Documents D'anàlisi Geogràfica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping LGBTQ Organizations in Israel

Mapping LGBTQ Organizations in Israel Summary Report Researched and Written by: Prof. Israel Katz, Adi Maoz, Dana Alfassi, Nir Levy Professional Management: Ohad Hizki & Ronit Levy June 2018 1 The following mapping was written for, about and in collaboration with, the LGBTQ organizations in Israel: 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 4 2. Executive Summary ................................................................................. 6 3. Mapping of LGBTQ Organizations in Israel ...................................... 14 Findings of the Organizational Survey .................................................................... 14 Other Activities ........................................................................................................ 20 4. Analysis of the LGBTQ Organizational Sphere ................................. 24 Boundaries—of the LGBTQ Field, Community, and Activities ............................... 24 Organizational Characteristics and Activities......................................................... 28 Inter-Organizational Collaboration ........................................................................ 32 Attitudes toward the Establishment ......................................................................... 38 5. Conclusion .............................................................................................. 43 Main Recommendations .......................................................................................... -

Education Sector Responses to Homophobic Bullying

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization GOOD POLICY AND PRACTICE IN HIV AND HEALTH EDUCATION BOOKLET 8 Education Sector Responses to Homophobic Bullying GOOD POLICY AND PRACTICE IN HIV AND HEALTH EDUCATION Booklet 8 EDUCATION SECTOR RESPONSES TO HOMOPHOBIC BULLYING Published in 2012 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2012 All rights reserved ISBN XXXXXX-X The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. Cover photos: © 2005 Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)/J. Bloch © 2006 Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)/H. McDonald © 2005 Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)/J. Bloch © 2005 Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)/Z. Muholi © 2011 BeLonG To Youth Services, Ireland © P. Pothipun © 2005 Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA)/J. Bloch © UNESCO/K. Benjamaneepairoj Designed & printed by UNESCO Printed in France CONTENTS Acronyms ............................................................................................................................4 Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................5 -

ANNUAL REPORT INTERNATIONAL LESBIAN GAY BISEXUAL TRANS and INTERSEX ASSOCIATION Table of Contents

2012 ANNUAL REPORT INTERNATIONAL LESBIAN GAY BISEXUAL TRANS AND INTERSEX ASSOCIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS 02 Vision, Mission and Strategic objectives 03 Thanks and acknowledgements Foreword from the Secretaries Generals 04 by Gloria Careaga and Renato Sabbadini A message from the Executive Director 07 by Sebastian Rocca Your Global LGBTI federation: Embracing the movement! Stockholm: global movement meets in the snow for a 09 warm and successful world conference Membership: ILGA reaches 1005 members and “talks” to 4500 LGBTI 13 organisations worldwide! Supporting the growth of LGBTI movements in 15 the Global South: ILGA’s Regional Development and Communication Project 18 World Pride in London: ILGA under the spotlight! Your voice at the United Nations: LGBTI rights are human rights! 2012 at the UN: ILGA deepens its engagement at the 19 United Nations Activism! Tools for change for the L, G, B, T and I communities 24 Second Forum on Intersex Organising 6th edition of the State Sponsored Homophobia 26 report 27 Global maps go… local! 29 ILGA stands up for lesbian rights! Activism! Tools for change for the L, G, B, T and I communities 30 Financial information 32 ILGA Executive Board and its members in 2012 FRIC AN A A IL P GA S T L H E S G I B R I A N N A * M G U A Y H * E B R I A S T E X H U G I A R L * T R R E A T N N S I * ILGA ANNUAL REPORT 2012 THIS REPort OUTLINES THE WORK undertaKEN BY ILGA staFF, board, MEMBERS AND Volunteers FroM January – DECEMBER 2012. -

