Bob Marley's Music As an Alternative Communicative Channel In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bob Marley Background Informations

Bob Marley Background informations: Birth name: Robert Nesta Marley Also known as: Tuff Gong Born: February 6, 1945 Nine Miles, Saint Ann, Jamaica Died: May 11, 1981 Genre: Reggae, ska, rocksteady Occupation: Singer, songwriter, guitarist Instrument: Guitar, vocals Years active: 1962 – 1981 Label: Studio One, Beverley’s Upseeter/ Trojan Island/Tuff Gong Associated acts: The wailers Band, The Wailers HITS: . I shot the sheriff, . No woman, No cry, . Three little birds, . Exodus, . Could you be loved, . Jamming, . Redemption song . One love[one of his most famous love songs] Bob Marley once reflected: I don’t have prejudice against myself. My father was white and my mother was black. Them call me half-caste or whatewer. Me don’t dip on nobady’s side. Me don’t dip on the black man’s side or the white man’s side. Me dip on God’s side, the one who create me and cause me to come from black and white. Musical career: Bob Marley, Bunny Livingston, Peter McIntosh, Junior Braitheaite, Beverley Kelso and Cherry Smith – rocksteady group first named “The Teenagers”. Later “The Wailing Rudeboys”, then to “The Wailing Wailers”, and finally to “The Wailers”. Albums: * The Wailing Wailers 1966 * The Best of the Wailers 1970 * Soul Rebels 1970 * Soul Revolution 1971 * Soul Revolution Part II 1971 * African Herbsman 1973 * Catch a Fire 1973 [Wailers first album] * Burnin' 1973 * Rasta Revolution 1974 * Natty Dread 1974 * Rastaman Vibration 1976 * Exodus 1977 * Kaya 1978 * Survival 1979 * Uprising 1980 * Confrontation (izdano po Marleyjevi smrti) 1983 Bob Marley’s 13 childrens: . Imani Carole, born May 22, 1963, to Cheryl Murray; . -

Bob Marley: 40 Anni Fa L'ultimo Concerto Della Star Del Reggae

GIOVEDì 17 SETTEMBRE 2020 Proprio in questi giorni è disponibile in edicola la discografia di BOB MARLEY. In una sola collezione di 17 cd, gli album da studio originali e i migliori concerti live: tra questi, non può ovviamente mancare "Bob Bob Marley: 40 anni fa l'ultimo Marley & The Wailers-Live Forever: The Stanley Theatre, Pittsburgh", concerto della star del reggae edizione ufficiale dell'ultimo storico concerto live del "profeta" del reggae. Esattamente 40 anni fa, infatti, il 23 settembre 1980 - data simbolo per tutti i fan del reggae e non solo - Marley e la sua band, The Wailers, si esibivano con il loro "Uprising Tour" in Pennsylvania, allo Stanley Theater. CRISTIAN PEDRAZZINI Sarebbe stato il suo ultimo concerto, prima della prematura scomparsa (11 maggio 1981). Diventato un eroe per milioni di persone grazie a canzoni che parlano di sofferenza e salvezza, sebbene esausto e già provato dalla malattia, in quella serata memorabile Bob Marley propose una grandiosa e trionfale setlist: successi come Coming in from the Cold, Work, Could You Be [email protected] Loved, la leggendaria Redemption Song e Zion Train (tratti dall'album SPETTACOLINEWS.IT pubblicato quell'anno, "Uprising") ma anche classici del suo repertorio come Positive Vibration, No Woman, No Cry, Jamming, Exodus e Is This Love. Get Up Stand Up sarebbe stato ufficialmente l'ultimo brano proposto live. Anni dopo Roger Steffens, biografo ufficiale di Marley, dichiarò: «Bob salì su quel palco sapendo di essere condannato ma, ascoltando lo show, non ci sono segni di dolore, nessuna debolezza: è un'emozione straordinaria». In esclusiva per le edicole, la collana "Bob Marley" proseguirà fino a dicembre con successi intramontabili come "Legend", album reggae più venduto al mondo: sono già disponibili le prime uscite, "UPRISING"; "CATCH A FIRE" e "NATTY DREAD". -

