Forest Stewardship Plan Point Defiance Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 WSTC Tolling Report and Tacoma Narrows Bridge Loan Update

2021 WSTC TOLLING REPORT & TACOMA NARROWS BRIDGE LOAN UPDATE January 2021 2021 WSTC TOLLING REPORT & TACOMA NARROWS BRIDGE LOAN UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 4 SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge 7 2020 Commission Action 7 2021 Anticipated Commission Action 7 SR 99 Tunnel 8 2020 Commission Action 8 2021 Anticipated Commission Action 8 SR 520 Bridge 9 2020 Commission Action 9 2021 Anticipated Commission Action 9 I-405 Express Toll Lanes & SR 167 HOT Lanes 10 2020 Commission Action 10 2021 Anticipated Commission Action 11 I-405 Express Toll Lanes & SR 167 HOT Lanes Low Income Tolling Program Study 11 Toll Policy & Planning 12 Toll Policy Consistency 12 Planning for Future Performance & Operations 12 Looking Forward To Future Tolled Facilities 13 2021 Tolling Recommendations 14 Summary of Current Toll Rates and Revenues by Facility 16 2021 Tacoma Narrows Bridge Loan Update 17 2019-21 Biennium Loan Estimates 17 2021-23 Biennium Loan Estimates 18 Comparison of Total Loan Estimates: FY 2019 – FY 2030 18 TNB Loan Repayment Estimates 19 2021 Loan Update: Details & Assumptions 20 Factors Contributing to Loan Estimate Analysis 20 Financial Model Assumptions 21 P age 3 2021 WSTC TOLLING REPORT & TACOMA NARROWS BRIDGE LOAN UPDATE INTRODUCTION As the State Tolling Authority, the Washington State Transportation Commission (Commission) sets toll rates and polices for all tolled facilities statewide, which currently include: the SR 520 Bridge, the SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge, the I-405 express toll lanes (ETLs), the SR 167 HOT lanes, and the SR 99 Tunnel. -

SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study – December 2018

SR 16, Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3, Congestion Study FINAL December 28, 2018 Olympic Region Planning P. O. Box 47440 Olympia, WA 98504-7440 SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study – December 2018 This page intentionally left blank. SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study – December 2018 Washington State Department of Transportation Olympic Region Tumwater, Washington SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study Project Limits: SR 16 MP 8.0 to 29.1 SR 3 MP 30.4 to 38.9 SR 304 MP 0.0 to 1.6 December 2018 John Wynands, P.E. Regional Administrator Dennis Engel, P.E. Olympic Region Multimodal Planning Manager SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study – December 2018 This page intentionally left blank. SR 16 Tacoma Narrows Bridge to SR 3 Congestion Study – December 2018 Title VI Notice to Public It is the Washington State Department of Transportation’s (WSDOT) policy to assure that no person shall, on the grounds of race, color, national origin or sex, as provided by Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be otherwise discriminated against under any of its federally funded programs and activities. Any person who believes his/her Title VI protection has been violated, may file a complaint with WSDOT’s Office of Equal Opportunity (OEO). For additional information regarding Title VI complaint procedures and/or information regarding our non- discrimination obligations, please contact OEO’s Title VI Coordinator at (360) 705-7082. -

Chapter 13 -- Puget Sound, Washington

514 Puget Sound, Washington Volume 7 WK50/2011 123° 122°30' 18428 SKAGIT BAY STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA S A R A T O 18423 G A D A M DUNGENESS BAY I P 18464 R A A L S T S Y A G Port Townsend I E N L E T 18443 SEQUIM BAY 18473 DISCOVERY BAY 48° 48° 18471 D Everett N U O S 18444 N O I S S E S S O P 18458 18446 Y 18477 A 18447 B B L O A B K A Seattle W E D W A S H I N ELLIOTT BAY G 18445 T O L Bremerton Port Orchard N A N 18450 A 18452 C 47° 47° 30' 18449 30' D O O E A H S 18476 T P 18474 A S S A G E T E L N 18453 I E S C COMMENCEMENT BAY A A C R R I N L E Shelton T Tacoma 18457 Puyallup BUDD INLET Olympia 47° 18456 47° General Index of Chart Coverage in Chapter 13 (see catalog for complete coverage) 123° 122°30' WK50/2011 Chapter 13 Puget Sound, Washington 515 Puget Sound, Washington (1) This chapter describes Puget Sound and its nu- (6) Other services offered by the Marine Exchange in- merous inlets, bays, and passages, and the waters of clude a daily newsletter about future marine traffic in Hood Canal, Lake Union, and Lake Washington. Also the Puget Sound area, communication services, and a discussed are the ports of Seattle, Tacoma, Everett, and variety of coordinative and statistical information. -

