The Welfarist Prime Minister: Explaining the National- State Election Gap

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dalit Factor in Bihar's Politics

7. The (Maha) Dalit Factor in Bihar’s Politics Shreyas Sardesai* Until the 2010 election for the Bihar Assembly, elections in the state were largely analysed in terms of a six caste categories – Upper castes, Yadavs, other OBCs, Pasis, other Dalits and Muslims. Since 2007 however, Bihar politics has witnessed new developments and the caste dimension of elections cannot be fully understood without taking into account two additional caste categories, namely EBCs or Extremely Backward Classes, and Mahadalits. This chapter seeks to analyse the emergence of latter and its implications. In August 2007, the Nitish Kumar led JDU-BJP government set up the Bihar State Mahadalit Commission to “identify the castes within Scheduled Castes who lagged behind in the development process” and to “study [their] educational and social status and suggest measures for [their] upliftment”. In April 2008, 18 Dalit castes were brought under the Mahadalit category to begin with. These are Bantar, Bauri, Bhogta, Bhuiya, Chaupal, Dabgar, Dom/Dhangad, Ghasi, Halalkhor, Hari/Mehtar/Bhangi, Kanjar, Kurariar, Lalbegi, Musahar, Nat, Pan/Swasi, Rajwar and Turi. Three months later Dhobi and Pasi castes were also added to the Mahadalit category based on the Commission’s recommendation and then Chamars were also included in the Mahadalit category by the state government in November 2009 on the grounds that they too were lagging in literacy and economic status and were victims of untouchability at the hands of other Mahadalit castes1. The only sub-caste that was left out was Paswan or Dusadh *Author is Research Associate at Lokniti, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies. -

Leaders @ G-23

www.fi rstindia.co.in OUR EDITIONS: www.fi rstindia.co.in/epaper/ JAIPUR, AHMEDABAD twitter.com/thefi rstindia & LUCKNOW facebook.com/thefi rstindia instagram.com/thefi rstindia LUCKNOW l SUNDAY, FEBRUARY 28, 2021 l Pages 12 l 3.00 RNI NO. UPENG/2020/04393 l Vol 1 l Issue No. 106 HOPE & BEYOND! These Bar Headed Goose fl ying above Chandlai Lake of Jaipur, remind us of the famous American thriller, The Birds, directed by Alfred Hitchcock! Though the movie spoke a lot about the helplessness, in the face of the inevitable, however, this mesmerising photo by First India’s Photojournalist Suman Sarkar, depicts hope for a better future for all as after almost one year of fi ghting the pandemic, the world has got vaccine to fi ght Covid 19. PM: India can ‘CM GEHLOT’S RAHUL IN TN: BUDGET IS A take world WELFARE BUDGET’ Cong has weakened in last back to eco- CHINESE KNOW friendly toys PM IS ‘SCARED’ decade: Leaders @ G-23 New Delhi: Prime Min- ister Narendra Modi on POLL READY: RaGa attacks Modi over Sino- Kapil Sibal said he & other leaders have gathered to address issues that party Saturday said that the India standoff during his 3-day Tamil Nadu tour is facing now; says party didn’t utilise Ghulam Nabi Azad’s experience ancient toy culture of the country reflects the Editor-In-Chief of Jammu: Senior Con- practice of reuse and First India, Jagdeesh gress leaders Kapil recycling, which is part Chandra, in The New Sibal and Anand Shar- of the Indian lifestyle, JC Show, speaks ma on Saturday stated and added that India about how CM Gehlot that the G-23 or the has the potential to take has emerged as a group of 23 dissenting the world back to eco- hero on national leaders are seeing the friendly toys. -

