A Brief History of Public Carry in Wyoming

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firearms Firearms Play an Important Part in Ship to Ship Combat

Firearms Firearms play an important part in ship to ship combat. Historically, the pistol, musket, and the Alchemist’s Rifle musketoon—a favored boarding weapon among Price 2,000 gp; Weight 10 lb. pirates—were a staple of the sailor’s arsenal during the golden age of piracy. Older weapons, such as This wide-barreled musket fires canisters of the firelance and fireworks, would not be out of alchemist’s fire. A target hit by the cartridge takes place in a fantasy campaign, especially one where 1d4 fire damage at the start of each of its turns. A alchemists dabble in creating explosive black creature can end this damage by using its action powder. A number of new firearms are presented to make a DC 10 Dexterity check to extinguish the below, in addition to the renaissance firearms flames. introduced in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Weapon properties applicable to firearms, including the new ‘bulky’ weapon property, are included for easy reference, as are new optional rules for misfires, which are useful for balancing the introduction of firearms into your campaign. Properties Axe Musket Firearms use special ammunition, and some of Price 520 gp; Weight 12 lb. them have the burst fire, bulky, or reload property. This musket has an axe head at the end of its Ammunition. The ammunition of a firearm barrel and can be used as a battleaxe. is destroyed upon use. Firearms listed here use bullets and gunpowder, but your DM may choose Blunderbuss to forgo the use of gunpowder for the sake of simplicity. Price 450 gp; Weight 8 lb. -

A SUPPLEMENT for DUNGEONSLAYERS S by MICHAEL WOLF FIREARMS SHOTGUNS PREFACE Shotguns Are Loaded with Lead RULES for FIREARMS Shot Instead of Solid Bullets

DS-SU-02-EN IREWORK FA SUPPLEMENT FOR DUNGEONSLAYERS S BY MICHAEL WOLF FIREARMS SHOTGUNS PREFACE Shotguns are loaded with lead RULES FOR FIREARMS shot instead of solid bullets. They are feared for the extreme spread Firearms are treated similar to Dungeonslayers is an old-fashioned of projectiles but have only very other ranged weapons like bows roleplaying game, inspired by its limited range. Every target in a or crossbows. There are, alas, classic precursors from the good old 90° arc up to a distance of 5 meters some additional rules to take into days. Firearms and grenades don’t takes full damage. consideration. usually appear in typical fantasy roleplaying games, however some RELOADING WEAPONS campaign worlds are set in later DERRINGER / HOLD-OUT PISTOLS In a game of Dungeonslayers PCs epochs or incorporate elements of The Derringer is a short and small are supposed to have sufficient Steampunk. handgun with a very limited effective ammunition for their ranged range of 15 m. It is the preferred weapons. This applies to firearms My goal is to present new weapons weapon of women, assassins and too, but the reloading procedure and rules for Dungeonslayers, professional gamblers. after each firing is somewhat allowing for the integration of awkward. Reloading uses one firearms, exotic combination FLAMETHROWER action per barrel. Some situations weapons and much more into a A flamethrower is used to (fumble, wet gun powder) may Dungeonslayers campaign. squirt a long jet of pressurized, require checks to get the weapon Have fun! burning liquid onto a target. The back into working condition flamethrowers fuel is emitted as (successful MND+DX checks), Michael Wolf a jet, not as a spray. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