Point Defiance Park: Master Plan Update

PRESENTED BY: POINT DEFIANCE PARK: BCRA, Inc. 2106 Pacific Ave, Suite 300 Tacoma, WA 98402 MASTER PLAN UPDATE 253.627.4367 TACOMA, WASHINGTON - NOVEMBER 1, 2015 bcradesign.com 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction Design Guidelines Implementation Executive Summary ....................................................... 4 Introduction .............................................................30 Development Regulations / Standards ....................................34 Public Outreach ....................................................... 4 Purpose .................................................................30 Purpose of a Development Regulation Agreement ....................34 Plan Details .......................................................... 4 Consistency with Historic Property Management Plan ..................... 31 Design Standards ....................................................34 Acknowledgments ........................................................ 5 Inadvertent Discovery Plan ........................................... 31 Temporary Uses and Locations due to Construction Activity ...........34 General Requirements ................................................... 31 Amendments to Master Plan and DRA ................................34 Public Review Process 1. Existing Character ................................................. 31 Community Input ......................................................... 6 2. Sustainability ..................................................... 31 Project Review Process .................................................. -

4. the Wedge Historic District

THE WEDGE HISTORIC DISTRICT From the National Register Nomination Summary Paragraph Tacoma, Washington lies on the banks of Commencement Bay, where the Puyallup River flows into Puget Sound. The city is 30 miles south of Seattle, north of Interstate 5, and 30 miles north of the capital city, Olympia. To the west, a suspension bridge, the Tacoma Narrows Bridge, connects the city to the Kitsap peninsula. Through the community, a main railroad line runs south to California and north to Canada, with another line crossing the Cascades into eastern Washington. The Tacoma “Wedge Neighborhood,” named for its wedge shape, is located between 6th Ave and Division Ave. from South M Street to its tip at Sprague Avenue. The Wedge lies within Tacoma's Central Addition (1884), Ainsworth Addition (1889) and New Tacoma and shares a similar history to that of the North Slope Historic District, which is north of the Wedge Neighborhood across Division Avenue, and is listed on the Tacoma, Washington and National Registers of Historic Places. LOCATION AND SETTING The Wedge Neighborhood is bounded by Division Avenue to the north and 6th Avenue to the south, both arterials that serve to distinguish the Wedge from its surrounding neighborhoods. To the east is Martin Luther King Jr. Way, another arterial, just outside of the district. The district boundary is established by the thoroughly modern MultiCare Hospital campus to the East. The development of the hospital coincides with the borders of the underlying zoning, which is Hospital Medical, the borders of which run along a jagged path north and south from approximately Division to Sixth Ave, alternating between S M St and the alley between S M St and S L St. -

Historic Places Continuation Sheet NOV """8 Ma \ \

.------------ I I~;e NPS Form 10-900 4M~~rOO24~18 (OCt. 1990) RECIEIVED United Slates Department of the Interior National Park Service .. • NOV National Register of Historic Places ·8. Registration Form INTERAGENCY RESOURCES DIVISION This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties a d distrietMMOO~I',SfOWJlQS,mplete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Fonn (National Register Bulletin lGA). Co pleJ;e88Cb item bV marlcing "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter onfycateqories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10.,9OOa).Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name __ dT"'a"cc<,o"m!lla... N""'a"'r"'r-'Ol:!w>:;sLBQ.r"-"'i"dOjq"'e'- ------------------- other names/site number _ 2. Location street & number Spann ina the Tae oma Narrows o not for publication city or town Tacoma o vicinity state Wash; ngton code ~ county _-"PCJ.j.eecIr:cC.eec- code Jl5..3..- zip code _ 3. Slate/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the NationaJ Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this IX] nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

VKP Visitorguide-24X27-Side1.Pdf

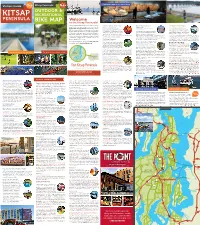

FREE FREE MAP Kitsap Peninsula MAP DESTINATIONS & ATTRACTIONS Visitors Guide INSIDE INSIDE Enjoy a variety of activities and attractions like a tour of the Suquamish Museum, located near the Chief Seattle grave site, that tell the story of local Native Americans Welcome and their contribution to the region’s history and culture. to the Kitsap Peninsula! The beautiful Kitsap Peninsula is located directly across Gardens, Galleries & Museums Naval & Military History Getting Around the Region from Seattle offering visitors easy access to the www.VisitKitsap.com/gardens & Memorials www.VisitKitsap.com/transportation Natural Side of Puget Sound. Hop aboard a famous www.VisitKitsap.com/arts-and-culture visitkitsap.com/military-historic-sites- www.VisitKitsap.com/plan-your-event www.VisitKitsap.com/international-visitors WA State Ferry or travel across the impressive Tacaoma Visitors will find many places and events that veterans-memorials The Kitsap Peninsula is conveniently located Narrows Bridge and in minutes you will be enjoying miles offer insights about the region’s rich and diverse There are many historic sites, memorials and directly across from Seattle and Tacoma and a short of shoreline, wide-open spaces and fresh air. Explore history, culture, arts and love of the natural museums that pay respect to Kitsap’s remarkable distance from the Seattle-Tacoma International waterfront communities lined with shops, art galleries, environment. You’ll find a few locations listed in Naval, military and maritime history. Some sites the City & Community section in this guide and many more choices date back to the Spanish-American War. Others honor fallen soldiers Airport. One of the most scenic ways to travel to the Kitsap Peninsula eateries and attractions. -

