The Right Vessel for Offshore Cruising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Letter January 2012

NEWS LETTER JANUARY 2012 DICKERSON HISTORY A Historical Review Committee consisting of Barry Creighton, Paula and Jim Karr, D and Don Wogaman and the writer has compiled a Historical Review of Dickerson Boatbuilders from it’s humble beginning at Bill Dickerson’s back yard at Church Creek, Maryland in 1946 to Trappe and the building of the last Dickerson in 1987. The Dickerson Owners web site http://dickersonowners.org/ features a short video of this fabulous history and a 16 page document with photos. At the 2012 Dickerson Rendezvous, June 15-17, we will celebrate the Dickerson Boatbuilders by inviting those that are still with us and the relatives of those that have moved on to visit with us and join in this celebration. In compiling this history, it was heartwarming to talk to the relatives of those that have passed on like Preston Brannock and Donald Griffin and those that are still with us like Tom Lucke, Ted Reed and our own Jim and Paula Karr (who played such active roles in the organization and got married while working for the Dickerson firm). Following is a note that we received from Ted Reed who bought Dickerson Boatbuilders in December of 1978 with his friend Bennett Dorrance and built the D-37, D-50, and Farr 37 in addition to the D-41 and D-36; started a charter service, and built a new marina. Joe Slavin, “Irish Mist” “Dear Joe, First I want to thank you and the others involved in compiling the Dickerson History and keeping the Dickerson Association alive and well. -

Watch Hill When the Force IS with You the Sea That Never Sleep

Sailing the Northeast When the Force IS with You The Sea that Never Sleeps Destination: Watch Hill June 2018 • FREE www.windcheckmagazine.com Molded Composites IF YOU DON’T WANT TO GIVE UP SPEED FOR DURABILITY THEN DON’T. GO BEYOND EXPECTATIONS MILFORD, CT 203-877-7621 HUNTINGTON, NY 631-421-7245 northsails.com v MCMICHAEL YACHT BROKERS Experience counts. Mamaroneck, NY 10543 Newport, RI 02840 914-381-5900 401- 619 - 5813 The new J/121 is racing on LIS this summer and multiple boats headed for Bermuda. Call for your sea trial! The new MJM 43z outboard express The new Hanse 418 available for cruiser. Sea trials now available. mid-summer delivery. The new Amel 50 luxury passagemaker. Dehler 38 on display and available Contact us for sea trials. for late summer delivery. See our listings in the Brokerage Section www.mcmyacht.com Windcheck P4CB - June 2018.indd 1 5/14/2018 3:53:41 PM publisher's log Sailing the Northeast Issue 175 Don’t let Perfect be the enemy of Good (enough) Publisher Benjamin Cesare My father was an artisan. He loved craft and beauty. So much so that as a kid, [email protected] if I wanted to fashion a new Laser tiller in his shop, I had to be sure to cut and Associate Publisher drill the Montreal hockey stick and attach the PVC tube for a tiller extension Anne Hannan when he was not around. Otherwise, while he might appreciate my logic for [email protected] the weight-to-strength ratio of those laminated Montreal shafts, he would be Editor-at-Large far more concerned with why I had not chosen mahogany. -

Live Auction Items

2013 Spring Gala Auction Catalog Live Auction Items Item Title Value Category Donor Description Restrictions # 4 One-Day Park Hopper passes for admission at each theme park. 4 One Day Disney Park Passes expire within two years cannot be upgraded or applied toward a A331 Hopper Passes $480 Live Walt Disney World package to meet eligibility requirements. Cannot be upgraded Chesapeake Bay Day Sailing with the Toths. Take sail on a Dickerson 37' sailboat, lunch at Date to be mutually agreed upon A339 Sail $600 Live Bill & Gail Toth anchor, dinner at Masthead Restaurant at Pier Street, Oxford, MD by winner and owners. Valid May 2013 - April 2014. Excludes all major holiday periods. Otherwise subject to availability. Max occupancy 6 persons. Does not include daily housekeeping. No Smoking, No Pets. Please contact see www.micasadelsol.com for Enjoy 5 nights in a privately owned 2300 sq. ft. ocean front penthouse availability and email Jennifer at Five Nights in a Luxury condo just 6 miles from Cabo San Lucas. For more information please [email protected] for A392 Ocean Front Cabo Condo $4,000 Live Mi Casa del Sol visit http://www.micasadelsol.com booking. MSO parent Mariam Anwarzai will bring dinner for 10 to your house on a mutually agreed upon date. She will work with you to match your preferences and dietetic needs. Enjoy the flavor of Afghani foods. Menu selections include: Appetizers of Bouranee Baujaun: sauteed eggplant and peppers with homemade yougurt and Afghan bread, Maust-O-Khari: homemade yogurt with diced cucumbers and Boolawnee: pastry stuffed with chopped leek, potato and herb. -

