Total Nephroureterocystectomy and Urethrectomy Due to Urothelial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glickman Urological & Kidney Institute

C L E V E GLICKMAN UROLOGICAL L A N D C L I N I C & KIDNEY INSTITUTE | G L I C K 2019 Year in Review M The Cleveland Clinic Foundation A N 9500 Euclid Ave. / AC311 U R O Cleveland, OH 44195 L O G I C A L & K I D N E Y I N S T I T U T E | 2 0 1 9 Y E A R I N R E V I E W 19-URL-5068 22877_CCFBCH_19URL4030_19URL5068_ACG.indd 29-31 2/6/20 3:06 PM CONTENTS 3 Glickman Kidney & Urological Institute at a Glance 7 Message from the Chairman 9 Two Clinical Trials, One Ambitious Goal to Personalize Kidney Medicine 11 A New Paradigm for Advanced Prostate Cancer Clinical Trials 13 Another Landmark Year for Cleveland Clinic’s Kidney Transplant Program 15 Getting It Right: Nephrologists Are Working to Minimize the ‘White-Coat Effect’ for Patients with Hypertension 17 ‘A FitBit for the Bladder’: UroMonitor Takes Monitoring Out of the Clinic 19 Virtual Reality Tool to Offer New Way of Understanding Renal Physiology 21 First Kidney Transplant Performed Using Single-Port Robot 22 2019 Achievements 28 Resources for Physicians ON THE COVER Georges Nakhoul, MD, Director of the Center for Chronic Kidney Disease, launched a virtual reality program to enhance the renal physiology learning experience for trainees. 22877_CCFBCH_19URL4030_19URL5068_ACG.indd 32-34 2/6/20 3:06 PM CLEVELAND CLINIC GLICKMAN UROLOGICAL & KIDNEY INSTITUTE | 3 Glickman Urological AT A GLANCE & Kidney Institute The Glickman Urological BY THE NUMBERS & Kidney Institute’s (2019) activities encompass a unique combination of high- 132,663 volume and challenging OUTPATIENT VISITS clinical cases, extensive basic and translational scientific efforts, and 14,098 innovative laboratory SURGICAL CASES research conducted in an environment that nurtures the future leaders of its 21,255 DIALYSIS TREATMENTS specialties. -

EAU Guidelines Primary Urethral Carcinomas V2

Guidelines on Primary Urethral Carcinoma G. Gakis, J.A. Witjes, E. Compérat, N.C. Cowan, M. De Santis, T. Lebret, M.J. Ribal, A. Sherif © European Association of Urology 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 3 2. METHODOLOGY 3 3. LEVEL OF EVIDENCE AND GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION 3 4. EPIDEMIOLOGY 4 5. ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS 4 6. HISTOPATHOLOGY 5 7. CLASSIFICATION 5 7.1 TNM staging system 5 7.2 Tumour grade 6 8. SURVIVAL 6 8.1 Long-term survival after primary urethral carcinoma 6 8.2 Predictors of survival in primary urethral carcinoma 6 9. DIAGNOSIS AND STAGING 7 9.1 History 7 9.2 Clinical examination 7 9.3 Urinary cytology 7 9.4 Diagnostic urethrocystoscopy and biopsy 7 9.5 Radiological imaging 7 9.6 Regional lymph nodes 7 10. TREATMENT OF LOCALISED PRIMARY URETHRAL CARCINOMA 8 10.1 Treatment of localised primary urethral carcinoma in males 8 10.2 Treatment of localised urethral carcinoma in females 8 10.2.1 Urethrectomy and urethra-sparing surgery 8 10.2.2 Radiotherapy 8 11. MULTIMODAL TREATMENT IN ADVANCED URETHRAL CARCINOMA 9 11.1 Preoperative cisplatinum-based chemotherapy 9 11.2 Preoperative chemoradiotherapy in locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the urethra 9 12. TREATMENT OF UROTHELIAL CARCIMONA OF THE PROSTATE 10 13. FOLLOW-UP 10 14. REFERENCES 10 15. ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE TEXT 15 2 PRIMARY URETHRAL CARCINOMAS - MARCH 2013 1. INTRODUCTION The European Association of Urology (EAU) Guidelines Group on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer has prepared these guidelines to deliver current evidence-based information on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with primary urethral carcinoma (UC). -

Summary of Services and Availability (By Location)

