Classification of Magnetic Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arxiv:Cond-Mat/0106646 29 Jun 2001 Landau Diamagnetism Revisited

Landau Diamagnetism Revisited Sushanta Dattagupta†,**, Arun M. Jayannavar‡ and Narendra Kumar# †S.N. Bose National Centre for Basic Sciences, Block JD, Sector III, Salt Lake, Kolkata 700 098, India ‡Institute of Physics, Sachivalaya Marg, Bhubaneswar 751 005, India #Raman Research Institute, Bangalore 560 080, India The problem of diamagnetism, solved by Landau, continues to pose fascinating issues which have relevance even today. These issues relate to inherent quantum nature of the problem, the role of boundary and dissipation, the meaning of thermodynamic limits, and above all, the quantum–classical crossover occasioned by environment- induced decoherence. The Landau diamagnetism provides a unique paradigm for discussing these issues, the significance of which is far-reaching. Our central result connects the mean orbital magnetic moment, a thermodynamic property, with the electrical resistivity, which characterizes transport properties of material. In this communication, we wish to draw the attention of Peierls to term diamagnetism as one of the surprises in the reader to certain enigmatic issues concerning dia- theoretical physics4. Landau’s pathbreaking result also magnetism. Indeed, diamagnetism can be used as a demonstrated that the calculation of diamagnetic suscep- prototype phenomenon to illustrate the essential role of tibility did indeed require an explicit quantum treatment. quantum mechanics, surface–boundary, dissipation and Turning to the classical domain, two of the present nonequilibrium statistical mechanics itself. authors had worried, some years ago, about the issue: Diamagnetism is a material property that characterizes does the BV theorem survive dissipation5? This is a natu- the response of an ensemble of charged particles (more ral question to ask as dissipation is a ubiquitous property specifically, electrons) to an applied magnetic field. -

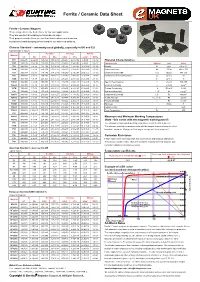

Ferrite / Ceramic Data Sheet

Ferrite / Ceramic Data Sheet Ferrite / Ceramic Magnets These magnets are the best choice for low cost applications. They are excellent at resisting corrosion due to water. Their properties make them an excellent choice when used in motors, loudspeakers and clamping devices and for use with reed switches. Chinese Standard - commonly used globally, especially in UK and EU Typical Range of Values Br Hc (Hcb) Hci (Hcj) BHmax Material mT kG kA/m kOe kA/m kOe kJ/m3 MGOe Y8T 200-235 2.0-2.35 125-160 1.57-2.01 210-280 2.64-3.52 6.5-9.5 0.8-1.2 Physical Characteristics Y10T 200-235 2.0-2.35 128-160 1.61-2.01 210-280 2.64-3.52 6.4-9.6 0.8-1.2 Characteristic Symbol Unit Value Y20 320-380 3.2-3.8 135-190 1.70-2.39 140-195 1.76-2.45 18.0-22.0 2.3-2.8 Density D g/cc 4.9 to 5.1 Y22H 310-360 3.1-3.6 220-250 2.76-3.14 280-320 3.52-4.02 20.0-24.0 2.5-3.0 Vickers Hardness Hv D.P.N 400 to 700 Y23 320-370 3.2-3.7 170-190 2.14-2.39 190-230 2.39-2.89 20.0-25.5 2.5-3.2 Compression Strength C.S N/mm2 680-720 Y25 360-400 3.6-4.0 135-170 1.70-2.14 140-200 1.76-2.51 22.5-28.0 2.8-3.5 Coefficient of Thermal Expansion C// 10-6/C 15 Y26H 360-390 3.6-3.9 220-250 2.76-3.14 225-255 2.83-3.20 23.0-28.0 2.9-3.5 C^ 10-6/C 10 Y26H-1 360-390 3.6-3.9 200-250 2.51-3.14 225-255 2.83-3.20 23.0-28.0 2.9-3.5 Specific Heat Capacity c J/kg°C 795-855 Y26H-2 360-380 3.6-3.8 263-288 3.30-3.62 318-350 4.00-4.40 24.0-28.0 3.0-3.5 Electrical Resistivity r m Ω.cm 1x1010 Y27H 370-400 3.7-4.0 205-250 2.58-3.14 210-255 2.64-3.20 25.0-29.0 3.1-3.6 Thermal Conductivity k W/cm°C 0.029 Y28 370-400 3.7-4.0 175-210 2.20-2.64 180-220 2.26-2.76 26.0-30.0 3.3-3.8 Modulus of Elasticity l / E Pa 1.8x1011 Y28H-1 380-400 3.8-4.0 240-260 3.02-3.27 250-280 3.14-3.52 27.0-30.0 3.4-3.8 Compression Strength C.S. -

