molle aus Heilbronn, Deutschland Basel, 2006 Genehmigt von der Philosophisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät Auf Antrag von Prof. Michael N. Hall und Prof. Markus Affolter. Basel, den 21.11.2006 Prof. Hans-Peter Hauri Dekan Summary The growth controlling mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) is a conserved Ser/Thr kinase found in two structurally and functionally distinct complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. The tumor suppressor TSC1-TSC2 complex inhibits mTORC1 by acting on the small GTPase Rheb, but the role of TSC1-TSC2 and Rheb in the regulation of mTORC2 is unclear. Here we examined the role of TSC1-TSC2 in the regulation of mTORC2 in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Induced knockdown of TSC1 and TSC2 (TSC1/2) stimulated mTORC2-dependent actin cytoskeleton organization and Paxillin phosphorylation. Furthermore, TSC1/2 siRNA increased mTORC2-dependent Ser473 phosphorylation of plasma membrane bound, myristoylated Akt/PKB. This suggests that loss of Akt/PKB Ser473 phosphorylation in TSC mutant cells, as reported previously, is due to inhibition of Akt/PKB localization rather than inhibition of mTORC2 activity. Amino acids and overexpression of Rheb failed to stimulate mTORC2 signaling. Thus, TSC1-TSC2 also inhibits mTORC2, but possibly independently of Rheb. Our results suggest that mTORC2 hyperactivation may contribute to the pathophysiology of diseases such as cancer and Tuberous Sclerosis Complex. i Acknowledgement During my PhD studies in the Biozentrum I received a lot of support from many people around me who I mention here to express my gratefulness. -

The Atypical Guanine-Nucleotide Exchange Factor, Dock7, Negatively Regulates Schwann Cell Differentiation and Myelination

The Journal of Neuroscience, August 31, 2011 • 31(35):12579–12592 • 12579 Cellular/Molecular The Atypical Guanine-Nucleotide Exchange Factor, Dock7, Negatively Regulates Schwann Cell Differentiation and Myelination Junji Yamauchi,1,3,5 Yuki Miyamoto,1 Hajime Hamasaki,1,3 Atsushi Sanbe,1 Shinji Kusakawa,1 Akane Nakamura,2 Hideki Tsumura,2 Masahiro Maeda,4 Noriko Nemoto,6 Katsumasa Kawahara,5 Tomohiro Torii,1 and Akito Tanoue1 1Department of Pharmacology and 2Laboratory Animal Resource Facility, National Research Institute for Child Health and Development, Setagaya, Tokyo 157-8535, Japan, 3Department of Biological Sciences, Tokyo Institute of Technology, Midori, Yokohama 226-8501, Japan, 4IBL, Ltd., Fujioka, Gumma 375-0005, Japan, and 5Department of Physiology and 6Bioimaging Research Center, Kitasato University School of Medicine, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-0374, Japan In development of the peripheral nervous system, Schwann cells proliferate, migrate, and ultimately differentiate to form myelin sheath. In all of the myelination stages, Schwann cells continuously undergo morphological changes; however, little is known about their underlying molecular mechanisms. We previously cloned the dock7 gene encoding the atypical Rho family guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) and reported the positive role of Dock7, the target Rho GTPases Rac/Cdc42, and the downstream c-Jun N-terminal kinase in Schwann cell migration (Yamauchi et al., 2008). We investigated the role of Dock7 in Schwann cell differentiation and myelination. Knockdown of Dock7 by the specific small interfering (si)RNA in primary Schwann cells promotes dibutyryl cAMP-induced morpholog- ical differentiation, indicating the negative role of Dock7 in Schwann cell differentiation. It also results in a shorter duration of activation of Rac/Cdc42 and JNK, which is the negative regulator of myelination, and the earlier activation of Rho and Rho-kinase, which is the positive regulator of myelination. -

A Rac/Cdc42 Exchange Factor Complex Promotes Formation of Lateral filopodia and Blood Vessel Lumen Morphogenesis

ARTICLE Received 1 Oct 2014 | Accepted 26 Apr 2015 | Published 1 Jul 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms8286 OPEN A Rac/Cdc42 exchange factor complex promotes formation of lateral filopodia and blood vessel lumen morphogenesis Sabu Abraham1,w,*, Margherita Scarcia2,w,*, Richard D. Bagshaw3,w,*, Kathryn McMahon2,w, Gary Grant2, Tracey Harvey2,w, Maggie Yeo1, Filomena O.G. Esteves2, Helene H. Thygesen2,w, Pamela F. Jones4, Valerie Speirs2, Andrew M. Hanby2, Peter J. Selby2, Mihaela Lorger2, T. Neil Dear4,w, Tony Pawson3,z, Christopher J. Marshall1 & Georgia Mavria2 During angiogenesis, Rho-GTPases influence endothelial cell migration and cell–cell adhesion; however it is not known whether they control formation of vessel lumens, which are essential for blood flow. Here, using an organotypic system that recapitulates distinct stages of VEGF-dependent angiogenesis, we show that lumen formation requires early cytoskeletal remodelling and lateral cell–cell contacts, mediated through the RAC1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) DOCK4 (dedicator of cytokinesis 4). DOCK4 signalling is necessary for lateral filopodial protrusions and tubule remodelling prior to lumen formation, whereas proximal, tip filopodia persist in the absence of DOCK4. VEGF-dependent Rac activation via DOCK4 is necessary for CDC42 activation to signal filopodia formation and depends on the activation of RHOG through the RHOG GEF, SGEF. VEGF promotes interaction of DOCK4 with the CDC42 GEF DOCK9. These studies identify a novel Rho-family GTPase activation cascade for the formation of endothelial cell filopodial protrusions necessary for tubule remodelling, thereby influencing subsequent stages of lumen morphogenesis. 1 Institute of Cancer Research, Division of Cancer Biology, 237 Fulham Road, London SW3 6JB, UK. -