Bob Marley Poems

Bob marley poems Continue Adult - Christian - Death - Family - Friendship - Haiku - Hope - Sense of Humor - Love - Nature - Pain - Sad - Spiritual - Teen - Wedding - Marley's Birthday redirects here. For other purposes, see Marley (disambiguation). Jamaican singer-songwriter The HonourableBob MarleyOMMarley performs in 1980BornRobert Nesta Marley (1945- 02-06)February 6, 1945Nine Mile, Mile St. Ann Parish, Colony jamaicaDied11 May 1981 (1981-05-11) (age 36)Miami, Florida, USA Cause of deathMamanoma (skin cancer)Other names Donald Marley Taff Gong Profession Singer Wife (s) Rita Anderson (m. After 1966) Partner (s) Cindy Breakspeare (1977-1978)Children 11 SharonSeddaDavid Siggy StephenRobertRohan Karen StephanieJulianKy-ManiDamian Parent (s) Norval Marley Sedella Booker Relatives Skip Marley (grandson) Nico Marley (grandson) Musical careerGenres Reggae rock Music Instruments Vocals Guitar Drums Years active1962-1981Labels Beverly Studio One JAD Wail'n Soul'm Upsetter Taff Gong Island Associated ActsBob Marley and WailersWebsitebobmarley.com Robert Nesta Marley, OM (February 6, 1945 - May 11, 1981) was Jamaican singer, songwriter and musician. Considered one of the pioneers of reggae, his musical career was marked by a fusion of elements of reggae, ska, and rocksteady, as well as his distinctive vocal and songwriting style. Marley's contribution to music has increased the visibility of Jamaican music around the world and has made him a global figure in popular culture for more than a decade. During his career, Marley became known as the Rastafari icon, and he imbued his music with a sense of spirituality. He is also considered a global symbol of Jamaican music and culture and identity, and has been controversial in his outspoken support for marijuana legalization, while he has also advocated for pan-African. -

Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent's Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in Their Children's

Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent’s Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in their Children’s Learning By Carrie Makarewicz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elizabeth Deakin, Chair Professor Karen Chapple Professor Susan Stone Fall 2013 Examining the influence of the urban environment on parent’s time, energy, and resources for engagement in their children’s learning © Copyright 2013 by Carrie Makarewicz All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent’s Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in their Children’s Learning by Carrie Makarewicz Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Elizabeth Deakin, Chair Decades of research have shown that parents play a critical role in their children’s education and learning, particularly if they engage with their children’s education at home, get involved in their children’s schools, and involve their children in community-based activities and programs that provide additional types of learning and socialization. However, research has also identified that barriers in the urban environment often prevent parents from being more fully engaged, including barriers related to transportation, housing, and neighborhood safety. These urban environmental barriers are rarely mentioned in the current school reform debates, nor are there detailed analyses of how actual environmental issues present barriers to parents. This dissertation fills this gap by examining how the urban environment affects parents’ time, energy, and resources for engagement in their children’s learning. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent's Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in their Children's Learning Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2gp9j8dz Author Makarewicz, Carrie L. Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent’s Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in their Children’s Learning By Carrie Makarewicz A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Elizabeth Deakin, Chair Professor Karen Chapple Professor Susan Stone Fall 2013 Examining the influence of the urban environment on parent’s time, energy, and resources for engagement in their children’s learning © Copyright 2013 by Carrie Makarewicz All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Examining the Influence of the Urban Environment on Parent’s Time, Energy, and Resources for Engagement in their Children’s Learning by Carrie Makarewicz Doctor of Philosophy in City and Regional Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor Elizabeth Deakin, Chair Decades of research have shown that parents play a critical role in their children’s education and learning, particularly if they engage with their children’s education at home, get involved in their children’s schools, and involve their children in community-based activities and programs that provide additional types of learning and socialization. However, research has also identified that barriers in the urban environment often prevent parents from being more fully engaged, including barriers related to transportation, housing, and neighborhood safety. -

JULY 2015 Ianohio.Com 2 IAN Ohio “We’Ve Always Been Green!” JULY 2015

JULY 2015 ianohio.com 2 IAN Ohio “We’ve Always Been Green!” www.ianohio.com JULY 2015 Editor’s Corner weekend (24-26) this month, Our Irish Man on the Street then Dublin the week after, and talks Sports, and Off the Shelf has Ohio Celtic the week after that. a great auld find in a book, Festi- Festivals rely on you to come, val Focus continues with the July no matter the weather or the and August festivals and great competition for your dollar, so reports from the Irish Fields of please help insure our heritage Glory in American GAA Football has enough support to preserve, and Hurling right here in and promote and present in a fun around Ohio show our heritage filled format. Get up, show up is thriving, thanks to those who John O’Brien, Jr. and lift up has been my mantra indeed, step into the arena. for as long as I have entered the Sheila Murphy, Paul Callahan, 2015 is half gone; in my near arena, chinks in armor slow but Judge Mike Donnelly and Judge half century, never has a year cannot fell; we need you more Brendan Sheehan were all had so much strife, and so much than ever to lift up, by showing honored this month by various honor; progress in moments up, before festivals fade into organizations. Sometimes that of sickening pain, and in and memory and are only recalled slips by and the broader world out finally “getting it” illumi- in stories of our past. For want doesn’t see it, know it, and savor nation. -

