Melvin Edwards Painted Sculpture Alexander Gray Associates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reminiscing with James Jarvaise

REMINISCING WITH JAMES JARVAISE By Gerald Nordland The admiration I have nurtured for the work of James Jarvaise has grown from the time when, as a young art critic in Los Angeles for Frontier Magazine, I began to be aware of the burgeoning interest in the local art world for his work. It was the early fifties and I was writing about the American art world. By the mid-1950s, I was seeing more of Jarvaise’s work and wrote enthusiastically about it in Frontier, Arts, and the Los Angeles Mirror News. I was invited by Felix Landau Gallery to write an introduction for one of the shows he organized for him. The Gallery often included Jarvaise in its occasional group shows that I followed. I was well aware that Jarvaise’s work was being seen in important annual juried shows at national museums, notably: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; twice at the University of Illinois-Champaign/ Urbana (1953, 1957); Addison Gallery, Andover, MA; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH; Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.; Denver Art Museum; San Francisco Museum of Art. Notably, he received purchase awards from Addison Gallery; the then Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; the then Carnegie-Tech, Philadelphia; and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In 1958, I reported that Jarvaise had been selected by Dorothy Canning Miller, a veteran curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, NY and a valued assistant to the institution’s director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., to be among the artists featured in her Sixteen Americans exhibition. -

Frieze London

Frieze London October 2–6, 2019 Alexander Gray Associates Frieze London October 2–6, 2019 Booth G22 Alexander Gray Associates Represented Artists: Polly Apfelbaum Frank Bowling Ricardo Brey Teresa Burga Luis Camnitzer Melvin Edwards Coco Fusco Harmony Hammond Lorraine O’Grady Betty Parsons Joan Semmel Hassan Sharif Regina Silveira Valeska Soares Hugh Steers Ricardo Brey, La palabra (The word), 2018, mixed media, 19.7h x 4.72w x 26d in (50h x 12w x 66d cm) Frank Bowling Frank Bowling OBE, RA (b. 1934) was born in British Guiana and maintains studios in London and New York. For over fve decades, his distinct painting practice has been defned by an integration of autobiography and postcolonial geopolitics into abstraction. Bowling moved to London in 1953, where he studied painting at the Royal College of Art from 1959–62. Emerging at the height of the British Pop movement, his early practice emphasized the fgure while experimenting with expressive gestural applications of oil paint. In 1966, he moved to New York to immerse himself in Post-War American Art, and his practice shifted towards abstraction. It was in this environment that he became a unifying force for his peers— he curated the seminal 1969 exhibition 5+1, which featured work by Melvin Edwards, Al Loving, Jack Whitten, William T. Williams, Daniel LaRue Johnson, and himself. Concurrent with his move towards abstraction, Bowling sought inventive ways in which to continue incorporating pictorial imagery into his work. In 1964, the artist began screen-printing personal photographs onto canvas, notably a 1953 image of his mother’s general store in Guiana, Bowling’s Variety Store. -

The National Orange Show Events Calendar 689 South “E” Street • San Bernardino, CA 92408 (909) 888-6788 • (909) 889-7666 Fax

The National Orange Show Events Calendar 689 South “E” Street • San Bernardino, CA 92408 (909) 888-6788 • (909) 889-7666 Fax 15431 NOS Cover_r1.indd 4 5/21/19 1:06 PM 15431 NOS Cover_r1.indd 1 5/21/19 1:06 PM ABOUT THE COLLECTION Following a very successful art show sponsored by the San Bernardino Art Association in 1948, the National Orange Show Board of Directors decided to follow success by starting the All-California Juried Art Exhibition in 1949. Local artists responded with great enthusiasm and in ensuing years the competition to win at the Orange Show became intense and prestigious. In 1969 Karl Benjamin, an emerging artist and now internationally recognized, said ³7he Orange Show was the ¿rst exhibition I was in, so it has a special meaning to me. In 1960, there were few galleries in the Los Angeles area. There were four juried shows: the Los Angeles County Museum, Pasadena Museum, Orange Show, and Newport Harbor – and everyone sent paintings to them – getting accepted to those shows led to being accepted by the galleries.” Robert Wood was another early contributor and grew in stature in ensuing years. Francis de Erdely was well known in Europe when he came to the University of Southern California in 1945. In 1950, he entered his “Card Game,” which became part of the NOS permanent collection. John Edward Svenson, a sculptor well known for his many architectural sculptures, Ernest F. Garcia was also an early contributor with his 195 “Condor.” Fifty-¿ve years later he sculpted a second condor which was presented by the NOS to Jack Brown, CEO of Stater Bros. -

