The English Trade in Nightingales Ingeborg Zechner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

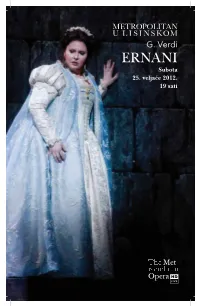

ERNANI Web.Pdf

Foto: Metropolitan opera G. Verdi ERNANI Subota, 25. veljae 2012., 19 sati THE MET: LIVE IN HD SERIES IS MADE POSSIBLE BY A GENEROUS GRANT FROM ITS FOUNDING SPONZOR Neubauer Family Foundation GLOBAL CORPORATE SPONSORSHIP OF THE MET LIVE IN HD IS PROVIDED BY THE HD BRODCASTS ARE SUPPORTED BY Giuseppe Verdi ERNANI Opera u etiri ina Libreto: Francesco Maria Piave prema drami Hernani Victora Hugoa SUBOTA, 25. VELJAČE 2012. POČETAK U 19 SATI. Praizvedba: Teatro La Fenice u Veneciji, 9. ožujka 1844. Prva hrvatska izvedba: Narodno zemaljsko kazalište, Zagreb, 18. studenoga 1871. Prva izvedba u Metropolitanu: 28. siječnja 1903. Premijera ove izvedbe: 18. studenoga 1983. ERNANI Marcello Giordani JAGO Jeremy Galyon DON CARLO, BUDUĆI CARLO V. Zbor i orkestar Metropolitana Dmitrij Hvorostovsky ZBOROVOĐA Donald Palumbo DON RUY GOMEZ DE SILVA DIRIGENT Marco Armiliato Ferruccio Furlanetto REDATELJ I SCENOGRAF ELVIRA Angela Meade Pier Luigi Samaritani GIOVANNA Mary Ann McCormick KOSTIMOGRAF Peter J. Hall DON RICCARDO OBLIKOVATELJ RASVJETE Gil Wechsler Adam Laurence Herskowitz SCENSKA POSTAVA Peter McClintock Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: Radnja se događa u Španjolskoj 1519. godine. Stanka nakon prvoga i drugoga čina. Svršetak oko 22 sata i 50 minuta. Tekst: talijanski. Titlovi: engleski. Foto: Metropolitan opera Metropolitan Foto: PRVI IN - IL BANDITO (“Mercè, diletti amici… Come rugiada al ODMETNIK cespite… Oh tu che l’ alma adora”). Otac Don Carlosa, u operi Don Carla, Druga slika dogaa se u Elvirinim odajama u budueg Carla V., Filip Lijepi, dao je Silvinu dvorcu. Užasnuta moguim brakom smaknuti vojvodu od Segovije, oduzevši sa Silvom, Elvira eka voljenog Ernanija da mu imovinu i prognavši obitelj. -

Pacini, Parody and Il Pirata Alexander Weatherson

“Nell’orror di mie sciagure” Pacini, parody and Il pirata Alexander Weatherson Rivalry takes many often-disconcerting forms. In the closed and highly competitive world of the cartellone it could be bitter, occasionally desperate. Only in the hands of an inveterate tease could it be amusing. Or tragi-comic, which might in fact be a better description. That there was a huge gulf socially between Vincenzo Bellini and Giovanni Pacini is not in any doubt, the latter - in the wake of his highly publicised liaison with Pauline Bonaparte, sister of Napoleon - enjoyed the kind of notoriety that nowadays would earn him the constant attention of the media, he was a high-profile figure and positively reveled in this status. Musically too there was a gulf. On the stage since his sixteenth year he was also an exceptionally experienced composer who had enjoyed collaboration with, and the confidence of, Rossini. No further professional accolade would have been necessary during the early decades of the nineteenth century On 20 November 1826 - his account in his memoirs Le mie memorie artistiche1 is typically convoluted - Giovanni Pacini was escorted around the Conservatorio di S. Pietro a Majella of Naples by Niccolò Zingarelli the day after the resounding success of his Niobe, itself on the anniversary of the prima of his even more triumphant L’ultimo giorno di Pompei, both at the Real Teatro S.Carlo. In the Refettorio degli alunni he encountered Bellini for what seems to have been the first time2 among a crowd of other students who threw bottles and plates in the air in his honour.3 That the meeting between the concittadini did not go well, this enthusiasm notwithstanding, can be taken for granted. -

