A Comparison Study of International Terrorism Using Geographic Information Systems Michael Alaimo & Yonghong Tong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of the Terrorism on North African Tourism

The impact of the terrorism on North African tourism Florentina-Stefania NEAGU The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Bucharest, Romania [email protected] Abstract. Tourism is one of the most important sector of the national economy and in the same time is the main reason for which the tourists visit the North African states. In 2015, the total contribution of North African tourism represent 10.8% from GDP registering an increase of 1.4% compared to 2014, also the contribution of tourism to employment was 10.4 % in 2015. But this increase was affected by the terrorist attacks in Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia. According to Global Terrorism Index for 2016, these countries are in the ranking of states with the highest impact of terrorism. Security situation in 2015 is the following: 947 incidents, 1198 deaths, 1603 injured, 264 property damages. This situation greatly influences the decision of tourists to travel in these countries. For demonstrate what is the impact on terrorism in this region have been analized the data bases of World Travel and Tourism Council, Council and Foreign Relations and Global Terrorism Database for the period 2010-2015. If the terrorist attacks continue in the next years not only the tourism will be affected but also the activities of its associates. Keywords: tourism, tourists, terrorism, security. Introduction The tourism industry annually attracts millions of tourists who want to discover new places, have fun and practice sports. The purpose of tourism is to satisfy the needs of tourists by providing them comfortable accommodation, food of the highest quality and providing entertainment. -

Senegal Summary 2020

Senegal - Threat Assessment - 2020 Page 1 of 10 Modern Slavery: The 2018 GSI Index: 46/51 1. Senegal African countries, with 43,000 modern day slaves, and an incidence of 2.9/1000 people, Section 1 - Executive Summary and a “B” response. US Trafficking in Persons gave Senegal a Tier 2 rating. Grey Lists: Senegal is not listed by FATF, or by the EU on their “Grey” lists. Senegal is, Sanctions & Terrorism: There are no sanctions however, listed by the US as a “Country of against the country. Senegal is a Tier 3 (lowest Primary Concern” in respect of ML & FC. threat) PPI 2019 (Proliferation) Index country with a “moderate ” control score of 370/1,300. National Risk Assessment: Senegal Senegal has a “very low” impact (score completed a National Risk Assessment, though 1.186/10) in the 2019 Global Terrorism Index. it appears not to be publicly available. Senegal is in US Country Reports on Terrorism. According to the GIABA report in 2018, the “NRA identified the most prevalent predicate Response & Resilience: FATF MER 4th round offences of money laundering which are: fraud, results by GIABA in 2018, were 43/100 for drug trafficking, migrants smuggling, “Technical Compliance” 40 Recommendations corruption, customs and tax offences,” and & 3/100 for “Effectiveness” 11 Outcomes. “high risk sectors are: money transfer; Senegal scored 6.04/10 for resilience (high), authorised foreign exchange; electronic ranked 5/54 for Africa in the OC Index. money; the hotel sector; the real estate sector; the legal and accounting professions.” Indices: Senegal scored 71/100, and rated “partly free” in the 2019 Freedom in the World Organised Crime: According to the OC Index, Index, and 58/100 for economic freedom Low Criminality - High Resilience. -

Global Peace Index 2018: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2018

Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City and Brussels. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Peace Index 2018: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2018. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings 4 RESULTS 5 Highlights 6 2018 Global Peace Index rankings 8 Regional overview 12 Improvements & deteriorations 19 TRENDS 23 Ten year trends in the Global Peace Index 26 100 year trends in peace 32 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF VIOLENCE 45 Results 46 The macroeconomic impact of peace 52 POSITIVE PEACE 59 What is Positive Peace? 60 Trends in Positive Peace 65 What precedes a change in peacefulness? 69 Positive Peace and the economy 73 APPENDICES 77 Appendix A: GPI Methodology 78 Appendix B: GPI indicator sources, definitions & scoring criteria 82 Appendix C: GPI Domain scores 90 Appendix D: Economic cost of violence 93 GLOBAL PEACE INDEX 2018 | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the twelfth edition of the Global Peace Index Afghanistan, South Sudan, Iraq, and Somalia comprise (GPI), which ranks 163 independent states and the remaining least peaceful countries. -

