Tagore, Poet and Humanist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

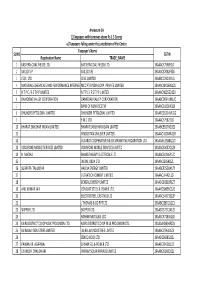

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Reading Rabindranath Tagore's Gitanjali: Meanings for Our Troubled, Pandemic Stricken Times

ISSN 25820427 (Online) Special Issue No. 1 March, 2021 A bi-lingual peer reviewed academic journal http://www.ensembledrms.in Article Type: Research Article Article Ref. No.: 20113000443RF https://doi.org/10.37948/ensemble-2021-sp1-a016 (RE)READING RABINDRANATH TAGORE'S GITANJALI: MEANINGS FOR OUR TROUBLED, PANDEMIC STRICKEN TIMES Tapashree Ghosh1 Abstract: The COVID 19 pandemic is far from over. The second wave of the virus is already adversely affecting counties such as England, France, Germany, and the USA. In India, people are suffering from the widespread impact of this disease for the last nine months. It has deeply affected our life, livelihood, health, economy, environment, and mental health. This grim scenario is not only specific to our country but can be witnessed globally. At this critical juncture, literature is extremely important as it can lift us from the nadir of depression and the abyss of nothingness. Hence, while critically engaging with the sub-theme ‘Pandemic and Literature’ we should not limit our studies to texts dealing with crises, pandemics and apocalypse. We must broaden our perspective to include texts that can emotionally heal us and generate feelings of positivity, faith, strength, and peace. Hence, this paper re-reads Tagore’s Gitanjali from the present position of being sufferers of a global crisis. The text is timeless and our contemporary. It contains Tagore’s deep engagement with philosophy and spirituality. We should re-read it and fetch newer meanings relevant to our present context. It is relevant and a necessary read for both ‘the home and the world’. Article History: Submitted on 30 Nov 2020 | Accepted on 9 February 2021| Published online on 17 April 2021 Keywords: Anxiety, Death, Fear, Heal, Spirituality, Peace, Salutation, Strength “The mind is very restless, turbulent, strong and obstinate, O Krishna. -

From Gitanjali to Song Offerings: Interrogating the Politics of Translation in the Light of Colonial Interaction

From Gitanjali to Song Offerings: Interrogating the Politics of Translation in the Light of Colonial Interaction Urmi Sengupta1 In English prose there is a magic which seems to transmute my Bengali verses into something which is original again in a different manner. Therefore, it not only satisfies me but gives me delight to assist my poems in their English birth....Fundamental idea is the same, but the vision changes. A poem can only be relived in a different atmosphere (Mitra 390) The above mentioned lines quoted from a letter of Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) addressed to D. J. Anderson spell out beautifully the nuances of the role played by Tagore as a translator of his collection of Bangla geeti-kavita titled Gitanjali (1910) into English prose. Song Offerings (also containing a few selected poems from nine of his earlier collections of poetry Gitimalya, Kalpana, Chaitali, Kheya, Naivedya, Shishu, Achalayatan , Utsarga and Swaran ) which was first published by Indian Society, London in November, 1912 and later by Macmillan and Company, London in March, 1913 received unprecedented appreciation in the West and had already been reprinted ten times within a span of a few months before it was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in November,1913. Of the two main standpoints that strive to explain this high acclaim for Song Offerings in the target language-culture , one is enunciated clearly by the Nobel Committee of 1913 in their citation which declares “Because of his profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse, by which, with consummate skill, he has made his poetic thought, expressed in his own English words, a part of the 1 Urmi Sengupta is working as a Junior Research Scholar in the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, Kolkata and pursuing PhD from the same. -

Deliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: in Vista of Education Dr

International Journal of Research in Arts and Science, Vol. 1, No. 2, August 2015 6 Deliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: In Vista of Education Dr. Tapas Pal and Dr. Sanat Kumar Rath Abstract--- Gurudevas role in the liberation of women was states in no uncertain terms that there should be equality in a determining one. He uncovered the dilemma of women and education. “Whatever is worth knowing is knowledge. It argued for their independence through his letters, short should be known equally by men and women not for the sake stories, and essays. Through his novels, he was able to of practical utility, but for the sake of knowing the desire to construct new and vital female role models to motivate a new know is the law of human nature.(Shiksha, vol.1). generation of Bengali women. Later, by his act of admitting Extra-curricular Activities such as the 1910 Drama Lakshmir females into his Santiniketan Ashram education, he became an Puja innovative pioneer in coeducation. As Santiniketan expanded to include women as students Keywords--- Liberation of Women, Ashram Education and village welfare as objectives, curriculum innovations were required. These often took place through extra-curricular activities such as the 1910 drama Lakshmir puja, which was I. INTRODUCTION staged and performed by female students. Tagore brought in dance teacher from Banaras to train the girls and when they URUDEVA’S role in the liberation of women was a left, he personally taught them. Gdetermining one. He uncovered the dilemma of women and argued for their independence through his letters, short ‘Nari-Bhavana’ stories, and essays. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