A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2016 The Versatile Singer: A Guide to Vibrato & Straight Tone Danya Katok The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1394 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by DANYA KATOK A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2016 ©2016 Danya Katok All rights reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date L. Poundie Burstein Chair of the Examining Committee Date Norman Carey Executive Officer Philip Ewell, advisor Loralee Songer, first reader Stephanie Jensen-Moulton L. Poundie Burstein Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract THE VERSATILE SINGER: A GUIDE TO VIBRATO & STRAIGHT TONE by Danya Katok Advisor: Philip Ewell Straight tone is a valuable tool that can be used by singers of any style to both improve technical ideals, such as resonance and focus, and provide a starting point for transforming the voice to meet the stylistic demands of any genre. -

Donizetti Society Newsletter 10

14 The Stuarts and their kith and kin Alexander Weatherson Elis No- Figlia impura della Guisa, parli tu di disonore? Meretfice indegna oscena in te cada il mio rcssore. Profanato i il suolo Scozzese. vil puttana dal tuo piA. The other side oflhe coin? Not before dme I dare sav, and anvwav Queen Elizabeth has soi it dgh1, Scotland's soil was about 1o be Profaned by a stream ofoperas that bore the footprint ofher rival Wletherhistory should, or should not, be called brn* is a matter ofopinion but ought nor be left in the hands ofa cabal ofcerman melodramatic queens - withoul Mary Sruan Scotland miSht have been l€ii in peace. yil bellarda'l a species of Sruaft indusiry rvas a rcsult of her inlervention, in ltaly alone in the earliest decades ofthe nineieenth century there was a Scotch broth of operas by Aspa, Capecelalro, Carafa, Csrlini, Casalini, Casella, Coccia. Donizeui,-Gabrieili, Mazzucato, Mercadanter, Nicolini, Pacini, Pavesi, Pugni, Rajentroph, the Riccis, Rossini, Sogner and Vaocai - and this isjust a scraich upon the su ace ofthe European infatuation with the decapitated Stuar! and/or her nodern fastness which boiled-up in rhe bloodbath finale of the eight€€nth century, op€ras often rabid and inconsequential, full offashionable confrontations and artificial conflicts, politically molivatd, repetitious and soon forgotten At the heart ofthe plot, however, lay an ltalian, th€ puh plays and novels of Carniuo Federici (1749-1802) a former acror whose prolific vulgarisations of Schiller and Kotzebue sel ltalian librellisls scribbling for four decades Indeed, without ,ifl it is to bc suspected ihat Sir walter Scolt would never have captured the imaginaiion ofso many poets, nor for so long. -

Descendants of Mayer Amschel Rothschild

Descendants of Hirsch (Hertz) ROTHSCHILD 1 Hirsch (Hertz) ROTHSCHILD d: 1685 . 2 Callmann ROTHSCHILD d: 1707 ....... +Gütle HÖCHST m: 1658 .... 3 Moses Callman BAUER ....... 4 Amschel Moses ROTHSCHILD ............. +Schönche LECHNICH m: 1755 .......... 5 Mayer Amschel ROTHSCHILD b: 23 February 1743/44 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 19 September 1812 in Frankfurt am Main Germany ................ +Guetele SCHNAPPER b: 23 August 1753 m: 29 August 1770 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 7 May 1849 Father: Mr. Wolf Salomon SCHNAPPER .............. 6 [4] James DE ROTHSCHILD b: 15 May 1792 in Frankfurt am Main Germany d: 15 November 1868 in Paris France .................... +[3] Betty ROTHSCHILD Mother: Ms. Caroline STERN Father: Mr. Salomon ROTHSCHILD ................. 7 [5] Gustave DE ROTHSCHILD b: 1829 d: 1911 .................... 8 [6] Robert Philipe DE ROTHSCHILD b: 19 January 1880 in Paris France d: 23 December 1946 .......................... +[7] Nelly BEER b: 28 September 1886 d: 8 January 1945 Mother: Ms. ? WARSCHAWSKI Father: Mr. Edmond Raphael BEER ....................... 9 [8] Alain James Gustave DE ROTHSCHILD b: 7 January 1910 in Paris France d: 1982 in Paris France ............................. +[9] Mary CHAUVIN DU TREUI ........................... 10 [10] Robert DE ROTHSCHILD b: 1947 .............................. 11 [11] Diane DE ROTHSCHILD .................................... +[12] Anatole MUHLSTEIN d: Abt. 1959 Occupation: Diplomat of Polish Government ................................. 12 [1] Anka MULHSTEIN ...................................... -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento As an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 a Disserta

