Report on the Military Lending Act and the Effects of High Interest Rates on Readiness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities A Financial System That T OF EN TH M E A Financial System T T R R A E P A E S That Creates Economic Opportunities D U R E Y H T Nonbank Financials, Fintech, 1789 and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, TREASURY JULY 2018 2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Offices • www.treasury.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary T OF EN TH M E T T R R A E P A E S D U R E Y H T 1789 Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan- dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji, Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel, Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz, Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver. ii A Financial System That Creates Economic -

Adjustable-Rate Mortgage (ARM) Is a Loan with an Interest Rate That Changes

The Federal Reserve Board Consumer Handbook on Adjustable-Rate Mortgages Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System www.federalreserve.gov 0412 Consumer Handbook on Adjustable-Rate Mortgages | i Table of contents Mortgage shopping worksheet ...................................................... 2 What is an ARM? .................................................................................... 4 How ARMs work: the basic features .......................................... 6 Initial rate and payment ...................................................................... 6 The adjustment period ........................................................................ 6 The index ............................................................................................... 7 The margin ............................................................................................ 8 Interest-rate caps .................................................................................. 10 Payment caps ........................................................................................ 13 Types of ARMs ........................................................................................ 15 Hybrid ARMs ....................................................................................... 15 Interest-only ARMs .............................................................................. 15 Payment-option ARMs ........................................................................ 16 Consumer cautions ............................................................................. -

Overdraft: Payment Service Or Small-Dollar Credit?

March 16, 2020 Overdraft: Payment Service or Small-Dollar Credit? Funding Gaps in Consumer Finances Figure 1. Annual Interest and Noninterest Income One of the earliest documented cases of bank overdraft U.S. Commercial Banks, 1970-2018 ($ millions) dates back to 1728, when a Royal Bank of Scotland customer requested a cash credit to allow him to withdraw more money from his account than it held. Three centuries later, technologies, such as electronic payments (e.g., debit cards) and automated teller machines (ATMs), changed the way consumers use funds for retail purchases, transacting more frequently and in smaller denominations. Accordingly, today’s financial institutions commonly offer point-of-sale overdraft services or overdraft protection in exchange for a flat fee around $35. Although these fees can be large relative to the transaction, alternative sources of short-term small-dollar funding, such as payday loans, deposit advances, and installment loans, can be costly as well. Congress has taken an interest in the availability and cost of providing consumers funds to meet Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). their budget shortfalls. Legislation introduced in the 116th Congress (H.R. 1509/S. 656 and H.R. 4254/S. 1595) as well Banks generate noninterest income in a number of ways. as the Federal Reserve’s real-time payments initiative could For example, a significant source of noninterest income impact consumer use of overdraft programs in various comes from collecting fees for deposit accounts services, ways. (See “Policy Tools and Potential Outcomes” below such as maintaining a checking account, ATM withdrawals, for more information.) The policy debate around this or covering an overdraft. -

LOAN RATES America First Credit Union Offers Members Competitive Loan Rates, Listed Below

LOAN RATES America First Credit Union offers members competitive loan rates, listed below. The annual percentage rates (APR) quoted are based on approved credit. Rates may be higher, depending on your credit history and other underwriting factors. Our loan offices will discuss your application and available rates with you. Variable APRs may increase or decrease monthly. Go to americafirst.com or call 1-800-999-3961 for more information. EFFECTIVE: OCTOBER 1, 2021 VARIABLE APR FIXED APR FEE DISCLOSURES VEHICLE 2.99% - 18.00% 2.99% - 18.00% ANNUAL PERCENTAGE RATE (APR) FOR PURCHASES 60-MONTH DECLINING RATE AUTO N/A 3.24% - 18.00% When you open your account, the applicable APR is based on creditworthiness. SMALL RV LOAN 4.49% - 15.24% 5.49% - 16.24% After that, your APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. RV LOAN 4.49% - 15.74% 5.49% - 16.74% APR FOR CASH ADVANCES & BALANCE TRANSFERS When you open your account, the applicable APR is based on creditworthiness. RV BALLOON N/A 5.49% - 6.74% After that, your APR will vary with the market based on the Prime Rate. PERSONAL 8.49% - 18.00% 9.49% - 18.00% HOW TO AVOID PAYING INTEREST ON PURCHASES LINE OF CREDIT 15.24% - 18.00% Your due date is the 28th day of each month. We will not charge any interest on the portion of the purchases balance that you pay by the due date each month. SHARE-SECURED LINE OF CREDIT 3.05% FOR CREDIT CARD TIPS FROM THE CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION CONSUMER SHARE LOAN + 3.00% BUREAU CREDIT BUILDER PLUS 10.00% To learn more about factors to consider when applying for or using a credit card, visit the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at CERTIFICATE ACCOUNT * 3.00% consumerfinance.gov/learnmore. -