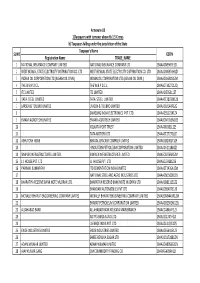

Annexure-1A 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores a) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the Centre Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. EASTERN COAL FIELDS LTD. 19AAACE7590E1ZI 2 SAIL (D.S.P) SAIL (D.S.P) 19AAACS7062F6Z6 3 CESC LTD. CESC LIMITED 19AABCC2903N1ZL 4 MATERIALS CHEMICALS AND PERFORMANCE INTERMEDIARIESMCC PTA PRIVATE INDIA CORP.LIMITED PRIVATE LIMITED 19AAACM9169K1ZU 5 N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED N T P C / F S T P P LIMITED 19AAACN0255D1ZV 6 DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION DAMODAR VALLEY CORPORATION 19AABCD0541M1ZO 7 BANK OF NOVA SCOTIA 19AAACB1536H1ZX 8 DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED DHUNSERI PETGLOBAL LIMITED 19AAFCD5214M1ZG 9 E M C LTD 19AAACE7582J1Z7 10 BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED BHARAT SANCHAR NIGAM LIMITED 19AABCB5576G3ZG 11 HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED 19AAACH1004N1ZR 12 GUJARAT COOPERATIVE MILKS MARKETING FEDARATION LTD 19AAAAG5588Q1ZT 13 VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED VODAFONE MOBILE SERVICES LIMITED 19AAACS4457Q1ZN 14 N MADHU BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LTD 19AAACB4146P1ZC 15 JINDAL INDIA LTD 19AAACJ2054J1ZL 16 SUBRATA TALUKDAR HALDIA ENERGY LIMITED 19AABCR2530A1ZY 17 ULTRATECH CEMENT LIMITED 19AAACL6442L1Z7 18 BENGAL ENERGY LIMITED 19AADCB1581F1ZT 19 ANIL KUMAR JAIN CONCAST STEEL & POWER LTD.. 19AAHCS8656C1Z0 20 ELECTROSTEEL CASTINGS LTD 19AAACE4975B1ZP 21 J THOMAS & CO PVT LTD 19AABCJ2851Q1Z1 22 SKIPPER LTD. SKIPPER LTD. 19AADCS7272A1ZE 23 RASHMI METALIKS LTD 19AACCR7183E1Z6 24 KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. KAIRA DISTRICT CO-OP MILK PRO.UNION LTD. 19AAAAK8694F2Z6 25 JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED JAI BALAJI INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACJ7961J1Z3 26 SENCO GOLD LTD. 19AADCS6985J1ZL 27 PAWAN KR. AGARWAL SHYAM SEL & POWER LTD. 19AAECS9421J1ZZ 28 GYANESH CHAUDHARY VIKRAM SOLAR PRIVATE LIMITED 19AABCI5168D1ZL 29 KARUNA MANAGEMENT SERVICES LIMITED 19AABCK1666L1Z7 30 SHIVANANDAN TOSHNIWAL AMBUJA CEMENTS LIMITED 19AAACG0569P1Z4 31 SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LIMITED SHALIMAR HATCHERIES LTD 19AADCS6537J1ZX 32 FIDDLE IRON & STEEL PVT. -

