The Spirituality of Psalm 1311

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humility and Hope Psalm 131

Rock Valley Bible Church (www.rvbc.cc) # 2013-027 July 14, 2013 by Steve Brandon Humility and Hope Psalm 131 1. Humility (verses 1-2) 2. Hope (verse 3) The Bible says that King David was a man after God's own heart (1 Samuel 15:14; Acts 13:22). David loved the LORD (Psalm 18:1). David took refuge in the LORD(Psalm 18:2). David called upon the LORD (Psalm 18:3). David prayed to the LORD (Psalm 5:3). David gave thanks to the LORD with all of his heart (Psalm 9:1). David told others of the wonders of the LORD (Psalm 9:1). David was glad in the LORD(Psalm 9:2). David sang praise to the LORD (Psalm 9:2). David blessed the LORD (Psalm 16:7). David found his greatest joy in the LORD (Psalm 4:7). And because David was a man after God's own heart, he "found favor in God's sight" (Acts 7:46). God heard David's prayers (Psalm 18:6). God saved David from his enemies (Psalm 18:3). Now, surely, you know enough about human nature to know that David was not perfect. He was a man of war (1 Chronicles 29:3). He was a man of bloodshed (1 Chronicles 29:3). He committed adultery (2 Samuel 11). He committed murder (2 Samuel 11). He tried to cover up his sin (2 Samuel 12). And yet, David did repent. David confessed his sin to the LORD (Psalm 32:5). David pleaded for God's grace (Psalm 51:1). -

One of the Shortest Psalms to Read and the Longest to Learn” Psalm 131 21 May 2017

“One Of The Shortest Psalms To Read And The Longest To Learn” Psalm 131 21 May 2017 Charles Spurgeon said that Psalm 131 was one of the shortest psalms to read but the longest psalm to learn. How true! You can read this psalm in about 10 seconds, but it will take you your whole life to learn it. And by the time you get through this sermon, I think you’ll agree. Psalm 131 is not the shortest of the psalms, Psalm 117 is, but it’s pretty short and it does take a looooong time to learn- like the rest of your life. Psalm 131 shows us that we all struggle with fear and worry and anxiety and panic at times. We all do to some degree. And some of us really struggle with anxiety and panic attacks. So I know that there is not easy answer to all of these issues. Some people struggle with severe cases of anxiety and panic attacks that are debilitating. I had a pastor friend call me this week and tell me that he suffered a massive panic attack that sent him to the hospital. And in that moment, it would not have mattered if you quoted Psalm 131 to him because he was out of it. Of course, we want to share Scripture with people- it’s God’s word for crying out loud! But sometimes it isn’t as simple as just quoting a Scripture to someone. It may require medicine. Now, I don’t want to get into a debate on the validity of using medicine to help, but I will say this, that my friend said that it is helping him. -

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: the Master Musician's Melodies

Psalms, Hymns, and Spiritual Songs: The Master Musician’s Melodies Bereans Adult Bible Fellowship Placerita Baptist Church 2009 by William D. Barrick, Th.D. Professor of OT, The Master’s Seminary Psalm 131 — Godly Contentment 1.0 Introducing Psalm 131 y In the Psalms of Ascents’ five sets of three psalms, we find a theme of distress in the first, power in the second, and security in the third, Psalm 131 speaks of security (cp. Pss 122, 125, and 128), illustrating it with a weaned child’s secure relationship to his mother. y Their style and their theme of hope link Psalms 130 and 131 (see notes on Ps 130). We can fulfill Psalm 131’s lesson for ourselves by living out Psalm 130. y Theme of Psalm 131: Troubled travelers humbly and contentedly hope in God. y As we approach this psalm, it behooves us to “understand rightly what Psalm 131 describes. This composure is learned, and it is learned in relationship. Such purposeful quiet is achieved, not spontaneous. It is conscious, alert, and chosen. It is a form of self-mastery by the grace of God: ‘Surely I have composed and quieted my soul.’ And it happens in living relationship with Someone Else. Can you get to this quieted place, here and now, in your actual life? Yes. This psalm is from a man who leads you by the hand. The last sentence of the psalm stops talking with God and talks to you. Psalm 131 aims to become your words as a chosen and blessed child.” — David Powlison, Seeing with New Eyes: Counseling and the Human Condition through the Lens of Scripture, Resources for Changing Lives (Phillipsburg, NJ: P & R Publishing, 2003), 77, emphasis his. -