Dwyer Elsaesser Final Report MC Edits.Pages

Armin E. Elsaesser Fellowship 2015-2016 Final Evaluation Report Final Evaluation Report Armin E. Elsaesser Fellowship Sea Education Association 2015-2016 Fellowship Year Timothy Dwyer (W-160) http://bit.ly/2kksMKM Armin E. Elsaesser Fellowship 2015-2016 Final Evaluation Report Project Summary Awarded the 2015-2016 Armin E. Elsaesser Fellowship, I skippered my classic sloop Whistledown from her home port of Friday Harbor, Washington through the passages and inlets of Puget Sound on an exploration adventure reaching as far south as Tacoma Narrows. Between 29 July and 28 August, 2016, my rotating crew of volunteers and I were following in the wake of the United States Exploring Expedition of 1838-1843, America’s first oceangoing scientific and cartographic mission, which visited the region in the spring and summer of 1841. Where the scientists and sailors of the “Ex.Ex.” were unable to search beneath the waves for their biological specimen collections, we had the benefit of a floating, surface supplied scuba system for exploring the emerald sea, and an underwater camera system for documenting our discoveries. To see the journey in pictures, visit: http://bit.ly/2kksMKM Itinerary Prior to the voyage south, the crew spent a few days sailing Whistledown in her home waters of the San Juan Channel along San Juan Island to check systems and evaluate diving procedures for the newly acquired equipment. On 6 August, we left Friday Harbor for central Puget Sound via the Saratoga Passage, sailing, diving, and making stops at Spencer Spit State Park (Lopez Island), Deception Pass State Park (Fidalgo Island), the town of Langley (Whidbey Island), the town of Kingston (Kitsap Peninsula), Blake Island State Marine Park, and the city of Des Moines where we transferred crew and reprovisioned the vessel. -

Ita Survey of International

INTERNATIONAL TRADE ADMINISTRATION OFFICE OF TRAVEL AND TOURISM INDUSTRIES SURVEY OF INTERNATIONAL AIR TRAVELERS DATA TAPE DOCUMENTATION FOR 2009 Prepared by CIC Research, Inc. August 15, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1. General Introduction ................................................................................................... 1 2. Variable Names in Relationship to Questionnaire ...................................................... 2 3. Variable Names and Column Layout for ASCII Format .............................................. 9 4. Valid Ranges for Questionnaire Data ......................................................................... 15 5. Codebook with Question Numbers and Code Values ................................................ 23 ii TABLE OF FILES APPENDICES ON FILE A. APPEND_A.FIL - Airline Codes B. APPEND_B.FIL - Domestic Airport Codes C. APPEND_C.FIL - Foreign Airport Codes D. APPEND_D.FIL - Foreign City/Country Codes F. APPEND_F.FIL - Hotel Codes G. APPEND_G.FIL - Domestic Attraction Codes H. APPEND_H.FIL - Port of Entry Codes J. APPEND_J.FIL - Rental Car Codes M. APPEND_M.FIL - Language of Questionnaire Codes Q. APPEND_Q.FIL - Credit Card Companies iii DATA DOCUMENTATION FOR 2001 GENERAL INTRODUCTION Welcome to an explanation of the International Trade Administration, Office of Travel and Tourism Industries' (OTTI) Survey of International Air Travelers database that you have received in an electronic format. The documentation covered in this manual describes pertinent background information needed to use the OTTI database. Materials in this documentation refer to the 2009 version of the OTTI "In-Flight" Survey used by CIC Research, Inc. starting in January 2009. Specific information includes the following sections: a copy of the questionnaire with variable names the database column layout with variable names and size ranges for questionnaire data by variable name codebook In addition to the documentation included here on paper, much of the coding information is available in ASCII files. -

