Milligan's Passivity During the Civil Rights Movement: Its Theological Roots and the Hopeful Movement Towards an Active Approach to Social Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Stampede Staff Reflect on Past, Speak on Future of Journalism Q&A

Volume 82 No. 2 Milligan College October 20, 2016 www.milliganstampede.com The Stampede Milligan students elect Trump for president Overall, these statistics stack up as fol- Maddie Barnett, Staff Reporter lows: After chapel last Tuesday, The Stam- voting history has been unpredictable pede held a mock election, setting up and competitive. In the 1996 presiden- voting booths at the cafe and the Grill. tial election, for example, President Bill Students were given the option of vot- Clinton won the state by a mere 2.4 per- ing for one of four candidates: Hil- cent of the popular vote over his rival, According to these reports, Trump not lary Clinton (Democrat), Gary John- and President George W. Bush won by only has a substantial lead at Milligan son (Libertarian), Jill Stein (Green) only 3.8 percent in 2000. compared to other candidates but also or Donald Trump (Republican). Of So, how shocking is it that Trump led compared to other, larger populations these choices, the 88 student partici- by 21.6 percent of student votes in this Source: 270toWin in the United States. pants voted overwhelmingly in favor of mock election? As for national polls, an Oct. 14, 2016 Still, there remains a high number of Trump. The answer? Not very. Over the course poll by Rasmussen Reports shows that Clinton (and third party) fans in the of the past few elections, the Republi- Clinton’s support is much higher than country, and the presidential race is can Party has taken a definite hold on reported by the other polls. -

2021-2022 Upper School Profile

2021-2022 UPPER SCHOOL PROFILE Founded in 1958, Asheville Christian Academy is an independent, non-denominational, Accreditation college preparatory Christian day school for young men and women. ACA is accredited Cognia and ACSI Kindergarten to Grade 12. Total enrollment is currently 710 students with 250 enrolled (Association of Christian in the Upper School. Our campus is located in Swannanoa, a valley community just east Schools International) of Asheville, NC and serves families from five counties and two countries. Head of School Our Mission Dr. William G. George Seeking to serve Jesus Christ and uphold his pre-eminence, Asheville Head of Upper Christian Academy, in committed partnership with Christian parents, pro- School vides a Gospel-centered education to shepherd and inspire Christ-oriented Mr. Wade Tapp lives within a community of grace and truth. Director of College Guidance Portrait of a Graduate Mrs. Keri Boer We join our parents in shaping young lives into men and women who follow Christ, learn [email protected] intentionally, restore culture, communicate effectively, and serve and lead. Upper School The Academic Program Enrollment The course of study combines the best of traditional liberal arts and modern form and Grades 9-12 250 content with an authentic Biblical worldview. Teachers and students working together are key to creating a school culture that values excellence, hard work, brotherly love, and Senior Class of 2021: 58 a vision for the future. Our Honor Covenant provides a Christian foundation -

2019-20 NAIA Scholar Teams

Institution Name State Select Sport Team GPA Aquinas CollegeMichigan Volleyball Women's 3.480 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Indoor Track & Field Women's 3.340 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Tennis Women’s 3.410 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Softball 3.350 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Lacrosse Women's 3.280 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Golf Women's 3.310 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Cross Country Women’s 3.490 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Bowling Women's 3.460 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Indoor Track & Field Men's 3.180 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Tennis Men’s 3.540 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Golf Men's 3.310 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Cross Country Men’s 3.420 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Baseball 3.350 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Competitive Dance 3.660 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Competitive Cheer 3.270 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Lacrosse Men's 3.010 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Soccer Women’s 3.380 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Soccer Men’s 3.330 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Basketball Women’s - Division II 3.170 Aquinas CollegeMichigan Basketball Men’s - Division II 3.080 Arizona Christian University Arizona Swimming & Diving Women's 3.690 Arizona Christian University Arizona Cross Country Women’s 3.550 Arizona Christian University Arizona Tennis Women’s 3.550 Arizona Christian University Arizona Baseball 3.490 Arizona Christian University Arizona Outdoor Track & Field Women's 3.450 Arizona Christian University Arizona Cross Country Men’s 3.370 Arizona Christian University Arizona Softball 3.310 Arizona Christian University Arizona Volleyball Men's 3.040 Arizona Christian University Arizona Swimming & Diving Men's -

