Dundrennan Abbey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, C.1164-C.1560

1 The Cistercian Abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560 Victoria Anne Hodgson University of Stirling Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2016 2 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination of the Cistercian abbey of Coupar Angus, c.1164-c.1560, and its place within Scottish society. The subject of medieval monasticism in Scotland has received limited scholarly attention and Coupar itself has been almost completely overlooked, despite the fact that the abbey possesses one of the best sets of surviving sources of any Scottish religious house. Moreover, in recent years, long-held assumptions about the Cistercian Order have been challenged and the validity of Order-wide generalisations disputed. Historians have therefore highlighted the importance of dedicated studies of individual houses and the need to incorporate the experience of abbeys on the European ‘periphery’ into the overall narrative. This thesis considers the history of Coupar in terms of three broadly thematic areas. The first chapter focuses on the nature of the abbey’s landholding and prosecution of resources, as well as the monks’ burghal presence and involvement in trade. The second investigates the ways in which the house interacted with wider society outside of its role as landowner, particularly within the context of lay piety, patronage and its intercessory function. The final chapter is concerned with a more strictly ecclesiastical setting and is divided into two parts. The first considers the abbey within the configuration of the Scottish secular church with regards to parishes, churches and chapels. The second investigates the strength of Cistercian networks, both domestic and international. -

Sweetheart Abbey and Precinct Walls Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC216 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90293) Taken into State care: 1927 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2013 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE SWEETHEART ABBEY AND PRECINCT WALLS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2018 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH SWEETHEART ABBEY SYNOPSIS Sweetheart Abbey is situated in the village of New Abbey, on the A710 6 miles south of Dumfries. The Cistercian abbey was the last to be set up in Scotland. -

Your Detailed Itinerary

Romantic Scotland Romantic Your Detailed Itinerary Scotland associated with Robert Burns, where English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, Day 1 a whole range of places, centred on Day 4 Day 5 who was inspired by the waterfall the Robert Burns Birthplace Museum here. Take the road through Liddesdale in at Alloway, Ayr, are worth exploring There’s a special romance in the Loch Retrace the shore-side route as far as Scottish Borders for Hermitage for their connection to this romantic Lomond area – and it lies close to Drymen and take the A811 Return east to Aberfoyle, going north Castle, visited by Mary, Queen of figure in Scotland’s literary life. In Glasgow, to the north of the city. eastwards, turning north on the A81 over the Duke’s Pass (the A821) for Scots, then head south west via 1791 he famously wrote what is Perhaps it came about through the for the Trossachs. This is the part of Callander. Gretna Green which, like other places perhaps Scotland’s saddest and most famous Scottish song ‘The Bonnie Scotland where tourism first began at along the border, was a destination romantic song of parting – ‘Ae fond Banks of Loch Lomond’, with its the dawning of the Romantic Age for eloping couples in the days when kiss and then we sever’. poignant and romantic theme of the before the end of the 18th century, Scotland had less strict wedding laws! soldier destined never to walk with when Highland scenery was seen in a his true love again by the ‘bonnie new way – as exciting, daring and Continue west for Dumfries, with its banks’. -

Topographical Notes on Coupar Angus in Perthshire, with a Description of Archaeological Excavations

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 125 (1995), 1045-1068, fiche 3: G9-14 Abbey, marke cemeteryd an t : topographical noten so Coupar Angus in Perthshire, with a description of archaeological excavations on glebe land by the parish church Jerry O'Sullivan* with contributions by Tanya O'Sullivan & Stephen Carter ABSTRACT generalA reviewtopographythe of archaeologyand Couparof Angus Perthshirein attemptsto draw together several strands of information. chiefThe focus siteinterestof the former ofin the is Cistercian Abbey. possibilityThe settlementof earlierin periods considered.is historyThe the of Abbey brieflyis outlined. evolutionAn modern ofthe town proposed,is centred marketa on place at the Abbey gates. The final section describes identification of an early cemetery by recent archaeological excavation on glebe land by the present parish church. Excavation and publication were funded Historicby Scotland. INTRODUCTION The name Coupar is possibly derived from the Gaelic Cul-Bharr, or rear-of-the-ridge (Warden 1882, 129)e CisterciaTh . n Abbe f Coupao y r Angu sligha s site n swa do t prominenc aren a an i e which is generally low-lying and poorly drained. To the north, a long ridge rises from the modern tow overlooo nt Isle kth a river valley fro northers mit n subur t Beecba h Hill (illu. s1) Coupar Angu sfifte Abbeth h s Cisterciane housywa th f eo Scotlandn i s t enjoyeI . dlona g perio f growtdo h unti mid-14te lth h century thougd an , fortunes hit s were more mixed thereaftert i , remained, until the Reformation, one of the wealthiest of Scottish monastic houses. In 1606-7, the Abbey, wit s estatehit privilegesd an s s establishewa , a tempora s da l lordshi r Jamefo p s Elphinstone, Lord Coupar. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 Chief Social Work Officer’S Annual Report