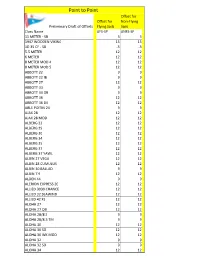

Copy of P2P Ratings for Release Dr Mod.Xlsx

Point to Point Offset for Offset for Non-Flying Preliminary Draft of Offsets Flying Sails Sails Class Name ΔFS-SP ΔNFS-SP 11 METER - SB 3 3 1947 WOODEN VIKING 15 15 1D 35 CF - SB -3 -3 5.5 METER 12 12 6 METER 12 12 8 METER MOD 4 12 12 8 METER MOD 5 12 12 ABBOTT 22 9 9 ABBOTT 22 IB 9 9 ABBOTT 27 12 12 ABBOTT 33 9 9 ABBOTT 33 OB 9 9 ABBOTT 36 12 12 ABBOTT 36 DK 12 12 ABLE POITIN 24 9 9 AJAX 28 12 12 AJAX 28 MOD 12 12 ALBERG 22 12 12 ALBERG 29 12 12 ALBERG 30 12 12 ALBERG 34 12 12 ALBERG 35 12 12 ALBERG 37 12 12 ALBERG 37 YAWL 12 12 ALBIN 27 VEGA 12 12 ALBIN 28 CUMULUS 12 12 ALBIN 30 BALLAD 9 9 ALBIN 7.9 12 12 ALDEN 44 9 9 ALERION EXPRESS 20 12 12 ALLIED 3030 CHANCE 12 12 ALLIED 32 SEAWIND 12 12 ALLIED 42 XL 12 12 ALOHA 27 12 12 ALOHA 27 OB 12 12 ALOHA 28/8.5 9 9 ALOHA 28/8.5 TM 9 9 ALOHA 30 12 12 ALOHA 30 SD 12 12 ALOHA 30 WK MOD 12 12 ALOHA 32 9 9 ALOHA 32 SD 9 9 ALOHA 34 12 12 Point to Point Offset for Offset for Non-Flying Preliminary Draft of Offsets Flying Sails Sails Class Name ΔFS-SP ΔNFS-SP ALOHA 8.2 12 12 ALOHA 8.2 OB 12 12 AMF 2100 12 12 ANCOM 23 12 12 ANDREWS 30 CUS 1 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 2 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 3 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 4 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 5 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 6 L30 9 9 ANDREWS 30 CUS 7 L30 9 9 ANTRIM 27 IB - SB -9 -9 ANTRIM 27 OB - SB -9 -9 APHRODITE 101 9 9 AQUARIUS 23 9 9 ARCHAMBAULT 31 6 6 ARCHAMBAULT 35 CF 3 3 ARCHAMBAULT 40RC CF MOD 3 3 ATLANTIC 12 12 AURORA 40 KCB 9 9 AVANCE 36 12 12 B 25 -SB 3 3 B 32 OB MOD -SB -3 -3 BALATON 31 12 12 BALBOA 26 SK 9 9 BALTIC 42 C&C 9 9 BALTIC 42 DP 9 9 BANNER -