4YRT\` [`Z D 4` X Vi`Ufd

& ' /&! #* #* * SIDISrtVUU@IB!&!!"&#S@B9IV69P99I !%! %! ' %'(%)#*+, (#))(* -(%./ #(%$+, 5 &','&), .3:)$3,.(!$7',",(') 8.7'&.3,.&,5 !'()(.+, %,$(%.%$'3$" ,53'.($")39 $9),3('$-.' "$)"$)." $!)-$" 3.'33),",'33,5!$($)($9$ !'"$!. 6!'"$%$!7)8$6$!$ ( !"#$ %%& 01 2$ 3 ' $ - ##-./.#0#.. R **"% + '!'()*+,) leaders for an organisational , overhaul of the party, Chacko, n a major blow to the who once headed the Joint ICongress in poll-bound Parliamentary Committee on +,) Kerala, senior leader PC 2G Spectrum during the sec- Chacko on Wednesday ond UPA rule, has alleged he ruling CPI(M) on '!'() resigned from the party alleg- party leadership has been TWednesday announced ing group interest in deciding defunct for the last couple of names of 83 candidates it is arliament on Wednesday party candidates for the com- years. He also alleged unde- fielding for the April 6 election Ppassed the National Capital ing Assembly elections. Chacko mocratic ways in selection of to the Kerala Legislative Territory of Delhi Laws (Special also alleged the national lead- candidates for the Kerala Assembly. The party has cho- Provisions) Second ership of the party has not been Assembly polls. sen not to field five Ministers (Amendment) Bill, 2021, to active for the last two years. Referring to the period of in the Pinarayi Vijayan Cabinet regularise unauthorised 2014, but no previous thorised colonies, Puri said He, however, did not vacuum created in the party’s and 33 of its sitting MLAs. the 2024 Lok Sabha election so colonies. Government took this issue up that it is then the Modi announce his future plans but national leadership after Rahul The party which has been that he could be projected as While the Rajya Sabha had with any degree of seriousness. -

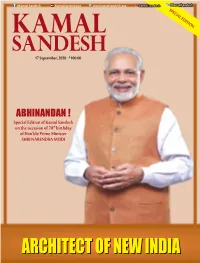

Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha

@Kamal.Sandesh KamalSandeshLive www.kamalsandesh.org kamal.sandesh @KamalSandesh SPECIAL EDITION 17 September, 2020 `100.00 ABHINANDAN ! Special Edition of Kamal Sandesh on the occasion of 70th birthday of Hon’ble Prime Minister SHRI NARENDRA MODI ARCHITECTARCHITECT OFOF NNEWEWArchitect ofII NewNDINDI India KAMAL SANDESHAA 1 Self-reliant India will stand on five Pillars. First Pillar is Economy, an economy that brings Quantum Jump rather than Incremental change. Second Pillar is Infrastructure, an infrastructure that became the identity of modern India. Third Pillar is Our System. A system that is driven by technology which can fulfill the dreams of the 21st century; a system not based on the policy of the past century. Fourth Pillar is Our Demography. Our Vibrant Demography is our strength in the world’s largest democracy, our source of energy for self-reliant India. The fifth pillar is Demand. The cycle of demand & supply chain in our economy is the strength that needs to be harnessed to its full potential. SHRI NARENDRA MODI Hon’ble Prime Minister of India 2 KAMAL SANDESH Architect of New India Fortnightly Magazine Editor Prabhat Jha Executive Editor Dr. Shiv Shakti Bakshi Associate Editors Ram Prasad Tripathy Vikash Anand Creative Editors Vikas Saini Bhola Roy Digital Media Rajeev Kumar Vipul Sharma Subscription & Circulation Satish Kumar E-mail [email protected] [email protected] Phone: 011-23381428, FAX: 011-23387887 Website: www.kamalsandesh.org 04 EDITORIAL 46 2016 - ‘IndIA IS NOT 70 YEARS OLD BUT THIS JOURNEY IS -