Canted Ferrimagnetism and Giant Coercivity in the Non-Stoichiometric

Canted ferrimagnetism and giant coercivity in the non-stoichiometric double perovskite La2Ni1.19Os0.81O6 Hai L. Feng1, Manfred Reehuis2, Peter Adler1, Zhiwei Hu1, Michael Nicklas1, Andreas Hoser2, Shih-Chang Weng3, Claudia Felser1, Martin Jansen1 1Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids, Dresden, D-01187, Germany 2Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin für Materialien und Energie, Berlin, D-14109, Germany 3National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (NSRRC), Hsinchu, 30076, Taiwan Abstract: The non-stoichiometric double perovskite oxide La2Ni1.19Os0.81O6 was synthesized by solid state reaction and its crystal and magnetic structures were investigated by powder x-ray and neutron diffraction. La2Ni1.19Os0.81O6 crystallizes in the monoclinic double perovskite structure (general formula A2BB’O6) with space group P21/n, where the B site is fully occupied by Ni and the B’ site by 19 % Ni and 81 % Os atoms. Using x-ray absorption spectroscopy an Os4.5+ oxidation state was established, suggesting presence of about 50 % 5+ 3 4+ 4 paramagnetic Os (5d , S = 3/2) and 50 % non-magnetic Os (5d , Jeff = 0) ions at the B’ sites. Magnetization and neutron diffraction measurements on La2Ni1.19Os0.81O6 provide evidence for a ferrimagnetic transition at 125 K. The analysis of the neutron data suggests a canted ferrimagnetic spin structure with collinear Ni2+ spin chains extending along the c axis but a non-collinear spin alignment within the ab plane. The magnetization curve of La2Ni1.19Os0.81O6 features a hysteresis with a very high coercive field, HC = 41 kOe, at T = 5 K, which is explained in terms of large magnetocrystalline anisotropy due to the presence of Os ions together with atomic disorder. -

Unerring in Her Scientific Enquiry and Not Afraid of Hard Work, Marie Curie Set a Shining Example for Generations of Scientists

Historical profile Elements of inspiration Unerring in her scientific enquiry and not afraid of hard work, Marie Curie set a shining example for generations of scientists. Bill Griffiths explores the life of a chemical heroine SCIENCE SOURCE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY LIBRARY PHOTO SCIENCE / SOURCE SCIENCE 42 | Chemistry World | January 2011 www.chemistryworld.org On 10 December 1911, Marie Curie only elements then known to or ammonia, having a water- In short was awarded the Nobel prize exhibit radioactivity. Her samples insoluble carbonate akin to BaCO3 in chemistry for ‘services to the were placed on a condenser plate It is 100 years since and a chloride slightly less soluble advancement of chemistry by the charged to 100 Volts and attached Marie Curie became the than BaCl2 which acted as a carrier discovery of the elements radium to one of Pierre’s electrometers, and first person ever to win for it. This they named radium, and polonium’. She was the first thereby she measured quantitatively two Nobel prizes publishing their results on Boxing female recipient of any Nobel prize their radioactivity. She found the Marie and her husband day 1898;2 French spectroscopist and the first person ever to be minerals pitchblende (UO2) and Pierre pioneered the Eugène-Anatole Demarçay found awarded two (she, Pierre Curie and chalcolite (Cu(UO2)2(PO4)2.12H2O) study of radiactivity a new atomic spectral line from Henri Becquerel had shared the to be more radioactive than pure and discovered two new the element, helping to confirm 1903 physics prize for their work on uranium, so reasoned that they must elements, radium and its status. -

