Remembering the Revolution: Memory, History, and Nation-Making

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Firearms Firearms Play an Important Part in Ship to Ship Combat

Firearms Firearms play an important part in ship to ship combat. Historically, the pistol, musket, and the Alchemist’s Rifle musketoon—a favored boarding weapon among Price 2,000 gp; Weight 10 lb. pirates—were a staple of the sailor’s arsenal during the golden age of piracy. Older weapons, such as This wide-barreled musket fires canisters of the firelance and fireworks, would not be out of alchemist’s fire. A target hit by the cartridge takes place in a fantasy campaign, especially one where 1d4 fire damage at the start of each of its turns. A alchemists dabble in creating explosive black creature can end this damage by using its action powder. A number of new firearms are presented to make a DC 10 Dexterity check to extinguish the below, in addition to the renaissance firearms flames. introduced in the Dungeon Master’s Guide. Weapon properties applicable to firearms, including the new ‘bulky’ weapon property, are included for easy reference, as are new optional rules for misfires, which are useful for balancing the introduction of firearms into your campaign. Properties Axe Musket Firearms use special ammunition, and some of Price 520 gp; Weight 12 lb. them have the burst fire, bulky, or reload property. This musket has an axe head at the end of its Ammunition. The ammunition of a firearm barrel and can be used as a battleaxe. is destroyed upon use. Firearms listed here use bullets and gunpowder, but your DM may choose Blunderbuss to forgo the use of gunpowder for the sake of simplicity. Price 450 gp; Weight 8 lb. -

A SUPPLEMENT for DUNGEONSLAYERS S by MICHAEL WOLF FIREARMS SHOTGUNS PREFACE Shotguns Are Loaded with Lead RULES for FIREARMS Shot Instead of Solid Bullets

DS-SU-02-EN IREWORK FA SUPPLEMENT FOR DUNGEONSLAYERS S BY MICHAEL WOLF FIREARMS SHOTGUNS PREFACE Shotguns are loaded with lead RULES FOR FIREARMS shot instead of solid bullets. They are feared for the extreme spread Firearms are treated similar to Dungeonslayers is an old-fashioned of projectiles but have only very other ranged weapons like bows roleplaying game, inspired by its limited range. Every target in a or crossbows. There are, alas, classic precursors from the good old 90° arc up to a distance of 5 meters some additional rules to take into days. Firearms and grenades don’t takes full damage. consideration. usually appear in typical fantasy roleplaying games, however some RELOADING WEAPONS campaign worlds are set in later DERRINGER / HOLD-OUT PISTOLS In a game of Dungeonslayers PCs epochs or incorporate elements of The Derringer is a short and small are supposed to have sufficient Steampunk. handgun with a very limited effective ammunition for their ranged range of 15 m. It is the preferred weapons. This applies to firearms My goal is to present new weapons weapon of women, assassins and too, but the reloading procedure and rules for Dungeonslayers, professional gamblers. after each firing is somewhat allowing for the integration of awkward. Reloading uses one firearms, exotic combination FLAMETHROWER action per barrel. Some situations weapons and much more into a A flamethrower is used to (fumble, wet gun powder) may Dungeonslayers campaign. squirt a long jet of pressurized, require checks to get the weapon Have fun! burning liquid onto a target. The back into working condition flamethrowers fuel is emitted as (successful MND+DX checks), Michael Wolf a jet, not as a spray. -

Social Life in the Early Republic: a Machine-Readable Transcription

Library of Congress Social life in the early republic vii PREFACE peared to them, or recall the quaint figures of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton and Mrs. Madison in old age, or the younger faces of Cora Livingston, Adèle Cutts, Mrs. Gardiner G. Howland, and Madame de Potestad. To those who have aided her with personal recollections or valuable family papers and letters the author makes grateful acknowledgment, her thanks being especially due to Mrs. Samuel Phillips Lee, Mrs. Beverly Kennon, Mrs. M. E. Donelson Wilcox, Miss Virginia Mason, Mr. James Nourse and the Misses Nourse of the Highlands, to Mrs. Robert K. Stone, Miss Fanny Lee Jones, Mrs. Semple, Mrs. Julia F. Snow, Mr. J. Henley Smith, Mrs. Thompson H. Alexander, Miss Rosa Mordecai, Mrs. Harriot Stoddert Turner, Miss Caroline Miller, Mrs. T. Skipwith Coles, Dr. James Dudley Morgan, and Mr. Charles Washington Coleman. A. H. W. Philadelphia, October, 1902. ix CONTENTS Chapter Page I— A Social Evolution 13 II— A Predestined Capital 42 Social life in the early republic http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbcb.29033 Library of Congress III— Homes and Hostelries 58 IV— County Families 78 V— Jeffersonian Simplicity 102 VI— A Queen of Hearts 131 VII— The Bladensburg Races 161 VII— Peace and Plenty 179 IX— Classics and Cotillions 208 X— A Ladies' Battle 236 XI— Through Several Administrations 267 XII— Mid-Century Gayeties 296 xi ILLUSTRATIONS Page Mrs. Richard Gittings, of Baltimore (Polly Sterett) Frontispiece From portrait by Charles Willson Peale, owned by her great-grandson, Mr. D. Sterett Gittings, of Baltimore. Mrs. Gittings eyes are dark brown, the hair dark brown, with lighter shades through it; the gown of delicate pink, the sleeves caught up with pearls, the sash of a gray shade. -