Role of Environment and Environmental Education on Global Peace- an Analytical Study

International Journal of Scientific Research and Review ISSN NO: 2279-543X Role of Environment and Environmental Education on Global Peace- An Analytical Study Dr. Surajit Let, Assistant Professor, Dept. of Geography Krishna Chandra College, (Hetampur, Birbhum) [email protected] Abstract: Peace is the mental state of happiness. There are two types of peace Positive peace and Negative peace. When in a place there is no violence such as wars is known as Negative peace on the contrary positive peace refers to the absence of structural violence that is the systematic inequities such as gender or racial discrimination. No doubt, environment is an influencing factor for peace but not a controlling factor. If we able to find out the relationship between environment and peace then it will be easy to judge the role of environmental education on global peace. Actually we should remember that global peace and mental peace is not same things. So in broad sense it is very critical to analyze. To show the relationship between environment and global peace I have used two index Environmental Performance Index (EPI) and Environmental vulnerability Index (EVI) to show the global position of those countries in respect of environmental performance. To show the global position in respect of peace I have used Global Peace Index (GPI). Key- words: Environmental Performance Index, Global Peace Index, Environmental vulnerability Index’ Resource management, global citizen, sustainable society, Global conflict. A. Introduction: Education is a lifelong process, which takes place from the womb to the tomb. Education is a human right. It is the mirror of our modern society and essential for human emancipation and social development (Sharma, 2003). -

Autocracy and Anocracy.*

Autocracy and Anocracy. Norman Scho…eldyand Maria Gallegoz Center in Political Economy, Washington University, 1 Brookings Drive,Saint Louis, MO 63130. September 7, 2011 1 Institutions and Democratization Recent events have focussed the world’s attention on how autocrats have sur- vived for so long in countries like Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, and what triggers popular revolt. The literature on transitions to democracy has been partly historical, building on the seminal work of Douglass North on the role of insti- tutions, and partly empirical and theoretical, using aspects of game theory to model the calculations of autocrats as they …ght to maintain power. In the historical mode, there has been discussions about why North America was able to follow Britain in a path of economic development, but Latin Amer- ica and the Caribbean islands, though generally far richer initially, fell behind in the nineteenth century. In their discussion of Latin American economic de- velopment, Sokolo¤ and Engerman (2000) have emphasized the di¤erent factor endowments of North and South America.1 In addition they have suggested that slavery in the New World resulted in institutions that were not conducive to economic growth.2 In contrast, Przeworski and Curvale (2006) argue that while economic in- equality tended to persist and has been related to the degree of political inequal- ity, many aspects of the developmental path appear highly contingent. Indeed, whether Latin American economies grew, and the extent to which they pro- tected the factors of capital, land and labor, seems to be dependent on shifting This chapter is based on work supported by NSF grant 0715929 and a Weidenbaum Center grant. -

Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES POVERTY, POLITICAL FREEDOM, AND THE ROOTS OF TERRORISM Alberto Abadie Working Paper 10859 http://www.nber.org/papers/w10859 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 October 2004 I thank Alan Krueger, David Laitin, Todd Olmstead, and Richard Zeckhauser for comments and suggestions. Financial support for this research was generously provided through NSF grant SES-0350645. The views expressed herein are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. ©2004 by Alberto Abadie. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Poverty, Political Freedom, and the Roots of Terrorism Alberto Abadie NBER Working Paper No. 1085 October 2004 JEL No. D74, K42, H56 ABSTRACT This article provides an empirical investigation of the determinants of terrorism at the country level. In contrast with the previous literature on this subject, which focuses on transnational terrorism only, I use a new measure of terrorism that encompasses both domestic and transnational terrorism. In line with the results of some recent studies, this article shows that terrorist risk is not significantly higher for poorer countries, once the effects of other country-specific characteristics such as the level of political freedom are taken into account. Political freedom is shown to explain terrorism, but it does so in a non-monotonic way: countries in some intermediate range of political freedom are shown to be more prone to terrorism than countries with high levels of political freedom or countries with highly authoritarian regimes. -