Member Colleges & Universities

Bringing Colleges & Students Together SAGESholars® Member Colleges & Universities It Is Our Privilege To Partner With 427 Private Colleges & Universities April 2nd, 2021 Alabama Emmanuel College Huntington University Maryland Institute College of Art Faulkner University Morris Brown Indiana Institute of Technology Mount St. Mary’s University Stillman College Oglethorpe University Indiana Wesleyan University Stevenson University Arizona Point University Manchester University Washington Adventist University Benedictine University at Mesa Reinhardt University Marian University Massachusetts Embry-Riddle Aeronautical Savannah College of Art & Design Oakland City University Anna Maria College University - AZ Shorter University Saint Mary’s College Bentley University Grand Canyon University Toccoa Falls College Saint Mary-of-the-Woods College Clark University Prescott College Wesleyan College Taylor University Dean College Arkansas Young Harris College Trine University Eastern Nazarene College Harding University Hawaii University of Evansville Endicott College Lyon College Chaminade University of Honolulu University of Indianapolis Gordon College Ouachita Baptist University Idaho Valparaiso University Lasell University University of the Ozarks Northwest Nazarene University Wabash College Nichols College California Illinois Iowa Northeast Maritime Institute Alliant International University Benedictine University Briar Cliff University Springfield College Azusa Pacific University Blackburn College Buena Vista University Suffolk University California -

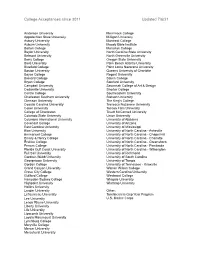

College Acceptances Since 2011 Updated 7/6/21

College Acceptances since 2011 Updated 7/6/21 Anderson University Merrimack College Appalachian State University Milligan University Asbury University Montreat College Auburn University Moody Bible Institute Barton College Moravian College Baylor University North Carolina State University Belmont University North Greenville University Berry College Oregon State University Biola University Palm Beach Atlantic University Bluefield College Point Loma Nazarene University Boston University Queens University of Charlotte Boyce College Regent University Brevard College Salem College Bryan College Samford University Campbell University Savannah College of Art & Design Cedarville University Shorter College Centre College Southeastern University Charleston Southern University Stetson University Clemson University The King’s College Coastal Carolina University Trevecca Nazarene University Coker University Toccoa Falls University College of Charleston Truett McConnell University Colorado State University Union University Columbia International University University of Alabama Covenant College University of Arizona East Carolina University University of Mississippi Elon University University of North Carolina - Asheville Emmanuel College University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill Emory & Henry College University of North Carolina - Charlotte Erskine College University of North Carolina - Greensboro Ferrum College University of North Carolina - Pembroke Florida Gulf Coast University University of North Carolina - Wilmington Full Sail University University -

2021 National Convention Program

National Council of Alpha Chi 2017-21 At-Large Faculty Members Bonita Cade, Roger Williams University (VI) ........................................................................................2013 -17, 2017-21 David Jones, Westminster College, Missouri (IV) ............................. (Reg. IV S-T 2000-12) 2009-13, 2013-17, 2017-21 Agashi Nwogbaga, Wesley College (VI) .............................................................................................................2017-21 Kathi Vosevich, Lindenwood University (elected when at Shorter U/III but moved to Reg IV 2019) ....................2017-21 2019-23 At-Large Faculty Members Linda Cowan, West Liberty University (V) ...........................................................................................................2019-23 June Hobbs, Gardner-Webb University (III) .........................................................................................2015 -19, 2019-23 Steve Hoekstra, Kansas Wesleyan University (IV) .............................................................................................2019-23 Kip Wheeler, Carson-Newman University (III) ....................................................................................................2019-23 Regional Secretary-Treasurers Region I Karl Havlak, Angelo State University .............................................................2010 -14, 2014-18, 2018-22 Region II E. Kate Stewart, University of Arkansas at Monticello .......................................... (A-L 2011-15) 2020-24 Region III Fabrice -

2020 Annual Report and Proceedings

20 2ANNUAL0 REPORT and Proceedings Table of Contents Message from the Chair of SACSCOC Board of Trustees . 5 Message from the President of SACSCOC . 7 1 Annual Report . 8 Philosophical Statement . 9 Changes to SACSCOC Administrative Staff . 10 Leadership, Service, and Outstanding Chair Award Recipients . 10 SACSCOC Activities . 12 2 Organization of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) and SACSCOC . 14 Officers and Members of the Board of Trustees of SACS . 15 Officers and Standing Committees of SACSCOC College Delegate Assembly . 16 Standing Committees of SACSCOC Board of Trustees . 20 Evaluation Committees of SACSCOC Board of Trustees . 22 Ad Hoc Committees of the SACSCOC Board of Trustees and the College Delegate Assembly . 26 SACSCOC Staff . 30 3 Sessions of the SACSCOC Board of Trustees, the College Delegate Assembly, and the Appeals Committee . 32 Executive Session of SACSCOC Board of Trustees—September 2020 . 33 Executive Session of SACSCOC Board of Trustees—December 2020 . 43 Business Meeting of the College Delegate Assembly—December 2020 . 51 Appeals Proceedings of SACSCOC College Delegate Assembly . 53 4 2020 Roll of Accredited and Candidate Institutions . 54 Institutions Awarded Initial Membership in 2020 . 55 Member Institutions with a Change of Status in 2020 . 55 Profile of Member and Candidate Institutions: by State, by Degree Level, and by Governance as of December 31, 2020 . 56 2020 Roll of Accredited and Candidate Institutions . 57 5 Financial Statements and Independent Auditor’s Report: June 30, 2020 . 82 SACSCOC 2020 Annual Report and Proceedings 3 As we experienced 2020 as a year of disruption, I am proud of the membership, volunteers, “ and SACSCOC staff who exhibited extraordinary flexibility as we adapted to meet the major challenges facing all of us. -