Magnetism, Magnetic Properties, Magnetochemistry

Magnetism, Magnetic Properties, Magnetochemistry 1 Magnetism All matter is electronic Positive/negative charges - bound by Coulombic forces Result of electric field E between charges, electric dipole Electric and magnetic fields = the electromagnetic interaction (Oersted, Maxwell) Electric field = electric +/ charges, electric dipole Magnetic field ??No source?? No magnetic charges, N-S No magnetic monopole Magnetic field = motion of electric charges (electric current, atomic motions) Magnetic dipole – magnetic moment = i A [A m2] 2 Electromagnetic Fields 3 Magnetism Magnetic field = motion of electric charges • Macro - electric current • Micro - spin + orbital momentum Ampère 1822 Poisson model Magnetic dipole – magnetic (dipole) moment [A m2] i A 4 Ampere model Magnetism Microscopic explanation of source of magnetism = Fundamental quantum magnets Unpaired electrons = spins (Bohr 1913) Atomic building blocks (protons, neutrons and electrons = fermions) possess an intrinsic magnetic moment Relativistic quantum theory (P. Dirac 1928) SPIN (quantum property ~ rotation of charged particles) Spin (½ for all fermions) gives rise to a magnetic moment 5 Atomic Motions of Electric Charges The origins for the magnetic moment of a free atom Motions of Electric Charges: 1) The spins of the electrons S. Unpaired spins give a paramagnetic contribution. Paired spins give a diamagnetic contribution. 2) The orbital angular momentum L of the electrons about the nucleus, degenerate orbitals, paramagnetic contribution. The change in the orbital moment -

Magnetic Fields Magnetism Magnetic Field

PHY2061 Enriched Physics 2 Lecture Notes Magnetic Fields Magnetic Fields Disclaimer: These lecture notes are not meant to replace the course textbook. The content may be incomplete. Some topics may be unclear. These notes are only meant to be a study aid and a supplement to your own notes. Please report any inaccuracies to the professor. Magnetism Is ubiquitous in every-day life! • Refrigerator magnets (who could live without them?) • Coils that deflect the electron beam in a CRT television or monitor • Cassette tape storage (audio or digital) • Computer disk drive storage • Electromagnet for Magnetic Resonant Imaging (MRI) Magnetic Field Magnets contain two poles: “north” and “south”. The force between like-poles repels (north-north, south-south), while opposite poles attract (north-south). This is reminiscent of the electric force between two charged objects (which can have positive or negative charge). Recall that the electric field was invoked to explain the “action at a distance” effect of the electric force, and was defined by: F E = qel where qel is electric charge of a positive test charge and F is the force acting on it. We might be tempted to define the same for the magnetic field, and write: F B = qmag where qmag is the “magnetic charge” of a positive test charge and F is the force acting on it. However, such a single magnetic charge, a “magnetic monopole,” has never been observed experimentally! You cannot break a bar magnet in half to get just a north pole or a south pole. As far as we know, no such single magnetic charges exist in the universe, D. -

Density of States Information from Low Temperature Specific Heat

JOURNAL OF RESE ARC H of th e National Bureau of Standards - A. Physics and Chemistry Val. 74A, No.3, May-June 1970 Density of States I nformation from Low Temperature Specific Heat Measurements* Paul A. Beck and Helmut Claus University of Illinois, Urbana (October 10, 1969) The c a lcul ati on of one -electron d ensit y of s tate va lues from the coeffi cient y of the te rm of the low te mperature specifi c heat lin ear in te mperature is compli cated by many- body effects. In parti c ul ar, the electron-p honon inte raction may enhance the measured y as muc h as tw ofo ld. The e nha nce me nt fa ctor can be eva luat ed in the case of supe rconducting metals and a ll oys. In the presence of magneti c mo ments, add it ional complicati ons arise. A magneti c contribution to the measured y was ide ntifi e d in the case of dilute all oys and a lso of concentrated a lJ oys wh e re parasiti c antife rromagnetis m is s upe rim posed on a n over-a ll fe rromagneti c orde r. No me thod has as ye t bee n de vised to e valu ate this magne ti c part of y. T he separati on of the te mpera ture- li near term of the s pec ifi c heat may itself be co mpli cated by the a ppearance of a s pecific heat a no ma ly due to magneti c cluste rs in s upe rpa ramagneti c or we ak ly ferromagneti c a ll oys. -

Unusual Quantum Criticality in Metals and Insulators T. Senthil (MIT)

