Commisssioned Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Salmon with a Side of Genetic Modification: the FDA's Approval of Aquadvantage Salmon and Why the Precautionary Principle Is E

Salmon with a Side of Genetic Modification: The FDA’s Approval of AquAdvantage Salmon and Why the Precautionary Principle is Essential for Biotechnology Regulation Kara M. Van Slyck* INTRODUCTION Over the last thirty years, once abundant wild salmon populations in the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans have declined to a mere fraction of their historic levels. As of 2016, salmon populations in Washington State’s Columbia River region are either failing to make any progress towards recovery or showing very little signs of improvement; Puget Sound salmon are only getting worse.1 In the Gulf of Maine, salmon populations dropped from five-hundred spawning adults in 1995 to less than fifty adults in 1999.2 Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar, were first designated as “endangered”3 in November 2000—the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) expanded the listing nine years later to include critical habitat along the coast of Maine as a result of little improvement to the population’s numbers.4 In the Pacific Ocean, FWS classified four significant salmon species as endangered for protection under the Endangered Species Act * Juris Doctor Candidate, Seattle University School of Law 2018. I would like to extend thanks to Professor Carmen G. Gonzalez for her valuable insight of the precautionary principle, her extensive knowledge on environmental regulations in the United States, and her unwavering support of this Note. 1. Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office, State of Salmon in Watersheds 2016, WASH. ST. RECREATION & CONSERVATION OFF., http://stateofsalmon.wa.gov/governors-report-2016/ [https:// perma.cc/6F3J-FKWE]. 2. Endangered and Threatened Species; Final Endangered Status for a Distinct Population Segment of Anadromous Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) in the Gulf of Maine, 50 C.F.R. -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Eugenomics: Eugenics and Ethics in the 21 Century

Genomics, Society and Policy 2006, Vol.2, No.2, pp.28-49 Eugenomics: Eugenics and Ethics in the 21st Century JULIE M. AULTMAN Abstract With a shift from genetics to genomics, the study of organisms in terms of their full DNA sequences, the resurgence of eugenics has taken on a new form. Following from this new form of eugenics, which I have termed “eugenomics”, is a host of ethical and social dilemmas containing elements patterned from controversies over the eugenics movement throughout the 20th century. This paper identifies these ethical and social dilemmas, drawing upon an examination of why eugenics of the 20th century was morally wrong. Though many eugenic programs of the early 20th century remain in the dark corners of our history and law books and scientific journals, not all of these programs have been, nor should be, forgotten. My aim is not to remind us of the social and ethical abuses from past eugenics programs, but to draw similarities and dissimilarities from what we commonly know of the past and identify areas where genomics may be eugenically beneficial and harmful to our global community. I show that our ethical and social concerns are not taken as seriously as they should be by the scientific community, political and legal communities, and by the international public; as eugenomics is quickly gaining control over our genetic futures, ethics, I argue, is lagging behind and going considerably unnoticed. In showing why ethics is lagging behind I propose a framework that can provide us with a better understanding of genomics with respect to our pluralistic, global values. -

Environmental Assessment for Aquadvantage ® Salmon

Environmental Assessment for AquAdvantage Salmon Environmental Assessment for AquAdvantage® Salmon An Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) bearing a single copy of the stably integrated α-form of the opAFP-GHc2 gene construct at the α-locus in the EO-1α line Aqua Bounty Technologies, Inc. Submitted to the Center for Veterinary Medicine US Food and Drug Administration For Public Display August 25, 2010 Page 1 of 84 August 25, 2010 Environmental Assessment for AquAdvantage Salmon Table of Contents (Page 1 of 4) Title Page ............................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents ................................................................................................................. 2 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................... 6 List of Figures ...................................................................................................................... 6 List of Acronyms & Abbreviations ..................................................................................... 7 List of Definitions ................................................................................................................ 9 Summary ............................................................................................................................. 10 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. -