SAILS Acceptance List

SAILS Acceptance List The following institutions currently accept SAILS completion in place of learning support/ remediation math requirements. TBR- The College System of TN Community Colleges Chattanooga State Community College Northeast State Community College Cleveland State Community College Pellissippi State Community College Columbia State Community College Roane State Community College Dyersburg State Community College Southwest Tennessee Community College Jackson State Community College Volunteer State Community College Motlow State Community College Walters State Community College Nashville State Community College The Tennessee Colleges of Applied Technology (TCAT) Please note: SAILS is not applicable to students entering Allied Health programs. TCAT Athens TCAT McKenzie TCAT Chattanooga TCAT McMinnville TCAT Covington TCAT Memphis TCAT Crossville TCAT Morristown TCAT Crump TCAT Murfreesboro TCAT Dickson TCAT Nashville TCAT Elizabethton TCAT Newbern TCAT Harriman TCAT Oneida TCAT Hartsville TCAT Paris TCAT Hohenwald TCAT Pulaski TCAT Jacksboro TCAT Ripley TCAT Jackson TCAT Shelbyville TCAT Knoxville TCAT Whiteville TCAT Livingston The following institutions have accepted SAILS completion in place of learning support/ remediation math requirements. SAILS cannot guarantee that acceptance will continue at any institution. The SAILS Central Office will assist enrolled postsecondary students in petitioning the recognition of the SAILS completion credential at private and out-of-state institutions. Contact the SAILS Central Office -

ANNUAL REPORT 2 | CCCU 2019-20 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents CCCU LEADERSHIP 2019-20 2 Shirley V

COUNCIL FOR CHRISTIAN COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES 2019-20 ANNUAL REPORT 2 | CCCU 2019-20 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents CCCU LEADERSHIP 2019-20 2 Shirley V. Hoogstra, J.D. Kimberly Battle-Walters Denu, Ph.D. ABOUT THE President Vice President for CCCU Educational Programs Mandi Bolton Vice President for Finance and Stan Rosenberg, Ph.D. 5 Administration Vice President for Research GOVERNMENT and Scholarship RELATIONS CCCU BOARD OF DIRECTORS 9 Lowell Haines, J.D., Ed.D. Shirley A. Mullen, Ph.D. NETWORKING & President, Houghton College Higher Education Attorney/Consul- COLLABORATION Chair tant David Wright, Ph.D. Erik Hoekstra, Ph.D. 14 President, Indiana Wesleyan University President, Dordt University RACIAL & Vice Chair ETHNIC DIVERSITY Sidney J. Jansma Jr., M.B.A. Derek Halvorson, Ph.D. Chair of the Board, Wolverine Gas President, Covenant College and Oil Corporation 16 Secretary L. Randolph Lowry III, M.P.A., J.D. EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION Robin E. Baker, Ph.D. President, Lipscomb University President, George Fox University Treasurer Charles W. Pollard, J.D., Ph.D. President, John Brown University 20 Bishop Claude Alexander, Jr., M.Div., DEVELOPMENT D.Min. Claude O. Pressnell Jr., Ed.D. Senior Pastor, The Park Church President, Tennessee Independent Colleges & Universities Association 22 Dan Boone, D.Min FINANCIAL President, Trevecca Nazarene University Philip Graham Ryken, M.Div., INFORMATION D.Phil. Peggy S. Campbell President, Wheaton College President, Ambassador Advertising Agency Evans P. Whitaker, Ph.D. 24 President, Anderson University OUR Andy Crouch, M.Div. INSTITUTIONS Partner for Theology and Culture, Shirley V. Hoogstra, J.D. Praxis President, CCCU Ex-Officio CCCU 2019-20 ANNUAL REPORT | 1 A Letter from President Shirley V. -

