Cowboy Culture Sermon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liubov Teplova Reader's Guide to RESTLESS by William Boyd

Liubov Teplova Reader’s Guide to RESTLESS by William Boyd ББК 81.2 Англ. УДК 802.0 Т34 Рецензенты: Самойленко Наталия Борисовна – кандидат педагогических наук, доцент кафедры иностранной филологии Севастопольского городского гуманитарного университета Майборода Алексей Анатольевич – кандидат филологических наук, доцент кафедры иностранной филологии и методики преподавания РВУЗ «Крымский гуманитарный университет» (г. Ялта) Печатается по решению Методического совета Филиала Московского государственного университета имени М.В. Ломоносова в г. Севастополе Протокол № 5 от 18.04.2013 Теплова Л.И. Reader’s Guide to “Restless” by William Boyd: учебное пособие. – Севастополь: РИБЭСТ, 2013 – 142 .с. Данное учебное пособие представляет собой сборник заданий и упражнений к роману современного английского писателя Уильяма Бойда RESTLESS. Пособие содержит 14 разделов (согласно количеству глав в романе), в каждом из которых представлены по два блока заданий, нацеленных на проверку понимания фактического содержания и правильности извлечения информации (Comprehension Tasks), а также на понимание языковых явлений и снятие языковых трудностей (Language Focus). Выполнение заданий блока Comprehension Tasks в ряде случаев предполагает не только работу с текстом романа, но также и привлечение дополнительных источников линвгострановедческой информации. Пособие предназначено для лиц, изучающих английский язык как иностранный, и достигших уровня владения не ниже B 1 по CEFR и может быть использовано при обучении носителей разных языков. Отдельный раздел посвящен -

Lnußi[?| Tn 'IT STARTED with EVE.' Kay Kyter, and Loy M “SHADOW of the •TANKS MILLION.” James Oleaaon

Monday, March SO, 1942 DETROIT EVENING TIMES (PHONE CHERRY MfOO) PAGE 7 to of quartermaster or possibly which he would like to serve and pencil, shaving soap, toilet that he Is deemed unauitsble for in Illinois and had planned b# Service Briefs Fighting Men's Friend socks, military necessary boatsswain’s mate or boatswain. If there are vacancies and he can water, handkerchief* and Active nervier. married. Is a blood teat very LIBERTY LIMERICKS time you would be be spared from his own outfit, the like are acceptable. • Mrs. J. Barnes. Q—l was bom Illinois? What are the require- _ At the same in ¦ . might be approved. entitled to all the privileges and the transfer Worried. Q—ls a man Is wanted in Poland and at the at*e of 5 ments to obtain a marriage license T protection way of insur- in another state for a felony and years came to the United States in the GIFTS FOR SOLDIF.R \—You must take • blood ance, etc., afforded men in the is called into service in the army, with my parents. In June, I Michigan a brother In but certificate from w Wife Sister. —l have Am a Man Job for regular Q would the government turn him married an American citizen. timt. navy or any other branch of the country's armed forces. the marines of whom we are all over to the state in which he is 1 an American citizen? reputable physician In Michigan wanted? your father out his by the Illinois WANTS TRANSFER very proud. -

Frame by Frame

FRAME BY FRAME by Glen Ryan Tadych As we celebrate Thanksgiving and prepare Watching it as an adult though is a different experi- ences go, “What is this?!” And while this factor is for the holiday season, some of cinema’s most ence sure enough, as I’m able to understand how what made Toy Story memorable to most audiences Lasseter’s work on the short film and other TGG anticipated films prepare to hit theaters, most the adult themes are actually what make the film so upon leaving the theater, the heart of the film still projects landed him a full-time position as an notably Star Wars: The Force Awakens. This moving. lies beneath the animation, the impact of which is interface designer that year. However, everything past Wednesday, Disney and Pixar’s latest what makes Toy Story a classic. changed for TGG in 1986. computer-animated adventure, The Good Today, I see Toy Story as the Star Wars (1977) of Dinosaur, released nationwide to generally my generation, and not just because it was a “first” Toy Story’s legacy really begins with Pixar’s be- Despite TGG’s success in harnessing computer positive reception, but this week also marked for the film industry or a huge critical and commer- ginnings in the 1980s. Pixar’s story begins long be- graphics, and putting them to use in sequences another significant event in Pixar history: the cial success. Like Star Wars, audiences of all ages fore the days of Sheriff Woody and Buzz Lightyear, such as the stained-glass knight in Young Sherlock 20th anniversary of Toy Story’s original theatri- worldwide enjoyed and cherished Toy Story because and believe it or not, the individual truly responsible Holmes (1985), Lucasfilm was suffering financially. -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. On the Cover: “Splash!”, photo by Tim Devine Issue 24 Taking the Plunge on 42 Contents Splash Mountain Letters ..........................................................................................6 Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News & Updates................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic O Canada by Tim Foster............................................................................16 50 Explorer Emporium by Lou Mongello .....................................................................18 Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett .....................................................................20 Photography Tips & Tricks by Tim Devine .........................................................................22 Music in the Parks Pin Trading & Collecting by John Rick .............................................................................24 -