Joshua Meservey Senior Policy Analyst, Africa and the Middle East the Heritage Foundation

Looking Forward: U.S.-Africa Relations Testimony before the Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations House Foreign Affairs Committee United States House of Representatives March 26, 2019 Joshua Meservey Senior Policy Analyst, Africa and the Middle East The Heritage Foundation Chairwoman Bass, Ranking Member Smith, to protect its national interests there. This is and members of the committee, thank you an evergreen challenge that has grown more for this opportunity to testify before you. urgent given the rising great and middle With your permission, I would like to submit power competition in Africa. Many my written testimony into the record. countries are rapidly expanding their engagement on the continent—the U.S. The views I express in this testimony are my should welcome that development in the own and should not be construed as case of its allies, but for aggressive American representing any official position of The competitors such as China and Russia, it is a Heritage Foundation. challenge. U.S. Strategic Priorities in Africa One example of this problem is the port in In this testimony, I will focus on what I Djibouti. Ninety percent of the equipment consider to be the four most important U.S. the U.S. military uses to conduct its strategic priorities in Africa that should operations in East Africa flow through guide American engagement with the Djibouti. 1 Chinese companies now operate continent. three of the five terminals in Djibouti port, whereas in early 2017 they did not operate First, the U.S. must retain sufficient influence and positioning on the continent 1 General Thomas D. -

Global Peace Index Global Peace

GLOBAL PEACE INDEX PEACE GLOBAL GLOBAL PEACE 2019 INDEX 2019 MEASURING PEACE IN A COMPLEX WORLD Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human wellbeing and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity, as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City, Brussels and Harare. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Global Peace Index 2019: Measuring Peace in a Complex World, Sydney, June 2019. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings 4 RESULTS 5 Highlights 6 2019 Global Peace Index Rankings 8 Regional Overview 13 Improvements & Deteriorations 20 TRENDS 25 GPI Trends 26 Peace Perceptions 32 Climate Change and Peace 43 ECONOMIC IMPACT OF VIOLENCE 57 Results 58 Methodoogy at a glance 63 POSITIVE PEACE 65 What is Positive Peace? 66 Positive Peace and Negative Peace 71 Positive Peace and the Economy 76 APPENDICES 83 Appendix A: GPI Methodology 84 Appendix B: GPI indicator sources, definitions & scoring criteria 88 Appendix C: GPI Domain Scores 96 Appendix D: Economic Cost of Violence 99 GLOBAL PEACE INDEX 2019 | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This is the thirteenth edition of the Global Peace Index Four of the nine regions in the world became more (GPI), which ranks 163 independent states and peaceful over the past year. -

“Global Terrorism Index: 2015.” Institute for Economics and Peace

MEASURING AND UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP has offices in Sydney, New York and Mexico City. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organizations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org SPECIAL THANKS to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) headquartered at the University of Maryland for their cooperation on this study and for providing the Institute for Economics and Peace with their Global Terrorism Database (GTD) datasets on terrorism. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ABOUT THE GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX 6 1 RESULTS 9 Global Terrorism Index map 10 Terrorist incidents map 12 Ten countries most impacted by terrorism 20 Terrorism compared to other forms of violence 30 2 TRENDS 33 Changes in the patterns and characteristics of terrorist activity 34 Terrorist group trends 38 Foreign fighters in Iraq -