FINAL DISTRIBUTION.Xlsx

Annexure-1B 1)Taxpayers with turnover above Rs 1.5 Crores b) Taxpayers falling under the jurisdiction of the State Taxpayer's Name SL NO GSTIN Registration Name TRADE_NAME 1 NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LIMITED NATIONAL INSURANCE COMPANY LTD 19AAACN9967E1Z0 2 WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD WEST BENGAL STATE ELECTRICITY DISTRIBUTION CO. LTD 19AAACW6953H1ZX 3 INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) INDIAN OIL CORPORATION LTD.(ASSAM OIL DIVN.) 19AAACI1681G1ZM 4 THE W.B.P.D.C.L. THE W.B.P.D.C.L. 19AABCT3027C1ZQ 5 ITC LIMITED ITC LIMITED 19AAACI5950L1Z7 6 TATA STEEL LIMITED TATA STEEL LIMITED 19AAACT2803M1Z8 7 LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED LARSEN & TOUBRO LIMITED 19AAACL0140P1ZG 8 SAMSUNG INDIA ELECTRONICS PVT. LTD. 19AAACS5123K1ZA 9 EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED EMAMI AGROTECH LIMITED 19AABCN7953M1ZS 10 KOLKATA PORT TRUST 19AAAJK0361L1Z3 11 TATA MOTORS LTD 19AAACT2727Q1ZT 12 ASHUTOSH BOSE BENGAL CRACKER COMPLEX LIMITED 19AAGCB2001F1Z9 13 HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED. 19AAACH1118B1Z9 14 SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. SIMPLEX INFRASTRUCTURES LIMITED. 19AAECS0765R1ZM 15 J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD J.J. HOUSE PVT. LTD 19AABCJ5928J2Z6 16 PARIMAL KUMAR RAY ITD CEMENTATION INDIA LIMITED 19AAACT1426A1ZW 17 NATIONAL STEEL AND AGRO INDUSTRIES LTD 19AAACN1500B1Z9 18 BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. BHARATIYA RESERVE BANK NOTE MUDRAN LTD. 19AAACB8111E1Z2 19 BHANDARI AUTOMOBILES PVT LTD 19AABCB5407E1Z0 20 MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED MCNALLY BHARAT ENGGINEERING COMPANY LIMITED 19AABCM9443R1ZM 21 BHARAT PETROLEUM CORPORATION LIMITED 19AAACB2902M1ZQ 22 ALLAHABAD BANK ALLAHABAD BANK KOLKATA MAIN BRANCH 19AACCA8464F1ZJ 23 ADITYA BIRLA NUVO LTD. 19AAACI1747H1ZL 24 LAFARGE INDIA PVT. LTD. 19AAACL4159L1Z5 25 EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED EXIDE INDUSTRIES LIMITED 19AAACE6641E1ZS 26 SHREE RENUKA SUGAR LTD. 19AADCS1728B1ZN 27 ADANI WILMAR LIMITED ADANI WILMAR LIMITED 19AABCA8056G1ZM 28 AJAY KUMAR GARG OM COMMODITY TRADING CO. -

Nation and Imagination

CHAPTER 6 Nation and Imagination THIS CHAPTER moves out into three concentric circles. The innermost cir- cle tells the story of a certain literary debate in Bengal in the early part of the twentieth century. This was a debate about distinctions between prose, poetry, and the status of the real in either, and it centered on the writings of Rabindranath Tagore. Into these debatesÐand here is my second cir- cleÐI read a global history of the word ªimagination.º Benedict Ander- son's book Imagined Communities has made us all aware of how crucial the category ªimaginationº is to the analysis of nationalism.1 Yet, com- pared to the idea of community, imagination remains a curiously undis- cussed category in social science writings on nationalism. Anderson warns that the word should not be taken to mean ªfalse.º2 Beyond that, how- ever, its meaning is taken to be self-evident. One aim of this chapter is to open up the word for further interrogation and to make visible the heterogenous practices of seeing we often bring under the jurisdiction of this one European word, ªimagination.º My third and last move in the chapter is to build on this critique of the idea of imagination an argument regarding a nontotalizing conception of the political. To breathe heteroge- neity into the word ªimagination,º I suggest, is to allow for the possibility that the ®eld of the political is constitutively not singular. I begin, then, with the story of a literary debate. NATIONALISM AS WAYS OF SEEING It does not take much effort to see that a photographic realism or a dedi- cated naturalism could never answer all the needs of vision that modern nationalisms create. -