August 6, 2003, Note: This Description Is Not the One

Tudor Place Manuscript Collection Martha Washington Papers MS-3 Introduction The Martha Washington Papers consist of correspondence related to General George Washington's death in 1799, a subject file containing letters received by her husband, and letters, legal documents, and bills and receipts related to the settlement of his estate. There is also a subject file containing material relating to the settlement of her estate, which may have come to Tudor Place when Thomas Peter served as an executor of her will. These papers were a part of the estate Armistead Peter placed under the auspices of the Carostead Foundation, Incorporated, in 1966; the name of the foundation was changed to Tudor Place Foundation, Incorporated, in 1987. Use and rights of the papers are controlled by the Foundation. The collection was processed and the register prepared by James Kaser, a project archivist hired through a National Historical Records and Publications grant in 1992. This document was reformatted by Emily Rusch and revised by Tudor Place archivist Wendy Kail in 2020. Tudor Place Historic House & Garden | 1644 31st Street NW | Washington, DC 20007 | Telephone 202-965-0400 | www.tudorplace.org 1 Tudor Place Manuscript Collection Martha Washington Papers MS-3 Biographical Sketch Martha Dandridge (1731-1802) married Daniel Parke Custis (1711-1757), son of John Custis IV, a prominent resident of Williamsburg, Virginia, in 1749. The couple had four children, two of whom survived: John Parke Custis (1754-1781) and Martha Parke Custis (1755/6-1773). Daniel Parke Custis died in 1757; Martha (Dandridge) Custis married General George Washington in 1759and joined him at Mount Vernon, Virginia, with her two children. -

Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1993 Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves Mary Geraghty College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, African History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Geraghty, Mary, "Domestic Management of Woodlawn Plantation: Eleanor Parke Custis Lewis and Her Slaves" (1993). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625788. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-jk5k-gf34 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMESTIC MANAGEMENT OF WOODLAWN PLANTATION: ELEANOR PARKE CUSTIS LEWIS AND HER SLAVES A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of American Studies The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Mary Geraghty 1993 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts -Ln 'ln ixi ;y&Ya.4iistnh A uthor Approved, December 1993 irk. a Bar hiara Carson Vanessa Patrick Colonial Williamsburg /? Jafhes Whittenburg / Department of -

Lee Mansion NATIONAL MEMORIAL

Lee Mansion NATIONAL MEMORIAL Arlington National Cemete ry VIRGINIA by a wide central hall. A large formal Mount Vernon. The view from the por seven Lee children were born here. By drawing room with two fine marble fire tico he pronounced unrivaled, entreating the will of George Washington Parke Cus places lies south of this hall, while to the Mrs. Custis never to sacrifice any of the tis, who died in 1857, the estate of Arling north of it can be seen the family dining fine trees. General Lafayette returned ton was bequeathed to his daughter for Lee Mansion National Memorial room and family parlor separated by a again to Arlington House in 1825 as the her lifetime, and afterward to his eldest north and south partition broken by three guest of the Custises for several weeks. grandson and namesake, George Washing graceful arches. The second story is also ton Custis Lee. divided by a central hall on either side of Lt. Robert E. Lee's Marriage Never a thrifty farmer and an easygoing In this Mansion, which became his home when he married Mary which there are two bedrooms and accom Custis, Robert E. Lee wrote his resignation from the United States master, requiring little of his slaves, Mr. panying dressing rooms. A small room On June 30, 1831, Mary Ann Randolph Army in April 1861, to join the cause of Virginia and the South. Custis' death found the Arlington planta Custis, only child of the Custis family at used as a linen closet is at the end of this tion sadly run down. -