Stonewall Global Workplace Briefings Europe, Middle East and Africa Pack

STONEWALL GLOBAL WORKPLACE BRIEFINGS EMEA EUROPE, MIDDLE EAST AND AFRICA PACK Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kenya, Nigeria, Poland, Qatar, Russia, South Africa, Spain, Turkey, Uganda, United Arab Emirates and United Kingdom STONEWALL GLOBAL WORKPLACE BRIEFINGS 2018 BELGIUM Population: 11+ million Stonewall Global Diversity Champions: 55 THE LEGAL LANDSCAPE In Stonewall’s Global Workplace Equality Index, broad legal zoning is used to group the differing challenges faced by organisations across their global operations. Belgium is classified as a Zone 1 country, which means sexual acts between people of the same sex are legal and clear national employment protections exist for lesbian, gay, and bi people. Two further zones exist. In Zone 2 countries, sexual acts between people of the same sex are legal but no clear national employment protections exist on grounds of sexual orientation. In Zone 3 countries, sexual acts between people of the same sex are illegal. FREEDOM OF FAMILY AND EQUALITY AND EMPLOYMENT GENDER IDENTITY IMMIGRATION EXPRESSION, RELATIONSHIPS ASSOCIATION AND ASSEMBLY Articles 19 and 25 Sexual acts between Article 3 of the federal The Federal Transgender Law The Aliens Act enables of the Constitution people of the same sex are Anti-Discrimination Law of of 25 June 2017 provides trans family reunification include the right to are legal. 10 May 2007 explicitly prohibits and intersex people the right to between same-sex freedom of speech discrimination on the grounds of change their legal gender to partners. Under and expression. There is an equal age of sexual orientation and gender. male or female as well as to the Belgian Code of Articles 26 and 27 consent of 16 years for This includes discrimination change their first name. -

A Global Human Rights Approach to Pre-Service Teacher Education on Lgbtis

Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education ISSN: 1359-866X (Print) 1469-2945 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/capj20 A global human rights approach to pre-service teacher education on LGBTIs Tiffany Jones To cite this article: Tiffany Jones (2019) A global human rights approach to pre-service teacher education on LGBTIs, Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47:3, 286-308, DOI: 10.1080/1359866X.2018.1555793 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1555793 © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. Published online: 13 Dec 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 173 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=capj20 ASIA-PACIFIC JOURNAL OF TEACHER EDUCATION 2019, VOL. 47, NO. 3, 286–308 https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1555793 ARTICLE A global human rights approach to pre-service teacher education on LGBTIs Tiffany Jones School of Education, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Pre-service teacher education on LGBTI rights and inclusion is Received 29 June 2018 impacted by multiple conflicting education governance provisions Accepted 24 October 2018 ff carrying di erent risks and duties for teachers. Pre-service teacher KEYWORDS – education has an international reach catering to both international Sexuality; gender; LGBTI; pre-service teachers and domestic pre-service teachers destined for education careers and travel abroad. This paper argues that pre-service teacher education efforts focussing solely on local education treatments of LGBTI rights may leave pre-service teachers sorely underprepared for the differing education contexts they may encounter. -

A More Practical Guide to Incorporating Health Equity Domains in Implementation Determinant Frameworks Eva N

Woodward et al. Implementation Science Communications (2021) 2:61 Implementation Science https://doi.org/10.1186/s43058-021-00146-5 Communications METHODOLOGY Open Access A more practical guide to incorporating health equity domains in implementation determinant frameworks Eva N. Woodward1,2* , Rajinder Sonia Singh2,3, Phiwinhlanhla Ndebele-Ngwenya4, Andrea Melgar Castillo5, Kelsey S. Dickson6 and JoAnn E. Kirchner2,7 Abstract Background: Due to striking disparities in the implementation of healthcare innovations, it is imperative that researchers and practitioners can meaningfully use implementation determinant frameworks to understand why disparities exist in access, receipt, use, quality, or outcomes of healthcare. Our prior work documented and piloted the first published adaptation of an existing implementation determinant framework with health equity domains to create the Health Equity Implementation Framework. We recommended integrating these three health equity domains to existing implementation determinant frameworks: (1) culturally relevant factors of recipients, (2) clinical encounter or patient-provider interaction, and (3) societal context (including but not limited to social determinants of health). This framework was developed for healthcare and clinical practice settings. Some implementation teams have begun using the Health Equity Implementation Framework in their evaluations and asked for more guidance. Methods: We completed a consensus process with our authorship team to clarify steps to incorporate a health equity lens into an implementation determinant framework. Results: We describe steps to integrate health equity domains into implementation determinant frameworks for implementation research and practice. For each step, we compiled examples or practical tools to assist implementation researchers and practitioners in applying those steps. For each domain, we compiled definitions with supporting literature, showcased an illustrative example, and suggested sample quantitative and qualitative measures. -

