Karen Commitment. Proceedings of a Conference of Indigenous Livestock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Transition of Dressing by the Karamojong People of North Eastern Uganda

University of applied Arts Vienna Art Pedagogic/ Textile-Design and Fine Arts Education Studies THESIS TO OBTAIN MA MASTER OF ARTS (Art and Education) Textile Design and Fine Arts DOCUMENTATION HISTORICAL TRANSITION OF DRESSING BY THE KARAMOJONG PEOPLE OF NORTH EASTERN UGANDA Author: Agnes Achola Matrikelnr.: 09949625 Supervisor: ao. Univ.-Prof. Mag. art. Dr. phil. Marion Elias Location: Wien HISTORICAL TRANSITION OF DRESSING BY THE KARAMOJONG PEOPLE OF NORTH EASTERN UGANDA Agnes Achola TABLE OF CONTENTS I. ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................. 4 1. Objective .................................................................................................................................. 4 2. Research questions ................................................................................................................... 5 II. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ........................................................................................................... 6 III. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 7 IV. HISTORY OF KARAMOJONG .................................................................................................. 9 V. KARAMOJONG CULTURE ...................................................................................................... 10 1. Social Organization ............................................................................................................... -

Comparison of Growth Performance and Meat Quality Traits of Commercial Cross-Bred Pig Versus Large Black Pig Breeds

Comparison of Growth Performance and Meat Quality Traits of Commercial Cross-bred Pig versus Large Black Pig Breeds Yongjie Wang University of Arkansas Fayetteville Keshari Thakali University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Palika Morse University of Arkansas Fayetteville Sarah Shelby University of Arkansas Fayetteville Jinglong Chen Nanjing Agricultural University Jason Apple Texas A&M University Kingsville Yan Huang ( [email protected] ) Texas A&M University https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9464-6889 Research Keywords: Commercial cross-bred pigs, British Large Black pigs, Meat quality, Breeds, Intramuscular fat, RNA-seq, Gene expression Posted Date: November 9th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-101176/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published at Animals on January 15th, 2021. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010200. 1 Comparison of Growth Performance and Meat Quality Traits of Commercial Cross-bred Pig 2 versus Large Black Pig Breeds 3 Yongjie Wang1, Keshari Thakali2, Palika Morse1, Sarah Shelby1, Jinglong Chen3, Jason Apple4, 4 and Yan Huang1, * 5 1. Department of Animal Science, Division of Agriculture, University of Arkansas, 6 Fayetteville, Arkansas 7 2. Arkansas Children’s Nutrition Center & Department of Pediatrics, University of Arkansas 8 for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, Arkansas 9 3. Key Laboratory of Animal Physiology & Biochemistry, College of Veterinary Medicine, 10 Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China 11 4. Department of Animal Science and Veterinary Technology, Texas A&M University, 12 Kingsville, TX 78363 13 *. Corresponding email: [email protected] 14 Declarations of interest: none 15 16 Abstract 17 Background: The meat quality of different pig breeds is associated with their different muscle tissue 18 physiological processes, which involves a large variety of genes related with muscle fat and energy 19 metabolism. -

Animal Genetic Resources Information Bulletin

The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Les appellations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’alimentation et l’agriculture aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. Las denominaciones empleadas en esta publicación y la forma en que aparecen presentados los datos que contiene no implican de parte de la Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y la Alimentación juicio alguno sobre la condición jurídica de países, territorios, ciudades o zonas, o de sus autoridades, ni respecto de la delimitación de sus fronteras o límites. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and the extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, Information Division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Viale delle Terme di Caracalla, 00100 Rome, Italy. Tous droits réservés. Aucune partie de cette publication ne peut être reproduite, mise en mémoire dans un système de recherche documentaire ni transmise sous quelque forme ou par quelque procédé que ce soit: électronique, mécanique, par photocopie ou autre, sans autorisation préalable du détenteur des droits d’auteur. -