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133

Daily Devotions in the Psalms Psalm 129-133 Monday 12th October - Psalm 129 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth”— let Israel now say— 2 “Greatly have they afflicted me from my youth, yet they have not prevailed against me. 3 The plowers ploughed upon my back; they made long their furrows.” 4 The Lord is righteous; he has cut the cords of the wicked. 5 May all who hate Zion be put to shame and turned backward! 6 Let them be like the grass on the housetops, which withers before it grows up, 7 with which the reaper does not fill his hand nor the binder of sheaves his arms, 8 nor do those who pass by say, “The blessing of the Lord be upon you! We bless you in the name of the Lord!” It is interesting that Psalm 128 and 129 sit side by side. They seem to sit at odds with one another. Psalm 128 speaks of Yahweh blessing his faithful people. They enjoy prosperity and the fruit of their labour. It is a picture of peace and blessing. And then comes this Psalm, clunking like a car accidentally put into reverse. Here we see a people long afflicted (v. 1-2). As a nation, they have had their backs ploughed. And the rest of the Psalm prays for the destruction of the wicked nations and individuals who would seek to harm and destroy Israel. It’s possible that this Psalm makes you feel uncomfortable, or even wonder if this Psalm is appropriate for the lips of God’s people. -

Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016)

James Block Complete Song Book (2013 - 2016) Contents ARISE OH YAH (Psalm 68) .............................................................................................................................................. 3 AWAKE JERUSALEM (Isaiah 52) ................................................................................................................................... 4 BLESS YAHWEH OH MY SOUL (Psalm 103) ................................................................................................................ 5 CITY OF ELOHIM (Psalm 48) (Capo 1) .......................................................................................................................... 6 DANIEL 9 PRAYER .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 DELIGHT ............................................................................................................................................................................ 8 FATHER’S HEART ........................................................................................................................................................... 9 FIRSTBORN ..................................................................................................................................................................... 10 GREAT IS YOUR FAITHFULNESS (Psalm 92) ............................................................................................................. 11 HALLELUYAH -

Psalm 130 Pastor Jason Van Bemmel a Song of Ascents. 1 out of the Depths I Cry to You, O LORD!

Out of the Depths, Redemption! Psalm 130 Pastor Jason Van Bemmel A Song of Ascents. 1 Out of the depths I cry to you, O LORD! 2 O Lord, hear my voice! Let your ears be attentive to the voice of my pleas for mercy! 3 If you, O LORD, should mark iniquities, O Lord, who could stand? 4 But with you there is forgiveness, that you may be feared. 5 I wait for the LORD, my soul waits, and in his word I hope; 6 my soul waits for the Lord more than watchmen for the morning, more than watchmen for the morning. 7 O Israel, hope in the LORD! For with the LORD there is steadfast love, and with him is plentiful redemption. 8 And he will redeem Israel from all his iniquities. Introduction: Singing the Blues to God I love music, and I tend to like music that has a bit of a dark edge to it – good music, that is, like the blues. I enjoyed listening to Muddy Waters on the flight back from Dubai in July. My favorite Christian singer-songwriter is Andrew Peterson, who also tends to have a raw, honest edge to his music, which is both dark and hopeful, a blend of melancholy and joy. Perhaps the same thing which makes my taste is music tend toward the blues also makes me love Psalm 130. I don’t know if I can say for sure that Psalm 130 is my absolute favorite psalm. That’s almost like asking me which of my children is my favorite. -

