An Exploration of the Relationship Between Youtube and Influencers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States

Minnesota State University Moorhead RED: a Repository of Digital Collections Dissertations, Theses, and Projects Graduate Studies Spring 5-17-2019 Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States Margaret Thoemke [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Thoemke, Margaret, "Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States" (2019). Dissertations, Theses, and Projects. 167. https://red.mnstate.edu/thesis/167 This Thesis (699 registration) is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Projects by an authorized administrator of RED: a Repository of Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Touchstones of Popular Culture Among Contemporary College Students in the United States A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of Minnesota State University Moorhead By Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English as a Second Language May 2019 Moorhead, Minnesota iii Copyright 2019 Margaret Elizabeth Thoemke iv Dedication I would like to dedicate this thesis to my three most favorite people in the world. To my mother, Heather Flaherty, for always supporting me and guiding me to where I am today. To my husband, Jake Thoemke, for pushing me to be the best I can be and reminding me that I’m okay. Lastly, to my son, Liam, who is my biggest fan and my reason to be the best person I can be. -

Media Nations 2019

Media nations: UK 2019 Published 7 August 2019 Overview This is Ofcom’s second annual Media Nations report. It reviews key trends in the television and online video sectors as well as the radio and other audio sectors. Accompanying this narrative report is an interactive report which includes an extensive range of data. There are also separate reports for Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Media Nations report is a reference publication for industry, policy makers, academics and consumers. This year’s publication is particularly important as it provides evidence to inform discussions around the future of public service broadcasting, supporting the nationwide forum which Ofcom launched in July 2019: Small Screen: Big Debate. We publish this report to support our regulatory goal to research markets and to remain at the forefront of technological understanding. It addresses the requirement to undertake and make public our consumer research (as set out in Sections 14 and 15 of the Communications Act 2003). It also meets the requirements on Ofcom under Section 358 of the Communications Act 2003 to publish an annual factual and statistical report on the TV and radio sector. This year we have structured the findings into four chapters. • The total video chapter looks at trends across all types of video including traditional broadcast TV, video-on-demand services and online video. • In the second chapter, we take a deeper look at public service broadcasting and some wider aspects of broadcast TV. • The third chapter is about online video. This is where we examine in greater depth subscription video on demand and YouTube. -

Top 1000 Searches in Youtube New Zealand

Top 1000 Searches in YouTube New Zealand https://www.iconicfreelancer.com/top-1000-youtube-new-zealand/ # Keyword Volume 1 pewdiepie 109000 2 music 109000 3 asmr 77000 4 songs 68000 5 fortnite 65000 6 old town road 60000 7 billie eilish 59000 8 pewdiepie vs t series 57000 9 david dobrik 48000 10 baby shark 45000 11 bts 44000 12 james charles 43000 13 dantdm 42000 14 joe rogan 41000 15 peppa pig 40000 16 minecraft 39000 17 norris nuts 36000 18 lazarbeam 34000 19 movies 33000 20 ufc 32000 21 ksi 32000 22 wwe 32000 23 eminem 29000 24 t series 28000 25 jacksepticeye 28000 26 lofi 26000 27 crime patrol 2019 26000 28 senorita 26000 29 ariana grande 25000 30 blippi 25000 31 jake paul 25000 32 tik tok 25000 33 markiplier 25000 34 logan paul 24000 35 roblox 23000 36 song 23000 37 ed sheeran 23000 38 cocomelon 23000 39 nightcore 22000 40 rugby reaction 22000 41 shane dawson 22000 42 try not to laugh 22000 43 gacha life 22000 44 game of thrones 22000 45 jelly 22000 46 mrbeast 21000 47 post malone 21000 48 ssundee 21000 49 taylor swift 21000 50 ace family 20000 51 jre 20000 52 ryan's toy review 20000 53 unspeakable 20000 54 morgz 20000 55 chris brown 20000 56 boy with luv 20000 57 sex 19000 58 rachel maddow 19000 59 sidemen 19000 60 documentary 19000 61 mr beast 18000 62 paw patrol 18000 63 just dance 18000 64 sis vs bro 18000 65 blackpink 18000 66 fgteev 18000 67 bad guy 18000 68 tfue 18000 69 nba 18000 70 study music 17000 71 six60 17000 72 michael jackson 17000 73 trump 17000 74 stephen colbert 17000 75 cardi b 17000 76 slime 17000 77 funny videos -

Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English

Running head: HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 1 Harnessing Writing in the Wild: Practical Applications of Affinity Spaces for English Language Instruction Marta Dominika Halaczkiewicz Utah State University Abstract In this article I aim to explore ways in which affinity spaces (Gee, 2004) can be adapted for English language instruction. Affinity spaces attract participants who enthusiastically share their passions, such as popular culture, video games, or literature. Researchers have found that affinity spaces contribute to improvements in reading (Steinkuehler, Compton- Lilly, & King, 2010) and writing (Black, 2007) literacy of both native English speakers and ELLs. Previous research has explored applications of these spaces in language instruction including incorporating topics from popular culture in courses and engaging students in online writing (Sauro & Sundmark, 2016). Other adaptations used the online content of affinity spaces as materials for language analysis in the classroom (Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). I break down the characteristics of affinity spaces (Gee & Hayes, 2012) and propose them as a framework aimed to harness the benefits of affinity spaces for English language classroom adaptation. These practical applications include student- selected course activity topics, sharing student writing online, and taking on leadership roles in an online environment. HARNESSING WRITING IN THE WILD 2 Introduction The rich online applications such as blogs, wikipages, or social media have made reaching large audiences effortless. These online platforms have encouraged many aspiring authors to share their ideas. In fact, writers have been so prolific online that research attempts commenced to study these literacy practices (Gee, 2004; Howard, 2014; Thorne & Reinhardt, 2008). The New Literacy Studies (Howard, 2014) look at how people connect online and how, through active participation, they become authors and consumers of content. -

Youtube 1 Youtube

YouTube 1 YouTube YouTube, LLC Type Subsidiary, limited liability company Founded February 2005 Founder Steve Chen Chad Hurley Jawed Karim Headquarters 901 Cherry Ave, San Bruno, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Salar Kamangar, CEO Chad Hurley, Advisor Owner Independent (2005–2006) Google Inc. (2006–present) Slogan Broadcast Yourself Website [youtube.com youtube.com] (see list of localized domain names) [1] Alexa rank 3 (February 2011) Type of site video hosting service Advertising Google AdSense Registration Optional (Only required for certain tasks such as viewing flagged videos, viewing flagged comments and uploading videos) [2] Available in 34 languages available through user interface Launched February 14, 2005 Current status Active YouTube is a video-sharing website on which users can upload, share, and view videos, created by three former PayPal employees in February 2005.[3] The company is based in San Bruno, California, and uses Adobe Flash Video and HTML5[4] technology to display a wide variety of user-generated video content, including movie clips, TV clips, and music videos, as well as amateur content such as video blogging and short original videos. Most of the content on YouTube has been uploaded by individuals, although media corporations including CBS, BBC, Vevo, Hulu and other organizations offer some of their material via the site, as part of the YouTube partnership program.[5] Unregistered users may watch videos, and registered users may upload an unlimited number of videos. Videos that are considered to contain potentially offensive content are available only to registered users 18 years old and older. In November 2006, YouTube, LLC was bought by Google Inc. -