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02

Code Date Description Channel TV001 30-07-2017 & JARA HATKE STAR Pravah TV002 07-05-2015 10 ML LOVE STAR Gold HD TV003 05-02-2018 108 TEERTH YATRA Sony Wah TV004 07-05-2017 1234 Zee Talkies HD TV005 18-06-2017 13 NO TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla HD TV006 27-09-2015 13 NUMBER TARACHAND LANE Zee Bangla Cinema TV007 25-08-2016 2012 RETURNS Zee Action TV008 02-07-2015 22 SE SHRAVAN Jalsha Movies TV009 04-04-2017 22 SE SRABON Jalsha Movies HD TV010 24-09-2016 27 DOWN Zee Classic TV011 26-12-2018 27 MAVALLI CIRCLE Star Suvarna Plus TV012 28-08-2016 3 AM THE HOUR OF THE DEAD Zee Cinema HD TV013 04-01-2016 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIKA Zee Talkies TV014 22-06-2017 3 BAYAKA FAJITI AIYKA Zee Talkies TV015 21-02-2016 3 GUTTU ONDHU SULLU ONDHU Star Suvarna TV016 12-05-2017 3 GUTTU ONDU SULLU ONDU NIJA Star Suvarna Plus TV017 26-08-2017 31ST OCTOBER STAR Gold Select HD TV018 25-07-2015 3G Sony MIX TV019 01-04-2016 3NE CLASS MANJA B COM BHAGYA Star Suvarna TV020 03-12-2015 4 STUDENTS STAR Vijay TV021 04-08-2018 400 Star Suvarna Plus TV022 05-11-2015 5 IDIOTS Star Suvarna Plus TV023 27-02-2017 50 LAKH Sony Wah TV024 13-03-2017 6 CANDLES Zee Tamil TV025 02-01-2016 6 MELUGUVATHIGAL Zee Tamil TV026 05-12-2016 6 TA NAGAD Jalsha Movies TV027 10-01-2016 6-5=2 Star Suvarna TV028 27-08-2015 7 O CLOCK Zee Kannada TV029 02-03-2016 7 SAAL BAAD Sony Pal TV030 01-04-2017 73 SHAANTHI NIVAASA Zee Kannada TV031 04-01-2016 73 SHANTI NIVASA Zee Kannada TV032 09-06-2018 8 THOTAKKAL STAR Gold HD TV033 28-01-2016 9 MAHINE 9 DIWAS Zee Talkies TV034 10-02-2018 A Zee Kannada TV035 20-08-2017 -

The C Om Poser

The Newsletter | No.65 | Autumn 2013 10 | The Study Rabindrasangit: uncovering a ‘Bengali secret’ The Composer On 14 November 1913, Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for Gitanjali – a selection of his Bengali lyrics in English prose, translated by the poet himself, with an ecstatic introduction by W.B. Yeats. Rabindranath was the first Asian to win the prize, and was honoured that year by bypassing one of the English greats: novelist and poet Thomas Hardy. Rituparna Roy Gitanjali and the Nobel Tagore’s prophecy great memory with a song. If the person grew up in a house When Alfred Nobel instituted the prize in 1901, he intended One of his earliest English admirers and biographer, that cultivated Tagore, then the association will be deeper for the committee to discover a new genius for the world E. P. Thompson, in trying to establish Tagore’s impressive and more vital – but even otherwise, there is no getting away every year. But by 1913, Tagore was already a very distinguished fecundity, wrote in 1948: from Tagore. Especially his songs. My own earliest memory figure in his own country – he was the foremost poet and is of my mother singing Rabindrasangit, late into the evening. writer of Bengal; a pioneering educationist who had started Milton’s English verse is less than 18,000 lines. Tagore’s A marble bust of Tagore had pride of place in our living room an experimental educational institution in Shantiniketan; published verse and dramas amount to 15,000 lines or their – it still does! – the only god that my atheist father has lived and a national leader who had given creative leadership in equivalent. -

Tagore Studies

TAGORE STUDIES PREAMBLE Tagore Studies will be a mainly Activity, Presentation and Seminar-based Learner-Centric Course that will offer the option of taking it up as a Minor Discipline (all six courses for 18 Credits) or One-at-a-time Course (3 Credits) under Open Elective Choice where the participants would be able to engage themselves in Making a Choice, as to which Course/Courses to opt for (for instance, someone from Fine Arts and Aesthetics background may like to opt for ‗Tagore as a Culture Icon with special reference to his Painting‘ or ‗Tagore and Mass Media,‘ whereas a Literature candidate may like to go for ‗Tagore as a Poet‘ and ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Students enrolled in Mass Media and Communication may love to get connected to ‗Tagore and Mass Media‘ as well as ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Those from the History orientation may like to opt for the ‗Cultural History‘ area under ‗Tagore as a Cultural Icon‘ module). Collaboration within or across disciplines to create a joint appraisal/critique/text which could then be presented before the class for internal evaluation – by the faculty and remaining students together – in a peer review mode together.) Communication would be tested on the oral or ppt presentations that a participant may like to make on any aspect of Tagore in a Colloquium model where one person communicates and the others on the panel comment, agree, differ or substantiate etc where their performance is evaluated. Critical thinking with respect to the issues raised by Tagore in the areas on Religion, Societal Practices, Nation Building, or Politics (especially in ENG2652) on which a participant may like to write an end-semester Term Paper. -