Peace, Be Still: Learning Psalm 131 by Heart

From the Editor’s Desk “Peace, be still”: Learning Psalm 131 by Heart by David Powlison od speaks to us in many different n’t churn inside. Failure and despair don’t ways. When you hear, “Now it came haunt him. Anxiety isn’t spinning him into Gto pass,” settle down for a good free fall. He isn’t preoccupied with thinking story. When God asserts, “I am,” trust His up the next thing he wants to say. Regrets self-revelation. When He promises, “I will,” don’t corrode his inner experience. Irritation bank on it. When He tells you, “You shall… and dissatisfaction don’t devour him. He’s you shall not,” do what He says. Psalm 131 not stumbling through the mine field of is in yet a different vein. Most of it is holy blind longings and fears. eavesdropping. You have intimate access to He’s quiet. the inner life of someone who has learned Are you quiet inside? Is Psalm 131 your composure, and then he invites you to come experience, too? When your answer is No, it along. Psalm 131 is show-and-tell for how to naturally invites follow-up questions. What become peaceful inside. Listen in. is the “noise” going on inside you? Where LORD, does it come from? How do you get busy my heart is not proud, and preoccupied? Why? Do you lose your and my eyes are not haughty, composure? When do you get worried, irri- and I do not go after things too great table, wearied, or hopeless? How can you and too difficult for me. -

The Composition of the Book of Psalms

92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina V BIBLIOTHECA EPHEMERIDUM THEOLOGICARUM LOVANIENSIUM CCXXXVIII THE COMPOSITION OF THE BOOK OF PSALMS EDITED BY ERICH ZENGER UITGEVERIJ PEETERS LEUVEN – PARIS – WALPOLE, MA 2010 92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina IX INHALTSVERZEICHNIS VORWORT . VII EINFÜHRUNG . 1 HAUPTVORTRÄGE Erich ZENGER (Münster) Psalmenexegese und Psalterexegese: Eine Forschungsskizze . 17 Jean-Marie AUWERS (Louvain-la-Neuve) Le Psautier comme livre biblique: Édition, rédaction, fonction 67 Susan E. GILLINGHAM (Oxford) The Levitical Singers and the Editing of the Hebrew Psalter . 91 Klaus SEYBOLD (Basel) Dimensionen und Intentionen der Davidisierung der Psalmen: Die Rolle Davids nach den Psalmenüberschriften und nach dem Septuagintapsalm 151 . 125 Hans Ulrich STEYMANS (Fribourg) Le psautier messianique – une approche sémantique . 141 Frank-Lothar HOSSFELD (Bonn) Der elohistische Psalter Ps 42–83: Entstehung und Programm 199 Yair ZAKOVITCH (Jerusalem) The Interpretative Significance of the Sequence of Psalms 111–112.113–118.119 . 215 Friedhelm HARTENSTEIN (Hamburg) „Schaffe mir Recht, JHWH!“ (Psalm 7,9): Zum theologischen und anthropologischen Profil der Teilkomposition Psalm 3–14 229 William P. BROWN (Decatur, GA) “Here Comes the Sun!”: The Metaphorical Theology of Psalms 15–24 . 259 Bernd JANOWSKI (Tübingen) Ein Tempel aus Worten: Zur theologischen Architektur des Psalters . 279 92988_Zenger_vrwrk 28-06-2010 11:55 Pagina X X INHALTSVERZEICHNIS SEMINARE Harm VAN GROL (Utrecht) David and His Chasidim: Place and Function of Psalms 138–145 . 309 Jacques TRUBLET (Paris) Approche canonique des Psaumes du Hallel . 339 Brian DOYLE (Leuven) Where Is God When You Need Him Most? The Divine Metaphor of Absence and Presence as a Binding Element in the Composition of the Book of Psalms . -