2020 Annual Report

2020 ANNUAL REPORT TM 1 ILGA World - the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association is grateful for the support of its member organisa- tions, staff, interns, Board and Committee members who work tirelessly to make everything we do possible. A heartfelt shout-out and thank you goes to all the human rights defenders around the world for the time and energy they commit to ad- vancing the cause of equality for persons with diverse sexual orienta- tions, gender identities and gender expressions, and sex characteristics everywhere. Our deepest thanks to those who, despite the unforeseen eco- nomic hardship bestowed upon everyone by the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic, have committed to financially make our work pos- sible in 2020. We also thank one significant anonymous donor and many other companies and individuals who have made donations. We kick off the year with new activities to support local organ- isations as they follow-up on LGBTI recommendations from JANUARY 2020 the Treaty Bodies. Throughout 2020 ILGA World and our allies AT A GLANCE made sure to keep raising queer voices at the United Nations! We launch an extensive global research into laws banning ‘conversion therapies’. Protec- FEBRUARY tion from similar ineffective and cruel treat- ment is as urgent as ever! MARCH As everything turns virtual, our communities remain connected: APRIL The world comes to a grinding halt as ILGA World holds its first-ever online Board meeting, and hosts the Covid-19 pandemic erupts. Even roundtables discussing the impact and response to the Covid-19 during these difficult days, we have pandemic among LGBTI organisations. -

Booklet Program.Pub

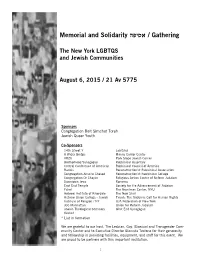

Gathering / אסיפה Memorial and Solidarity The New York LGBTQS and Jewish Communities August 6, 2015 / 21 Av 5775 Sponsors Congregation Beit Simchat Torah Jewish Queer Youth Co-Sponsors 14th Street Y Lab/Shul A Wider Bridge Manny Cantor Center ARZA Park Slope Jewish Center Brotherhood Synagogue Rabbinical Assembly Central Conference of American Rabbinical Council of America Rabbis Reconstructionist Rabbinical Association Congregation Ansche Chesed Reconstructionist Rabbinical College Congregation Or Chayim Religious Action Center of Reform Judaism Downtown Jews Romemu East End Temple Society for the Advancement of Judaism Eshel The Bronfman Center, NYU Hebrew Institute of Riverdale The New Shul Hebrew Union College - Jewish T'ruah: The Rabbinic Call for Human Rights Institute of Religion / NY UJA-Federation of New York JCC Manhattan Union for Reform Judaism Jewish Theological Seminary West End Synagogue Keshet * List in formation We are grateful to our host, The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Com- munity Center and to Executive Director Glennda Testone for their generosity and fellowship in providing facilities, equipment, and staff for this event. We are proud to be partners with this important institution. 1 Program אנוש ( תהילים קג) Enosh , Psalm 103:15-17 CBST Community Chorus, led by Music Director Joyce Rosenzweig Music: Louis Lewandowski כחציר ימיו; אנוש, .Our days are like grass כציץ השדה, כן יציץ. .We bloom like flowers of the field כי רוח עברה-בו ואיננו; ;A wind passes by, and we are no more ולא-יכירנו עוד מקומו. .our own place no longer knows us וחסד ה', מעולם ועד- עולם- על- יראיו; But the Eternal’s steadfast love is for all eternity toward וצדקתו , לבני בנים. -

No Clear Majority on Merits Evident During Prop 8 Arguments Arthur S

digitalcommons.nyls.edu Faculty Scholarship Other Publications 2013 No Clear Majority on Merits Evident During Prop 8 Arguments Arthur S. Leonard New York Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_other_pubs Part of the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Leonard, Arthur S., "No Clear Majority on Merits Evident During Prop 8 Arguments" (2013). Other Publications. 356. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/fac_other_pubs/356 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Other Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@NYLS. 12 March 27, 2013 | www.gaycitynews.com LEGAL No Clear Majority on Merits Evident During Prop 8 Arguments Kennedy offers a way out for now — the court deciding it should not have taken the case BY ARTHUR S. LEONARD significant portion of Olson’s time. show the greatest problem making factor in denying homosexuals ben- n the tenth anniversary The Prop 8 Proponents relied on up his mind. At one point, he mused efits or imposing burdens on them? of oral arguments in an advisory opinion from the Cali- that perhaps the court should not Is there any other rational decision- Lawrence v. Texas, fornia Supreme Court — issued at have granted the petition to review making that the government could the historic 2003 the request of the US Ninth Circuit the case. His questions and com- make? Denying them a job, not ruling that struck Court of Appeals — that held as a ments certainly revealed a sympa- granting them benefits of some sort, downO laws against consensual gay matter of California law that initia- thy with the plaintiff couples’ claim any other decision?” sex, the US Supreme Court took tive proponents have standing to to the right to marry, particularly Cooper’s response, a major con- up the contentious issue of same- defend their initiative if the state in emphasizing the potential harms cession, was, “Your Honor, I can- sex marriage on March 26. -