Toy Story Crafts Website

CCRRAAFFTT CCOORRRRAALL:: TTOOYY SSTTOORRYY EEDDIITTIIOONN Yee haw! These three crafts are inspired by Toy Story, because Jessie the Cowgirl is a Patsy Montana Award Winner! The award is named after Cowgirl Honoree Patsy Montana, who was the first woman to sell a million records with her song, “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart.” Jessie the Cowgirl continues to entertain others through the tradition of the cowgirl. We will be making three crafts: a pipe cleaner snake based on Sheriff Woody’s signature line, “There’s a snake in my boot,” a slinky dog paper chain, and a Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head paper doll. MATERIALS: PIPE CLEANER SNAKE Pipe Cleaner Googly Eyes Beads Hot glue or glue MATERIALS: SLINKY DOG PAPER CHAIN White, brown, and Googly eyes black construction paper Stapler or glue Scissors M ATERIALS: MR. POTATO HEAD PAPER DOLL Construction paper Optional: Googly Scissors eyes, fabric, tissue Glue paper. PPIIPPEE CCLLEEAANNEERR SSNNAAKKEE 1. Take one pipe 2. Start to string cleaner and twist the beads on the pipe end so that beads cleaner. Make a cannot fall off the pattern or make it pipe cleaner. random! 3. After putting 4. Twist the pipe beads on the pipe cleaner back into cleaner, leave 3 the last bead on inches of pipe the pipe cleaner to cleaner free. create a loop. This is the face of the snake. 5. Put two beads of hot glue on either side of the face. Place the googly eyes down on the hot glue beads. Your snake is complete! SSLLIINNKKYY DDOOGG PPAAPPEERR CCHHAAIINN 1.Cut a dark brown strip 2. -

DURBIN CROSSING CHRONICLE July 2019

DURBIN CROSSING CHRONICLE July 2019 Durbin Crossing Chronicle | July 2019 Inside This Issue: Contact Listing Did you know?? Pond Press Stay Connected Durbin Interest Groups 4th of July Safety Pet Safety Summer Safety Chick-fil-A / Food Trucks Upcoming Events Independence Day Celebration Wall of Heroes Magic Show Pool Movie Tasty Dog for Dinner Poolside Trivia Craft Night Blood Drive FREE Skin Cancer Screenings Kids Korner Wild Wonders Chess Camp As we celebrate our Nation’s freedom, we honor Kindergarten Krafts the courageous men and women Back to School Bash Coming Soon dedicated to preserving it! Mary Time Summer Program Mary’s Summer Arts Camp Have a SAFE and HAPPY 4th of JULY! Pool Information Swim Lesson Information Swim Team Information Sunrise / Sunset Calendar DURBIN CROSSING HOA MEETING Pool Policies Thunder Policy The next meeting of the Master HOA Board Sports & Fitness will be held on Tuesday, July 16th, 6:00pm TaiChi Workshop Aqua Fitness / Zumba at the South Social Hall. Amenity Soccer Darryl Anderson, HOA Property Manager, [email protected] North / South calendars Ad Program / Advertising www.durbincrossingliving.com 1 Durbin Crossing Community Contact List Our next Amenity Staff: General Manager scheduled CDD Margaret Alfano meeting is [email protected] Monday, Field Operations Manager Steve Howell July 22, 2019 [email protected] at 6pm, Amenities Manager in the South Danelle DeMarco [email protected] Social Hall. [email protected] / 904-230-2011 HOA Property Manager CDD District Manager Floridian Property Management Governmental Management Services Darryl Anderson Daniel Laughlin [email protected] [email protected] 904-592-4090 904-940-5850 ext. -