Reconnaissance-Level Survey of Fort Nisqually Living History Museum

Reconnaissance-level Survey of Fort Nisqually Living History Museum DAHP Project: 2019-09-06886 Project Location Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Point Defiance Park 5400 N. Pearl St., #11 Tacoma, Washington Pierce County October 4, 2019 Prepared for Metro Parks Tacoma Prepared by Sarah J. Martin SJM Cultural Resource Services 3901 2nd Avenue NE #202 Seattle, WA 98105 [email protected] Reconnaissance-level Survey October 4, 2019 Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Page 2 CONTENTS PROJECT INFORMATION …………………………………………………………………………………. 3 BRIEF HISTORICAL OVERVIEW…………..……………………………………………………………… 4 SITE OVERVIEW……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES ……………………………………………………………. 8 SOURCES ………………………………….…………………………………………………………………… 25 Figure 1. Construction crew working outside the palisade at Fort Nisqually. To the right is the southwest bastion, to the left and through the entrance is the store, and an artistically inserted Mount Rainier peeks over the palisade in the center. Photograph taken September 1, 1934. Source: Richards Studio 804-6, Tacoma Public Library Digital Collections. [Fort Nisqually Living History Museum has the original photo, sans mountain.] Reconnaissance-level Survey October 4, 2019 Fort Nisqually Living History Museum Page 3 PROJECT INFORMATION BACKGROUND & ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Metro Parks Tacoma contracted with Sarah J. Martin Cultural Resource Services in June 2019 to document physical buildings and structures that comprise Fort Nisqually Living History Museum (FNLHM). Tasks included completing physical and architectural descriptions of the site and key historic buildings and producing new and/or revised reconnaissance-level survey forms in the Department of Archaeology & Historic Preservation’s WISAARD database. The online forms include many photographs, architectural drawings, and documents associated with FNLHM. The current FNLHM property is the result of layers of history and development. -

-;'X>':-:>:X'x---:::-;-:-: .-::::::: :"::":'" class="text-overflow-clamp2"> Fort Nisqually Site AND/OR HISTORIC: Fort Ni Squally :•:•:•:•:•:•••:•:-.•:->:•>:•:; :-V^:-'-::X.';"X>-;'X>':-:>:X'x---:::-;-:-: .-::::::: :"::":'

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (Rev. 6-72) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Washington COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Pierce INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY DATE (Type all entries - complete applicable sections) UC1 lb w* illiiliM^^^^ COMMON: Fort Nisqually Site AND/OR HISTORIC: Fort Ni squally :•:•:•:•:•:•••:•:-.•:->:•>:•:; :-v^:-'-::X.';"x>-;'x>':-:>:x'x---:::-;-:-: .-::::::: :"::":'. :.-: ::::-: $&iitfiiii;$^ .-:-x : : : :-:-:-:-x-x-x-:-:-:-:-:\-:-:':-:-:-:o:-:-:-:-x-:-:-:-:-:;:::::x: : ::: x-:: :-:': : :: :-' : : :i '' : : ::: : 111 igt^W::*::*:WlS: : :: ::: :::::::-, : ::- : : : .: :-:::.: : -:.:::.:-:-::X;;:::v::;. : ;:. .; : :: : : : : x;; ^:llP;il:^:iillil1£;'i;II^^ cr- STREET AND NUMBER: KjLxJ #/ Di*yS>.so->,/ £7^" jj: X^P Near Old FOIL Lakt CITY OR TOWN: CONGRES SIGNAL DISTRICT: Du/ont V \f- i * '» +i-| #3 - H(Dnorable Julia B. Hansen STAT>E ' CODE COUNTY: CODE Washington 53 Pierc:e 053 ^•i^p^iiii^'Wi^ii CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) 0 THE PUBLIC D District Q Building 1 1 Public Public Acquisition: |~| Occupied Yes: 3 Restricted [3 Site Q Structure 1X1 Private Q In Process D Unoccupied ^ ] Unrestricted D Object Q Both Ql Being Considered 1 I Preservation work in progress L,] No PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) I I Agricultural 1 | Government | | Park 1 1 Transportation L_ Comments | | Commercial 1x1 Industrial [ | Private Residence D Other fSpeciryJ O Educational CD Military |~~| Religious [ | Entertainment [ 1 Museum [ | Scientific OWNER'S NAME: -

Metro Parks Tacoma Public Art Plan

Metro Parks Tacoma Public Art Plan Guidelines and Procedures Innovation, Excellence, Equity, Inclusiveness, Sustainability, Accountability, Safety and Fun 1 Table of Contents SECTION 1: Introduction ........................................................................................................ 4 Background ...................................................................................................................................4 Public Art Plan Overview ................................................................................................................5 Public Art Program Vision ...............................................................................................................5 Mission-Led Areas and Public Art ...................................................................................................6 SECTION 2: Policy and Funding ............................................................................................... 9 Guiding Policy for the Public Art Program .......................................................................................9 Projects Greater than $5 Million .....................................................................................................9 District Art Fund.............................................................................................................................9 Use of Funds ................................................................................................................................ 10 SECTION 3: Program