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early

Cellular and Molecular Signatures in the Disease Tissue of Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Stratify Clinical Response to csDMARD-Therapy and Predict Radiographic Progression Frances Humby1,* Myles Lewis1,* Nandhini Ramamoorthi2, Jason Hackney3, Michael Barnes1, Michele Bombardieri1, Francesca Setiadi2, Stephen Kelly1, Fabiola Bene1, Maria di Cicco1, Sudeh Riahi1, Vidalba Rocher-Ros1, Nora Ng1, Ilias Lazorou1, Rebecca E. Hands1, Desiree van der Heijde4, Robert Landewé5, Annette van der Helm-van Mil4, Alberto Cauli6, Iain B. McInnes7, Christopher D. Buckley8, Ernest Choy9, Peter Taylor10, Michael J. Townsend2 & Costantino Pitzalis1 1Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, Charterhouse Square, London EC1M 6BQ, UK. Departments of 2Biomarker Discovery OMNI, 3Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, Genentech Research and Early Development, South San Francisco, California 94080 USA 4Department of Rheumatology, Leiden University Medical Center, The Netherlands 5Department of Clinical Immunology & Rheumatology, Amsterdam Rheumatology & Immunology Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 6Rheumatology Unit, Department of Medical Sciences, Policlinico of the University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy 7Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8TA, UK 8Rheumatology Research Group, Institute of Inflammation and Ageing (IIA), University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2WB, UK 9Institute of -

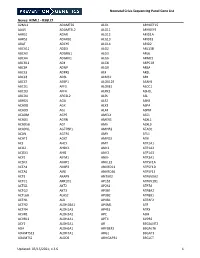

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Targeting PH Domain Proteins for Cancer Therapy

The Texas Medical Center Library DigitalCommons@TMC The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses Center UTHealth Graduate School of (Open Access) Biomedical Sciences 12-2018 Targeting PH domain proteins for cancer therapy Zhi Tan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/utgsbs_dissertations Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, Medicinal Chemistry and Pharmaceutics Commons, Neoplasms Commons, and the Pharmacology Commons Recommended Citation Tan, Zhi, "Targeting PH domain proteins for cancer therapy" (2018). The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses (Open Access). 910. https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/utgsbs_dissertations/910 This Dissertation (PhD) is brought to you for free and open access by the The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences at DigitalCommons@TMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Dissertations and Theses (Open Access) by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@TMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TARGETING PH DOMAIN PROTEINS FOR CANCER THERAPY by Zhi Tan Approval page APPROVED: _____________________________________________ Advisory Professor, Shuxing Zhang, Ph.D. _____________________________________________ -

Crit. Rev. in Biochem. and Molec. Biol. 2011

Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2011, 1–21, Early Online 2011 © 2011 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. ISSN 1040-9238 print/ISSN 1549-7798 online 00 DOI: 10.3109/10409238.2011.618113 00 000 REVIEW 000 18 June 2011 Mammalian TOR signaling to the AGC kinases 15 August 2011 Bing Su1 and Estela Jacinto2 24 August 2011 1Department of Immunobiology and The Vascular Biology and Therapeutics Program, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA and 2Department of Physiology and Biophysics, UMDNJ-RWJMS, Piscataway, NJ, USA 1040-9238 1549-7798 Abstract The mechanistic (or mammalian) target of rapamycin (mTOR), an evolutionarily conserved protein kinase, orchestrates © 2011 Informa Healthcare USA, Inc. cellular responses to growth, metabolic and stress signals. mTOR processes various extracellular and intracellular inputs as part of two mTOR protein complexes, mTORC1 or mTORC2. The mTORCs have numerous cellular targets but 10.3109/10409238.2011.618113 members of a family of protein kinases, the protein kinase (PK)A/PKG/PKC (AGC) family are the best characterized direct mTOR substrates. The AGC kinases control multiple cellular functions and deregulation of many members of BBMG this family underlies numerous pathological conditions. mTOR phosphorylates conserved motifs in these kinases to allosterically augment their activity, influence substrate specificity, and promote protein maturation and 618113 stability. Activation of AGC kinases in turn triggers the phosphorylation of diverse, often overlapping, targets that ultimately control cellular response to a wide spectrum of stimuli. This review will highlight recent findings on how mTOR regulates AGC kinases and how mTOR activity is feedback regulated by these kinases. -