22. Internationales Dokumentarfilmfestival München 02

DOK FEST 22. Internationales Dokumentarfilmfestival München 02. bis 10. Mai 2007 Arri, Atelier, Filmmuseum, Vortragssaal der Stadtbibliothek Am Gasteig, Pinakothek der Moderne, HFF www.dokfest-muenchen.de Veranstalter: Filmstadt Munchen̈ e.V., Internationales Dokumentarfilmfestival München e.V., zusammen mit Münchner Stadtbibliothek Am Gasteig, Münchner Filmmuseum, Kulturreferat und Referat fur̈ Arbeit und Wirtschaft der Landeshauptstadt München, gefördert von der Bayerischen Staatskanzlei im Rahmen der Bayerischen Filmförderung, vom Auswärtigen Amt, dem Bayerischen Rundfunk und der Telepool GmbH 3sat | ZDF ORF SRG ARD 3satdokumentarfilm Vier Filme beim 22. DOK.FEST München Barburka von Katja Schupp & Hartmut Seifert Deutschland 2006 (ZDF/3sat) Hardcore Chambermusic von Peter Liechti Schweiz 2006 (SF/3sat) Josephson Bildhauer von Matthias Kälin & Laurin Merz Schweiz 2007 (SF/3sat) Thomas Harlan – Wandersplitter von Christoph Hübner Deutschland 2006 (WDR/3sat) anders fernsehen München Altstadt *** Nur 3 Minuten zum Marienplatz Zentraler können Sie nicht wohnen! Hotterstraße 4 D-80331 München Tel.: (089) 232590 · Fax (089) 23259-127 email [email protected] Liebe Kinofreunde, liebe DOK.FEST-Fans, Es ist wieder Mai, und wieder ist DOK.FEST.ZEIT. Im 22. Jahr bieten wir Ihnen wie immer ein vielfältiges, informatives und sicher begeisterndes Programm, für Sie ausgewählt aus über 1.200 Filmen. Noch nie in der gesamten Kinogeschichte war der künstlerische Dokumentarfilm weltweit so erfolg- reich wie in 2006. Wir zeigen Ihnen Höhepunkte des vergangenen Jahres, viele Preisträger anderer Fes- tivals, Premieren, Entdeckungen und Lieblingsfilme, die wir Ihnen herzlich empfehlen. Dokumentarfilme sind politisch, feiern die Siege und beklagen die Niederlagen im Kampf um die Menschenrechte, diskutieren Welthandel, Ernäh- rung, Migration, mischen sich ein, erinnern an ver- gessene Kriege, an Opfer und Täter. -

Energiesparen

unabhängig, überparteilich, legal hanfj ournal.de | Ausgabe #130 | April 2011 clubmed guerilla growing wirtschaft cooltour fun&action news Schöne Neue Welt - Stromzähler 2.0 4 5 10 12 16 24 Energiesparen 7 HYDROPONIK klein geschrieben Letzter Teil der großen Serie ASSASSIN 12 Interview auf Jamaika erzeit denkt wohl jeder über seine Stromquelle nach und fragt sich, wo er mögliche Einsparungen vorneh- 23 GLOBAL MARIHUANA MARCH Dmen könnte. Stromversorger modernisieren aus dem Berlin und Wien am 07. Mai selben Grunde ihre Stromzähler von altbekannten Drehrad- zählern zu technisch weitaus höher entwickelten digitalen Zählgeräten. Mitt lerweile sind sie sogar zur Pfl ichteinrich- tung in Neubauten geworden, die mit sekundengenauen Messungen über den Stromverbrauch der Bewohner infor- mieren und Stromfresser im System sofort entlarven. Die Übermitt lung der Daten soll Stromspitz enlasten vermeiden und die Netz e besser steuerbar machen, stellt aber einen tieferen Eingriff in die Privatsphäre der Nutz er dar, als es vorerst den Anschein macht. Schließlich lassen sich direkte Rückschlüsse auf die Lebensgewohnheiten der Kundschaft anstellen und deren Tagesabläufe ließen sich widerspie- geln. Das sagen zumindest einige Experten wie auch Juristen, denen ein solch immenser Eingriff in die Privatsphäre des Eigenheimes recht unheimlich erscheint. So wäre es mög- lich mit entsprechender Software das Verhalten in der Pri- vatwohnung in ungeahntem Maße nachzuvollziehen und auszuwerten, sagt Patrick Breyer, Jurist aus dem hessischen Wald-Michelbach. Daher habe er eine Petition ins Leben gerufen, die sich gegen ein Gesetz von 2008 wendet, dass die Pfl icht vom Einbau digitaler Stromzähler in Neubauten bestimmt. Seit Januar 2010 fallen auch sanierte Altbauten unter das Gesetz . -