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, Ca. 1840-1940 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 © Copyright by Desiree Janene Balfour 2020 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reexamining Portamento as an Expressive Resource in Choral Music, ca. 1840-1940 by Desiree Janene Balfour Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2020 Professor William A. Kinderman, Co-Chair Professor James K. Bass, Co-Chair This study reexamines portamento as an important expressive resource in nineteenth and twentieth-century Western classical choral music. For more than a half-century, portamento use has been in serious decline and its absence in choral performance is arguably an impoverishment. The issue is encapsulated by John Potter, who writes, “A significant part of the early music agenda was to strip away the vulgarity, excess, and perceived incompetence associated with bizarre vocal quirks such as portamento and vibrato. It did not occur to anyone that this might involve the rejection of a living tradition and that singers might be in denial about their own vocal past.”1 The present thesis aims to show that portamento—despite its fall from fashion—is much more than a “bizarre vocal quirk.” When blended with aspects of the modern aesthetic, 1 John Potter, "Beggar at the Door: The Rise and Fall of Portamento in Singing,” Music and Letters 87 (2006): 538. ii choral portamento is a valuable technique that can enhance the expressive qualities of a work. -

Nini, Bloodshed, and La Marescialla D'ancre

28 Nini, bloodshed, and La marescialla d’Ancre Alexander Weatherson (This article originally appeared in Donizetti Society Newsletter 88 (February 2003)) An odd advocate of so much operatic blood and tears, the mild Alessandro Nini was born in the calm of Fano on 1 November 1805, an extraordinary centre section of his musical life was to be given to the stage, the rest of it to the church. It would not be too disrespectful to describe his life as a kind of sandwich - between two pastoral layers was a filling consisting of some of the most bloodthirsty operas ever conceived. Maybe the excesses of one encouraged the seclusion of the other? He began his strange career with diffidence - drawn to religion his first steps were tentative, devoted attendance on the local priest then, fascinated by religious music - study with a local maestro, then belated admission to the Liceo Musicale di Bologna (1827) while holding appointments as Maestro di Cappella at churches in Montenovo and Ancona; this stint capped,somewhat surprisingly - between 1830 and 1837 - by a spell in St. Petersburg teaching singing. Only on his return to Italy in his early thirties did he begin composing in earnest. Was it Russia that introduced him to violence? His first operatic project - a student affair - had been innocuous enough, Clato, written at Bologna with an milk-and-water plot based on Ossian (some fragments remain), all the rest of his operas appeared between 1837 and 1847, with one exception. The list is as follows: Ida della Torre (poem by Beltrame) Venice 1837; La marescialla d’Ancre (Prati) Padua 1839; Christina di Svezia (Cammarano/Sacchero) Genova 1840; Margarita di Yorck [sic] (Sacchero) Venice 1841; Odalisa (Sacchero) Milano 1842; Virginia (Bancalari) Genova 1843, and Il corsaro (Sacchero) Torino 1847. -

The Italian Girl in Algiers

Opera Box Teacher’s Guide table of contents Welcome Letter . .1 Lesson Plan Unit Overview and Academic Standards . .2 Opera Box Content Checklist . .8 Reference/Tracking Guide . .9 Lesson Plans . .11 Synopsis and Musical Excerpts . .32 Flow Charts . .38 Gioachino Rossini – a biography .............................45 Catalogue of Rossini’s Operas . .47 2 0 0 7 – 2 0 0 8 S E A S O N Background Notes . .50 World Events in 1813 ....................................55 History of Opera ........................................56 History of Minnesota Opera, Repertoire . .67 GIUSEPPE VERDI SEPTEMBER 22 – 30, 2007 The Standard Repertory ...................................71 Elements of Opera .......................................72 Glossary of Opera Terms ..................................76 GIOACHINO ROSSINI Glossary of Musical Terms .................................82 NOVEMBER 10 – 18, 2007 Bibliography, Discography, Videography . .85 Word Search, Crossword Puzzle . .88 Evaluation . .91 Acknowledgements . .92 CHARLES GOUNOD JANUARY 26 –FEBRUARY 2, 2008 REINHARD KEISER MARCH 1 – 9, 2008 mnopera.org ANTONÍN DVOˇRÁK APRIL 12 – 20, 2008 FOR SEASON TICKETS, CALL 612.333.6669 The Italian Girl in Algiers Opera Box Lesson Plan Title Page with Related Academic Standards lesson title minnesota academic national standards standards: arts k–12 for music education 1 – Rossini – “I was born for opera buffa.” Music 9.1.1.3.1 8, 9 Music 9.1.1.3.2 Theater 9.1.1.4.2 Music 9.4.1.3.1 Music 9.4.1.3.2 Theater 9.4.1.4.1 Theater 9.4.1.4.2 2 – Rossini Opera Terms Music -