Dock3 Stimulates Axonal Outgrowth Via GSK-3ß-Mediated Microtubule

264 • The Journal of Neuroscience, January 4, 2012 • 32(1):264–274 Development/Plasticity/Repair Dock3 Stimulates Axonal Outgrowth via GSK-3-Mediated Microtubule Assembly Kazuhiko Namekata, Chikako Harada, Xiaoli Guo, Atsuko Kimura, Daiji Kittaka, Hayaki Watanabe, and Takayuki Harada Visual Research Project, Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Medical Science, Tokyo 156-8506, Japan Dock3, a new member of the guanine nucleotide exchange factors, causes cellular morphological changes by activating the small GTPase Rac1. Overexpression of Dock3 in neural cells promotes axonal outgrowth downstream of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) signaling. We previously showed that Dock3 forms a complex with Fyn and WASP (Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein) family verprolin- homologous (WAVE) proteins at the plasma membrane, and subsequent Rac1 activation promotes actin polymerization. Here we show that Dock3 binds to and inactivates glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) at the plasma membrane, thereby increasing the nonphos- phorylated active form of collapsin response mediator protein-2 (CRMP-2), which promotes axon branching and microtubule assembly. Exogenously applied BDNF induced the phosphorylation of GSK-3 and dephosphorylation of CRMP-2 in hippocampal neurons. More- over, increased phosphorylation of GSK-3 was detected in the regenerating axons of transgenic mice overexpressing Dock3 after optic nerve injury. These results suggest that Dock3 plays important roles downstream of BDNF signaling in the CNS, where it regulates cell polarity and promotes axonal outgrowth by stimulating dual pathways: actin polymerization and microtubule assembly. Introduction We recently detected a common active center of Dock1ϳ4 within The Rho-GTPases, including Rac1, Cdc42, and RhoA, are best the DHR-2 domain and reported that the DHR-1 domain is nec- known for their roles in regulating the actin cytoskeleton and are essary for the direct binding between Dock1ϳ4 and WAVE1ϳ3 implicated in a broad spectrum of biological functions, such as (Namekata et al., 2010). -

Identification of Potential Key Genes and Pathway Linked with Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Based on Integrated Bioinformatics Analyses

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.20248688; this version posted December 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Identification of potential key genes and pathway linked with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on integrated bioinformatics analyses Basavaraj Vastrad1, Chanabasayya Vastrad*2 , Iranna Kotturshetti 1. Department of Biochemistry, Basaveshwar College of Pharmacy, Gadag, Karnataka 582103, India. 2. Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001, Karanataka, India. 3. Department of Ayurveda, Rajiv Gandhi Education Society`s Ayurvedic Medical College, Ron, Karnataka 562209, India. * Chanabasayya Vastrad [email protected] Ph: +919480073398 Chanabasava Nilaya, Bharthinagar, Dharwad 580001 , Karanataka, India NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.21.20248688; this version posted December 24, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Abstract Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) is neurodegenerative disease also called prion disease linked with poor prognosis. The aim of the current study was to illuminate the underlying molecular mechanisms of sCJD. The mRNA microarray dataset GSE124571 was downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were screened. -

Mutation Analysis of Son of Sevenless in Juvenile Myelomonocytic Leukemia

Letters to the Editor 1108 3 Licht JD. Reconstructing a disease: what essential features of the the development of acute promyelocytic leukemia in transgenic retinoic acid receptor fusion oncoproteins generate acute promye- mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 13306–13311. locytic leukemia? Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 73–74. 10 Sternsdorf T, Phan VT, Maunakea ML, Ocampo CB, Sohal J, 4 Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J, Stover EH, Legare RD, Cortes J et al. Silletto A et al. Forced retinoic acid receptor alpha homodimers A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 prime mice for APL-like leukemia. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 81–94. genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosino- 11 Kwok C, Zeisig BB, Dong S, So CW. Forced homo-oligomerization philic syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1201–1214. of RARalpha leads to transformation of primary hematopoietic 5 Kaufmann I, Martin G, Friedlein A, Langen H, Keller W. Human cells. Cancer Cell 2006; 9: 95–108. Fip1 is a subunit of CPSF that binds to U-rich RNA elements and 12 Palaniswamy V, Moraes KC, Wilusz CJ, Wilusz J. Nucleophosmin stimulates poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J 2004; 23: 616–626. is selectively deposited on mRNA during polyadenylation. Nat 6 Sainty D, Liso V, Cantu-Rajnoldi A, Head D, Mozziconacci MJ, Struct Mol Biol 2006; 13: 429–435. Arnoulet C et al. A new morphologic classification system for acute 13 Rego EM, Ruggero D, Tribioli C, Cattoretti G, Kogan S, Redner RL promyelocytic leukemia distinguishes cases with underlying PLZF/ et al.