Sexual Citizenship and Homonationalism at Tel Aviv's Gay

Article Sexualities 0(0) 1–24 Being [in] the center: ! The Author(s) 2016 Reprints and permissions: Sexual citizenship and sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1363460716645807 homonationalism at sex.sagepub.com Tel Aviv’s Gay-Center Gilly Hartal Bar Ilan University, Israel Orna Sasson-Levy Bar Ilan University, Israel Abstract Tel Aviv’s Gay-Center is unique in Israel for being sponsored, managed and controlled by the municipality. This article focuses on the Gay-Center as a material, symbolic and discursive space in order to clarify the relationship between LGBT individuals and the nation. Based on an ethnographic study, we show that since its establishment the Gay- Center has undergone centralization processes as a result of being located in central Tel Aviv and by striving for LGBT mainstreaming, thereby accelerating the achievement of sexual citizenship and urban belonging. However, the expansion of sexual citizenship, which is always based on processes of inclusion and exclusion, reveals homonational practices and homonormative discourses. Since being in the city is the easiest and, at times, the only way to earn sexual citizenship, we argue that LGBT urban citizenship is an indication, a marker and thus a prerequisite of homonationalism. Keywords Homonationalism, LGBT in Israel, sexual citizenship, spatial politics, urban belonging Being [in] the center: Sexual citizenship and homonationalism at Tel Aviv’s Gay-Center1 In a demonstration protesting against the national-religious party’s (Habayit Hayehudi) veto of pro-lesbian, -

CROSSING BORDERS: Remaking Gay Fatherhood in the Global Market

CROSSING BORDERS: Remaking Gay Fatherhood in the Global Market A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of PhD Sociology in the Faculty of Humanities, School of Social Sciences. Adi Moreno 2016 Department of Sociology. CONTENTS Contents ............................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Orientation ..................................................................................................................................... 11 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 11 Introducing the Field ...................................................................................................................... 14 The state of Israel: Zionist history and state reproduction ideology .......................................... 14 LGBT Politics in Israel .............................................................................................................. 17 Israeli Surrogacy Regulations .................................................................................................... 19 Cross-Border Surrogacy ............................................................................................................. 20 Research Motivation ...................................................................................................................... 23 Research Questions and Method ................................................................................................... -

1316 Ngos Working on Diverse Human Rights Issues, from 174

1316 NGOs working on diverse human rights issues, from 174 States and territories around the world call for the renewal of the mandate of the Independent Expert on violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity 41st session of the Human Rights Council Item 8. General Debate Oral Statement Speaker: Phylesha Brown – Acton Mr. President, I have the honour to deliver this statement that was endorsed by 1316 organisations working on diverse topics. Around the world, millions of people face human rights violations and abuses because of their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity (SOGI). These abuses include: killings and extrajudicial executions; torture, rape and sexual violence; enforced disappearance; forced displacement; criminalization; arbitrary detentions; blackmail and extortion; police violence and harassment; bullying; stigmatization; hate speech; denial of one’s self defined gender identity; forced medical treatment, and/or forced sterilization; repression of the rights to freedom of expression, association and assembly, religion or belief; attacks and restrictions on human rights defenders; denial of services and hampered access to justice; discrimination in all spheres of life including in employment, healthcare, housing, education and cultural traditions; and other multiple and intersecting forms of violence and discrimination. These grave and widespread violations take place in conflict and non-conflict situations, are perpetrated by State and non-State actors (including the victims’ families and communities) and impact all spheres of life. In 2016, this Human Rights Council took definitive action to systematically address these abuses, advance positive reforms and share best practices – through regular reporting, constructive dialogue and engagement – and created an Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).