Do the Reggae Reggae Von Pocomania Bis Ragga Und Der Mythos Bob Marley

Do the Reggae Reggae von Pocomania bis Ragga und der Mythos Bob Marley René Wynands 1 René Wynands „Do the Reggae“ Zu diesem Buch An keinem Ort der Welt wird mehr Musik produziert als auf der Karibik- insel Jamaika. Reggae ist dort echte „Volksmusik“, die die Erlebnisse, Wün- sche und Ansichten einer quirlig-chaotischen Gesellschaft reflektiert. Hauptvertreter des Reggae war Bob Marley (1945–1981), der in den 70ern zu einer Kultfigur wurde. Wynands’ Buch zeichnet die Geschichte der Reg- gae-Musik bis in unsere Tage nach und stellt dabei den Mythos Bob Mar- ley in seinen musikgeschichtlichen Kontext. Der Autor gibt einen tiefen Einblick in Herkunft, Entwicklung und in Spielweisen einer faszinieren- den Musik, deren innovative Kraft die euro-amerikanische Popmusik seit 35 Jahren entscheidend prägt und derzeit umkrempelt. René Wynands, geboren 1965 in Bochum, studierte Kunstgeschichte, Filmwissenschaften und Philosophie. Er ist versierter Kenner des Reggae und arbeitet als freier Musikjournalist und Designer. René Wynands „Do the Reggae“ Reggae von Pocomania bis Ragga und der Mythos Bob Marley Mit 23 Abbildungen ISBN 3-492-18409-X (Pieper) ISBN 3-7957-8409-3 (Schott) Originalausgabe Januar 1995 beim Pieper-Verlag und Schott. PDF-Ausgabe März 2000 © René Wynands Herstellung: oktober Kommunikationsdesign Inhalt Vorwort zu PDF-Ausgabe 11 Vorwort 13 Einleitung 17 Pocp Man Jam Die Ursprünge der jamaikanischen Musik (16. Jhd.–19. Jhd.) 22 Boogie In My Bones Vom Calypso zum Jamaican Rhythm an Blues (19. Jhd.–1962) 26 Judge Not Bob Marleys erste Schritte (1945-1962) 34 Train To Skaville Der Ska (1962–1966) 46 Simmer Downs Bob Marley im „Studio One“ (1963–1966) 54 By The Rivers Of Babylon Die Rastafari-Religion 60 Get Ready, Let’s Do Rocksteady Die Rocksteady-Jahre (1966/67) 72 Mellow Mood Bob Marley zwischen den Stilen (1966–1968) 78 Do The Reggay Der frühe Reggae (1968–ca. -

Reggae's Poet Laureate Sang for the Downtrodden

M i c h a e l W a d d a c o r p r e s e n t s Strange Brew Celebrating seminal rock music | Edition 12 | Monday October 1 2007 A portrait of Bob Marley (1945-1981) Reggae’s poet laureate sang for the downtrodden Brought up in squalid conditions in Trenchtown, Kingston, as Jamaica underwent the death throes of British colonial rule, Robert Nesta Marley gradually transformed himself – with the help of his fellow musicians, producers, promoters and the international media – from a fringe “rude boy” singing crude and lively ska music for a comparatively small following of West Indian fans into an iconic, rock-star-type purveyor of thought-provoking reggae fuelled by his burning desire, as a generational spokesperson and a poet of the oppressed, to see our world emancipated from all forms of slavery, injustice and oppression. While little of Marley’s political and spiritual dream may have materialised during his tragically foreshortened life, one cannot help sensing in the early years of the new millennium that the Poet Laureate of Reggae may not have lived his life entirely in vain as a poet and prophet. Our world has changed in many respects since Marley’s death in 1981 – and one cannot help knowing and foreseeing that far bigger political, social, economic and cultural changes will occur over the next 25 years. In many respects, he was a visionary Bob Marley … hip, happy, cool, gifted and the ahead of his time: a spiritual prophet, a undisputed Poet Laureate of Reggae. revolutionary messenger and an African Renaissance poet. -