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1

The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 1 The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Pirates' Who's Who Giving Particulars Of The Lives and Deaths Of The Pirates And Buccaneers Author: Philip Gosse Release Date: October 17, 2006 [EBook #19564] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PIRATES' WHO'S WHO *** Produced by Suzanne Shell, Christine D. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net Transcriber's note. Many of the names in this book (even outside quoted passages) are inconsistently spelt. I have chosen to retain the original spelling treating these as author error rather than typographical carelessness. THE PIRATES' The Pirates' Who's Who, by Philip Gosse 2 WHO'S WHO Giving Particulars of the Lives & Deaths of the Pirates & Buccaneers BY PHILIP GOSSE ILLUSTRATED BURT FRANKLIN: RESEARCH & SOURCE WORKS SERIES 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science 51 BURT FRANKLIN NEW YORK Published by BURT FRANKLIN 235 East 44th St., New York 10017 Originally Published: 1924 Printed in the U.S.A. Library of Congress Catalog Card No.: 68-56594 Burt Franklin: Research & Source Works Series 119 Essays in History, Economics & Social Science -

Rehabilitation of Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial South

Rehabilitation of Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial South Dependency/Slave Quarters - Discovery of a Subfloor Storage Pit Shrine Supplementary Section 106 Archeological Investigations Related to the 2017-2020 Rehabilitation Program George Washington Memorial Parkway Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial Arlington County, Virginia Matthew R. Virta, Cultural Resources Program Manager National Park Service - George Washington Memorial Parkway 2021 Cover Graphics (clockwise from upper left): Fireplace and Subfloor Pit Location, South Dependency West Room Slave Quarters, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial – NPS Photograph by B. Krueger 2019 adapted by M. Virta, National Park Service-George Washington Memorial Parkway Drawing of Previous Archeological Excavations Showing Fireplace and Subfloor Pit Excavation Unit Illustrating Positioning of Bottles Discovered, South Dependency West Room Slave Quarters, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial – NPS Drawing by M. Virta 2020, National Park Service-George Washington Memorial Parkway, based on Louis Berger Group, Inc. drawing and B. Krueger illustration Selina and Thornton Gray – from National Park Service Museum Management Program Exhibit, https://www.nps.gov/museum/exhibits/arho/index.html Elevation Drawings of South Dependency/Slave Quarters, Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial – National Park Service Historic American Building Survey Collections HABS VA 443A; https://www.loc.gov/item/va1924/. Rehabilitation of Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial South Dependency/Slave Quarters - Discovery of a Subfloor Storage Pit Shrine Supplementary Section 106 Archeological Investigations Related to the 2017-2020 Rehabilitation Program Virginia Department of Historic Resources File # 2015-1056 Archeological Site # 44AR0017 George Washington Memorial Parkway Arlington House, the Robert E. -

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in the Corcoran Gallery of Art

A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art VOLUME I THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C. A Catalogue of the Collection of American Paintings in The Corcoran Gallery of Art Volume 1 PAINTERS BORN BEFORE 1850 THE CORCORAN GALLERY OF ART WASHINGTON, D.C Copyright © 1966 By The Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. 20006 The Board of Trustees of The Corcoran Gallery of Art George E. Hamilton, Jr., President Robert V. Fleming Charles C. Glover, Jr. Corcoran Thorn, Jr. Katherine Morris Hall Frederick M. Bradley David E. Finley Gordon Gray David Lloyd Kreeger William Wilson Corcoran 69.1 A cknowledgments While the need for a catalogue of the collection has been apparent for some time, the preparation of this publication did not actually begin until June, 1965. Since that time a great many individuals and institutions have assisted in com- pleting the information contained herein. It is impossible to mention each indi- vidual and institution who has contributed to this project. But we take particular pleasure in recording our indebtedness to the staffs of the following institutions for their invaluable assistance: The Frick Art Reference Library, The District of Columbia Public Library, The Library of the National Gallery of Art, The Prints and Photographs Division, The Library of Congress. For assistance with particular research problems, and in compiling biographi- cal information on many of the artists included in this volume, special thanks are due to Mrs. Philip W. Amram, Miss Nancy Berman, Mrs. Christopher Bever, Mrs. Carter Burns, Professor Francis W. -