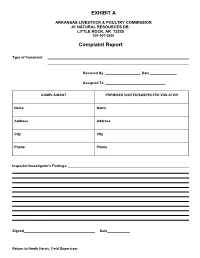

Complaint Report

EXHIBIT A ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK & POULTRY COMMISSION #1 NATURAL RESOURCES DR. LITTLE ROCK, AR 72205 501-907-2400 Complaint Report Type of Complaint Received By Date Assigned To COMPLAINANT PREMISES VISITED/SUSPECTED VIOLATOR Name Name Address Address City City Phone Phone Inspector/Investigator's Findings: Signed Date Return to Heath Harris, Field Supervisor DP-7/DP-46 SPECIAL MATERIALS & MARKETPLACE SAMPLE REPORT ARKANSAS STATE PLANT BOARD Pesticide Division #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 Insp. # Case # Lab # DATE: Sampled: Received: Reported: Sampled At Address GPS Coordinates: N W This block to be used for Marketplace Samples only Manufacturer Address City/State/Zip Brand Name: EPA Reg. #: EPA Est. #: Lot #: Container Type: # on Hand Wt./Size #Sampled Circle appropriate description: [Non-Slurry Liquid] [Slurry Liquid] [Dust] [Granular] [Other] Other Sample Soil Vegetation (describe) Description: (Place check in Water Clothing (describe) appropriate square) Use Dilution Other (describe) Formulation Dilution Rate as mixed Analysis Requested: (Use common pesticide name) Guarantee in Tank (if use dilution) Chain of Custody Date Received by (Received for Lab) Inspector Name Inspector (Print) Signature Check box if Dealer desires copy of completed analysis 9 ARKANSAS LIVESTOCK AND POULTRY COMMISSION #1 Natural Resources Drive Little Rock, Arkansas 72205 (501) 225-1598 REPORT ON FLEA MARKETS OR SALES CHECKED Poultry to be tested for pullorum typhoid are: exotic chickens, upland birds (chickens, pheasants, pea fowl, and backyard chickens). Must be identified with a leg band, wing band, or tattoo. Exemptions are those from a certified free NPIP flock or 90-day certificate test for pullorum typhoid. Water fowl need not test for pullorum typhoid unless they originate from out of state. -

Pdf Grade 11 Agriculture Science Week 4

01/10/2020 Review questions 1. Explain how man has come to domesticate swine for commercial production. 2. Why is pigs considered an omnivorous animal. 3. State three causes of dystocia in swine. 4. Why is flushing necessary for sows. 5. List three breeds of swine that are reared in your community. References Book R. Ramharacksingh, 2011. Agricultural science for C.S.E.C examination macmillan publishers s. Ragoonanan,2011. Agriculture for C.S.E.C revision course. Caribbean educational publishers. T. De Ponti“, the crop yield gap between organic and conventional agriculture" in agricultural systems. Internet Https://en.Wikipedia.Org/wiki/pig Https://www.Pork.Org/facts/pork-bytes/everything-but-the-oink/ Video link https://www.Youtube.Com/watch?V=3936xfp7xu0 Https://www.Youtube.Com/watch?V=uru_-um4n2m&list=pl45yzabyqusb--wvcfcw-q5ftazixpnwv&index=5 MINISTRY OF EDUCATION SECONDARY ENGAGEMENT PROGRAMME OCTOBER 2020 WEEK 4 LESSON # 2 GRADE :11 Subject : Agricultural Science Topic : Swine production: Sub Topic : Breeds and types of swine. Objective To recognize the characteristics of each breed of swine. 31 01/10/2020 Breeds of Swine Some of the main breeds Berkshire - Originating in Britain in the mid-1500’s. The Berkshire is prized for its juiciness, flavor and tenderness. The Berkshire is a black pig that can have white on the legs, ears, tail and face. It yields a pink-hued, heavily marbled meat whose high fat content is suitable for long cooking times and high-temperature cooking. Chester White - The Chester White originated in Chester County, PA in the early 1800’s when strains of large, white pigs common to the Northeast United States were bred with a white boar imported from Bedfordshire, England. -

Pigs Class: P0001/0525 Boar, Born in 2018

Pig Section Results - 2019 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/0525 BOAR, BORN IN 2018 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A Newth, Shepton Mallet, Somerset (2) Prestcombe Merry 9 2 Mr J Kingdon, Newquay, Cornwall (1) Warburton Obertus 2 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/0526 BOAR BORN IN 2019 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A Newth, Shepton Mallet, Somerset (4) Prestcombe Merry 2 Mr J Kingdon, Newquay, Cornwall (3) Middlelanherne Zenk 1237 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/0527 SOW OR GILT BORN BEFORE 1 JULY 2018 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Mr J Kingdon, Newquay, Cornwall (5) Middlelanherne Pauline 1190 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/0528 GILT BORN IN 2018, ON OR AFTER 1 JULY. Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A Newth, Shepton Mallet, Somerset (10) Prestcombe Rosi 2 2 Miss A Newth, Shepton Mallet, Somerset (9) Prestcombe Pauline 8 3 Mr D & Miss S Pawson, Doncaster, South Yorkshire (11) Warburton Pauline 3 4 Mr G & Mrs A Pawson, Manchester, (13) Warburton Pauline 6 7 Mr J Kingdon, Newquay, Cornwall (6) Middlelanherne Pauline 1234 ROYAL CORNWALL SHOW 2019 - PIG SECTION RESULTS 17 June 2019 Page 1 of 29 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/0529 GILT BORN IN 2019 Placing Exhibitor Catalogue No. Livestock Name 1 Miss A Newth, Shepton Mallet, Somerset (15) Prestcombe Rosi 2 Mr G & Mrs A Pawson, Manchester, (17) Warburton Pauline 7 3 Mr J Kingdon, Newquay, Cornwall (14) Middlelanherne Pauline 1242 4 Mr G & Mrs A Pawson, Manchester, (18) Warburton Pauline 8 SECTION: PIETRAIN PIGS CLASS: P0001/A761 A SPECIAL PRIZE OF ROSETTES ARE OFFERED BY THE R.C.A.A. -