Stopping the Payday Loan Trap Alternatives That Work, Ones That Don’T

Stopping the payday Loan trap AlternAtives thAt Work, ones thAt Don’t NCLC® NATIONAL CONSUMER June 2010 L AW C E N T E R® © Copyright 2010, National Consumer Law Center, Inc. All rights reserved. About the Authors Lauren K. Saunders is the Managing Attorney of NCLC’s Washington, DC office, where she handles legislative, administrative and other advocacy efforts on behalf of low income consumers. She contributes to several NCLC publications, including Fair Credit Reporting, Fair Debt Collection and Consumer Banking and Payments Law. She graduated magna cum laude from Harvard Law School where she was an Executive Editor of the Harvard Law Review, and holds a Masters in Public Policy from Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government and a B.A., Phi Beta Kappa, from Stanford University. Leah A. Plunkett is a staff attorney at NCLC, where she focuses on predatory small dollar loans, auto policy, protection of exempt funds, and the consumer needs of domestic violence survivors. Before coming to NCLC, Leah clerked in the United States District Court for the District of Maryland and established the Youth Law Project at New Hampshire Legal Assistance. Leah is a cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School, where she was on the board of both the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau and HLS for Choice. Carolyn Carter is NCLC’s Deputy Director for Advocacy. She is a contributing author to Cost of Credit, Truth in Lending, Unfair and Deceptive Acts and Practices and several other NCLC treatises. Prior to joining NCLC, she worked for legal services programs in Ohio and Pennsylvania. -

Payday Lending in America

An overview from Oct 2013 Report 3 in the Payday Lending in America series Payday Lending in America: Policy Solutions Overview About 20 years ago, a new retail financial product, the payday loan, began to spread across the United States. It allowed a customer who wanted a small amount of cash quickly to borrow money and pledge a check dated for the next payday as collateral. Twelve million people now use payday loans annually, spending an average of $520 in interest to repeatedly borrow an average of $375 in credit. In the 35 states that allow this type of lump-sum repayment loan, customers end up having to borrow again and again—paying a fee each time. That is because repaying the loan in full requires about one-third of an average borrower’s paycheck, not leaving enough money to cover everyday living expenses without borrowing again. In Colorado, lump-sum payday lending came into use in 1992. The state was an early adopter of such loans, but the situation is now different. In 2010, state lawmakers agreed that the payday loan market in Colorado had failed and acted to correct it. Legislators forged a compromise designed to make the loans more affordable while granting the state’s existing nonbank lenders a new way to provide small-dollar loans to those with damaged credit histories. The new law changed the terms for payday lending from a single, lump-sum payment to a series of installment payments stretched out over six months and lowered the maximum allowable interest rates. As a result, borrowers in Colorado now pay an average of 4 percent of their paychecks to service the loans, compared with 36 percent under a conventional lump-sum payday loan model. -

MLA Faqs 08.22

Frequently Asked Questions about the Defense Department’s Military Lending Act Regulations The following is intended to help pawnbrokers prepare for the October 3, 2016 mandatory compliance date for the expanded Military Lending Act (MLA) regulations. This information is not intended as, and should not be used as, a substitute for guidance from your local lawyer. What is the Military Lending Act? The MLA was enacted by Congress in 2006, and the DOD adopted a regulation to implement it in 2007, but did not cover pawn transactions. The DOD expanded the scope of the regulation to cover additional consumer credit products on July 22, 2015 (“2015 regulation”), and specifically mentioned pawn transactions. When does compliance with the DOD’s 2015 regulation become mandatory for pawn transactions? October 3, 2016, unless extended by the DOD or otherwise by Congress or a court of law. What types of transactions does DOD’s expanded regulation govern? The 2015 regulation applies to pawns if the borrowers or pledgers are active duty service members, their spouse or other dependent who receives 51% or more of their support from the service member. These consumers are “covered borrowers”. No traditional non-recourse pawn transaction entered into before October 3, 2016 is affected by the 2015 regulation. The 2015 regulation does not affect pawns entered into before your customer became an active duty service member or dependent of one. What are the key requirements of DOD’s regulation? The 2015 regulation: • caps the maximum Annual Percentage Rate -