09 Nussbaum SYMP

Teaching Patriotism: Love and Critical Freedom Martha C. Nussbaum † Hail the flag of America on land or on sea, Hail the Revolutionary war which made us free. The British proceeded into the hills of Danbury, But soon their army was as small as a cranberry. Remember the brave soldiers who toiled and fought; Bravery is a lesson to be taught. —Martha Louise Craven 1 I. THE JANUS -FACED NATURE OF PATRIOTISM In 1892, a World’s Fair, called the “Columbian Exposition,”2 was scheduled to take place in Chicago. Clearly it was gearing up to be a celebration of unfettered greed and egoism. Industry and innovation † Ernst Freund Distinguished Service Professor of Law and Ethics, University of Chicago. For a symposium on Understanding Education in the United States, University of Chicago Law School, June 17–18, 2011. This paper recasts a chapter in my book Political Emotions (under contract to Harvard University Press), and so I am indebted to all those who have commented on that manuscript, who are too numerous to list here. I am grateful to Jonathan Masur for helpful comments. This paper is an abbreviated version of Teaching Patriotism: Love and Critical Freedom (University of Chicago Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper No 357, July 2011), online at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm ?abstract_id=1898313 (visited Oct 28, 2011). 1 This poem was “written” by me at age six and a half, according to its label and date; it was typed up by my mother (I recognize her paper and font), and I found it in her family album. -

List of National Ngos Upto August-2020

List of National NGOs Upto August-2020 Sl.no Name of NGOs Address Reg. No. Reg. Date Renewed Valid upto District Country Remarks on 1 A Shelter for Helpless Ill House-52, Road-3/A, 1067 26-Aug-96 26-Aug-16 26-Aug-21 Dhaka Bangladesh Children (ASHIC) Dhanmondi, R/A, Dhaka Phone :9673982 www.ashic.org 2 A.B. Foundation Vill., Post + Upazilla: 2024 05-Apr-05 05-Apr-15 05-Apr-20 Dinajpur Bangladesh Chirirbandar, Dist: Dinajpur Phone: 01711-530611 3 A.M. Foster Care House-38, Road-04, Sector--05, 2397 22-Dec-08 22-Dec-13 22-Dec-18 Dhaka Bangladesh Uttara Model Town, Dhaka- 1230. Phone: 01715-475282 4 Abalamban Pachimpara, Post: Gaibandha, 2326 27-Mar-08 27-Mar-18 27-Mar-28 Gaibandha Bangladesh Upazilla: Gaibandha Sadar, Dist.: Gaibandha. Phone: 0541-62388 5 Abdul Halim Khan 1257, Khorompatty, 3123 19-Dec-17 19-Dec-27 Kishorganj Bangladesh Foundation Post+Upazila: Sadar, Kishoreganj, Tel: 01711681660 6 Abdul Momen Khan 5 Momenbagh, Dhaka-1217 0780 04-Dec-93 04-Dec-18 04-Dec-28 Dhaka Bangladesh Memorial Foundation (Khan Phone : 9330323 Foundation) 7 Abdur Rashid Khan Thakur Chapailghat Road, UZ+Zila: 2229 05-Aug-07 08-May-17 08-May-27 Gopalganj Bangladesh Foundation gopalganj-8100 Phone: 8034489, 01911-352919 www.arktf.org 8 Abed Satter Pathen 118 Isdair, Fatullah, 2842 03-Dec-13 03-Dec-18 03-Dec-28 Narayanganj Bangladesh Foundation Narayanganj Phone: 0190-251515 9 Abeda Mannan Foundation Vill: Chulash, Post Office: 2582 15-Jun-10 15-Jun-15 15-Jun-20 Dhaka Bangladesh (AMF) Maricha, Upazilla: Debidwar, Dist: Comilla.