Narendra Modi Tops, Yogi Adityanath Enters List

Vol: 23 | No. 4 | April 2017 | R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Hindu-Americans divided on Trump’s immigration policy COVER STORY SOARING HIGH The ties between India and Israel were never better The Pioneer Most Powerful Indians in 2017: Narendra Modi tops,OPINI YogiON EXPR AdityanathESS enters list 1 2 OPINION EXPRESS editorial Modi, Yogi & beyond RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 23, No 4 EDITOR Prashant Tewari – BJP is all set for the ASSOCiate EDITOR Dr Rahul Misra POLITICAL EDITOR second term in 2019 Prakhar Misra he surprise appointment of Yogi Adityanath as Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister post BUREAU CHIEF party’s massive victory in the recently concluded assembly elections indicates that Gopal Chopra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty BJP/RSS are in mission mode for General Election 2019. The new UP CM will (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), T ensure strict saffron legislation, compliance and governance to Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) consolidate Hindutva forces. The eighty seats are vital to BJP’s re- Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj election in the next parliament. PM Narendra Modi is world class Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), leader and he is having no parallel leader to challenge his suprem- Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ) acy in the country. In UP, poor Akhilesh and Rahul were just swept CONTENT partner aside-not by polarization, not by Hindu consolidation but simply by The Pioneer Modi’s far higher voltage personality. Pratham Pravakta However the elections in five states have proved that BJP is not LegaL AdviSORS unbeatable. -

Hon'ble Chief Minister of Bihar-Shri Nitish Kumar

Hon'ble Chief Minister of Bihar-Shri Nitish Kumar Profile: Tel: 2215601, 2217289 Fax- +91-612- 2224129 Email : [email protected] Fathers' Name : Late Kaviraj Ram Lakhan Singh Mother's Name : Late Parmeshwari Devi Date of Birth : 1st March, 1951 Place of Birth : Bakhtiarpur, District - Patna, State - Bihar. Marital Status : Married Date of Marriage : 22nd February, 1973. Spouse's Name : Late Manju Kumari Sinha. No. of Children : One. Educational Qualification : B.Sc. (Engineering) Educated at Bihar College of Engineering, Patna, Bihar. Profession : Political & Social worker, Agriculturist, Engineer. Permanent Address : Village - Hakikatpur , PO - Bakhtiarpur , District -Patna, Bihar Present Address : Patna, Bihar. Positions Held 1985-89 : Member, Bihar Legislative Assembly. 1986-87 : Member, Committee on Petitions, Bihar Legislative Assembly 1987-88 : President, Yuva Lok Dal, Bihar. 1987-89 : Member, Committee on Public Undertakings, Bihar Legislative Assembly 1989 : Secretary - General, Janata Dal, Bihar 1989 : Elected to 9th Lok Sabha. 1989-16/07/1990 : Member, House Committee (Resigned). 04/1990-11/1990 : Union Minister of State, Agriculture and Co-operation. 1991 : Re - elected to 10th Lok Sabha (2nd term). 1991-93 : General - Secretary, Janata Dal, Dy Leader of Janta Dal in Parliament 17/12/91-10/5/96 : Member, Railway Convention Committee. 8/4/93-10/5/96 : Chairman, Committee on Agriculture. 1996 : Re- elected to 11th Lok Sabha (3rd term) Member. Committee on Estimates. Member, General Purposes Committee. Member, Joint Committee on the Constitution (Eighty-first Amendment Bill, 1996). 1996-98 : Member, Committee on Defence. 1998 : Re- elected to 12th Lok Sabha (4th term) 19/3/98-5/8/99 : Union Cabinet Minister, Railways. -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Government of India Ministry of External Affairs Rajya

01/06/2019 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS RAJYA SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO-2568 ANSWERED ON-09.08.2018 Permission for State Ministers to visit China 2568 Shri Ritabrata Banerjee . (a) whether it is a fact that Government is not allowing elected Chief Ministers and other Cabinet Ministers of State Governments to go on a visit to China; (b) if so, the details thereof, State-wise and if not, the reasons therefor; and (c) the details of Chief Ministers and other State Ministers visiting China during the last three years? ANSWER (a) to (c) There are no restrictions on the travel of Chief Ministers and Ministers of State Governments to the People’s Republic of China. On the contrary, under an institutional arrangement between Ministry of External Affairs and the International Department of the Communist Party of China, visits of Chief Ministers of Indian States to China are proactively facilitated in order to promote contacts at the level of provincial leaders and with senior functionaries of the Communist Party of China. Among the Chief Ministers and Ministers of our States, who have visited China since 2015, include: Chief Ministers: S. No. State Minister Period of Visit 1. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu April 2015 2. Gujarat Smt. Anandiben Patel May 2015 3. Maharashtra Shri Devendra Fadnavis May 2015 4. Telangana Shri K. Chandrashekhar Rao September 2015 5. Haryana Shri Manohar Lal Khattar January 2016 6. Chhattisgarh Shri Raman Singh April 2016 7. Andhra Pradesh Shri N. Chandrababu Naidu June 2016 8. Madhya Pradesh Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan June 2016 Ministers of States: S. -