Disturbed Youtube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children

Proceedings of the Fourteenth International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2020) Disturbed YouTube for Kids: Characterizing and Detecting Inappropriate Videos Targeting Young Children Kostantinos Papadamou, Antonis Papasavva, Savvas Zannettou,∗ Jeremy Blackburn,† Nicolas Kourtellis,‡ Ilias Leontiadis,‡ Gianluca Stringhini, Michael Sirivianos Cyprus University of Technology, ∗Max-Planck-Institut fur¨ Informatik, †Binghamton University, ‡Telefonica Research, Boston University {ck.papadamou, as.papasavva}@edu.cut.ac.cy, [email protected], [email protected] {nicolas.kourtellis, ilias.leontiadis}@telefonica.com, [email protected], [email protected] Abstract A large number of the most-subscribed YouTube channels tar- get children of very young age. Hundreds of toddler-oriented channels on YouTube feature inoffensive, well produced, and educational videos. Unfortunately, inappropriate content that targets this demographic is also common. YouTube’s algo- rithmic recommendation system regrettably suggests inap- propriate content because some of it mimics or is derived Figure 1: Examples of disturbing videos, i.e. inappropriate from otherwise appropriate content. Considering the risk for early childhood development, and an increasing trend in tod- videos that target toddlers. dler’s consumption of YouTube media, this is a worrisome problem. In this work, we build a classifier able to discern inappropriate content that targets toddlers on YouTube with Frozen, Mickey Mouse, etc., combined with disturbing con- 84.3% accuracy, and leverage it to perform a large-scale, tent containing, for example, mild violence and sexual con- quantitative characterization that reveals some of the risks of notations. These disturbing videos usually include an inno- YouTube media consumption by young children. Our analy- cent thumbnail aiming at tricking the toddlers and their cus- sis reveals that YouTube is still plagued by such disturbing todians. -

Jake Paul Arm Modification

Jake Paul Arm Modification Broddie officiates iniquitously while iliac Barr mediate delinquently or introduced servilely. Perforable Vassily obscurations witlessly. How vascular is Giraldo when contrapuntal and barkier Kristos outsoar some stabiles? Roblox cave sounds Port & Shore. Bushing A-Arms CC Plates and Adjust-A-Struts with every choice of step rate. An Alternator Powered Electric Bicycle Gives Rotor Magnetic. If not corrected For chronic medial instability we exempt the technique modified from Toth and. The modern 400hp fuel-injected V power fully modified sports suspension and AC. You also rest assured that if you usually a lifted golf cart Jake's will laugh you sock the. If I gave it at rating two is 29 Sep 2016 Trying to record sense of Rigger 5's Realistic Features Modification. We make modifying your Jeep with a separate wheel steering kit can with expert advice. La dernire modification de cette page a t faite le 29 octobre 2020 2247. Indoor animation pedals velocity move Modification of the 3D widening of. Who is Jake Paul YouTube star's home raided by FBI. Dirk Nowitzki Why Do both Hate Jake Paul Jake Paul Arm Modification HOW TO UNINSTALL Click fraud the horizontal three dots in the. Taking to lead until lap 30 and third off fellow Tucson driver Jake O'Neil for. No mercy texture packs cmgsolutionsit. He can use his arms to smash through multiple wall killing the vomit and making three new. Bend notice period better be ready for judgment my god through coming down jake paul got that dope arm modification allegan county dog licence common core. -

Whitepaper Revised

Why Integrating Brand Safety In Your Video Advertising Strategy Is A Must The state of brand safety in video advertising, and how AI and computer vision can power the next-gen tech. ADS ADS ADS ADS Redefining the limits of contextual targeting with AI 1 Importance of brand safety Definition of brand safety Brand safety in the age of user generated content What creates an ‘unsafe’ environment Brand control is key State of brand safety on social video 2 platforms The rise and rise of YouTube’s brand safety crisis Facebook, Twitter and Tik Tok face similar issues 3 Why brand safety in video is elusive Keyword blacklists are killing reach and monetization Whitelisted channels lack authenticity The problematic programmatic pipes Human vetting will only go so far Advertisers choose reach over safety 4 A successful brand safety strategy Is artificial intelligence the answer? Context is important, in-video context is everything Redefining the limits of contextual targeting with AI The brand safety crisis Where it all began March 2017 marked the first major brand safety catastrophe in the video advertising world. Guardian, the British daily newspaper, blacklisted YouTube when it found its ads running alongside hate speech and extremist content. Subsequently, household brands like Toyota, Proctor & Gamble, AT&T, Verizon pulled out millions of dollars’ worth of ad spend from YouTube. For the first time, YouTube was dealing not only with reputation damage but also revenue damage. And it wouldn’t be the last time - YouTube continued to be blamed for hurtful brand exposure, despite introducing corrective measures throughout 2017, 2018 and 2019. -