Honors Fellows - Spring 2019

Honors Fellows - Spring 2019 Maya Aboutanos (Dr. Katherine Johnson) Public Health Investigating the Relationship between Spirituality and Health: A Case Study on a Holistic Health Care Facility in North Carolina’s Piedmont Region Betsy Albritton (Dr. Christopher Leupold) Psychology Construction of an Assessment Center for Entry-Level Professionals Serena Archer (Dr. Tony Weaver) Sport Management A Qualitative Analysis of the Intersectional Socialization of NCCAA Division I Student-Athletes Across Diverse Identities Jenna Bayer (Dr. Brian Lyons) Human Resource Reexamining the Demand for Human Resource Certification in Management/Marketing the United States Judah Brown (Dr. Brandon Sheridan) Economics The Impact of National Anthem Protests on National Football League Television Ratings Anna Cosentino (Dr. Derek Lackaff) Media Analytics Using Geolocated Twitter Sentiment to Advise Municipal Decision Making Michael Dryzer (Dr. Scott Wolter) Biophysics Sustainable Sanitation in the Developing World: Deactivating Parasitic Worm Eggs in Wastewater using Electroporation Natalie Falcara (Dr. Christopher Harris) Finance The Financial Valuation of Collegiate Athletics: How Does a Successful Season and Gender of the Sport Impact Financial Donations? Josh Ferno (Dr. Jason Husser) Policy Studies/Sociology What Drives Support for Self-Driving Cars? Evidence from a Survey-Based Experiment Honors Fellows - Spring 2019 Jennifer Finkelstein (Dr. Buffie Longmire-Avital) Public Health/Psychology She Does Not Want Me to Be Like Her: Eating Pathology Risk in Black Collegiate Women and the Role of Maternal Communication Becca Foley (Dr. Barbara Gaither) Strategic Communications/ Exploring Alignment between Stated Corporate Values and Spanish Corporate Advocacy on Environmental and Social Issues Joel Green (Dr. Ariela Marcus-Sells) Religious Studies From American Apocalypse to American Medina: Black Muslim Theological Responses to Racial Injustice in the United States Selina Guevara (Dr. -

Eugenics, Biopolitics, and the Challenge of the Techno-Human Condition

Nathan VAN CAMP Redesigning Life The emerging development of genetic enhancement technologies has recently become the focus of a public and philosophical debate between proponents and opponents of a liberal eugenics – that is, the use of Eugenics, Biopolitics, and the Challenge these technologies without any overall direction or governmental control. Inspired by Foucault’s, Agamben’s of the Techno-Human Condition and Esposito’s writings about biopower and biopolitics, Life Redesigning the author sees both positions as equally problematic, as both presuppose the existence of a stable, autonomous subject capable of making decisions concerning the future of human nature, while in the age of genetic technology the nature of this subjectivity shall be less an origin than an effect of such decisions. Bringing together a biopolitical critique of the way this controversial issue has been dealt with in liberal moral and political philosophy with a philosophical analysis of the nature of and the relation between life, politics, and technology, the author sets out to outline the contours of a more responsible engagement with genetic technologies based on the idea that technology is an intrinsic condition of humanity. Nathan VAN CAMP Nathan VAN Philosophy Philosophy Nathan Van Camp is postdoctoral researcher at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. He focuses on continental philosophy, political theory, biopolitics, and critical theory. & Politics ISBN 978-2-87574-281-0 Philosophie & Politique 27 www.peterlang.com P.I.E. Peter Lang Nathan VAN CAMP Redesigning Life The emerging development of genetic enhancement technologies has recently become the focus of a public and philosophical debate between proponents and opponents of a liberal eugenics – that is, the use of Eugenics, Biopolitics, and the Challenge these technologies without any overall direction or governmental control. -

Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: an Australian Perspective

Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: An Australian Perspective Author Hallam, Adrienne Louise Published 2003 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School School of Science DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/1495 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/367541 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Globalisation, Human Genomic Research and the Shaping of Health: An Australian Perspective Adrienne Louise Hallam B.Com, BSc (Hons) School of Science, Griffith University Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2002 Abstract This thesis examines one of the premier “big science” projects of the contemporary era ⎯ the globalised genetic mapping and sequencing initiative known as the Human Genome Project (HGP), and how Australia has responded to it. The study focuses on the relationship between the HGP, the biomedical model of health, and globalisation. It seeks to examine the ways in which the HGP shapes ways of thinking about health; the influence globalisation has on this process; and the implications of this for smaller nations such as Australia. Adopting a critical perspective grounded in political economy, the study provides a largely structuralist analysis of the emergent health context of the HGP. This perspective, which embraces an insightful nexus drawn from the literature on biomedicine, globalisation and the HGP, offers much utility by which to explore the basis of biomedical dominance, in particular, whether it is biomedicine’s links to the capitalist infrastructure, or its inherent efficacy and efficiency, that sustains the biomedical paradigm over “other” or non-biomedical health approaches. -