The Hindutva Aspect of COVID-19 Outbreak in India

CENTRE FOR STRATEGIC AND CONTEMPORARY RESEARCH Perspectives Issue No. 11 10 June 2020 The Hindutva Aspect of COVID-19 Outbreak in India Authors: Fahad Nabeel and Maryam Raashed* Key Points: • India’s COVID-19 response outlook is largely characterised by securitisation of the prevailing health crisis, turning it into an Indian Muslims-led conspiracy against the Indian Hindus. • The novel coronavirus has vehemently brought to the fore, how Hindutva forces target Indian minorities, particularly Muslims. • While hate speech against non-Hindus has become a usual practice in India, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has given it a renewed vigour. • A review of trend campaigns by Hindu nationalists and supporters of various Hindutva groups reveals that four themes – propagating Islamophobia, targeting Tablighi Jamaat as the hub of COVID-19, Sinophobic rhetoric and highlighting alleged Hinduphobia in Arab countries - were pursued by these individuals or groups. INTRODUCTION response outlook is largely characterised by securitisation of the prevailing health he outbreak of the COVID-19 crisis, turning it into an Indian Muslims-led pandemic has steered many nation- conspiracy against the Indian Hindus. Hindu states into revamping their traditional nationalists have generated an anti-Muslim security narratives to incorporate a rhetoric through hate speech against Indian Twider spectrum of non-traditional security Muslims. This rhetoric is spreading via threats and the modalities of their response mainstream and social media. The outcome mechanisms. In India however, the role of state of this is rising Islamophobia and hate- is different. The Indian government, led by crimes against Muslims, who are already the Hindutva-inspired Bharatiya Janata Party economically and socially marginalised.2 (BJP), has rather opted to dwell on religious Religious discrimination is not limited to fault lines, thereby exacerbating Hindu 1 Muslims alone. -

India State Chief Ministers

Chief Ministers of India Took office S.No State/UT Name (tenure length) Party Cabinet 1 Andhra Pradesh Y. S. Jaganmohan Reddy 5/30/2019 (1 year, 184 days) YSR Congress Party Jagan I 2 Arunachal Pradesh Pema Khandu 7/17/2016 (4 years, 136 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Khandu II 3 Assam Assam 5/24/2016 (4 years, 190 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Sonowal I 4 Bihar Nitish Kumar 2/22/2015 (5 years, 282 days) Janata Dal (United) Nitish VII 5 Chhattisgarh Bhupesh Baghel 12/17/2018 (1 year, 349 days) Indian National Congress Baghel I 6 Delhi Arvind Kejriwal 2/14/2015 (5 years, 290 days) Aam Aadmi Party Kejriwal III 7 Goa Pramod Sawant 3/19/2019 (1 year, 256 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Sawant I 8 Gujarat Vijay Rupani 7 August 2016 (4 years, 115 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Rupani II 9 Haryana Manohar Lal Khattar 10/26/2014, (6 years, 35 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Khattar II 10 Himachal Pradesh Jai Ram Thakur 12/27/2017, (2 years, 339 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Jai Ram Thakur I 11 Jammu and Kashmir N/A (President's rule) 10/31/2019 (1 year, 30 days) N/A N/A 12 Jharkhand Hemant Soren 12/29/2019 (337 days) Jharkhand Mukti Morcha Soren II 13 Karnataka B. S. Yediyurappa 7/26/2019 (1 year, 127 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Yediyurappa IV 14 Kerala Pinarayi Vijayan 5/25/2016 (4 years, 189 days Communist Party of India (Marxist) Pinarayi I 15 Madhya Pradesh Shivraj Singh Chouhan 3/23/2020 (252 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Shivraj IV 16 Maharashtra Uddhav Thackeray 11/28/2019 (1 year, 2 days) Shiv Sena Thackeray I 17 Manipur N. -