74- %2-42 4264

G. ELGIN. Pistol Sword. No. 254. Patented July 5, 1837. Zerezz/ W22ze war. 774 7/24 74- %2-42 4264 PEERS, photo-LTHOGRAPHER, washingtoN, d. c. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. GEO. ELGIN, OF NEW YORK, N. Y. MPROVEMENT IN THE PSTOL KNIFE OR C UTASS. Specification forming part of Letters Patent No. 254, dated July 5, 1887. s To all tuhon, it inval? concern: m I construct my pistols, knives, and cutlasses Be it known that I, GEORGE ELGIN, of the in any of the known forms, and combine them city, county, and State of New York, late of in the following manner: The handle being the city of Macon, county of Bibb and State the same, the barrel and blade are combined of Georgia, have invented a new and useful by tongue and groove with a screw or screws, instrument called the Pistol-Knife or Pistol or the barrel and blade can be made solid, or Cutlass; and I do hereby declare that the foll the two can be soldered in such manner as to lowing is a true and exact description. be firm and Substantial. The barrel is com The nature of my invention consists in com bined on the top or back of the knife or cut bining the pistol and Bowie knife, or the pis lass, and may extend to any distance to suit tol and cutlass, in such manner that it can be the maker or manufacturer. used with as much ease and facility as either What I claim as my invention, and desire the pistol, knife, or cutlass could be if sepa to secure by Letters Patent, is rate, and in an engagement, when the pistol The combination of the pistol and blade in is discharged, the knife (or cutlass) can be the manner above described, using any metals brought into immediate use without changing for the manufacture of those articles which or drawing, as the two instruments are in the will produce the intended effect. -

By Eleanor Lee Templeman Reprinted from the Booklet Prepared for the Visit of the Virginia State Legislators to Northern Virginia, January 1981

THE HERITAGE OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA By Eleanor Lee Templeman Reprinted from the booklet prepared for the visit of the Virginia State Legislators to Northern Virginia, January 1981. The documented history of Northern Virginia goes back to John Smith's written description of his exploration of the Potomac in 1608 that took him to Little Falls, the head of Tidewater at the upper boundary of Arlington Coun ty. Successive charters issued to the Virginia Company in 1609 and 1612 granted jurisdiction over all territory lying 200 miles north and south of Point Comfort, "all that space and circuit of land lying from the seacoast of the precinct aforesaid, up into the land throughout from sea to sea, west and northwest." The third charter of 1612 included Bermuda. The first limitations upon the extent of the "Kingdom of Virginia," as it was referred to by King Charles I, came in 1632 when he granted Lord Baltimore a proprietorship over the part that became Maryland. The northeastern portion of Virginia included one of America's greatest land grants, the Northern Neck Proprietary of approximately six million acres. In 1649, King Charles II, a refugee in France because of the English Civil War, granted to seven loyal followers all the land between the Potomac and Rap pahannock Rivers. (Although the term, "Northern Neck" is usually applied to . that portion south of Fredericksburg, the largest portion is in Northern Virginia.) Charles II, then in command of the British Navy, was about to launch an attack to recover the English throne. His power, however, was nullified by Cromwell's decisive victory at Worcester in 1650. -

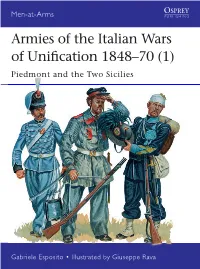

Armies of the Italian Wars of Unification 1848–70 (1)

Men-at-Arms Armies of the Italian Wars of Uni cation 1848–70 (1) Piedmont and the Two Sicilies Gabriele Esposito • Illustrated by Giuseppe Rava GABRIELE ESPOSITO is a researcher into military CONTENTS history, specializing in uniformology. His interests range from the ancient HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 3 Sumerians to modern post- colonial con icts, but his main eld of research is the military CHRONOLOGY 6 history of Latin America, • First War of Unification, 1848-49 especially in the 19th century. He has had books published by Osprey Publishing, Helion THE PIEDMONTESE ARMY, 1848–61 7 & Company, Winged Hussar • Character Publishing and Partizan Press, • Organization: Guard and line infantry – Bersaglieri – Cavalry – and he is a regular contributor Artillery – Engineers and Train – Royal Household companies – to specialist magazines such as Ancient Warfare, Medieval Cacciatori Franchi – Carabinieri – National Guard – Naval infantry Warfare, Classic Arms & • Weapons: infantry – cavalry – artillery – engineers and train – Militaria, Guerres et Histoire, Carabinieri History of War and Focus Storia. THE ITALIAN ARMY, 1861–70 17 GIUSEPPE RAVA was born in • Integration and resistance – ‘the Brigandage’ Faenza in 1963, and took an • Organization: Line infantry – Hungarian Auxiliary Legion – interest in all things military Naval infantry – National Guard from an early age. Entirely • Weapons self-taught, Giuseppe has established himself as a leading military history artist, THE ARMY OF THE KINGDOM OF and is inspired by the works THE TWO SICILIES, 1848–61 20 of the great military artists, • Character such as Detaille, Meissonier, Rochling, Lady Butler, • Organization: Guard infantry – Guard cavalry – Line infantry – Ottenfeld and Angus McBride. Foreign infantry – Light infantry – Line cavalry – Artillery and He lives and works in Italy.