Adelina Patti Galt Als Eine Herausragende Opernsängerin Internationalen Ranges Des Italienischen Belcanto

Patti, Adelina gendste Interpretin des Belcanto, und wenn sie auf der Bühne oder auf dem Podium erschien, löste ihre süße, glockenhelle, glänzend geschulte Stimme das Entzücken der Zuhörer aus. Dazu kam ihre hübsche, zarte Erschei- nung, ein lebhaftes Mienenspiel und feuriges Versenken in ihren Vortrag.“ Pester Lloyd, ”Morgenblatt”, 30. September 1919, 66. Jg., Nr. 183, S. 5. Profil Adelina Patti galt als eine herausragende Opernsängerin internationalen Ranges des italienischen Belcanto. Ne- ben ihrem Gesangsstil wurde auch ihre Schauspielkunst, die von Charme und großer Natürlichkeit geprägt war, ge- rühmt. Orte und Länder Adelina Patti wurde als Kind italienischer Eltern in Mad- rid geboren. Ihre Kindheit verbrachte sie in New York. Nach ihrem Konzertdebut 1851 in dieser Stadt unter- nahm die Sopranistin Konzerttourneen durch Nordame- rika, Kuba, die Karibik, Kanada und Mexiko. Nach ihrem großen Erfolg 1861 in London trat sie in der englischen Musikmetropole regelmäßig über 40 Jahre auf. Auch auf der Pariser Opernbühne war die Sängerin kontinuierlich präsent. Weiterhin unternahm die Künstlerin regelmäßig Tourneen durch ganz Europa und sang in Städten wie Wien, Berlin, Hamburg, Dresden, Wiesbaden, Amster- Adelina Patti, Hüftbild von Ch. Reutlinger dam, Brüssel, Florenz, Nizza, Rom, Neapel, Madrid, Liss- abon, Petersburg und Moskau. Mehrere Konzertreisen führten Adelina Patti wiederholt nach Nord -, Mittel- Adelina Patti und Südamerika. 1878 kaufte die Sängerin in Wales das Ehename: Adelina Adela Cederström Schloss „Craig-y-Nos“ wo sie die Zeit zwischen den Varianten: Adelina de Cuax, Adelina Nicolini, Adelina Tourneen verbrachte. Auf diesem Schloss veranstaltete Cederström, Adelina Patti-Nicolini, Adelina Adela Juana die Künstlerin regelmäßig Konzertabende. Maria Patti, Adelina Adela Juana Maria de Cuax, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Nicolini, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Biografie Cederström, Adelina Adela Juana Maria Patti-Nicolini Adelina Patti stammte aus einer Musikerfamilie. -

