Original Carl Pulfrich and the Role of Instruments to Identify And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Perfect Mix Getting Engaged in College

05 07 10 | reportermag.com GETTING ENGAGED IN COLLEGE The other kind of RIT Rings. THE PERFECT MIX Remember: intro, rising action, climax, denouement and conclusion. ROADTRIP TO THE FUTURE Four men. Four cities. One mission. EDITOR’S NOTE TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 07 10 | VOLUME 59 | ISSUE 29 EDITOR IN CHIEF Madeleine Villavicencio | [email protected] My Innovative Mixtape MANAGING EDITOR Emily Mohlmann Every few weeks or so, I abandon the “shuffle play all” function on my MP3 player, turn off Genius on | [email protected] iTunes, and make a playlist. I spend hours listening to track after track, trimming down the set list and COPY EDITOR Laura Mandanas attempting to get the transitions just right. Sometimes, it just comes together; other times, I just can’t | [email protected] quite get it right. But one thing’s for certain: each mix is a reflection of who I am at the time of its creation. NEWS EDITOR Emily Bogle And if it’s good enough and means something, I’ll share it with someone special. | [email protected] LEISURE EDITOR Alex Rogala It crossed my mind to share a complete and perfected mix, but I decided that would take away from its | [email protected] original value. Instead, I’ve decided to share something unfinished and challenge you to help me find the FEATURES EDITOR John Howard perfect mix. Add or cut tracks as you please, and jumble them up as you see fit. And when you think you’ve | [email protected] got it, send that final track list my way. -

Virtual Reality and Visual Perception by Jared Bendis

Virtual Reality and Visual Perception by Jared Bendis Introduction Goldstein (2002) defines perception as a “conscious sensory experience” (p. 6) and as scientists investigate how the human perceptual system works they also find themselves investigating how the human perceptual system doesn’t work and how that system can be fooled, exploited, and even circumvented. The pioneers in the ability to control the human perceptual system have been in the field of Virtual Realty. In Simulated and Virtual Realities – Elements of Perception, Carr (1995) defines Virtual Reality as “…the stimulation of human perceptual experience to create an impression of something which is not really there” (p. 5). Heilig (2001) refers to this form of “realism” as “experience” and in his 1955 article about “The Cinema of the Future” where he addresses the need to look carefully at perception and breaks down the precedence of perceptual attention as: Sight 70% Hearing 20% Smell 5% Touch 4% Taste 1% (p. 247) Not surprisingly sight is considered the most important of the senses as Leonardo da Vinci observed: “They eye deludes itself less than any of the other senses, because it sees by none other than the straight lines which compose a pyramid, the base of which is the object, and the lines conduct the object to the eye… But the ear is strongly subject to delusions about the location and distance of its objects because the images [of sound] do not reach it in straight lines, like those of the eye, but by tortuous and reflexive lines. … The sense of smells is even less able to locate the source of an odour. -

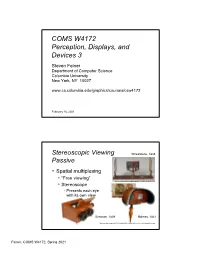

COMS W4172 Perception, Displays, and Devices 3

COMS W4172 Perception, Displays, and Devices 3 Steven Feiner Department of Computer Science Columbia University New York, NY 10027 www.cs.columbia.edu/graphics/courses/csw4172 February 16, 2021 1 Stereoscopic Viewing Wheatstone, 1838 Passive . Spatial multiplexing . “Free viewing” http://www.luminous-lint.com/app/image/06751152706639519425853376/ . Stereoscope . Presents each eye with its own view Brewster, 1839 Holmes, 1861 http://www.gilai.com/product_763/Holms-Wood-Stereoscope-with-Green-Velvet-Lining-and-Stereocard. 2 Feiner, COMS W4172, Spring 2021 Stereoscopic Viewing Passive . Spatial multiplexing . “Free viewing” . Stereoscope presents each eye with its own view 3 What’s wrong with these pictures? 4 Feiner, COMS W4172, Spring 2021 Commercial versions (w/o camera support): • www.amazon.com/Hasbro-Viewer-touch- Stereoscopic Viewing iPhone-Black/dp/B004T7VI2Y • www.samsung.com/global/galaxy/gear-vr For commodity • arvr.google.com/cardboard • arvr.google.com/daydream/smartphonevr Passive mobile devices • holokit.io/ (optical see-through) . Spatial multiplexing . VR: Stereoscopic viewer for smartphone/tablet . AR: 1. Cheat: Separate left/right stereoscopic views of virtual objects combined with L–R shifted copies of a monoscopic camera view 2. Full video see-through stereo using additional camera lens (e.g., www.kula3d.com/kula-bebe) Stereo viewer used with Columbia’s Goblin XNA and Nokia Lumia 800 3. Optical see-through stereo using 2012 additional optics (e.g., holokit.io) Google Cardboard, 2014 https://arvr.google.com/cardboard/ Stereo viewer for Nokia Lumia 800 courtesy of USC ICT MxR Lab, 2012 https://web.archive.org/web/20190314093037/http://projects.ict.usc.edu/mxr/diy/fov2go-viewer/ 5 Autostereoscopic Viewing Passive . -