News Letter October 2012

NEWS LETTER OCTOBER 2012 Dickerson Sailors Battle Strong Winds Wow, what a Western Shore Round-Up! The fleet for the Dickerson Sixth Western Shore Round-Up at West River battled 15-20 knot winds with gusts up to 25 knots during the September 8 th Race. Our Commodore Pat Ewing lost the mast of his wooden 40 foot Dickerson Ketch “VelAmore ” when a bronze turnbuckle broke. Pat with his young crew did an amazing job cleaning up the mess and getting back to port under power. We are all thankful that no one was hurt. Our appreciation goes to Dickerson Captains Barry Creighton “Crew Rest ” and Rick Woytowich “Belle ” who were racing near “ VelAmore ” when it’s mast and rigging went down and immediately withdrew from the race to help Pat get safely to shore. After the race, the Dickerson fleet, at the dock or on a mooring, survived a severe squall with torrential rain. 1 Left to right: Jim and John Freal, Sheriff Parker Hallam, Randy Bruns and Peter Oetker Our thanks to Randy and Barb Bruns for organizing this terrific event. The Friday night cook out at the West River Sailing Club and the Awards Dinner at Pirates Cove Restaurant went off perfectly with plenty of good cheer and all were certainly thankful to be safe. Congratulations go to the new Sheriff of the Western Shore Parker Hallam, 36 sloop “Frigate Connie ,” who won overall and also won the 35/36 class. New member Peter Oetker’s 39 sloop “Vignette ” won the 39-41 class and Bill Toth’s “ Starry Night ” won the 37 class. -

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE and MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the Years 2005 Through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE AND MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the years 2005 through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages lists base performance handicaps (BHCPs) and low, high, average, and median performance handicaps reported by US PHRF Fleets for well over 4100 boat classes or types displayed in Adobe Acrobat portable document file format. Use Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, to display specific information in this list for each class. Class names conform to US PHRF designations. The information for this list was culled from data sources used to prepare the “History of US PHRF Affiliated Fleet Handicaps for 2011”. This reference book, published annually by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION, is often referred to as the “Red, White, & Blue book of PHRF Handicaps”. The publication lists base handicaps in seconds per mile by Class, number of actively handicapped boats by Fleet, date of last reported entry and other useful information collected over the years from more than 60 reporting PHRF Fleets throughout North America. The reference is divided into three sections, Introduction, Monohull Base Handicaps, and Multihull Base Handicaps. Assumptions underlying determination of PHRF Base Handicaps are explicitly listed in the Introduction section. The reference is available on-line to US SAILING member PHRF fleets and the US SAILING general membership. A current membership ID and password are required to login and obtain access at: http://offshore.ussailing.org/PHRF/2011_PHRF_Handicaps_Book.htm . Precautions: Reported handicaps base handicaps are for production boats only. One-off custom designs are not included. A base handicap does not include fleet adjustments for variances in the sail plan and other modifications to designed hull form and rig that determine the actual handicap used to score a race. -

High-Low-Mean PHRF Handicaps

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages list low, high and average performance handicaps reported by USPHRF Fleets for over 4100 boat classes/types. Using Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, information can be displayed for each boat class upon request. Class names conform to USPHRF designations. The source information for this listing also provides data for the annual PHRF HANDICAP listings (The Red, White, & Blue Book) published by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION. This publication also lists handicaps by Class/Type, Fleet, Confidence Codes, and other useful information. Precautions: Handicap data represents base handicaps. Some reported handicaps represent determinations based upon statute rather than nautical miles. Some of the reported handicaps are based upon only one handicapped boat. The listing covers reports from affiliated fleets to USPHRF for the period March 1995 to June 2008. This listing is updated several times each year. HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS ORGANIZED BY CLASS/TYPE Lowest Highest Average Class\Type Handicap Handicap Handicap 10 METER 60 60 60 11 METER 69 108 87 11 METER ODR 72 78 72 1D 35 27 45 33 1D48 -42 -24 -30 22 SQ METER 141 141 141 30 SQ METER 135 147 138 5.5 METER 156 180 165 6 METER 120 158 144 6 METER MODERN 108 108 108 6.5 M SERIES 108 108 108 6.5M 76 81 78 75 METER 39 39 39 8 METER 114 114 114 8 METER (PRE WW2) 111 111 111 8 METER MODERN 72 72 72 ABBOTT 22 228 252 231 ABBOTT 22 IB 234 252 -