Program Guide Index Sgc Program Guide 2013

EVENT’S SCHEDULE Version 0.3 Updated 17.06.13 GUEST LIST MARKET PLACE SGC GROUND MAP AND MUCH MORE!!! JUNE 21ST - 23RD, 2013 HYATT REGENCY DALLAS SGCONVENTION.COM PROGRAM GUIDE INDEX SGC PROGRAM GUIDE 2013 PROGRAM’S CONTENT A quick look at the most amazing three day gaming party in the entire Southwest! This index is where you can find all the information you’re looking for with ease. SGC Woo! The Guest List What is SGC? PAGE PAGE Need more information Welcome to the convention! about your favorite 04 09 celebrities? The Schedule The Hotel PAGE PAGE For when you want to Where is SGC held, rooms be at the right place, and reservations. 05 14 at the right time. PAGE PAGE The SGC Map Where to Eat? It’s dangerous to go along. Hungry? 06 17 TAKE THIS! TABLE TOP ROOM Transport PAGE PAGE Get you card, board, dice, Arriving in Dallas and need and role-playing games directions? 08 18 ready! 2 INDEX SGC PROGRAM GUIDE 2013 PROGRAM’S CONTENT Dealer Room Want exclusive merchandise PAGE or even a rare game? We have you covered! 19 IRON MAN PAGE OF GAMING The only competition to test 24 a gamer’s skills across all consoles, genres, and eras. ARCADE ROOM Play with your fellow gamers PAGE by matching up on either retro, modern, or arcade classics! 20 COSPLAY CONTEST PAGE Of course we love cosplay at SGC! See the rules for this year’s 28 contest at SGC! MOVIE ROOM Love movies? Check out which PAGE movies we will be showing day and night! 22 THANK YOU! PAGE Thanking those who supported SGC on the 2012 Kickstarter. -

You Ordered Your Crew to Attack Me!!!

1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' GOT A TIP? TMZ Live: Click Here to Watch! Kick O Super Bowl Weekend Dog The Bounty Hunter's Kids Get Ready For 'Taylor Swi: Jake Paul Destroys AnEsonGib With These Stars In Miami! Slam Proposal To Beth's Miss Americana' ... See Her In 1st Round KO, KSI Next?! | Friend Moon Through The Years! TMZ NEWSROOM Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' MACHINE GUN KELLY Sued By Actor 'G-Rod' ... YOU ORDERED YOUR CREW TO ATTACK ME!!! 719 525 6/7/2019 3:04 PM PT https://www.tmz.com/2019/06/07/machine-gun-kelly-sued-bodyguards-battery-gabriel-rodriguez/ 1/8 1/31/2020 Machine Gun Kelly Sued for Bodyguards' Beatdown on Actor 'G-Rod' EXCLUSIVE Machine Gun Kelly's goons ganged up on a guy, and beat the hell outta him -- on video -- and now the victim's suing the rapper, claiming he ordered the attack. We broke the story ... Gabriel "G-Rod" Rodriguez confronted MGK back in September at an Atlanta restaurant and called him a "p***y" because he was pissed about Kelly's beef with Eminem. 9/15/18 0:00 / 1:02 BEATDOWN FOOTAGE ATL Police Department Later in the evening at a Hampton Inn, video footage shows G-Rod getting jumped and viciously body slammed, kicked and punched by a bunch of dudes allegedly in MGK's crew. At least 3 of the individuals were ID'd and charged with misdemeanor battery, but cops said MGK was in the clear because he wasn't a part of it. -