74- %2-42 4264

G. ELGIN. Pistol Sword. No. 254. Patented July 5, 1837. Zerezz/ W22ze war. 774 7/24 74- %2-42 4264 PEERS, photo-LTHOGRAPHER, washingtoN, d. c. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. GEO. ELGIN, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. MPROVEMENT IN THE PSTOL KNIFE OR C UTASS. Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 254, dated July 5, 1887. s To all tuhon, it inval? concern: m I construct my pistols, knives, and cutlasses Be it known that I, GEORGE ELGIN, of the in any of the known forms, and combine them city, county, and State of New York, late of in the following manner: The handle being the city of Macon, county of Bibb and State the same, the barrel and blade are combined of Georgia, have invented a new and useful by tongue and groove with a screw or screws, instrument called the Pistol-Knife or Pistol or the barrel and blade can be made solid, or Cutlass; and I do hereby declare that the foll the two can be soldered in such manner as to lowing is a true and exact description. be firm and Substantial. The barrel is com The nature of my invention consists in com bined on the top or back of the knife or cut bining the pistol and Bowie knife, or the pis lass, and may extend to any distance to suit tol and cutlass, in such manner that it can be the maker or manufacturer. used with as much ease and facility as either What I claim as my invention, and desire the pistol, knife, or cutlass could be if sepa to secure by Letters Patent, is rate, and in an engagement, when the pistol The combination of the pistol and blade in is discharged, the knife (or cutlass) can be the manner above described, using any metals brought into immediate use without changing for the manufacture of those articles which or drawing, as the two instruments are in the will produce the intended effect. -

Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation-Making

n today’s United States, the legacy of the American Revolution looms large. From presidential speeches to bestselling biographies, from conservative politics to school pageants, everybody knows something about the Revolution. Yet what was a messy, protracted, = divisive, and destructive war has calcified into a t the Iglorified founding moment of the American nation. h e g Disparate events with equally diverse participants Revolution have been reduced to a few key scenes and characters, RememberinMemory, History, and Nation Making from Independence to the Civil War presided over by well-meaning and wise old men. In this lively collection of essays, historians and literary scholars consider how the first three generations of American citizens interpreted their = nation’s origins. They show how the memory of the Revolution became politicized early in the nation’s EditEd by history, as different interests sought to harness its Michael A. McDonnell meaning for their own ends. No single faction succeeded, and at the outbreak of the Civil War the Clare Corbould American people remained divided over how to Frances M. Clarke remember the Revolution. and MIChAel A. MCDoNNell is associate professor W. Fitzhugh Brundage of history at the University of Sydney. ClARe CoRBoUlD is Australian Research Council Future Fellow at Monash University, Melbourne. FRANCeS M. ClARke is senior lecturer at the University of Sydney. W. FITzhUgh BRUNDAge is professor of history at the University of North Carolina, Chapel hill. a volume in the series Public history in historical Perspective Cover design by Sally Nichols Cover painting by emanuel leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware, oil on canvas, 1851, 149 x 255 in. -

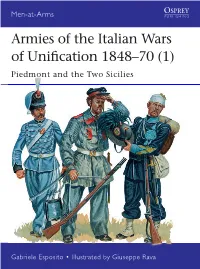

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy. -

Pro Patria Commemorating Service

PRO PATRIA COMMEMORATING SERVICE Forward Representative Colonel Governor of South Australia His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le, AO Colonel Commandant The Royal South Australia Regiment Brigadier Tim Hannah, AM Commanding Officer 10th/27th Battalion The Royal South Australia Regiment Lieutenant Colonel Graham Goodwin Chapter Title One Regimental lineage Two Colonial forces and new Federation Three The Great War and peace Four The Second World War Five Into a new era Six 6th/13th Light Battery Seven 3rd Field Squadron Eight The Band Nine For Valour Ten Regimental Identity Eleven Regimental Alliances Twelve Freedom of the City Thirteen Sites of significance Fourteen Figures of the Regiment Fifteen Scrapbook of a Regiment Sixteen Photos Seventeen Appointments Honorary Colonels Regimental Colonels Commanding Officers Regimental Sergeants Major Nineteen Commanding Officers Reflections 1987 – 2014 Representative Colonel His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO Governor of South Australia His Excellency was born in Central Vietnam in 1954, where he attended school before studying Economics at the Dalat University in the Highlands. Following the end of the Vietnam War, His Excellency, and his wife, Lan, left Vietnam in a boat in 1977. Travelling via Malaysia, they were one of the early groups of Vietnamese refugees to arrive in Darwin Harbour. His Excellency and Mrs Le soon settled in Adelaide, starting with three months at the Pennington Migrant Hostel. As his Tertiary study in Vietnam was not recognised in Australia, the Governor returned to study at the University of Adelaide, where he earned a degree in Economics and Accounting within a short number of years. In 2001, His Excellency’s further study earned him a Master of Business Administration from the same university. -