Notification

(TO BE PUBLISHED IN GAZETTE EXTRA ORDINARY, PART 1 – SEC.1) Government of India Ministry of Culture (Special Cell) Notification New Delhi, the 24th September, 2016 F.No. 19-1/2015- Special Cell – To commemorate the Birth Centenary of Pandit Deen Dayal Upadhyaya in a befitting manner, the Competent Authority has approved the constitution of a National Committee. The composition of the National Committee is as under:- NATIONAL COMMITTEE Chairman 1. Shri Narendra Modi, Hon’ble Prime Minister of India Members 2. Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Fr PM, Bharat Ratna 3. Shri H D Deve Gowda, Fr PM of India 4. Smt. Sumitra Mahajan, Speaker of Lok Sabha 5. Shri Rajnath Singh, Home Minister 6. Smt. Sushma Swaraj, External Affairs Minister 7. Shri Arun Jaitley, Finance Minister 8. Shri Manohar Parikkar, Defence Minister 9. Shri Venkaiah Naidu, Urban Development Minister 10. Shri Nitin Gadkari, Minister of Road Transport & Highways & Shipping 11. Shri Suresh Prabhu, Minister of Railways 12. Shri Ram Vilas Paswan, Minister of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution 13. Shri Kalraj Mishra, Minister of MSME 14. Shri Jual Oram, Minister of Tribal Affairs 15. Shri Thaawar Chand Gehlot, Minister of Social Justice and Empowerment 16. Shri Prakash Javadekar, Minister of Human Resource Development 17. Ms Lata Mangeshkar, Bharat Ratna 18. Shri Mahesh Sharma, MoS (IC), Culture 19. Shri Anil Madhav Dave, Environment Minister - MoS (IC) 20. Shri L K Advani, Fr Dy. PM 21. Smt. Mridula Sinha, Governor of Goa 22. Prof. O P Kohli, Governor of Gujarat 23. Prof. Kaptan Singh Solanki, Governor of Haryana 24. Shri Acharya Devvrat, Governor of Himachal Pradesh 25. -

10.05.2021 News in Short Daily Current Affairs

09.05.2021 – 10.05.2021 This CURRENT AFFAIRS bulletin is prepared to help students learn DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS within 10 MINUTES Join in our Daily Current Affairs (DCA) TELEGRAM Channel http://t.me/racedca - For Current Affairs & all the important updates regarding Bank, SSC & Railways Exams. NEWS IN SHORT ① : Himachal Pradesh CM launches ⑥ : Sunder Pichai, Punit Renjen and Shantanu ‘Mukhyamantri Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ Narayen join the global Covid task force ② : Himanta Biswa Sarma sworn-in as 15th Chief ⑦ : Anupam Kher bags best actor award at new Minister of Assam york city international film festival ③ : Madya Pradesh launches new scheme ⑧ : Kalki Koechlin authors her debut book on “Mukhya Mantri Covid Upchar Yojana” motherhood “Elephant In The Womb” ④ : SBI and EIB to invest up to Euro 100 million in ⑨ : Renowned sculptor and Rajya Sabha MP Indian SMEs Raghunath Mohapatra passed away ⑤ : Prime Minister Narendra Modi participates in ⑩ : Lewis Hamilton wins 2021 Spanish Grand Prix India-EU Leaders Summit 2021 DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS – 09.05.2021 – 10.05.2021 NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS • Under this scheme, important decisions have also been taken for free Covid treatment of families Himachal Pradesh CM Jai Ram Thakur launches dedicated possessing Ayushman cards. COVID-19 ‘Mukhyamantri Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ SBI and EIB to invest up to Euro 100 million in Indian SMEs • Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh, Jai Ram Thakur focused on climate change and sustainability launched dedicated COVID-19 Helpline ‘Mukhyamantri • The European Investment Bank (EIB) and State Bank Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ for facilitating the people of India (SBI) entered into a pact to jointly raise Euro regarding COVID related issues in Shimla.