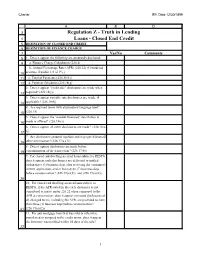

Regulation Z - Truth in Lending 4 Loans - Closed End Credit 5 DEFINITION of CLOSED END CREDIT 6 DEFINITION of FINANCE CHARGE 7 Yes/No Comments 8 1

Charter Eff. Date 12/30/1899 A B D 3 Regulation Z - Truth in Lending 4 Loans - Closed End Credit 5 DEFINITION OF CLOSED END CREDIT 6 DEFINITION OF FINANCE CHARGE 7 Yes/No Comments 8 1. Does it appear the following are accurately disclosed: 9 a. Finance Charge Calculation (226.4) b. Annual Percentage Rate (APR) (226.22) (Considered 10 accurate if within 1/8 of 1%.) 11 c. Total of Payments (226.18(h)) 12 d. Payment Schedules (226.18(g) 2. Does it appear "credit sale" disclosures are made when 13 required? (226.18(j)) 3. Does it appear variable-rate disclosures are made, if 14 applicable? (226.18(f)) 4. Are required terms with explanatory language used? 15 (226.18) 5. Does it appear the “amount financed” itemization is 16 made or offered? (226.18(c)) 6. Does it appear all other disclosures are made? (226.18(a- 17 r)) 7. Are disclosures grouped together and segregated from all 18 other information? (226.17(a)(1)) 8. Does it appear disclosures are made before 19 consummation of the transaction? (226.17(b)) 9. For closed end dwelling-secured loans subject to RESPA, does it appear early disclosures are delivered or mailed within three (3) business days after receiving the consumer's written application, and at least seven (7) business days before consummation? (226.19(a)(1)) and (226.19(a)(2)) 20 10. For closed end dwelling-secured loans subject to RESPA, if the APR stated in the early disclosure is not considered accurate under 226.22 when compared to the APR at consumation, does it appear corrected disclosures of all changed terms, including the APR, are provided no later than three (3) business days before consummation? 21 (226.19(a)(2)) 11. -

Payday Loans = Costly Cash

Payday Loans = Costly Cash Payday lenders lure consumes with messages like “Get cash until payday! $100 or more…fast!” These ads are on the radio, television, the Internet and even in the mail. These types of loans go by a variety of names: payday loans, cash advance loans, check advance loans, post-dated check loans or deferred deposit check loans – and they come at a very high price. How payday loans work • Usually, a borrower writes a personal check payable to the lender for the amount he or she wishes to borrow plus a fee. The company gives the borrower the amount of the check minus the fee. • Fees charged for payday loans are usually a percentage of the face value of the check or a fee charged per amount borrowed - say, for every $50 or $100 loaned. • If you extend or "roll-over" the loan - say for another two weeks - you will pay the fees for each extension. • Payday lenders create a cycle of debt, encourage chronic borrowing and hold annual interest rates as high at 400%. • Under the Truth in Lending Act, the cost of payday loans - like other types of credit - must be disclosed. Among other information, you must receive, in writing, the finance charge (a dollar amount) and the annual percentage rate or APR (the cost of credit on a yearly basis). • Let's say you write a personal check for $115 to borrow $100 for up to 14 days. The check casher or payday lender agrees to hold the check until your next payday. At that time, depending on the particular plan, the lender deposits the check, you redeem the check by paying the $115 in cash, or you roll-over the check by paying a fee to extend the loan for another two weeks. -