In This Issue

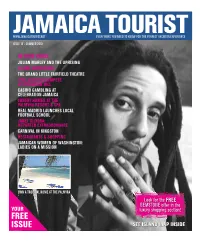

JAMAICA TOURIST WWW.JAMAICATOURIST.NET EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW FOR THE PERFECT VACATION EXPERIENCE ISSUE 15 - SUMMER 2010 IN THIS ISSUE JULIAN MARLEY AND THE UPRISING ISLAND ADVENTURES THE GRAND LITTLE FAIRFIELD THEATRE LPGA GOLFERS COMPETE AT CINNAMON HILL CASINO GAMBLING AT CELEBRATION JAMAICA LUXURY HOMES AT THE PALMYRA RESORT & SPA REAL MADRID LAUNCHES LOCAL FOOTBALL SCHOOL JANET SILVERA: REPORTER EXTRAORDINAIRE CARNIVAL IN KINGSTON RESTAURANTS & SHOPPING JAMAICAN WOMEN OF WASHINGTON: LADIES ON A MISSION OWN A TROPICAL HOME AT THE PALMYRA Look for the FREE GEMSTONE offer in the YOUR luxury shopping section! FREE ISSUE SEE ISLAND MAP INSIDE THE SWEET TASTE OF JAMAICA rought to the West Indies from Southeast Asia, the mango is Jamaica’s most popular fruit. Every year, both children and adults eagerly anticipate mango season. Colorful, sweet and juicy, the mango usually ripens sometime in May and spreads its fruity flavors around the island until July. Enjoy as many of Bthe different varieties of mangoes as you can during your visit, they just seem to taste sweeter in Jamaica! Cultivated in many tropical and subtropical regions levels of B vitamins, particularly B6, vitamin K, amino acids, potassium and copper are also present. Even the around the world, the first mango plant is said to have peel and the pulp are full of antioxidant carotenoids and polyphenols as well as omega-3 and -6 fatty acids. arrived in Jamaica in 1782 aboard Lord Rodney’s ship Additionally, mangoes are used as aphrodisiacs... ‘HMS Flora’, who had captured the plant from a French Some people simply tear off the fruit’s skin with their teeth and eat the sweet flesh ‘au natural’ while others ship on the high seas. -

INTERNO RASTA 12-05-09 22-05-2009 13:07 Pagina 1

INTERNO RASTA 12-05-09 22-05-2009 13:07 Pagina 1 Stampa Alternativa INTERNO RASTA 12-05-09 22-05-2009 13:07 Pagina 2 Dedico questo lavoro a mi Reina, I-ndrea, che amo. Al prezioso supporto dei miei genitori, Anna e Massimo. Ai traguardi recentemente raggiunti dai miei fratelli Michele e Alberto (in particolare il matrimonio di quest’ultimo con Sara, concomitante con l’uscita di questo libro). graphic designer Daisy Jacuzzi STAMPA ALTERNATIVA / NUOVI EQUILIBRI Casella Postale 97 – 01100 Viterbo fax: 0761 352751 e-mail: [email protected] sito: www.stampalternativa.it e-mail: [email protected] ISBN 978-88-6222-085-9 © 2008 Lorenzo Mazzoni © 2009 Stampa Alternativa/Nuovi Equilibri Questo libro è rilasciato con licenza Creative Commons-Attribuzione-Non commerciale-Non opere derivate 2.5 Italia. Il testo integrale della licenza è disponibile all’indirizzo http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/2.5/it/. L’autore e l’editore inoltre riconoscono il principio della gratuità del prestito bibliotecario e sono contrari a norme o direttive che, monetizzando tale servizio, limitino l’accesso alla cultura. Dunque l’autore e l’editore rinunciano a riscuotere eventuali introiti derivanti dal prestito bibliotecario di quest’opera. Per maggiori informazioni, si consulti il sito «Non Pago di Leggere», campagna europea contro il prestito a pagamento in biblioteca <http://www.nopago.org/>. INTERNO RASTA 12-05-09 22-05-2009 13:07 Pagina 3 RASTA MARLEY LE RADICI DEL REGGAE LORENZO MAZZONI INTERNO RASTA 12-05-09 22-05-2009 13:07 Pagina 4 LA REGINA DEL SUD SORGERÀ NEL GIORNO DEL GIU- DIZIO E CONDANNERÀ E SCONFIGGERÀ QUESTA GENERAZIONE CHE NON HA ASCOLTATO LA PREDICA DELLE MIE PAROLE: PERCHÉ ELLA VENNE SIN DAI CONFINI DELLA TERRA, SOLO PER ASCOLTARE LA SAGGEZZA DI SALOMONE.