Decentralization and the Situation of Selected Ethnic and Racial Minorities

DECENTRALIZATION AND THE SITUATION OF SELECTED ETHNIC AND RACIAL MINORITIES: A HUMAN RIGHT AUDIT ROSE NAKAYI Copyright Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2007 ISBN 9970-511-13-6 HURIPEC Working Paper No. 15 July, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.............................................................................ii SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS.........................iii LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS......................................................v I.INTRODUCTION............................................................................1 1.1 The Scope of the Study...............................................................2 1.2 Minorities: A general overview...................................................3 II. ETHNIC AND RACIAL GROUPS IN UGANDA....................................8 2.1 Facts and Figures.......................................................................8 2.2 Placing Ethnicity in Context.......................................................11 III. LEFT OUT? THE CASE OF UGANDAN ASIANS.............................13 3.1 Historical background..............................................................13 3.2 A Contested Citizenship...............................................................15 3.3 Decentralization and the Question of Ugandan Asians.............16 IV. THE BARULI-BANYALA QUESTION...............................................20 4.1 A Historical Prelude..................................................................20 4.2 The Baruli-Banyala in Kayunga District.....................................20 -

Pastoralism As a Conservation Strategy

PASTORALISM AS A CONSERVATION STRATEGY UGANDA COUNTY PAPER Prepared for IUCN Study By Margaret A. Rugadya Associates for Development Kampala CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES ....................................................................................... iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ iv 1 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1.1 Indigenous versus Modern ........................................................................................... 1 1.1.2 The Review ................................................................................................................ 3 1.2 Country Context: Uganda .............................................................................................. 5 1.2.1 Pastoral Lands and Zones ......................................................................................... 6 1.2.2 Vegetation and Land Use .......................................................................................... 9 2. NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT .................................................................. 12 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 12 2.2 Strategies for Resource Management -

Utilization of Frozen Thawed Semen in Large Black Pigs

UTILIZATION OF FROZEN THAWED SEMEN IN LARGE BLACK PIGS; GROWTH AND CARCASS CHARACTERISTICS OF LARGE BLACK PIGS FED DIETS SUPPLEMENTED WITH OR WITHOUT ALFALFA by Katharine Grace Sharp A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Department of Animal Sciences West Lafayette, Indiana August 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Kara Stewart, Chair Department of Animal Science Dr. Brian Richert Department of Animal Science Dr. Brad Kim Department of Animal Science Dr. Zoltan Machaty Department of Animal Science Approved by: Dr. Alan G. Mathew 2 Dedicated to my Aunt Eunice (1925-2020) 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Kara Stewart for giving me the opportunity to pursue a Master’s degree, and to do research in an area of agriculture that will help small pork producers and more importantly assist the pigs found on small farms. I would like to thank Dr. Stewart for her guidance and knowledge during this project and for her patience helping me develop as a student, and researcher. I would like to thank my committee, Dr. Brad Kim, Dr. Zoltan Machaty, and Dr. Brian Richert for providing support and knowledge helping me improve. Many thanks to Dr. Richert for teaching me about finishing swine, and for formulating the finishing diets. I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Harvey Blackburn for funding this project, for your advice the past two years and helping me. Thank you to Dr. Charlene Couch for her passion for these special pigs, and for teaching me to how to connect with the breeders. -

Snomed Ct Dicom Subset of January 2017 Release of Snomed Ct International Edition

SNOMED CT DICOM SUBSET OF JANUARY 2017 RELEASE OF SNOMED CT INTERNATIONAL EDITION EXHIBIT A: SNOMED CT DICOM SUBSET VERSION 1. -

Livestock Classes Prize Schedule

SCHEDULE SPONSOR CLOSING DATE FOR ENTRIES April 17th LIVESTOCK CLASSES PRIZE SCHEDULE ENTER ONLINE: WWW.RCSENTRIES.CO.UK | TELEPHONE: 01208 812183 HOSTING COMPETITIONS FOR ALPACAS - ANGORA GOATS - CATTLE - SHEEP PIGS - DAIRY GOATS - DONKEYS SHEARING - LIVE LAMB - YFC Visit our website to see our full range of classes and to enter online w w w . d e v o n c o u n t y s h o w . c o . u k CONTENTS PAGE Bye-Laws and Regulations ...................................................................................................................................................... 59 Privacy Policy ............................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Entry Fees ................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Sponsorship ................................................................................................................................................................................ 6 Membership Application Form .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Provisional Judging Time Tables .............................................................................................................................................. 9 Regulations Cattle ....................................................................................................................................................................................... -

UGANDA COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

UGANDA COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 20 April 2011 UGANDA DATE Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN UGANDA FROM 3 FEBRUARY TO 20 APRIL 2011 Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON UGANDA PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 3 FEBRUARY AND 20 APRIL 2011 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Map ........................................................................................................................ 1.06 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Political developments: 1962 – early 2011 ......................................................... 3.01 Conflict with Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA): 1986 to 2010.............................. 3.07 Amnesty for rebels (Including LRA combatants) .............................................. 3.09 4. RECENT DEVELOPMENTS ........................................................................................... 4.01 Kampala bombings July 2010 ............................................................................. 4.01 5. CONSTITUTION.......................................................................................................... 5.01 6. POLITICAL SYSTEM ..................................................................................................