Chief Social Work Officer’s ANNUAL REPORT 2017 - 2018 Chief Social Work Officer’s Annual Report 2 2017 - 2018 Contents 1. Summary of Performance ..................................................................................................................... 4 2. Partnership Structures/Governance Arrangements ............................................................................. 4 3. Social Services Delivery Landscape ....................................................................................................... 6 4. Resources ................................................................................................................................................ 8 5. Service Quality and Performance ......................................................................................................... 9 5.1 Personalised Services ...................................................................................................................... 9 5.2 Assistive Technology .................................................................................................................... 11 5.3 Children’s Services ........................................................................................................................ 12 5.4 Adult Services ............................................................................................................................... 15 5.5 Statutory Mental Health Service ................................................................................................ -

“Patriot”: Civic Britain, C

INTERNATIONAL REVIEW OF SCOTTISH STUDIES ISSN 1923-5755 E-ISSN 1923-5763 EDITOR J. E. Fraser, University of Guelph ASSISTANT EDITORS S. Devlin, University of Guelph C. Hartlen, University of Guelph REVIEW EDITORS M. Hudec, University of Guelph H. Wilson, University of Guelph EDITORIAL BOARD M. Brown, University of Aberdeen G. Carruthers, University of Glasgow L. Davis, Simon Fraser University E. L. Ewan, University of Guelph D. Fischlin, University of Guelph K. J. James, University of Guelph L. L. Mahood, University of Guelph A. McCarthy, University of Otago D. Nerbas, McGill University M. Penman, University of Stirling R. B. Sher, New Jersey Institute of Technology The Editors assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion made by contributors. All contents are © copyrighted by the International Review of Scottish Studies and/or their author, 2017 Book printing by Stewart Publishing & Printing Markham, Ontario • 905-294-4389 [email protected] • www.stewartbooks.com SUBMISSION OF ARTICLES FOR PUBLICATION This is a peer-reviewed, open access journal. It is listed in the Directory of Open Access Journals and is a member of the Canadian Association of Learned Journals. Directory of Open Access Journals: www.doaj.org Canadian Association of Learned Journals: www.calj-acrs.ca All manuscripts, including endnotes, captions, illustrations and supplementary information should be submitted electronically through the journal’s website: www.irss.uoguelph.ca Submission guidelines and stylistic conventions are also to be found there, along with all back issues of the journal. Manuscripts should be a maximum of 8000 words in length although shorter papers will also be considered. -

SEVERITY and EARLY ENGLISH CISTERCIAN ARCHITECTURE By

SEVERITY AND EARLY ENGLISH CISTERCIAN ARCHITECTURE By Robert Arthur Roy B.A., The University of British Columbia, 1964 B.L.S., The University of British Columbia, 1968 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of FINE ARTS We accept this thesis as conforming to the standard required from candidates for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that per• mission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publi• cation of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Fine Arts The University of British Columbia, Vancouver 8, Canada. Date 2Q April 1971 ABSTRACT It is generally" agreed that Cistercian architecture of the twelfth century is plain and simple. Many writers attribute this severity wholly to the influence of St. Bernard, without considering the political, social and economic conditions that prevailed during the early years of the Cistercian order's history. In this paper, a wider approach is taken; from a study of early Cistercian architecture in England it is suggested that the simplicity was the product of several factors, rather than the decree of one man. The paper begins with a brief resume of the events leading to the foundation of the Cistercian order and of its early development. -