Valid List by Design

Date: 12/25/2010 2010 Valid List by Design, Adjustments Page 1 of 33 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap. Design Last Name Yacht Name Record Date Base LP Adj Spin Rig Prop Rec Misc Race Cruise 12 Metre Gregory Valiant R060510 3 3 9 12 Metre Mc Millen 111 Onawa R012910 33 -6 27 33 30921 Pomfret Anne N061710 99 +9 108 108 5.5 Carney Lyric N071510 156 u156 u165 Abin Cumulus Bruen Cloud Dancer R062810 189 +9 +6 +6 210 216 Acrambault Paturel Ciao Bella R052510 36 -3 +3 +3 39 51 Aerodyne 38 D' Alessandro Alexis R031810 39 39 48 Aerodyne 38 Manchester Wazimo R051110 39 39 48 Aerodyne 43 Academy Tango N041310 12 12 21 Akilaria Class 40 Dreese Toothface R072210 -9 -9 0 Alberg 35 Prefontaine Helios R041110 201 -3 198 210 Albin Cumulus Droste Cumulus 3 R031110 189 189 204 Albin Nimbus 42 Stan Nimue N012310 99 -3 +6 102 114 Alden 40 Burt, Jr. Gitana R060510 171 171 177 Alden 44 Weisman Nostos R012710 111 +9 +6 126 132 Alerion 26 Hale Mischief R070510 225 U225 U231 Alerion 26 Loftus Sunny Side N122410 225 +6 231 246 Alerion 38-18 Stafford Alerion 38 N072210 111 111 120 Alerion Express 28 Brown Lumen Solare R032010 177 U177 U186 Alerion Express 28 Mac Kenzie Genevieve -

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes Installation Drawing Available Configuration May Be Boat-Dependent

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes installation drawing available Configuration may be boat-dependent BOAT MODEL SHAFT BRACKETS 7 Seas Sailer 37.5 ft ketch* M HE Able 42* M+5 HE Acadian 30* M HE Acapulco 40 (Islander) L HE Accent 28 S HE Accord 36 M HH Achilles 24 S HE Achilles 840 M EH Achilles 9m M EH Adams 35* M EH Adams 40 M HE Adams 45 M EH Adams 45/12.7T* X HH Afrodita 2 1/2 (Cal 2‐46)* X HE Alaska 42 L EH Alberg 29* M HE Alberg 30 M HE Alberg 34* M HE Alberg 35 S HE Alberg 37* M HE Albin Ballad* M EH Albin Vega* S HE Alden 42 yawl* S HA Alden 45/51* X HA Alden 50* X HE Alden 50* X+5 HA Alden Challenger 39* M HA Allegro 33 ‐ off center M HH Allen Pape 43* L HE Allied mistress MK III 42 ketch L HE Allied Princess* L HH Allied Seawind 32 Ketch* M HE Allures 45 S AH Älo 33* M EH Aloha 28* S EH Aloha 30* M EH Alpa 11.5* M EH Alubaat Ovni 495 S‐10 AH Aluboot BV L EH Aluminium 48 X HH Aluminum Peterson 44 racer X AH Amazon 37 L HA Amazon 37* L HE Amel 48 ketch X EH Amel 54 L AH Amel Euros 39* L HE Amel Euros 41* L HH Amel Mango* L HA Amel Maramu 46 and 48* L HH Amel Santorin X EH Amel Santorin 46 Ketch* L EH Amel Sharki 39 L EH Amel Sharki 39 M EH Amel Sharki 40 L EH Amel Sharki* L EH Amor 40* L HE Amphitrite 43/12T* X+15 HA Angleman Ketch* L HE Ankh 44* M HE Apache 41 L HH Aphrodite 36* L EH Aphrodite 40* L EH Aquarius 24 L HE Aquatelle 149 X HA Arcona 40 DS* L EH or AH Arcona 400 L HA Arpege M EH Arpege (non‐reverse transom)* L HH Athena 38 L AH Atlanta 26 (Viking)* M HE Atlanta 28 M EH Atlantic 36* X EH Atlantic 38 Power Ketch* L HE Atlantic -