V. Lending — Military Lending Act

V. Lending — Military Lending Act Military Lending Act In addition, among other provisions, the MLA, as implemented by DoD: Background • Provides an optional safe harbor from liability for certain Examiners should reference the Military Lending Act procedures that creditors may use in connection with examination procedures (Chapter V-13.1 in the Compliance identifying covered borrowers; Examination Manual) for consumer credit transactions occurring on or after October 3, 2016, as relevant. For • Requires creditors to provide written and oral disclosures consumer credit transactions occurring prior to these dates, in addition to those required by TILA; examiners should reference the Talent Amendment examination procedures (Chapter V-12.1 in the Compliance • Prohibits certain loan terms, such as prepayment penalties, Examination Manual). mandatory arbitration clauses, and certain unreasonable notice requirements; and The Military Lending Act1 (MLA), enacted in 2006 and implemented by the Department of Defense (DoD), protects • Restricts loan rollovers, renewals, and refinancings by active duty members of the military, their spouses, and their some types of creditors. dependents from certain lending practices. These practices Statutory amendments to the MLA in 2013 granted could pose risks for service members and their families, and enforcement authority for the MLA’s requirements to the could pose a threat to military readiness and affect service agencies specified in section 108 of TILA.7 These agencies member retention. include the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve The DoD regulation2 implementing the MLA contains System, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), limitations on and requirements for certain types of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the National consumer credit extended to active duty service members Credit Union Administration, the Office of the Comptroller and their spouses, children, and certain other dependents of the Currency, and the Federal Trade Commission. -

Mortgage Rates

Mortgage Rates Rate Minimum Time Maximum Maximum Interest Maximum Adjustment Program APR1 Down Initial Rate Annual Lifetime Rate Term After Fixed Payment is Fixed Increase Increase Period 5/1 ARM 2.600% 2.432% 30 Years 5% 5 Years Annual 2% 6% 1-Year ARM2 3.000% 2.321% 30 Years 5% 1 Year Annual 2% 6% Welcome Home As low as 4.125% 4.400% 20 Years Loan $04 30-Year Fixed 3.125% 3.313% 30 Years 5% 15-Year Fixed 2.500% 2.681% 15 Years 5% 9.000% Land Loans 9.474% 15 Years 30% (fixed rate) Second 6.000%3 6.434% 15 Years N/A Mortgage Loan (fixed rate) 1 Annual Percentage Rate (APR) 2 Non-conforming 1-year ARMs are available. Please call 704.375.0183 x4525 for rates. 3 Rate shown is the lowest rate available and may be subject to upward adjustment based on credit score and the Loan-to-Value (LTV) ratio. 4 Qualifications apply. Insured by NCUA | Equal Housing Lender Rev. 09.01.2021 . 02.12.2019 adjustable rate mortgage (arm) examples Maximum Rate Maximum Initial Interest Initial Monthly Loan Amount Loan Term APR at First Payment at First Rate Payment P&I Adjustment Adjustment P&I $100,000 30 Years 3.130% 2.889% $428.38 5.130% $527.42 $100,000 30 Years 3.000% 2.843% $421.60 5.000% $519.74 $100,000 30 Years 2.880% 2.801% $414.89 4.880% $512.11 $100,000 30 Years 3.500% 3.020% $449.04 5.500% $550.82 − Interest rates and payments may increase after loan closing. -

Microfinance TRAPS

Microfinance TRAPS The Microfinance Transparent Pricing Supervision Handbook June 2013 A publication sponsored by TRAPS Transparent Pricing Supervision Handbook Microfinance Transparency The microfinance industry continues to grow into one that is dynamic and far-reaching. It is applied all over the world in many creative forms, and with the participation of many types of stakeholders. MicroFinance Transparency is a NGO established in 2008 to promote the welfare of poor micro- entrepreneurs, and to promote the integrity of microfinance as a poverty alleviation practice. Microfinance has long been highly transparent in some areas, but due to complications of market conditions and lack of regulation, the true price of our loan products has never been accurately measured or reported. For this reason MFTransparency believes there is a need to present information on credit products and their prices in a clear and consistent fashion. At the same time, MFTransparency sees an opportunity to provide education on the considerations microfinance Institutions (MFIs) face regarding interest rates and product pricing. Since MFTransparency’s launch in July 2008, 912 industry leaders, including MFIs and Apex Banks currently serving 60 million clients worldwide, have signed the endorser statement, and over 500 institutions have shared their pricing data on 2,000 loan products currently held by over 60 million clients. For further information, please contact: Mr Chuck Waterfield, CEO [email protected] www.mftransparency.org * Planet Rating Planet Rating is a global rating agency specialized in microfinance. Its role is to support the development of a sound microfinance sector in order to bring a positive social change. Planet Rating was created in 1999 as a department of the international NGO PlaNet Finance in order to accompany the tremendous development of microfinance services and bring the transparency that was needed to harness the growth of the sector.