Kenneth E. Querns Langley Doctor of Philosophy

Reconstructing the Tenor ‘Pharyngeal Voice’: a Historical and Practical Investigation Kenneth E. Querns Langley Submitted in partial fulfilment of Doctor of Philosophy in Music 31 October 2019 Page | ii Abstract One of the defining moments of operatic history occurred in April 1837 when upon returning to Paris from study in Italy, Gilbert Duprez (1806–1896) performed the first ‘do di petto’, or high c′′ ‘from the chest’, in Rossini’s Guillaume Tell. However, according to the great pedagogue Manuel Garcia (jr.) (1805–1906) tenors like Giovanni Battista Rubini (1794–1854) and Garcia’s own father, tenor Manuel Garcia (sr.) (1775–1832), had been singing the ‘do di petto’ for some time. A great deal of research has already been done to quantify this great ‘moment’, but I wanted to see if it is possible to define the vocal qualities of the tenor voices other than Duprez’, and to see if perhaps there is a general misunderstanding of their vocal qualities. That investigation led me to the ‘pharyngeal voice’ concept, what the Italians call falsettone. I then wondered if I could not only discover the techniques which allowed them to have such wide ranges, fioritura, pianissimi, superb legato, and what seemed like a ‘do di petto’, but also to reconstruct what amounts to a ‘lost technique’. To accomplish this, I bring my lifelong training as a bel canto tenor and eighteen years of experience as a classical singing teacher to bear in a partially autoethnographic study in which I analyse the most important vocal treatises from Pier Francesco Tosi’s (c. -

I Puritani a Londra: Rassegna Stampa (Maggio - Ottobre 1835) Alice Bellini - Daniela Macchione*

i, 2015 issn 2283-8716 I Puritani a Londra: rassegna stampa (maggio - ottobre 1835) Alice Bellini - Daniela Macchione* Si pubblica qui di seguito una raccolta di recensioni relative alla prima stagione dei Puritani1 di Vincenzo Bellini al King’s Theatre di Londra (21 maggio-15 agosto 1835). Le fonti utilizzate comprendono un’ampia varietà di periodici, senza tuttavia alcuna pretesa di completezza. I due omaggi alla memoria di Bellini aggiunti alla fine della rassegna, espressione di due differenti correnti critiche, sono stati scelti tra i vari articoli pubblicati a Londra alla notizia della morte del compositore; essi riassumono i primi sei anni di presenza belliniana sulle scene inglesi e illustrano la controversa recezione critica dell’opera italiana a Londra. I documenti sono presentati in ordine alfabetico per testata e cronologico per data di pubblicazione. L’ordine cronologico qui adottato ha il vantaggio di mettere in evidenza la particolarità delle somiglianze tra articoli pubblicati in diverse testate, dovute plausibilmente soprattutto all’autoimprestito, una pratica comune nella pubblicistica musicale londinese del tempo, così spiegata da Leanne Langley: Music journalists were obliged to be neither thorough nor objective; literary recycling and self-borrowing (often without acknowledgment) were common practices; most London music journalists, then as now, were freelancers working for more than one periodical, often anonymously and perhaps shading the tone and content of their writing to suit a given journal’s market profile; -

Gianni Di Calais

GAETANO DONIZETTI GIANNI DI CALAIS Melodramma semiserio in tre atti Prima rappresentazione: Napoli, Teatro del Fondo, 2 VIII 1828 Il 1828 fu un anno felice per Gaetano Donizetti: la collaborazione con Domenico Gilardoni procedeva proficuamente e L'esule di Roma gli aveva procurato il maggior successo della sua carriera napoletana. Con Barbaja aveva sottoscritto un nuovo contratto più redditizio e meno oneroso ed il debutto genovese di Alina, regina di Golconda (12 maggio) aveva ottenuto un "felicissimo esito" (a Mayr, 15 maggio 1828). Ma soprattutto il compositore aveva potuto sposare, il primo giugno, l'amata Virginia Vasselli. Gianni di Calais, composto in quell'estate, sembra risentire di un clima particolarmente sereno e propizio. In un tono allegro e favolistico, la vicenda si svolge secondo avvenimenti regolarmente anticipati dai protagonisti, togliendo attesa ed imprevedibilità alla successione dei fatti. Tra i protagonisti spicca la figura di Rustano, paladino del migliore sentimento di amicizia. La sua parte fu scritta per il celebre buffo Antonio Tamburini, acclamato per le sue eccezionali doti di vocalista. L'esordio ("Una barchetta in mar solcando va") è una divertente barcarola: l'amenità e l'arguzia del personaggio si svelano per mezzo di una canzone popolare napoletana, che suscitò l'entusiasmo del pubblico partenopeo. È affidata a Rustano anche la lieta conclusione ("Non vi è bene senza pene"), un rondò fedele alle consuetudini del tempo. Altro interprete di rango il tenore Giovanni Battista Rubini, nel ruolo di Gianni, la cui aria d'esordio ("Feste, pompe, omaggi, onori") verrà utilizzata da Donizetti nella versione italiana della Fille du reggiment (aria di Tonio).