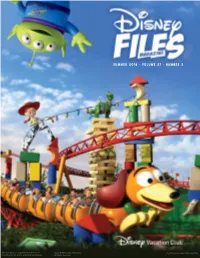

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2

Summer 2018 • Volume 27 • Number 2 Slinky® Dog is a registered trademark of Jenga® Pokonobe Associates. Toy Story characters ©Disney/Pixar Poof-Slinky, Inc. and is used with permission. All rights reserved. WeLcOmE HoMe Leaving a Disney Store stock room with a Buzz Lightyear doll in 1995 was like jumping into a shark tank with a wounded seal.* The underestimated success of a computer-animated film from an upstart studio had turned plastic space rangers into the hottest commodities since kids were born in a cabbage patch, and Disney Store Cast Members found themselves on the front line of a conflict between scarce supply and overwhelming demand. One moment, you think you’re about to make a kid’s Christmas dream come true. The next, gift givers become credit card-wielding wildebeest…and you’re the cliffhanging Mufasa. I was one of those battle-scarred, cardigan-clad Cast Members that holiday season, doing my time at a suburban-Atlanta mall where I developed a nervous tick that still flares up when I smell a food court, see an astronaut or hear the voice of Tim Allen. While the supply of Buzz Lightyear toys has changed considerably over these past 20-plus years, the demand for all things Toy Story remains as strong as a procrastinator’s grip on Christmas Eve. Today, with Toy Story now a trilogy and a fourth film in production, Andy’s toys continue to find new homes at Disney Parks around the world, including new Toy Story-themed lands at Disney’s Hollywood Studios (pages 3-4) and Shanghai Disneyland (page 22). -

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science

SHSU Video Archive Basic Inventory List Department of Library Science A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Hitmakers: The Teens Who Stole Pop Music. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume One – Dionne Warwick: Don’t Make Me Over. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – Bobby Darin. c2001. A & E: The Songmakers Collection, Volume Two – [1] Leiber & Stoller; [2] Burt Bacharach. c2001. A & E Top 10. Show #109 – Fads, with commercial blacks. Broadcast 11/18/99. (Weller Grossman Productions) A & E, USA, Channel 13-Houston Segments. Sally Cruikshank cartoon, Jukeboxes, Popular Culture Collection – Jesse Jones Library Abbott & Costello In Hollywood. c1945. ABC News Nightline: John Lennon Murdered; Tuesday, December 9, 1980. (MPI Home Video) ABC News Nightline: Porn Rock; September 14, 1985. Interview with Frank Zappa and Donny Osmond. Abe Lincoln In Illinois. 1939. Raymond Massey, Gene Lockhart, Ruth Gordon. John Ford, director. (Nostalgia Merchant) The Abominable Dr. Phibes. 1971. Vincent Price, Joseph Cotton. Above The Rim. 1994. Duane Martin, Tupac Shakur, Leon. (New Line) Abraham Lincoln. 1930. Walter Huston, Una Merkel. D.W. Griffith, director. (KVC Entertaiment) Absolute Power. 1996. Clint Eastwood, Gene Hackman, Laura Linney. (Castle Rock Entertainment) The Abyss, Part 1 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss, Part 2 [Wide Screen Edition]. 1989. Ed Harris. (20th Century Fox) The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: [1] documentary; [2] scripts. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: scripts; special materials. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – I. The Abyss. 1989. (20th Century Fox) Includes: special features – II. Academy Award Winners: Animated Short Films. -

A Content Analysis of Gender Themes in Full-Length Animated Disney Feature Films

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2000 The Gendered World of Disney: A Content Analysis of Gender Themes in Full-length Animated Disney Feature Films Beth A. Wiersma South Dakota State University Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd Part of the American Film Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Sociology Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wiersma, Beth A., "The Gendered World of Disney: A Content Analysis of Gender Themes in Full-length Animated Disney Feature Films" (2000). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1906. https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/etd/1906 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Gendered World of Disney: A Content Analysis of Gender Themes in Full-Length Animated Disney Feature Films BY Beth A. Wiersma A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillmeni of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Major in Sociology South Dakota State University 2000 11 The Gendered World of Disney: A Content Analysis of Gender Themes in Full-Length Animated Disney Feature Films This dissertation is approved as a creditable and independent investigation by a candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree and is. -