Course Notes

Siggraph ‘97 Stereo Computer Graphics for Virtual Reality Course Notes Lou Harrison David McAllister Martin Dulberg Multimedia Lab Department of Computer Science North Carolina State University ACM SIGGRAPH '97 Stereoscopic Computer Graphics for Virtual Reality David McAllister Lou Harrison Martin Dulberg MULTIMEDIA LAB COMPUTER SCIENCE DEPARTMENT NORTH CAROLINA STATE UNIVERSITY http://www.multimedia.ncsu.edu Multimedia Lab @ NC State Welcome & Overview • Introduction to depth perception & stereo graphics terminology • Methods to generate stereoscopic images • Stereo input/output techniques including head mounted displays • Algorithms in stereoscopic computer graphics Multimedia Lab @ NC State Speaker Biographies: David F. McAllister received his BS in mathematics from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 1963. Following service in the military, he attended Purdue University, where he received his MS in mathematics in 1967. He received his Ph. D. in Computer Science in 1972 from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. McAllister is a professor in the Department of Computer Science at North Carolina State University. He has published many papers in the areas of 3D technology and computer graphics and has given several courses in these areas at SPIE, SPSE, Visualization and SIGGRAPH. He is the editor of a book on Stereo Computer Graphics published by Princeton University Press. Lou Harrison received his BS in Computer Science from North Carolina State University in 1987 and his MS in Computer Science, also from NCSU, in 1990. Mr. Harrison has taught courses in Operating Systems and Computer Graphics at NCSU and is currently Manager of Operations for the Department of Computer Science at NCSU while pursuing his Ph. -

3D Display Techniques for Cartographic Purposes: Semiotic Aspects

Buchroithner, Manfred 3D DISPLAY TECHNIQUES FOR CARTOGRAPHIC PURPOSES: SEMIOTIC ASPECTS Manfred F. Buchroithner*, Robert Schenkel**, Sabine Kirschenbauer*** Dresden University of Technology, Germany Institute of Cartography *[email protected], **[email protected], ***[email protected] KEY WORDS: 3D-Display Techniques, Cartographic Semiotic, Psychological Cues, Cognition ABSTRACT The variety of the cartographic 3D-visualisation is constantly increasing and thereby more and more fields of application are being developed. These facts require that the coherence of technical, perceptive-psychological and cartographic-theoretical aspects has to be subdivided and classified. Through these formulations of interdependence of the single parameters shall be pointed out. The consideration of communication-theoretical and perceptive-theoretical aspects shall lead to a purpose-oriented realisation of the 3D-visualisation techniques according to the user’s necessities. KURZFASSUNG Das thematische Gebiet “Kartographische 3D-Visualisierung”, dessen Vielfältigkeit ständig zunimmt und dem immer mehr Anwendungsbereiche erschlossen werden, erfordert, daß die Zusammenhänge von technisch- verfahrensspezifischen, wahrnehmungspsychologischen und kartographisch-theoretischen Faktoren aufgeschlüsselt und klassifiziert werden. Hierdurch sollen Ansätze einer Interdependanz der einzelnen Parameter aufgezeigt werden. Die Berücksichtigung kommunikationstheoretischer und wahrnehmungstheoretischer Aspekte soll zu einer anwendergerechten -

3D Frequently Asked Questions

3D Frequently Asked Questions Compiled from the 3-D mailing list 3D Frequently Asked Questions This document was compiled from postings on the 3D electronic mail group by: Joel Alpers For additions and corrections, please contact me at: [email protected] This is Revision 1.1, January 5, 1995 The information in this document is provided free of charge. You may freely distribute this document to anyone you desire provided that it is passed on unaltered with this notice intact, and that it be provided free of charge. You may charge a reasonable fee for duplication and postage. This information is deemed accurate but is not guaranteed. 2 Table Of Contents 1 Introduction . 7 1.1 The 3D mailing list . 7 1.2 3D Basics . 7 2 Useful References . 7 3 3D Time Line . 8 4 Suppliers . 9 5 Processing / Mounting . 9 6 3D film formats . 9 7 Viewing Stereo Pairs . 11 7.1 Free Viewing - viewing stereo pairs without special equipment . 11 7.1.1 Parallel viewing . 11 7.1.2 Cross-eyed viewing . 11 7.1.3 Sample 3D images . 11 7.2 Viewing using 3D viewers . 11 7.2.1 Print viewers - no longer manufactured, available used . 11 7.2.2 Print viewers - currently manufactured . 12 7.2.3 Slide viewers - no longer manufactured, available used . 12 7.2.4 Slide viewers - currently manufactured . 12 8 Stereo Cameras . 13 8.1 Currently Manufactured . 13 8.2 Available used . 13 8.3 Custom Cameras . 13 8.4 Other Techniques . 19 8.4.1 Twin Camera . 19 8.4.2 Slide Bar . -