Unusual quantum criticality in metals and insulators T. Senthil (MIT) T. Senthil, ``Critical fermi surfaces and non-fermi liquid metals”, PR B, June 08 T. Senthil, ``Theory of a continuous Mott transition in two dimensions”, PR B, July 08 D. Podolsky, A. Paramekanti, Y.B. Kim, and T. Senthil, ``Mott transition between a spin liquid insulator and a metal in three dimensions”, PRL, May 09 T. Senthil and P. A. Lee, ``Coherence and pairing in a doped Mott insulator: Application to the cuprates”, PRL, Aug 09 Precursors: T. Senthil, Annals of Physics, ’06, T. Senthil. M. Vojta, S. Sachdev, PR B, ‘04 Saturday, October 22, 2011 High Tc cuprates: doped Mott insulators Many interesting phenomena on doping the Mott insulator: Loss of antiferromagnetism High Tc superconductivity Pseudogaps, non-fermi liquid regimes , etc. Stripes, nematics, and other broken symmetries This talk: focus on one (among many) fundamental question. How does a Fermi surface emerge when a Mott insulator changes into a metal? Saturday, October 22, 2011 High Tc cuprates: how does a Fermi surface emerge from a doped Mott insulator? Evolution from Mott insulator to overdoped metal : emergence of large Fermi surface with area set by usual Luttinger count. Mott insulator: No Fermi surface Overdoped metal: Large Fermi surface ADMR, quantum oscillations (Hussey), ARPES (Damascelli,….) Saturday, October 22, 2011 High Tc cuprates: how does a Fermi surface emerge from a doped Mott insulator? Large gapless Fermi surface present even in optimal doped strange metal albeit without Landau quasiparticles . Mott insulator: No Fermi surface Saturday, October 22, 2011 High Tc cuprates: how does a Fermi surface emerge from a doped Mott insulator? Large gapless Fermi surface present also in optimal doped strange metal albeit without Landau quasiparticles . -

A TWO DIMENSIONAL FERRITE-CORE MEMORY Bv M

A TWO DIMENSIONAL FERRITE-CORE MEMORY Bv M. M. FAROOQUI, S. P. SKiVASTAVA AND R. N. NEOGI (Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Bomba),) Received January t0, 1957 (Communicated by Prof. Bernard P ABS'IXACT This paper describes a two dimensional matrix memory using ferrite- cores. A urtit consisting of 100 words of I 1 binary digits each has been cortstructed for parallel operation. The word drive is from a biasr switch-core matrix, while the digit drive makes use of pulse--trans- formers. Logic and circuit techniques enable high discrimination bet- ween wanted and unwanted signals. A semi-automatic method for testing the memory cores is also described. INTRODUCTION THE potentiality of magnetie fer¡ with a rectangular hysteresis loop as binary storage elements for digital computer was realised earlier by Forrester. x Later, Papian% s and almost simultaneously Rajchman4, ~ showed the practicability of such a system by successfully operating memories of fairly large capacity. This paper describes a modest attempt in this direction. A memory of I00 words, 11 bits each, has beca constructed to operate with a smaU digital computer at the Tata institute of Fundamental Research, Bombay. THE PRINClPLE OF OPERATION OF THE MEMORY The two stable states required for sto¡ binary information in magnetic cores ate the states of positive and negative magnetisation. These are the states corresponding to the position A0 and Ax on the hysteresis loop and can be termed as the 0- and the 1-states respectively (Fig. 2). Con- sider a number of sucia cores with ah ideaUy rectangular hysteresis character- istic, arranged in rows and columns in the form of a matrix. -

Chapter 6 Antiferromagnetism and Other Magnetic Ordeer

Chapter 6 Antiferromagnetism and Other Magnetic Ordeer 6.1 Mean Field Theory of Antiferromagnetism 6.2 Ferrimagnets 6.3 Frustration 6.4 Amorphous Magnets 6.5 Spin Glasses 6.6 Magnetic Model Compounds TCD February 2007 1 1 Molecular Field Theory of Antiferromagnetism 2 equal and oppositely-directed magnetic sublattices 2 Weiss coefficients to represent inter- and intra-sublattice interactions. HAi = n’WMA + nWMB +H HBi = nWMA + n’WMB +H Magnetization of each sublattice is represented by a Brillouin function, and each falls to zero at the critical temperature TN (Néel temperature) Sublattice magnetisation Sublattice magnetisation for antiferromagnet TCD February 2007 2 Above TN The condition for the appearance of spontaneous sublattice magnetization is that these equations have a nonzero solution in zero applied field Curie Weiss ! C = 2C’, P = C’(n’W + nW) TCD February 2007 3 The antiferromagnetic axis along which the sublattice magnetizations lie is determined by magnetocrystalline anisotropy Response below TN depends on the direction of H relative to this axis. No shape anisotropy (no demagnetizing field) TCD February 2007 4 Spin Flop Occurs at Hsf when energies of paralell and perpendicular configurations are equal: HK is the effective anisotropy field i 1/2 This reduces to Hsf = 2(HKH ) for T << TN Spin Waves General: " n h q ~ q ! M and specific heat ~ Tq/n Antiferromagnet: " h q ~ q ! M and specific heat ~ Tq TCD February 2007 5 2 Ferrimagnetism Antiferromagnet with 2 unequal sublattices ! YIG (Y3Fe5O12) Iron occupies 2 crystallographic sites one octahedral (16a) & one tetrahedral (24d) with O ! Magnetite(Fe3O4) Iron again occupies 2 crystallographic sites one tetrahedral (8a – A site) & one octahedral (16d – B site) 3 Weiss Coefficients to account for inter- and intra-sublattice interaction TCD February 2007 6 Below TN, magnetisation of each sublattice is zero. -