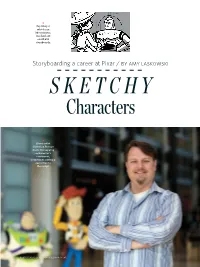

SKETCHY Characters

% Toy Story 3, which ran 103 minutes, was laid out on 49,651 storyboards. Storyboarding a career at Pixar / by Amy Laskowski SKETCHY Characters % Story artist Christian Roman starts by mapping a character’s movement, sometimes adding a gag or two to the script. PHOTOGRAPHS BY DEBORAH COLEMAN/PIXAR † A sequel like Toy Story 3 can be bur- dened with the mis- conception that it will be inferior to the original. Visitors to Pixar’s Emeryville, what movie Roman is currently Calif., campus who hope to catch a storyboarding (based on Pixar’s glimpse of the animation studio’s lineup of films, it could be The next killer project better prepare Good Dinosaurr or Finding Dory, to have their hopes dashed. The among others). Because he wasn’t studio is so secretive about work in allowed to show us his offiffi ce, progress that Bostonia reporters, Roman met with us in the neu- there to interview story artist tral space of a conference room, Christian Roman, were not allowed where several easels were pur- to go anywhere without an escort posely devoid of any hint of on- and were forbidden to discuss going or upcoming work. Summer 2014 BOSTONIA 47 Meanwhile, on the floor below, toys, you need to consider that the out the scenes complete with dialogue, a sun-splashed atrium displays the camera is down at their level,” he says. spoken by the artists. They even sing studio’s past glories, some plated in Drawing is the major part of the songs that accompany the on- 24-karat gold. -

Pixar and Digital Culture Eric Duwayne Herhuth University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2015 Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture Eric DuWayne Herhuth University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Herhuth, Eric DuWayne, "Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1000. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1000 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANIMATING AESTHETICS: PIXAR AND DIGITAL CULTURE by Eric Herhuth A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee August 2015 ABSTRACT ANIMATING AESTHETICS: PIXAR AND DIGITAL CULTURE by Eric Herhuth The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice Petro In the pre-digital age of cinema, animated and live-action film shared a technological basis in photography and they continue to share a basis in digital technology. This fact limits the capacity for technological inquiries to explain the persistent distinction between animated and live-action film, especially when many scholars in film and media studies agree that all moving image media are instances of animation. Understanding the distinction in aesthetic terms, however, illuminates how animation reflexively addresses aesthetic experience and its function within contexts of technological, environmental, and socio-cultural change. “Animating Aesthetics: Pixar and Digital Culture” argues that the aesthetics that perpetuate the idea of animation as a distinct mode in a digital media environment are particularly evident in the films produced by Pixar Animation Studios. -

Schweizer Film = Film Suisse : Offizielles Organ Des Schweiz

Objekttyp: Advertising Zeitschrift: Schweizer Film = Film Suisse : offizielles Organ des Schweiz. Lichtspieltheater-Verbandes, deutsche und italienische Schweiz Band (Jahr): 5 (1939) Heft 76-77 PDF erstellt am: 30.09.2021 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Eos-Film S.A. Bâle Ie' Bloc 1939-1940 D'après le célèbre roman de Nach dem in der Weltwoche Beau Geste P. C. Wren erschienen gleichnamigen avec Roman von P. C. Wren mit Rob. Preston Beau Geste (Beau Geste) Cary Cooper, Ray Milland, Brian Donlevy, Donald O'Connor Un très grand film avec Ein Grofjfilm mit L'auberge de la Jamaïque Charles Laughton Deutscher Titel steht noch nicht fest en tête d'une distribution in der Hauptrolle (Jamaica Inn) de 1er ordre Produktion: Erich Pommer Un film de grande aventure Ein Meisterwerk von Pacific Express un chef d'ceuvre de Cecil B.