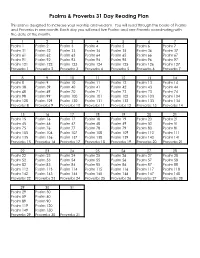

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan

Psalms & Proverbs 31 Day Reading Plan This plan is designed to increase your worship and wisdom. You will read through the books of Psalms and Proverbs in one month. Each day you will read five Psalms and one Proverb coordinating with the date of the month. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Psalm 1 Psalm 2 Psalm 3 Psalm 4 Psalm 5 Psalm 6 Psalm 7 Psalm 31 Psalm 32 Psalm 33 Psalm 34 Psalm 35 Psalm 36 Psalm 37 Psalm 61 Psalm 62 Psalm 63 Psalm 64 Psalm 65 Psalm 66 Psalm 67 Psalm 91 Psalm 92 Psalm 93 Psalm 94 Psalm 95 Psalm 96 Psalm 97 Psalm 121 Psalm 122 Psalm 123 Psalm 124 Psalm 125 Psalm 126 Psalm 127 Proverbs 1 Proverbs 2 Proverbs 3 Proverbs 4 Proverbs 5 Proverbs 6 Proverbs 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Psalm 8 Psalm 9 Psalm 10 Psalm 11 Psalm 12 Psalm 13 Psalm 14 Psalm 38 Psalm 39 Psalm 40 Psalm 41 Psalm 42 Psalm 43 Psalm 44 Psalm 68 Psalm 69 Psalm 70 Psalm 71 Psalm 72 Psalm 73 Psalm 74 Psalm 98 Psalm 99 Psalm 100 Psalm 101 Psalm 102 Psalm 103 Psalm 104 Psalm 128 Psalm 129 Psalm 130 Psalm 131 Psalm 132 Psalm 133 Psalm 134 Proverbs 8 Proverbs 9 Proverbs 10 Proverbs 11 Proverbs 12 Proverbs 13 Proverbs 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Psalm 15 Psalm 16 Psalm 17 Psalm 18 Psalm 19 Psalm 20 Psalm 21 Psalm 45 Psalm 46 Psalm 47 Psalm 48 Psalm 49 Psalm 50 Psalm 51 Psalm 75 Psalm 76 Psalm 77 Psalm 78 Psalm 79 Psalm 80 Psalm 81 Psalm 105 Psalm 106 Psalm 107 Psalm 108 Psalm 109 Psalm 110 Psalm 111 Psalm 135 Psalm 136 Psalm 137 Psalm 138 Psalm 139 Psalm 140 Psalm 141 Proverbs 15 Proverbs 16 Proverbs 17 Proverbs 18 Proverbs 19 Proverbs 20 Proverbs 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Psalm 22 Psalm 23 Psalm 24 Psalm 25 Psalm 26 Psalm 27 Psalm 28 Psalm 52 Psalm 53 Psalm 54 Psalm 55 Psalm 56 Psalm 57 Psalm 58 Psalm 82 Psalm 83 Psalm 84 Psalm 85 Psalm 86 Psalm 87 Psalm 88 Psalm 112 Psalm 113 Psalm 114 Psalm 115 Psalm 116 Psalm 117 Psalm 118 Psalm 142 Psalm 143 Psalm 144 Psalm 145 Psalm 146 Psalm 147 Psalm 148 Proverbs 22 Proverbs 23 Proverbs 24 Proverbs 25 Proverbs 26 Proverbs 27 Proverbs 28 29 30 31 Psalm 29 Psalm 30 Psalm 59 Psalm 60 Psalm 89 Psalm 90 Psalm 119 Psalm 120 Psalm 149 Psalm 150 Proverbs 29 Proverbs 30 Proverbs 31. -

Developing a Life of Devotion / Part 1 Psalm 131 Sunday / 6 August 2006 2Nd Street Community Church Gregg Lamm, Lead Pastor-Teacher