UPMC | University of Pittsburgh Medical Center For Reference Only UROLOGY 2013 Summary of Services and Availability (by location) Each location has sufficient space, equipment, staffing and financial resources in place or available in sufficient time as required to support each requested privilege. On an ongoing basis, the organization consistently determines the resources necessary for each requested privilege related to the facility's scope of service. Please review the following Summary of Services and Availability by Location prior to making your selections. If a facility is specifically identified below as NOT having a privilege/service available, you will NOT be considered for that privilege at that individual facility. Any request made that is identified as not available at an individual site will be considered Not Applicable for that site(s), and will be identified as such on your final approved Delineation of Privileges form. “x” means Privilege is Available at that location. “C” means contractual arrangement restricts granting this privilege. “N/A” means Privilege Not Available at that location. Facility Codes: UHOC= UPMC St. Margaret Harmar Outpatient Center Privilege UHOC Core privileges X Consultation Privileges N/A SURGERY OF THE KIDNEY, ADRENAL, URETER, AND BLADDER Biopsy, all techniques X Nephrotomy/pyelotomy/ureterotomy/ cystotomy for X stent placement, stone extraction, drainage abscess, biopsy, fulgeration, insertion of radioactive material Percutaneous nephroscopy, and other percutaneous X catheter techniques Nephrectomy, -

Dataset for Tumours of the Urinary Collecting System (Renal Pelvis, Ureter

Dataset for histopathological reporting of tumours of the urinary collecting system (renal pelvis, ureter, urinary bladder and urethra) August 2021 Authors: Dr Murali Varma, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff Dr Jonathan H Shanks, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Dr Ashish Chandra, Guys and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London Dr Lorna McWilliam, Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Unique document number G044 Document name Dataset for tumours of the urinary collecting system (renal pelvis, ureter, urinary bladder and urethra) Version number 3 Produced by Each of the authors is a consultant histopathologist with a special interest in urological pathology. Dr Murali Varma is a founder member and Chairman of the British Association of Urological Pathologists (BAUP), organises biannual uropathology courses on prostate and bladder pathology, and has published several original and review papers related to urological pathology. Dr Jonathan H Shanks regularly speaks at national and international meetings and has co- authored over 95 publications, mostly in the field of urological pathology. Dr Ashish Chandra is co-author of ACP Best Practice: Cut up and reporting of bladder cancer specimens and is on the NICE Clinical Guidelines Group for diagnosis and clinical management of bladder cancer. Dr Lorna McWilliam is a founder member of BAUP and speaks on bladder and prostate pathology at their biannual courses. She helped to develop national and regional guidelines for best practice in urological pathology. Date active August 2021 (to be implemented within three months) Date for review August 2024 Comments This document will replace the 2nd edition published in 2013. In accordance with the College’s pre-publications policy, this document was on the Royal College of Pathologists’ website for consultation from 27 May to 24 June 2021. -

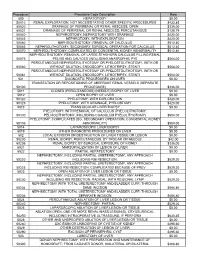

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500

Procedure Procedure Code Description Rate 500 HEPATOTOMY $0.00 50010 RENAL EXPLORATION, NOT NECESSITATING OTHER SPECIFIC PROCEDURES $433.85 50020 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; OPEN $336.00 50021 DRAINAGE OF PERIRENAL OR RENAL ABSCESS; PERCUTANIOUS $128.79 50040 NEPHROSTOMY, NEPHROTOMY WITH DRAINAGE $420.00 50045 NEPHROTOMY, WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50060 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF CALCULUS $512.40 50065 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; SECONDARY SURGICAL OPERATION FOR CALCULUS $512.40 50070 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; COMPLICATED BY CONGENITAL KIDNEY ABNORMALITY $512.40 NEPHROLITHOTOMY; REMOVAL OF LARGE STAGHORN CALCULUS FILLING RENAL 50075 PELVIS AND CALYCES (INCLUDING ANATROPHIC PYE $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50080 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 PERCUTANEOUS NEPHROSTOLITHOTOMY OR PYELOSTOLITHOTOMY, WITH OR 50081 WITHOUT DILATION, ENDOSCOPY, LITHOTRIPSY, STENTI $504.00 501 DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES ON LIVER $0.00 TRANSECTION OR REPOSITIONING OF ABERRANT RENAL VESSELS (SEPARATE 50100 PROCEDURE) $336.00 5011 CLOSED (PERCUTANEOUS) (NEEDLE) BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 5012 OPEN BIOPSY OF LIVER $0.00 50120 PYELOTOMY; WITH EXPLORATION $420.00 50125 PYELOTOMY; WITH DRAINAGE, PYELOSTOMY $420.00 5013 TRANSJUGULAR LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 PYELOTOMY; WITH REMOVAL OF CALCULUS (PYELOLITHOTOMY, 50130 PELVIOLITHOTOMY, INCLUDING COAGULUM PYELOLITHOTOMY) $504.00 PYELOTOMY; COMPLICATED (EG, SECONDARY OPERATION, CONGENITAL KIDNEY 50135 ABNORMALITY) $504.00 5014 LAPAROSCOPIC LIVER BIOPSY $0.00 5019 OTHER DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES -

Urethral Carcinoma Recurrence in Ileal Orthotopic Neobladder: Urethrectomy and Conversion in a Continent Pouch with Abdominal Stoma

Case Report Urol Int 1999;62:213–216 Received: June 19, 1998 Accepted after revision: March 8, 1999 Urethral Carcinoma Recurrence in Ileal Orthotopic Neobladder: Urethrectomy and Conversion in a Continent Pouch with Abdominal Stoma Riccardo Bartoletti a Alessandro Natali a Mauro Gacci a Michelangelo Rizzoa Cesare Selli b Departments of Urology, aUniversity of Florence, and bUniversity of Udine, Italy Key Words incidence of complications such as nighttime inconti- Bladder carcinoma W Ileal neobladder W Urethral nence, high postvoid volume, urinary infections, lithiasis, carcinoma recurrence or long-term augmentation of reservoir capacity [1]. Ure- thral carcinoma recurrences are reported in about 5% of the patients treated with orthotopic urinary diversion and Abstract are often due to an inadequate preoperative evaluation of A patient who had previously undergone ileal neoblad- disease and localization of bladder carcinoma at the blad- der with Studer technique presented an urethral recur- der neck [2]. rence of a transitional cell carcinoma. Further surgical treatment consisted of urethrectomy and creation of an intussuscepted ileal loop which was anastomosed to the Case Report pouch and provided a continence mechanism allowing A 68-year-old male patient, who originally presented a T N M self-catheterization. 2 0 0 (G2) bladder tumor and underwent 12 months earlier orthotopic Copyright © 1999 S. Karger AG, Basel ileal neobladder diversion according to Studer, was admitted to our institution with hematuria. A cystourethrogram showed an urethral lesion (fig. 1a). Com- Introduction puted tomography and magnetic resonance imaging confirmed the presence of a solid lesion measuring about 3 ! 2 cm, infiltrating the corpus spongiosum (fig. -

W27: Female Urethra: Challenging Scenarios Workshop Chair: Paulo Palma, Brazil 30 August 2018 12:05 - 13:05

W27: Female urethra: challenging scenarios Workshop Chair: Paulo Palma, Brazil 30 August 2018 12:05 - 13:05 Start End Topic Speakers 12:05 12:15 Primary obstruction of the bladder neck Mauro Cervigni 12:15 12:25 Urethral stenosis: which approach for which patient? Paulo Palma 12:25 12:35 Urethral diverticula Cassio Riccetto 12:35 12:45 Urethral reconstruction in transgender patients Ömer Acar 12:45 13:05 Discussion of challenge cases Paulo Palma Cassio Riccetto Mauro Cervigni Ömer Acar Aims of Workshop To present a practical approach to female damaged urethra including strictures, diverticula, defunctionalized and tethered urethra in non-neurogenic and neurogenic scenarios. The learning process will be based on the discussion videos and clinical cases. Learning Objectives Objective 1- To diagnosis and treat primary bladder neck obstruction. Objective 2- To select the proper technique for female urethra stenosis. Objective 3- Awareness of the transgender urethra. Learning Outcomes At the end of the workshop the attendees should be able to diagnose and manage female urethra problems properly, should it be functional or anatomical. Select the proper technique for each patient and be aware of the transgender urethra. Target Audience urologists, gynecologists, urogynecologists Advanced/Basic Advanced Conditions for Learning This is a clinical oriented course addressing the female and transgender urethra based on clinical scenarios and surgical techniques. Suggested Learning before Workshop Attendance None. Suggested Reading https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28990728 World J Urol. 2017 Jun;35(6):991-995. doi: 10.1007/s00345-016-1947-7. Epub 2016 Oct 4. Female urethral stricture: a contemporary series. -

Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer

Guidelines on Muscle-invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer J.A. Witjes (Chair), E. Compérat, N.C. Cowan, M. De Santis, G. Gakis, N. James, T. Lebrét, A. Sherif, A.G. van der Heijden, M.J. Ribal Guidelines Associates: M. Bruins, V. Hernandez, E. Veskimäe © European Association of Urology 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 5 1.1 Aims and scope 5 1.2 Panel Composition 5 1.3 Available publications 5 1.4 Publication history and summary of changes 5 1.4.1 Publication history 5 1.4.2 Summary of changes 5 2. METHODS 6 2.1 Data identification 6 2.2 Peer review 6 3. EPIDEMIOLOGY, AETIOLOGY AND PATHOLOGY 6 3.1 Epidemiology 6 3.2 Aetiology 6 3.2.1 Tobacco smoking 6 3.2.2 Occupational exposure to chemicals 7 3.2.3 Radiotherapy 7 3.2.4 Dietary factors 7 3.2.5 Bladder schistosomiasis and chronic urinary tract infection 7 3.2.6 Gender 7 3.2.7 Genetic factors 8 3.2.8 Conclusions and recommendations for epidemiology and risk factors 8 3.3 Pathology 8 3.3.1 Handling of transurethral resection and cystectomy specimens 8 3.3.2 Pathology of muscle-invasive bladder cancer 9 3.3.3 Recommendations for the assessment of tumour specimens 9 4. STAGING AND CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS 9 4.1 Pathological staging 9 4.2 Tumour, node, metastasis classification 10 5. DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION 10 5.1 Primary diagnosis 10 5.1.1 Symptoms 10 5.1.2 Physical examination 10 5.1.3 Bladder imaging 10 5.1.4 Urinary cytology and urinary markers 11 5.1.5 Cystoscopy 11 5.1.6 Transurethral resection of invasive bladder tumours 11 5.1.7 Second resection 11 5.1.8 Concomitant prostate cancer 11 5.1.9 Specific recommendations for the primary assessment of presumably invasive bladder tumours 11 5.2 Imaging for staging of MIBC 12 5.2.1 Local staging of MIBC 12 5.2.1.1 MRI for local staging of invasive bladder cancer 12 5.2.1.2 CT imaging for local staging of MIBC 12 5.2.2 Imaging of lymph nodes in MIBC 12 5.2.3 Upper urinary tract urothelial carcinoma 13 5.2.4 Distant metastases at sites other than lymph nodes 13 5.2.5 Future developments 13 5.2.6 Conclusion and recommendations for staging in MIBC 13 6. -

Urogenital and Urinary Surgical Procedures

UROGENITAL AND URINARY SURGICAL PROCEDURES Urogenital and Urinary Surgical ProceduresApril 1, 2015 PREAMBLE - KIDNEY AND UPPER URINARY TRACT 1. No additional claim should be made for nephroscopy when done at the time of pyelolithotomy or nephrolithotomy. This does not apply to nephroscopy done in conjunction with codes listed under "Percutaneous - Procedures." 2. In a routine surgical approach to the kidney and related procedures, no additional claim should be made for rib resection carried out for access purposes. 3. When an adrenalectomy is performed in conjunction with a nephrectomy, and is incidental to the removal of the kidney, there should be no additional claim for the adrenalectomy. April 1, 2015 T1 Amd 12 Draft 1 UROGENITAL AND URINARY SURGICAL PROCEDURES KIDNEY AND UPPER URINARY TRACT Asst Surg Anae # E752 - with repeat surgery on kidney at least 30 days after previous kidney surgery......................................................................................................add 83.25 INCISION # Z601 Renal biopsy, needle ............................................................................................... 143.55 6 # S401 Drainage of kidney abscess..................................................................................... 7 411.30 7 # S402 Drainage of perinephric abscess ............................................................................. 7 267.60 7 # S403 Exploration of renal and peri-renal tissues (with or without biopsy or unroofing of cyst) .................................................................................................................. -

Villoglandular Adenocarcinoma of Urethra with Negative CK7 Marker: Rare Disease in Atypical Location