3D Television - Wikipedia

3D television - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3D_television From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 3D television (3DTV) is television that conveys depth perception to the viewer by employing techniques such as stereoscopic display, multi-view display, 2D-plus-depth, or any other form of 3D display. Most modern 3D television sets use an active shutter 3D system or a polarized 3D system, and some are autostereoscopic without the need of glasses. According to DisplaySearch, 3D televisions shipments totaled 41.45 million units in 2012, compared with 24.14 in 2011 and 2.26 in 2010.[1] As of late 2013, the number of 3D TV viewers An example of three-dimensional television. started to decline.[2][3][4][5][6] 1 History 2 Technologies 2.1 Displaying technologies 2.2 Producing technologies 2.3 3D production 3TV sets 3.1 3D-ready TV sets 3.2 Full 3D TV sets 4 Standardization efforts 4.1 DVB 3D-TV standard 5 Broadcasts 5.1 3D Channels 5.2 List of 3D Channels 5.3 3D episodes and shows 5.3.1 1980s 5.3.2 1990s 5.3.3 2000s 5.3.4 2010s 6 World record 7 Health effects 8See also 9 References 10 Further reading The stereoscope was first invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1838.[7][8] It showed that when two pictures 1 z 17 21. 11. 2016 22:13 3D television - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/3D_television are viewed stereoscopically, they are combined by the brain to produce 3D depth perception. The stereoscope was improved by Louis Jules Duboscq, and a famous picture of Queen Victoria was displayed at The Great Exhibition in 1851. -

Anaglyph Image - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Anaglyph image - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anaglyph_image Anaglyph image From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia 1 of 11 12/28/08 6:41 PM Anaglyph image - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anaglyph_image Stereo monochrome image anaglyphed for red (left eye) and cyan (right eye) filters. Stereogram source image for the anaglyph above. Stereoscopic effect used in Macro photography. 2 of 11 12/28/08 6:41 PM Anaglyph image - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anaglyph_image Anaglyph images are used to provide a stereoscopic 3D effect, when viewed with 2 color glasses (each lens a chromatically opposite color, usually red and cyan). Images are made up of two color layers, superimposed, but offset with respect to each other to produce a depth effect. Usually the main subject is in the center, while the foreground and background are shifted laterally in opposite directions. The picture contains two differently filtered colored images, one for each eye. When viewed through the "color coded" "anaglyph glasses", they reveal an integrated stereoscopic image. The visual cortex of the brain fuses this into perception of a Anaglyph (3D photograph) of three dimensional scene or composition. Saguaro National Park at dusk. Anaglyph images have seen a recent resurgence due to the presentation of images and video on the internet, Blu-ray HD disks, CDs, and even in print. Low cost paper frames or plastic-framed glasses hold accurate color filters, that typically, after 2002 make use of all 3 primary colors. The current norm is red for one channel (usually the left) and a combination of both blue and green in the other filter. -

PROCESSES in BIOLOGICAL VISION: Including

PROCESSES IN BIOLOGICAL VISION: including, ELECTROCHEMISTRY OF THE NEURON This material is excerpted from the full β-version of the text. The final printed version will be more concise due to further editing and economical constraints. A Table of Contents and an index are located at the end of this paper. James T. Fulton Vision Concepts [email protected] April 30, 2017 Copyright 2004 James T. Fulton Dynamics of Vision 7- 1 7 Dynamics of Vision 1 The dynamics of the visual process have not been assembled and presented in a cogent manner within the academic vision literature. On the other hand, several authors have presented cogent descriptions applicable to the clinical level. The material assembled by Salmon at Northeastern State University2 in Oklahoma is exemplary (but superficial for the purpose at hand). The dynamics associated with the mechanism of interpreting symbols and character groups, called reading, has not been presented at all. Only the major eye movements related to reading have been studied in significant detail. Even the adaptation characteristic of vision as a function of illumination level has not been presented from a theoretical perspective, and the empirical data has not been analyzed in sufficient detail to provide a coherent understanding of the process. When assembled as a group, the mechanisms and processes associated with forming the chromophores of vision provide a new, interesting and unique perspective on the formation of those chromophores. This Chapter will assemble the pertinent data with respect to a variety of processes where their dynamic aspects are crucial to the visual function. 7.1 Characteristics & Dynamics of Retinoids in the body The following material is based on extensive empirical investigations that were largely lacking with regard to any contiguous theory of what the goals of the mechanisms involved were from the perspective of the visual modality. -