126613796.23.Pdf

SC5». S, f # I PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME LI WIGTOWNSHIRE CHARTERS I960 WIGTOWNSHIRE CHARTERS Edited by R. C. REID, LL.D. EDINBURGH Printed by T. and A. Constable Ltd. Printers to the University of Edinburgh for the Scottish History Society 1960 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE This volume represents some ten years voluntary work undertaken for the National Register of Archives since that body was first formed. It has involved the examination, calendaring and indexing of all documents prior to the year 1600 of the following collections presently lodged in the Register House: Charters of the Earl of Galloway, Lochnaw (Agnew) Charters, Logan (McDowell) Charters, and Barnbarroch (Vaus) Charters; in addition to the following collections, still in private hands, Mochrum Park (Dunbar) Charters, Myrton (McCulloch) Charters, Monreith (Maxwell) Charters, the Craichlaw and Shennanton Papers, and the Cardoness and Kirkconnell Charters, as well as much unpublished material in the Scottish Record Office. I have to express my thanks to the owners and custodians for giving me the necessary access and facilities. In the presentation and editing of these documents I have received ready assistance from many quarters, but I would fail in my duty if I did not mention especially Mrs. A. I. Dunlop, LL.D., and Dr. Gordon Donaldson, who have ungrudgingly drawn on their wide experience as archivists, and Mr. Athol Murray, LL.B., of the Scottish Record Office, who has called my attention to documents and entries in the public records and even undertaken a search of the Registers of the Archbishops of York. -

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019

Arbroath Abbey Final Report March 2019 Richard Oram Victoria Hodgson 0 Contents Preface 2 Introduction 3-4 Foundation 5-6 Tironensian Identity 6-8 The Site 8-11 Grants of Materials 11-13 The Abbey Church 13-18 The Cloister 18-23 Gatehouse and Regality Court 23-25 Precinct and Burgh Property 25-29 Harbour and Custom Rights 29-30 Water Supply 30-33 Milling 33-34 The Almshouse or Almonry 34-40 Lay Religiosity 40-43 Material Culture of Burial 44-47 Liturgical Life 47-50 Post-Reformation Significance of the Site 50-52 Conclusions 53-54 Bibliography 55-60 Appendices 61-64 1 Preface This report focuses on the abbey precinct at Arbroath and its immediately adjacent appendages in and around the burgh of Arbroath, as evidenced from the documentary record. It is not a history of the abbey and does not attempt to provide a narrative of its institutional development, its place in Scottish history, or of the men who led and directed its operations from the twelfth to sixteenth centuries. There is a rich historical narrative embedded in the surviving record but the short period of research upon which this document reports did not permit the writing of a full historical account. While the physical structure that is the abbey lies at the heart of the following account, it does not offer an architectural analysis of the surviving remains but it does interpret the remains where the documentary record permits parts of the fabric or elements of the complex to be identified. This focus on the abbey precinct has produced some significant evidence for the daily life of the community over the four centuries of its corporate existence, with detail recovered for ritual and burial in the abbey church, routines in the cloister, through to the process of supplying the convent with its food, drink and clothing. -

CASTLE of PARK, GLENLUCE, DUMFRIES and GALLOWAY In

CASTLE OF PARK, GLENLUCE, DUMFRIES AND GALLOWAY In 1991 the Castle of Park was leased by Historic Scotland to the Landmark Trust, as a charity which restores and cares for historic buildings throughout Great Britain. The future maintenance of these buildings is paid for by letting them for holidays. This allows many different people, from all walks of life, to enjoy them and learn from them. Parties of up to seven people can now stay here in this very fine tower house. In 1992-93, the interior of the Castle was restored, to make it habitable again after standing empty for a hundred and fifty years. The architects in charge of the work were the Edinburgh firm of Stewart Tod and Partners; and the builders were Robison and Davidson of Dunragit. The History of the Castle The inscription over the door tells us that work began on the Castle of Park on the first day of March, 1590 (in time for a good long season's work before the next winter); and that Thomas Hay of Park and his wife Janet MacDowel were responsible for it. Thomas had been given the Park of Glenluce, land formerly belonging to Glenluce Abbey, by his father in 1572, and it is said that he took stone from the Abbey buildings for his own new house. This he built in the tall fashion of other laird's houses of the period, usually known as tower houses. Although very plain, it is on a grand scale, as is shown by the large rooms and the fine quality of the stonework. -