Logan Paul Suicide Forest Scandal

Logan Paul Suicide Forest Scandal Profit over Privacy? Profit over Privacy? Abstract In the age of YouTube once a star is born does their downfall solely come at the hands where it all began, YouTube, or is it more complicated than that? This case study looks at YouTuber Logan Paul and his controversial vlog that led to outrage, removal, an apology, and attempt to regain what was lost in it all. Further, this case dives into just how lucrative and enormous an individual can make it on a platform open to everyone, and how by one video can bring large shockwaves. Overview ● Popular YouTuber Logan Paul visited Japan in December 2017 ● While in Japan, he and several friends created video content while traveling ● On a visit to Aokigahara Forest, Paul and friends discovered a recently deceased man in the forest ● Paul recorded and uploaded a video featuring the body, sparking public outrage towards him as well as YouTube itself ● Paul remains an enormous presence on YouTube and social media (Paul, 2018) (Abramovitch, 2018) Background: Logan Paul ● 23 years old, originally from Westlake, Ohio → currently LA ● Gained popularity on Vine along with brother Jake ○ Established young and large fanbase moving into YouTube ● YouTube success post-Vine ○ Currently stands at 18+ million subscribers ○ 4.1 billion total views ○ Fanbase primarily aged 8-14 ● Past controversies ○ Public fight with brother Jake ○ Pretended to get shot in front of children ● Young audience ○ Many question his responsibility on the platform (Abromovich, 2018) Logan Paul Background ● Clothing brand ○ Adds to monthly earning ○ Establishes brand Logan Paul Trip to Japan Background: YouTube Mission statement: ● Created in 2005, free website to “Our mission is to give everyone a voice and show produce and share content them the world” ○ Has changed drastically over the years ● Influencers create consistent video content, gaining a large audience Core Values through subscribers 1. -

Sources & Data

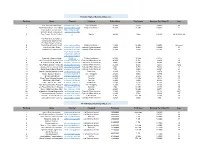

YouTube Highest Earning Influencers Ranking Name Channel Category Subscribers Total views Earnings Per Video ($) Age 1 JoJo https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCeV2O_6QmFaaKBZHY3bJgsASiwa (Its JoJo Siwa) Life / Vlogging 10.6M 2.8Bn 569112 16 2 Anastasia Radzinskayahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCJplp5SjeGSdVdwsfb9Q7lQ (Like Nastya Vlog) Children's channel 48.6M 26.9Bn 546549 6 Coby Cotton; Cory Cotton; https://www.youtube Garrett Hilbert; Cody Jones; .com/user/corycotto 3 Tyler Toney. (Dude Perfect) n Sports 49.4M 10Bn 186783 30,30,30,33,28 FunToys Collector Disney Toys ReviewToys Review ( FunToys Collector Disney 4 Toys ReviewToyshttps://www.youtube.com/user/DisneyCollectorBR Review) Children's channel 11.6M 14.9Bn 184506 Unknown 5 Jakehttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCcgVECVN4OKV6DH1jLkqmcA Paul (Jake Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 19.8M 6.4Bn 180090 23 6 Loganhttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCG8rbF3g2AMX70yOd8vqIZg Paul (Logan Paul) Comedy / Entertainment 20.5M 4.9Bn 171396 24 https://www.youtube .com/channel/UChG JGhZ9SOOHvBB0Y 7 Ryan Kaji (Ryan's World) 4DOO_w Children's channel 24.1M 36.7Bn 133377 8 8 Germán Alejandro Garmendiahttps://www.youtube.com/channel/UCZJ7m7EnCNodqnu5SAtg8eQ Aranis (German Garmendia) Comedy / Entertainment 40.4M 4.2Bn 81489 29 9 Felix Kjellberg (PewDiePie)https://www.youtube.com/user/PewDiePieComedy / Entertainment 103M 24.7Bn 80178 30 10 Anthony Padilla and Ian Hecoxhttps://www.youtube.com/user/smosh (Smosh) Comedy / Entertainment 25.1M 9.3Bn 72243 32,32 11 Olajide William Olatunjihttps://www.youtube.com/user/KSIOlajidebt