2021 ACA Ledford Scholars Awardees

2021 ACA Ledford Scholars Awardees The Appalachian College Association is very pleased to announce the award recipients of this year's Ledford Scholars Program. These undergraduate students are provided financial support enabling them to work on a significant research project during the summer of 2021. Each student will receive assistance from a faculty mentor at her/his home institution. During the fall semester, the Scholars provide a video presentation of their research findings, which is recognized and made available for viewing on the ACA's website. Student Name Institution Academic Major(s) Proposal Topic Faculty Mentor The Effects of Non-Nutritive Sweeteners on Lipid Metabolism in Sydney Bailey King University Cell & Molecular Biology the Model Organism C. elegens Laura Kelly Vaughan The Impact of the Printing Press on the Spread of the Charity Beam Johnson University History Protestant Reformation Gerald Mattingly Tracing microbial community structure in marine sediments of Arianna Brown Maryville College Biochemistry/ Exercise Science Svalbard, high Arctic (79°N) with quantitative PCR Joy Buongiorno Connor Buchanan Emory & Henry College Exercise Science Exploring the Impact of Covid-19 on Appalachian Adolescents J.P. Barfield Criminal Justice A qualitative Analysis: Interviews with family members of Alexa Calix Campbellsville University Administration capital murder victims Dale Wilson Assorted Arboreal Appalachian Arachnids: A Study of Biodiversity and Habitat in Appalachian Arboreal Jumping Thomas Cocks Lee University Biological -

Higher Education Allocation

HEERF II Allocations for Public and Nonprofit Institutions under CRRSAA section 314(a)(1) 1/13/2021 CARES Act Minimum Amount Section 314(a)(1)(E) Minimum Amount Maximum Amount for Emergency & Section for Student Aid for Institutional Financial Aid Grants 314(a)(1)(F) Portion (CFDA Portion (CFDA OPEID Institution Name School Type State Total Award to Students Allocation 84.425E Allocation) 84.425F Allocation) 00100200 Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University Public AL $ 14,519,790 $ 4,560,601 $ 37,515 $ 4,560,601 $ 9,959,189 00100300 Faulkner University Private Non‐Profit AL $ 4,333,744 $ 1,211,489 $ 239,004 $ 1,211,489 $ 3,122,255 00100400 University of Montevallo Public AL $ 4,041,651 $ 1,280,001 $ ‐ $ 1,280,001 $ 2,761,650 00100500 Alabama State University Public AL $ 10,072,950 $ 3,142,232 $ 174,255 $ 3,142,232 $ 6,930,718 00100700 Central Alabama Community College Public AL $ 2,380,348 $ 611,026 $ 32,512 $ 611,026 $ 1,769,322 00100800 Athens State University Public AL $ 2,140,301 $ 422,517 $ 492,066 $ 492,066 $ 1,648,235 00100900 Auburn University Public AL $ 23,036,339 $ 7,822,873 $ 31,264 $ 7,822,873 $ 15,213,466 00101200 Birmingham‐Southern College Private Non‐Profit AL $ 1,533,280 $ 534,928 $ ‐ $ 534,928 $ 998,352 00101300 Calhoun Community College Public AL $ 10,001,547 $ 2,196,124 $ 332,365 $ 2,196,124 $ 7,805,423 00101500 Enterprise State Community College Public AL $ 2,555,815 $ 620,369 $ 45,449 $ 620,369 $ 1,935,446 00101600 University of North Alabama Public AL $ 8,666,299 $ 2,501,324 $ 137,379 $ 2,501,324 $ 6,164,975 00101700 Gadsden State Community College Public AL $ 7,581,323 $ 1,878,083 $ 219,704 $ 1,878,083 $ 5,703,240 00101800 George C. -

Emmanuel Envoy Magazine Fall 2020

ENVOY FALL 2020 ALUMNI SPOTLIGHT: PHIL TATUM Phil Tatum graduated from Emmanuel in 2018 with a Despite the challenges of working full time, being a Master of Arts in Christian Ministries (MACM). husband, raising two children, and adopting a third in While an undergrad at Georgia Tech studying industrial the middle of his degree program, the MACM experience engineering, Tatum participated in the Georgia Tech served him well. Christian Campus Fellowship. His involvement there led “I think the MACM taught me how to read and study to an internship with the campus ministry and a growing scripture in new ways. I grew in the area of pastoral care interest in pursuing ministry work. Following graduation, through Dr. Holland’s classes. I honestly think I grew as Tatum moved to Santiago, Chile, to plant a campus a minister, a leader, a thinker, a Christ-follower, and a ministry with CMF/Globalscope. human through the program. I believe there is more depth After more than four years in Chile, Tatum and his in my ministry now than there was before I entered the family returned to the States, and he began working program,” said Tatum. at CMFI’s headquarters The MACM is a three-year, 48-credit hour practical in Indianapolis, Indiana. ministries program designed to enhance the work For the past 10 years, he students are already doing in ministry, without relocation. has served as director of This distance-education degree’s curriculum combines Globalscope, overseeing the both online courses and one or two on-campus residency program’s 14 international weeks each year.