11 Meter Od Odr *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48

11 METER OD ODR *(U)* 75 1D 35 36 1D 48 -42 30 SQUARE METER *(U)* 138 5.5 METER ODR *(U)* 156 6 METER ODR *(U)* Modern 108 6 METER ODR *(U)* Pre WW2 150 8 METER Modern 72 8 METER Pre WW2 111 ABBOTT 33 126 ABBOTT 36 102 ABLE 20 288 ABLE 42 141 ADHARA 30 90 AERODYNE 38 42 AERODYNE 38 CARBON 39 AERODYNE 43 12 AKILARIA class 40 RC1 -6/3 AKILARIA Class 40 RC2 -9/0 AKILARIA Class 40 RC3 -12/-3 ALAJUELA 33 198 ALAJUELA 38 216 ALBERG 29 225 ALBERG 30 228 ALBERG 35 201 ALBERG 37 YAWL 162 ALBIN 7.9 234 ALBIN BALLAD 30 186 ALBIN CUMULUS 189 ALBIN NIMBUS 42 99 ALBIN NOVA 33 159 ALBIN STRATUS 150 ALBIN VEGA 27 246 Alden 42 CARAVELLE 159 ALDEN 43 SD SM 120 ALDEN 44 111 ALDEN 44-2 105 ALDEN 45 87 ALDEN 46 84 ALDEN 54 57 ALDEN CHALLENGER 156 ALDEN DOLPHIN 126 ALDEN MALABAR JR 264 ALDEN PRISCILLA 228 ALDEN SEAGOER 141 ALDEN TRIANGLE 228 ALERION XPRS 20 *(U)* 249 ALERION XPRS 28 168 ALERION XPRS 28 WJ 180 ALERION XPRS 28-2 (150+) 165 ALERION XPRS 28-2 SD 171 ALERION XPRS 28-2 WJ 174 ALERION XPRS 33 120 ALERION XPRS 33 SD 132 ALERION XPRS 33 Sport 108 ALERION XPRS 38Y ODR 129 ALERION XPRS 38-2 111 ALERION XPRS 38-2 SD 117 ALERION 21 231 ALERION 41 99/111 ALLIED MISTRESS 39 186 ALLIED PRINCESS 36 210 ALLIED SEABREEZE 35 189 ALLIED SEAWIND 30 246 ALLIED SEAWIND 32 240 ALLIED XL2 42 138 ALLMAND 31 189 ALLMAND 35 156 ALOHA 10.4 162 ALOHA 30 144 ALOHA 32 171 ALOHA 34 162 ALOHA 8.5 198 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 120 AMEL SUPER MARAMU 2000 138 AMERICAN 17 *(U)* 216 AMERICAN 21 306 AMERICAN 26 288 AMF 2100 231 ANDREWS 26 144 ANDREWS 36 87 ANTRIM 27 87 APHRODITE 101 135 APHRODITE -

NEWS LETTER November 2009

NEWS LETTER November 2009 WESTERN SHORE ROUNDUP RECAP 2009 A bunch of Dickerson sailors had a great time from end to end in late September. It started with a proper Irish Bar Friday night aboard “Irish Mist”, and ended with the discovery of a missing ship’s cat Monday aboard Fahrmeier’s “Down Home”. In between, we had a boisterous race Saturday followed by the traditional cocktail party at West River Sailing Club and dinner at Pirates Cove. Once again, Joe Slavin won top honors in the race. We anticipated eight boats racing, but there were casualties. Bill Toth had to drop out Thursday because his Mom had a fall. Soon after the start, Dick Clarke had to drop out as his crew was showing significant signs of flu. Rick and Dottie Woytowich had to drop out with sail problems, and the Fahrmeiers dropped out late in the race due to fatigue and short crew. They had put 20 miles under the keel that day just getting to the racecourse, and it was blowing “pretty good”. Veteran ocean sailor, Bill Burry, showed a reef in his main before the start. A crewmember on “Irish Mist” (that would be me) tried to talk Joe out of raising the Mizzen, but to no avail. We got the race off, but unfortunately, my ineffective instructions and inexperience with the rabbit start of the fleet resulted in everyone except the rabbit getting a poor start. “Irish Mist”, the rabbit, was gone, and there was no catching her. With Barry Creighton and me continually flogging our skipper and ourselves, we amazingly made few mistakes, and we did a horizon job on the fleet. -

Club Hulls Oct 19, 2005

CLUB HULL LIST ORC Club “VPP Inside” October 2005 HULL TABLE INDEX There are several thousand hulls available in the following table, listed in alphabetic sequence by “Class Name” Navigation using the Acrobat index at the left or clicking an index entry below provides a short- cut to the corresponding section of the table. HULL TABLE EXPLANATIONS.........................................................2 NNUMERICUMERIC ................................................................................................3 ALPHA “A” ............................................................................................3 ALPHA “B” ............................................................................................4 ALPHA “C” ............................................................................................6 ALPHA “D”............................................................................................9 ALPHA “E” ..........................................................................................11 ALPHA “F” ..........................................................................................12 ALPHA “G”..........................................................................................15 ALPHA “H”..........................................................................................16 ALPHA “I” ...........................................................................................17 ALPHA “J”...........................................................................................18 ALPHA “K”