Coexistence of Superparamagnetism and Ferromagnetism in Co-Doped

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Scripta Materialia 69 (2013) 694–697 www.elsevier.com/locate/scriptamat Coexistence of superparamagnetism and ferromagnetism in Co-doped ZnO nanocrystalline films Qiang Li,a Yuyin Wang,b Lele Fan,b Jiandang Liu,a Wei Konga and Bangjiao Yea,⇑ aState Key Laboratory of Particle Detection and Electronics, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, People’s Republic of China bNational Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230029, People’s Republic of China Received 8 April 2013; revised 5 August 2013; accepted 6 August 2013 Available online 13 August 2013 Pure ZnO and Zn0.95Co0.05O films were deposited on sapphire substrates by pulsed-laser deposition. We confirm that the magnetic behavior is intrinsic property of Co-doped ZnO nanocrystalline films. Oxygen vacancies play an important mediation role in Co–Co ferromagnetic coupling. The thermal irreversibility of field-cooling and zero field-cooling magnetizations reveals the presence of superparamagnetic behavior in our films, while no evidence of metallic Co clusters was detected. The origin of the observed superparamagnetism is discussed. Ó 2013 Acta Materialia Inc. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Dilute magnetic semiconductors; Superparamagnetism; Ferromagnetism; Co-doped ZnO Dilute magnetic semiconductors (DMSs) have magnetic properties in this system. In this work, the cor- attracted increasing attention in the past decade due to relation between the structural features and magnetic their promising technological applications in the field properties of Co-doped ZnO films was clearly of spintronic devices [1]. Transition metal (TM)-doped demonstrated. ZnO is one of the most attractive DMS candidates The Zn0.95Co0.05O films were deposited on sapphire because of its outstanding properties, including room- (0001) substrates by pulsed-laser deposition using a temperature ferromagnetism. -

Solid State Physics 2 Lecture 5: Electron Liquid

Physics 7450: Solid State Physics 2 Lecture 5: Electron liquid Leo Radzihovsky (Dated: 10 March, 2015) Abstract In these lectures, we will study itinerate electron liquid, namely metals. We will begin by re- viewing properties of noninteracting electron gas, developing its Greens functions, analyzing its thermodynamics, Pauli paramagnetism and Landau diamagnetism. We will recall how its thermo- dynamics is qualitatively distinct from that of a Boltzmann and Bose gases. As emphasized by Sommerfeld (1928), these qualitative di↵erence are due to the Pauli principle of electons’ fermionic statistics. We will then include e↵ects of Coulomb interaction, treating it in Hartree and Hartree- Fock approximation, computing the ground state energy and screening. We will then study itinerate Stoner ferromagnetism as well as various response functions, such as compressibility and conduc- tivity, and screening (Thomas-Fermi, Debye). We will then discuss Landau Fermi-liquid theory, which will allow us understand why despite strong electron-electron interactions, nevertheless much of the phenomenology of a Fermi gas extends to a Fermi liquid. We will conclude with discussion of electrons on the lattice, treated within the Hubbard and t-J models and will study transition to a Mott insulator and magnetism 1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Outline electron gas ground state and excitations • thermodynamics • Pauli paramagnetism • Landau diamagnetism • Hartree-Fock theory of interactions: ground state energy • Stoner ferromagnetic instability • response functions • Landau Fermi-liquid theory • electrons on the lattice: Hubbard and t-J models • Mott insulators and magnetism • B. Background In these lectures, we will study itinerate electron liquid, namely metals. In principle a fully quantum mechanical, strongly Coulomb-interacting description is required.