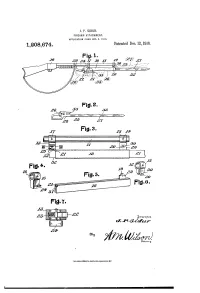

Patented Dec. 12, 1916

J, P, SDUR, FIREARM ATTACHMENT, APPLICATION FED OCT. 2, 1916. 1,208,674. Patented Dec. 12, 1916, Fig.1. - - aé aa, 7 ze v 47 - 24, 27 It i? On 250 I rvue in tot v/-Z Zazzezzr elttorne rive Norris Prices co, PMoTourna, wastnorow.re. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. JOHN P. SIDUR, OF WARE, IVIASSACHUSETTS, FIREARNI ATTACHINIENT. 1,208,674. Specification of Letters Patent. Patented Dec. 12, 1916. Application filed October 2, 1916. Serial No. 123,829. To all whom it may concern; collar 13 is attached to the barrel 11 adja Be it known that I, JoHN P. SIDUR, a cent the muzzle thereof, being secured in subject of the Emperor of Austria-Hungary, place by means of a screw 14 while a mount residing at Ware, in the county of Hamp ing catch 15 is secured to the barrel 11 rear 5 shire and State of Massachusetts, have in Wardly of the member 12 being in the form 60 vented certain new and useful Improve of a collar 16 surrounding the said barrel, followingments in Firearm is a specification. Attachments, of which the Secured in position by a screw 17. A tubular This invention relates to certain new and Scabbard 18 substantially rectangular in cross-section is provided with a perforated 65 10 useful improvements in firearm attachments. lug 19 at its forward end pivotally at The primary object of the invention is tached to spaced depending ears 20 of the the provision of a pistol sword attachment pivoting Support 12. The rear end of the for rifles whereby the Sword member is em Scabbard 18 is provided with an incut notch ployed as a bayonet when the pistol Sword 21 adapted for the reception of the latch 15 is attached to the rifle. -

Kaplan Auctions 115 Dunottar Street, Sydenham, 2192, Johannesburg Po Box 28913, Sandringham, 2131, R.S.A

KAPLAN AUCTIONS 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192, JOHANNESBURG PO BOX 28913, SANDRINGHAM, 2131, R.S.A. TEL: +27 11 640 6325 / 485 2195 FAX: +27 11 640 3427 E-MAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] and [email protected] Please insist on a reply. WEBSITE ADDRESS: www.aleckaplan.co.za AUCTION B81 SALE OF MEDALS, BADGES, MILITARIA & COINS th 29 MARCH 2017 TO BE HELD 06:00 PM AT OUR PREMISES – 115 DUNOTTAR STREET, SYDENHAM, 2192 JOHANNESBURG THE LOTS WILL BE ON VIEW AT OUR PREMISES –ONLY BY APPOINTMENT. BIDDING PROCEDURE NO BIDS WILL BE ACCEPTED AFTER 12 NOON ON DAY OF AUCTION NO BIDS WILL BE PLACED WITHOUT COPY OF IDENTITY DOCUMENT 1. The Auctioneer’s decision is final. 2. Please ensure that you quote the correct lot number and recipient’s name when bidding by post. Mistakes will not be corrected after the sale. 3. This is a live auction and bids may be submitted in writing by fax, letter or e-mail, for those who cannot attend in person. 4. All items will be sold to the highest bidder. 5. Reserves have been fixed by the seller but should a reserve, in the opinion of a possible buyer be too high, I will be pleased to submit a reasonable offer to the seller, should the lot otherwise be unsold. 6. Lots have been carefully graded. Should anyone not be satisfied with the grading, such an item may be returned to us within 7 days of receipt thereof. Your payment will be refunded immediately after the goods have been received. -

Banning America's Rifle: an Assault on the Second Amendment?