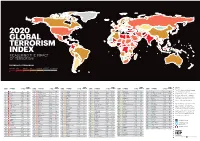

2020 Global Terrorism Index Measuring the Impact of Terrorism

2020 GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX MEASURING THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM VERY HIGH HIGH MEDIUM LOW VERY LOW NO IMPACT NOT INCLUDED 10 8 6 4 2 0 RANK RANK RANK RANK RANK RANK ABOUT RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE RANK COUNTRY SCORE CHANGE The GTI is developed by the Institute 1 Afghanistan 9.592 28 Ethiopia 5.307 56 Canada 3.171 3 84 Malawi 1.635 19 112 Azerbaijan 0.296 10 =135 Cuba 0.000 for Economics & Peace, an United States of 2 Iraq 8.682 29 5.260 2 57 Jordan 3.149 5 85 Denmark 1.484 15 113 Switzerland 0.286 3 =135 Dominican Republic 0.000 44 independent, non-partisan, non-profit America 3 Nigeria 8.314 58 Tanzania 3.112 2 86 Gabon 1.43 18 114 Poland 0.239 9 =135 El Salvador 0.000 30 United Kingdom 5.161 4 think tank dedicated to shifting the 4 Syria 7.778 =59 Belgium 3.043 6 87 Norway 1.297 40 =115 Jamaica 0.229 11 =135 Equatorial Guinea 0.000 31 Palestine 5.077 1 world’s focus to peace as a positive, 5 Somalia 7.645 1 =59 Italy 3.043 3 88 Madagascar 1.19 7 =115 Lithuania 0.229 9 =135 Eritrea 0.000 32 Saudi Arabia 5.000 3 achievable and tangible measure of 6 Yemen 7.581 1 61 Sweden 2.892 5 89 Costa Rica 1.066 74 =115 Sierra Leone 0.229 9 =135 Guinea-Bissau 0.000 33 Bangladesh 4.909 3 human wellbeing and progress. -

2015 Global Terrorism Index Report

MEASURING AND UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TERRORISM Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP has offices in Sydney, New York and Mexico City. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organizations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org SPECIAL THANKS to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), a Department of Homeland Security Center of Excellence led by the University of Maryland, for their cooperation on this study and for providing the Institute for Economics and Peace with their Global Terrorism Database (GTD) datasets on terrorism. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 ABOUT THE GLOBAL TERRORISM INDEX 6 1 RESULTS 9 Global Terrorism Index map 10 Terrorist incidents map 12 Ten countries most impacted by terrorism 20 Terrorism compared to other forms of violence 30 2 TRENDS 33 Changes in the patterns and characteristics of terrorist activity 34 -

Regimes of the World (Row): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes

Politics and Governance (ISSN: 2183–2463) 2018, Volume 6, Issue 1, Pages X–X DOI: 10.17645/pag.v6i1.1214 Article Regimes of the World (RoW): Opening New Avenues for the Comparative Study of Political Regimes Anna Lührmann *, Marcus Tannenberg and Staffan I. Lindberg V-Dem Institute, Department of Political Science, University of Gothenburg, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden; E-Mails: [email protected] (A.L.), [email protected] (M.T.), [email protected] (S.I.L.) * Corresponding author Submitted: 3 October 2017 | Accepted: 12 January 2018 | Published: in press Abstract Classifying political regimes has never been more difficult. Most contemporary regimes hold de-jure multiparty elections with universal suffrage. In some countries, elections ensure that political rulers are—at least somewhat—accountable to the electorate whereas in others they are a mere window dressing exercise for authoritarian politics. Hence, regime types need to be distinguished based on the de-facto implementation of democratic institutions and processes. Using V-Dem data, we propose with Regimes of the World (RoW) such an operationalization of four important regime types—closed and electoral autocracies; electoral and liberal democracies—with vast coverage (almost all countries from 1900 to 2016). We also contribute a solution to a fundamental weakness of extant typologies: The unknown extent of misclassification due to uncertainty from measurement error. V-Dem’s measures of uncertainty (Bayesian highest posterior densities) allow us to be the first to provide a regime typology that distinguishes cases classified with a high degree of certainty from those with “upper” and “lower” bounds in each category.