Jewels in the Crown

Jewels in the crown CSHL’s 8 Nobel laureates Eight scientists who have worked at Cold Max Delbrück and Salvador Luria Spring Harbor Laboratory over its first 125 years have earned the ultimate Beginning in 1941, two scientists, both refugees of European honor, the Nobel Prize for Physiology fascism, began spending their summers doing research at Cold or Medicine. Some have been full- Spring Harbor. In this idyllic setting, the pair—who had full-time time faculty members; others came appointments elsewhere—explored the deep mystery of genetics to the Lab to do summer research by exploiting the simplicity of tiny viruses called bacteriophages, or a postdoctoral fellowship. Two, or phages, which infect bacteria. Max Delbrück and Salvador who performed experiments at Luria, original protagonists in what came to be called the Phage the Lab as part of the historic Group, were at the center of a movement whose members made Phage Group, later served as seminal discoveries that launched the revolutionary field of mo- Directors. lecular genetics. Their distinctive math- and physics-oriented ap- Peter Tarr proach to biology, partly a reflection of Delbrück’s physics train- ing, was propagated far and wide via the famous Phage Course that Delbrück first taught in 1945. The famous Luria-Delbrück experiment of 1943 showed that genetic mutations occur ran- domly in bacteria, not necessarily in response to selection. The pair also showed that resistance was a heritable trait in the tiny organisms. Delbrück and Luria, along with Alfred Hershey, were awarded a Nobel Prize in 1969 “for their discoveries concerning the replication mechanism and the genetic structure of viruses.” Barbara McClintock Alfred Hershey Today we know that “jumping genes”—transposable elements (TEs)—are littered everywhere, like so much Alfred Hershey first came to Cold Spring Harbor to participate in Phage Group wreckage, in the chromosomes of every organism. -

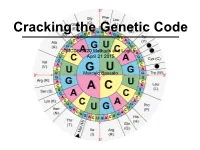

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

STUDY on RISK ASSESSMENT: APPLICATION of ANNEX I of DECISION CP 9/13 to LIVING MODIFIED FISH Note by the Executive Secretary INTRODUCTION 1

CBD Distr. GENERAL CBD/CP/RA/AHTEG/2020/1/3 19 February 2020 ENGLISH ONLY AD HOC TECHNICAL EXPERT GROUP ON RISK ASSESSMENT AND RISK MANAGEMENT Montreal, Canada, 31 March to 3 April 2020 Item 3 of the provisional agenda* STUDY ON RISK ASSESSMENT: APPLICATION OF ANNEX I OF DECISION CP 9/13 TO LIVING MODIFIED FISH Note by the Executive Secretary INTRODUCTION 1. In decision CP-9/13, the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety decided to establish the Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group (AHTEG) on Risk Assessment and Risk Management, which would work in accordance with the terms of reference contained in annex II to that decision. In the same decision, the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Protocol requested the Executive Secretary to commission a study informing the application of annex I of the decision to (a) living modified organisms containing engineered gene drives and (b) living modified fish and present it to the online forum and the AHTEG. 2. Pursuant to the above, and with the financial support of the Government of the Netherlands, the Secretariat commissioned a study informing the application of annex I to living modified fish to facilitate the process referred to in paragraph 6 of decision CP-9/13. The study was presented to the Open-Ended Online Forum on Risk Assessment and Risk Management, which was held from 20 January to 1 February 2020, during which registered participants provided feedback and comments.1 3. -

Genetically Engineered Fish: an Unnecessary Risk to the Environment, Public Health and Fishing Communities

Issue brief Genetically engineered fish: An unnecessary risk to the environment, public health and fishing communities On November 19, 2015, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration announced its approval of the “AquAdvantage Salmon,” an Atlantic salmon that has been genetically engineered to supposedly be faster-growing than other farmed salmon. This is the first-ever genetically engineered animal allowed to enter the food supply by any regulatory agency in the world. At least 35 other species of genetically engineered fish are currently under development, including trout, tilapia, striped bass, flounder and other salmon species — all modified with genes from a variety of organisms, including other fish, coral, mice, bacteria and even humans.1 The FDA’s decision on the AquAdvantage genetically engineered salmon sets a precedent and could open the floodgates for other genetically engineered fish and animals (including cows, pigs and chickens) to enter the U.S. market. Genetically engineered salmon approved by FDA Despite insufficient food safety or environmental studies, the FDA announced its approval of the AquAdvantage Salmon, a genetically engineered Atlantic salmon produced by AquaBounty Technologies. The company originally submitted its application to the FDA in 2001 and the FDA announced in the summer of 2010 it was considering approval of this genetically engineered fish — the first genetically engineered animal intended for human consumption. In December 2012, the FDA released its draft Environmental Assessment of this genetically engineered salmon, and approved it in November 2015. This approval was made despite the 1.8 million people who sent letters to FDA opposing approval of the so-called “frankenfish,” and the 75 percent of respondents to a New York Times poll who said they would not eat genetically engineered salmon.2 The FDA said it would probably not require labeling of the fish; however Alaska, a top wild salmon producer, requires labeling of genetically engineered salmon and momentum is growing for GMO labeling in a number of states across the U.S.