Banning America’s Rifle: An Assault on the Second Amendment? By Stephen P. Halbrook Civil Rights Practice Group The AR-15 rifle has aptly been called “America’s Rifle.” It is the most popular rifle in the United States, owned and used by millions of law-abiding citizens. Does prohibiting it infringe on About the Author: the right of the people to keep and bear arms as guaranteed by the Second Amendment? Stephen P. Halbrook is the author of several books on the Second This article begins with an examination of the meanings of Amendment and the right to bear arms, including The Right to term “assault weapon,” features that some lawmakers and activists Bear Arms: A Constitutional Right of the People or a Privilege of have claimed define such weapons, and the rarity of their use in the Ruling Class?; The Founders’ Second Amendment: Origins of the crime. It then analyzes how the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence Rights to Bear Arms; and Freedmen, the Fourteenth Amendment, on the Second Amendment, which protects firearms in common & the Right to Bear Arms, 1866-1876 (reissued as Securing Civil use for lawful purposes, precludes bans on such firearms. After Rights). He argued Printz v. United States, 521 U.S. 898 (1997), that, it examines the text, history, and tradition of the Second and represented a majority of members of Congress as amici curiae Fourteenth Amendments to show that the right keeps pace with in District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570 (2008), and was and continues to exist as technological improvements are made counsel for plaintiffs-appellants in Heller v. -

Glossary of Firearm Terminology

VIRGINIA GUN COLLECTORS ASSOCIATION GLOSSARY OF FIREARMS COLLECTING TERMS Marc Gorelick VGCA A ACCOUTREMENT - Equipment carried by soldiers on the outside of their uniform, such as belts, ammunition pouches, bayonet scabbards, or canteens, but not weapons. ACCURIZE or ACCURIZING - The process of altering a firearm to improve its accuracy. ACTION - The mechanism and method that manipulates, loads, locks, extracts and ejects cartridges and/or seals the breech. Actions are broadly classified as either manual or self-loading and are generally categorized by the type of mechanism used. Manual actions are single shot or repeater. Single shot actions include dropping block (tilting or falling) rolling block, break, hinged (such as a trapdoor), and bolt. Repeater actions include revolver, bolt (turn-bolt or strait-pull), lever, pump and slide. Self-loading actions are semiautomatic or automatic. ADJUSTABLE SIGHT - A firearm sight that can be adjusted for windage and/or elevation so that the shooter’s point of aim and the projectile’s point of impact coincide at the target. Only the rear sight is adjustable on a majority of firearms, but front sights may also be adjustable. AIR CHAMBER (See LIGHTENING GROOVE) – A 19th century U.S. Ordnance Department the term for a groove cut out of the inside of a rifle’s wooden forend or a carbine’s forearm in order to make the firearm lighter. AIR GUN – A long arm or handgun that uses compressed air to fire a projectile. The earliest known air guns date to the 16th century. The compressed air was kept in a chamber in the buttstock or in a round metal ball attached to the underside of the barrel near the breech. -

The Age of Flintlock the Age of Flintlock

TheTheThe AgeAgeAge ofofof FlintlockFlintlockFlintlock FirearmsFirearmsFirearms forforfor D&DD&DD&D 5E5E5E Sample file 1 Table of Contents Topic Page Introduction 2 Firearm Properties 3 Weapon Descriptions 4 Weapon Table 5 Special Weapon Properties 6 Ammunition 6 Throwables 8 Firearm Modifications 8 Conclusion 9 Introduction It's no secret that Dungeons and Dragons is a game centered around medieval fantasy, with the most common weapons in most worlds being weapons from those respective time periods. But what if you wanted more options than bows and magic in terms of ranged combat? What if you wanted your campaign world to be set during the Age of Exploration or the Industrial Revolution and have weapons appropriate to those eras? What if you wanted a medieval setting with a technologically superior civilization having access to firearms? What if you were running a Steampunk styled game using D&D? Whatever the reason, you want firearms in your game, not the brushed over simplistic version found in the DMG, but a fleshed out system with plenty of firearms, special ammunition, and thought out customization. If so, look no further. I originally made this home-brewed firearm system for my own home game, a historically authentic game set during the Golden Age of Piracy in the early 18th century. Not only did I create a system catered to weapons of the time, I also took some historic liberties and included weapons all the way up to the mid 19th century. Not only that, but I created special ammunition for the firearms, a firearm modification system, and several different types of bombs for my players to enjoy.