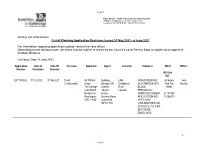

Weekly List of Decisions List of Planning Application Decisions Issued 31 May 2021 - 4 June 2021

PUBLIC Steve Rogers – Head of Economy and Development Kirkbank, English Street, Dumfries, DG1 2HS Telephone (01387) 260199 - Fax (01387) 260188 Weekly List of Decisions List of Planning Application Decisions issued 31 May 2021 - 4 June 2021 For information regarding applications please contact the case officer. Depending on the decision route, decisions may be subject to review by the Council’s Local Review Body or subject to an appeal to Scottish Ministers. List Issue Date: 9 June 2021 Application Date of Date Of Decision Applicant Agent Location Proposal Ward Officer Number Validation Decision OS Grid Ref. 20/1795/FUL 17.12.2020 01.06.2021 Grant Mr Clifford Building Little CONVERSION OF Stranraer Iona Conditionally Howe Design (UK) Cairnbrock ACCOMMODATION And The Brooke The Cottage Limited Ervie BLOCK Rhins Low Street Tayson Leswalt PREVIOUSLY Brotherton House APPROVED UNDER E:197848 Knottingley Methley Road APPLICATION NO. N:566670 WF11 9HQ Castleford 13/P/1/0430 WF10 1PA (IMPLEMENTED ON 21/05/2014) TO 3 NO. DETACHED DWELLINGS 1 PUBLIC PUBLIC Application Date of Date Of Decision Applicant Agent Location Proposal Ward Officer Number Validation Decision OS Grid Ref. 21/0067/FUL 11.03.2021 04.06.2021 Grant Mr Philip WBC Plot 4 ERECTION OF Stranraer Mary Conditionally Harrington Drawings South Cliff DWELLINGHOUSE And The Mitchell Waterside Lockside Portpatrick AND GARAGE Rhins House 38 Leigh Stranraer BUILDING AND Pincock Street DG9 8LE FORMATION OF E:200021 Street Wigan ACCESS N:553886 Euxton WN1 3BE PR7 6LR 21/0844/FUL 26.04.2021 03.06.2021 -

Investigating Years

The peaceful ruins of Dundrennan Abbey date back nearly eight hundred INVESTIGATING years. A visit here is a source of evidence and inspiration DUNDRENNAN ABBEY for a study of medieval Scotland. Information for Teachers investigating historic sites dundrennan Abbey 2 The peaceful ruins of Dundrennan brothers laboured in their gardens and Abbey date back nearly eight farms to become self-sufficient in food Timeline hundred years. A visit here is a and fuel. They became exporters of wool 1142 Cistercian abbey source of evidence and inspiration to Europe, a useful source of revenue for founded by David I at for a study of medieval Scotland. the abbey. Dundrennan Historical background With the coming of the sixteenth Late 1100s Major century the abbey was already in redevelopment of abbey It is likely that David I founded the decline. The last abbot had been church abbey at Dundrennan in 1142. It was promoted to become Bishop of 1296 Abbey swears set up as a Cistercian community or Ross and a lay administrator, or allegiance to Edward I monastery, an order established in commendator, was appointed in his France in 1098. The Cistercians were 1299 Abbey suffers losses place. With the Reformation of the through destruction committed to austerity and to following Church in 1560, the commendator, and burning by Edward’s strictly the rules of St Benedict. They set Edward Maxwell, was ordered to troops up communities in remote places and demolish the abbey buildings. Although 1523 First commendator dedicated their lives to god through he refused to do this, monastic life at - lay administrator - a ceaseless round of prayer and hard the abbey came to an end at about this appointed manual labour.