DEVELOPING A LIFE OF DEVOTION / PART 1 PSALM 131 SUNDAY / 6 AUGUST 2006 2ND STREET COMMUNITY CHURCH GREGG LAMM, LEAD PASTOR-TEACHER .PPT 1 … This morning is the first of four Sunday morning teachings on the topic of Developing A Life Of Devotion … And we’re going to look at PSALM 131 as God’s blueprint for our perspective, for our focus, for how God wants our hearts to be shaped and molded so that we can begin to become the people He wants for us to become. Let’s take a moment and be reminded and be reconnected with our Mission Statement here at 2nd Street … .PPT 2 … COOPERATING WITH GOD TO DEVELOP SPIRITUAL SEEKERS INTO COMMITTED DISCIPLES OF JESUS CHRIST. And then over the next three Sunday mornings we’ll look at how to pursue and maintain a life-of-devotion with God. What does it mean to “study” the Bible? What does it mean to pursue a prayer life? What does it mean to be intentional and consistent in our “with-God-life”? The author and poet T.S. Elliott asked the question, “Can a lifetime portray a single motive?” Philosopher Frederick Nietzsche put it another way when he wrote that what followers-of-Christ need to do in order to make a difference in this word, is to have “a long obedience in the same direction.” So “can a lifetime portray a single motive? Can you and I have a long obedience in the same direction?” If it's about us, "no" we can’t live life portraying a single motive. -

Psalms Part 5

OVERVIEW FOR PSALMS Jesus grew up with a Psalter - book of songs (hymnbook) that were sung as prayers. The Psalms were written in response to the composer’s experience of God’s presence or perceived absence during a specific episode in life. Each Psalm is written with a general form so that others could use the Psalm to address similar experiences through song and prayer. The Psalms provided a means and a template which formed and trained God’s people how to approach God with every kind of experience known to man. God wants us to come to him with our whole being. There are several different genres that provide ways for us to express our hearts to God and provide a means to commune with God. Through praying and singing these Psalms, God will meet us and transform us in the process. PART 5: PILGRIMAGE SONGS Read the text: Psalms 127 & 131 Psalm 127 A Song of Ascents. Of Solomon. Unless the Lord builds the house, those who build it labor in vain. Unless the Lord watches over the city, the watchman stays awake in vain. It is in vain that you rise up early and go late to rest, eating the bread of anxious toil; for he gives to his beloved sleep. Behold, children are a heritage from the Lord, the fruit of the womb a reward. Like arrows in the hand of a warrior are the children of one's youth. Blessed is the man who fills his quiver with them! He shall not be put to shame when he speaks with his enemies in the gate. -

Psalm 131-133

Book of Psalms Psalms 131-133 Psalms 120-134 are called “songs of degrees” or “songs of ascent.” God’s people sang them as they traveled to Jerusalem for the three sacred feasts (Passover, Pentecost, and Tabernacles). They are called “songs of ascent or degrees” because Jerusalem is about 2,700 feet in elevation. Jewish worshipers sang these jubilant songs as they made their pilgrimage upward to Jerusalem. Four of the songs were written by David (Ps. 122, 124, 131, and 133). Psalm 131 – A Childlike Faith in God The Bible calls us to be childlike in our faith (Matt. 18:3). As a believer matures spiritually, he becomes more childlike in his faith. In the same way a child depends on his parents to meet his needs, we should look to God in simple dependence. 1. A childlike humility before God (vs. 1) David rejects pride, haughtiness, and selfish ambition. God resists the proud, but gives grace to the humble (Jas. 4:6). 2. A childlike hush before God (vs. 2) David describes himself as a child who is old enough to be weaned, yet not old enough to care for himself. He has learned to be quietly submissive while relying on God. 3. A childlike hope in God (vs. 3) David urges God’s people to hope in Him. Hope is the assurance that God is working all things for the ultimate good of His people (Rom. 8:28). Steven Lawson comments: “This psalm should be the confession of all believers. Every saint should have a childlike faith in God.