Visual Perception

Overview Vision & Visuals Human Visual Systems Visual Perceptions 3D Depth Cues 3D Stereographics Terminology Stereo Approximation 3D Displays & Auto-Stereoscopic Displays 029515 Desiggpyn Issues for VR Visual Displays 2010년 봄학기 3/29/2010 박경신 Human Visual System Human Eyes Light is focused by the cornea and the lens onto the retina Light passing through the center of the cornea and thlhe lens hi hihfts the fovea (or Macu l)la) Iris permits the eye to adapt to varying light levels, contro lling the amoun t o f lig ht en ter ing the eye. Retina is optically receptive layer like a film in a camera Retina translate light into nerve signals. Retina has photoreceptors (rods & cones) and inter- neurons. Photoreceptors (Rods & Cones) Rods & Cones Distribution Rods Rods & Cones Distribution Operate at lower illumination levels Fovea Luminance-only only cone receptors with The most sensitive to light very hihigh h dens itity At night where the cones cannot detect the light, the rods provide us with a black and white view of the world no rods The rods are also more sensitive to the blue end of the no S-cones (blue cones) spectrum responsible for high visual Cones acuity operate at higher illumination levels Blind Spot provide better spatial resolution and contrast sensitivity no receptors provide color vision (currently believed there are 3 types of Axons o f a ll gangli lion ce lls cones in human eye, one attuned to red, one to green and pass through the blind spot one to blue) [Young-Helmholtz Theory] on the way to the brain provide visual acuity Visual Spectrum Color Perception We perceive electromagnetic There are three types of energy having wavelengths cones, referred to as S, M, in the range 400 nm ~ 700 and L. -

WO 2013/158322 Al 24 October 2013 (24.10.2013) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2013/158322 Al 24 October 2013 (24.10.2013) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (74) Agent: STEIN, Michael, D.; Woodcock Washburn LLP, G06T 15/08 (201 1.01) Cira Centre, 2929 Arch Street, 12th Floor, Philadelphia, PA 19104-2891 (US). (21) International Application Number: PCT/US20 13/032821 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, (22) Date: International Filing AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, 18 March 2013 (18.03.2013) BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, (25) Filing Language: English DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (26) Publication Language: English KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (30) Priority Data: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 61/635,075 18 April 2012 (18.04.2012) US NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (71) Applicant: THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, OF CALIFORNIA [US/US]; 1111 Franklin Street, ZM, ZW. Twelfth Floor, Oakland, CA 94607 (US). (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (72) Inventors: DAVIS, James E.; 1156 High Street: SOE3, kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, Santa Cruz, CA 95064 (US). -

The Stroboscopic Pulfrich Effect Is Not Evidence for the Joint Encoding of Motion and Depth

Journal of Vision (2005) 5, 417-434 http://journalofvision.org/5/5/3/ 417 The stroboscopic Pulfrich effect is not evidence for the joint encoding of motion and depth Laboratory of Sensorimotor Research, National Eye Institute, Jenny C. A. Read National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD Laboratory of Sensorimotor Research, National Eye Institute, Bruce G. Cumming National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD In the Pulfrich effect, an illusion of depth is produced by introducing differences in the times at which a moving object is presented to the two eyes. In the classic form of the illusion, there is a simple explanation for the depth percept: the interocular delay introduces a spatial disparity into the stimulus. However, when the moving object is viewed stroboscopically, this simple explanation no longer holds. In recent years, depth perception in the stroboscopic Pulfrich effect has been explained by invoking neurons that are sensitive both to stereo disparity and to direction of motion. With such joint motion/disparity encoders, interocular delay causes a perception of depth by causing a shift in each neuron’s preferred disparity. This model has been implemented by N. Qian and R. A. Andersen (1997). Here we show that this model's predictions for perceived disparity are quantitatively at odds with psychophysical measures. The joint-encoding model predicts that the perceived disparity is the virtual disparity implied by the apparent motion; in fact, the perceived disparity is smaller. We show that the percept can be quantitatively explained on the basis of spatial disparities present in the stimulus, which could be extracted from pure disparity sensors.