Crimson Publishers Case Report Wings to the Research Villoglandular Adenocarcinoma of Urethra with Negative CK7 Marker: Rare Disease in Atypical Location Matheus WE*, Ferruccio AA, Matheus MB, Almeida Braga D and Ferreira U Departments of Surgery and Division of Urology, Brazil ISSN: 2578-0395 Abstract Urethral cancer is a rare disease that affects predominantly males and the black race. The case report refers to a female patient of 75 years who had a history of dysuria and urethral pain. After an investigation with urethrocytoscopy and biopsy, a histopathological diagnosis of villograndular adenocarcinoma was CK7 expression. In a literary review, few cases of this particularly histological type where published about theidentified. urethra The and immunohistochemical none of them exhibited study the tumor identified marker the CK7 presence negative. of beta-catenin and the absence of Keywords: Adenocarcinoma; Urethra; Villograndular; CK7 Introduction Urethral cancer is a rare disease representing less than 1% of genitourinary tumors. It *Corresponding author: affects with a higher frequency male and the black race [1]. Studies show that its estimated From the Departments of Surgery and prevalence in North America is 4.3 cases per million men and 1.5 cases per million women. The Matheus WE, Sciences, Brazil Division of Urology, School of Medical carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma [2], this last one with an incidence World Health Organization (WHO) histologically classifies the urethral tumors as urothelial Submission: August 05, 2019 lower than 5% of the cases [3]. The urethral neoplasm is considered challenging to diagnose, Published: September 19, 2019 and urinary retention. These symptoms may be confused with urinary infection and lead due to the nonspecific symptoms it may present such as dysuria, hematuria, polaciuria Volume 3 - Issue 1 to a diagnosis in advanced stages of the disease [1,3]. -

UCLA Urology UPDATE

UCLA Urology UPDATE Left: A kidney transplant patient exam room at the Connie Frank Transplant Center; right: at the center’s ribbon-cutting ceremony (l. to r.): Gregory Zeiger, Connie’s Frank’s brother; Connie Frank; Evan Thompson, Ms. Frank’s husband; Bradley Zeiger, Ms. Frank’s brother; Dr. David T. Feinberg, then-president of UCLA Health; Dr. Gabriel Danovitch, professor of medicine and director of kidney and kidney/pancreas transplantation; Chancellor Gene D. Block; and Dr. Jeffrey Veale, associate professor of urology and director of the UCLA Kidney Exchange Program. Summer 2015 New Spaces Promote Comfort, VOL. 26 | NO. 3 Convenience, and Better Care Alumni Profile p4 UCLA Urology is growing. Healthy at Every Age p4 n Westwood and Santa Monica, and for patients with wide-ranging urological Letter from the Chair p5 needs, the department is expanding access to its services with new and larger spaces. But size is only part of the story. Through a purposeful and coordinated Septembeard p6 Ieffort, the new facilities are bringing together diverse teams of experts and trainees in ways that promote more communication and, as a result, enhanced training and clinical Donor Spotlight p6 care. And through more attractive and centralized facilities, the growth is dramatically improving the patient experience. Kudos p7 “The best way to achieve our missions of teaching, and practice of urology in the 21st century. That State of the Art Meeting p8 research and clinical care is to offer a state-of-the- means not only the most advanced diagnostic art environment for our patients, practitioners and and therapeutic equipment, but also spaces that trainees,” says Mark S. -

Urethral Stricture Score Is Associated with Anterior Urethroplasty Complexity and Outcome

Urethral Stricture Score is Associated with Anterior Urethroplasty Complexity and Outcome Amjad Alwaal,* Thomas H. Sanford, Catherine R. Harris, E. Charles Osterberg, Jack W. McAninch and Benjamin N. Breyer From the Departments of Urology, King Abdulaziz University (AA), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and University of California-San Francisco (AA, THS, CRH, ECO, JWM, BNB), San Francisco, California Purpose: Several surgical techniques are available to treat anterior urethral stricture. The choice of surgical technique largely depends on the severity of Abbreviations and Acronyms stricture disease. The U-score (urethral stricture score) is based on urethral ¼ stricture characteristics, namely length (1 to 3 points), number (1 or 2 points), LS lichen sclerosus location (1 or 2 points) and etiology (1 or 2 points), which are tallied to provide a Accepted for publication December 1, 2015. total score of 4 to 9 points. Our aim was to identify whether the U-score system is No direct or indirect commercial incentive predictive of the surgical complexity and outcome of anterior urethroplasty. associated with publishing this article. Materials and Methods: We retrospectively reviewed the records of all patients The corresponding author certifies that, when applicable, a statement(s) has been included in who underwent anterior urethroplasty from 2002 to 2012 by examining our pro- the manuscript documenting institutional review spectively collected urethroplasty database. We calculated the U-score and looked board, ethics committee or ethical review board for an association with surgical complexity, recurrent stricture and time to study approval; principles of Helsinki Declaration were followed in lieu of formal ethics committee recurrence. We defined recurrent stricture as the need for a secondary procedure.