1941 Painting Today and Yesterday in the US (June 5-September 1)

1941 Painting Today and Yesterday in the U.S. (June 5-September 1) “Painting Today and Yesterday in the United States” was the museum’s opening exhibition, highlighting trends in American art from colonial times onward as it reflected the unique culture and history of the United States. The exhibition also exemplified the mission of the SBMA to be a center for the promotion of art in the community as well as a true museum (Exhibition Catalogue, 13). The exhibition included nearly 140 pieces by an array of artists, such as Walt Kuhn [1877–1949], Yasuo Kuniyoshi [1889-1953], Charles Burchfield [1893-1967], Edward Hopper [1882-1967] and Winslow Homer [1836-1910]. A very positive review of the exhibition appeared in the June issue of Art News, with particular accolades going to the folk art section. The Santa Barbara News- Press wrote up the opening in the June 1 edition, and Director Donald Bear wrote a series of articles for the News-Press that elaborated on the themes, content, and broader significance of the exhibition. Three paintings from this exhibition became part of the permanent collection of the SBMA: Henry Mattson’s [1873-1953] “Night Mystery,” Katherine Schmidt’s [early 20th century] “Pear in Paper Bag” and Max Weber’s [1881-1961] “Winter Twilight” (scrapbook 1941-1944-10). The theme of this exhibition was suggested by Mrs. Spreckels (Emily Hall Spreckels [Tremaine]) at a Board meeting and was unanimously approved. The title of the exhibition was suggested by Donald Bear, also unanimously approved by the Board. Van Gogh Paintings (& Jongkind) (September 9) Seventeen of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings were shown in this exhibition of the “most tragic painter in history.” This exhibition was shown in conjunction with the Master Impressionists show (see “Three Master French Impressionists” below). -

Melvin Edwards Melvin Edwards

Melvin Edwards Melvin Edwards October 30–December 13, 2014 Alexander Gray Associates The use of African words as titles of my sculpture extends the practical and philosophical values of the large quantity of esthetic possibility in art for now and the future. I was born in the United States, but this identity always felt compatible with African life. Naturally, I didn’t know as much until I started traveling to Africa. But my interest in what was happening there was present throughout my life. I don’t see my life in the United States and in Africa as separate. Together, they have always served a purpose. That purpose is, of course, the mixture of how I think about art. I am trying to develop something new out of old ideas and experiences. I like the idea of it being personal. Objectivity comes after I decide on the subject, it’s a way of logic. There is what is, and then there’s the objectivity you apply to it; the subject is the predecessor. Discovering and re-discovering Africa, in the sense of family, in the sense of societies. It’s all part of the modern world. Since I’ve been an adult, you can get on the telephone and you can call someone in Africa, whereas for 500 years and all the rest of human history you couldn’t do that. Now there’s a logic to anybody being connected everywhere, and this is the particular experience that informs me and connects me to Cuba, Senegal, Zimbabwe, Nigeria, and any number of other places. -

A Finding Aid to the Little Gallery Records, 1918-1985, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Little Gallery records, 1918-1985, in the Archives of American Art Christopher DeMairo The processing of this collection received Federal support from the Smithsonian Collections Care and Preservation Fund, administered by the National Collections Program and the Smithsonian Collections Advisory Committee. 2021 May 3 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 4 Series 1: Artist Files, 1941-1982.............................................................................. 4 Series 2: Exhibition Files, 1956-1975..................................................................... -

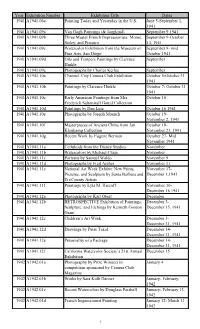

Year Exhibition Number Exhibition Title Dates 1941 A1941.06A Painting Today and Yesterday in the U.S

Year Exhibition Number Exhibition Title Dates 1941 A1941.06a Painting Today and Yesterday in the U.S. June 5-September 1, 1941 1941 A1941.09a Van Gogh Paintings (& Jongkind) September 9 1941 1941 A1941.09b Three Master French Impressionists: Monet, September 9-October Sisley, and Pissarro 14, 1941 1941 A1941.09c Watercolor Exhibition from the Museum of September 9- mid Fine Arts, San Diego October 1941 1941 A1941.09d Oils and Tempers Paintings by Clarence September Hinkle 1941 A1941.09e Photographs by Charles Kerlee September 1941 A1941.10a Channel City Camera Club Exhibition October 5-October 31 1941 1941 A1941.10b Paintings by Clarence Hinkle October 7- October 31 1941 1941 A1941.10c Early American Paintings from Mrs. October 16 Frederick Saltonstall Gould Collection 1941 A1941.10d Paintings by Dan Lutz October 16 1941 1941 A1941.10e Photographs by Joseph Muench October 19- November 2, 1941 1941 A1941.10f Masterpieces of Ancient China from Jan October 19- Kleijkamp Collection November 23, 1941 1941 A1941.10g Recent Work by Eugene Berman October 27- Mid November 1941 1941 A1941.11a Celluloids from the Disney Studios November 1941 A1941.11b Watercolors by Michael Czaja November 1941 A1941.11c Portraits by Samuel Waldo November 9 1941 A1941.11d Photographs by Fred Archer November 11 1941 A1941.11e National Art Week Exhibit: New Prints, November 17- Pictures, and Sculpture by Santa Barbara and December 1,1941 Tri-County Artists 1941 A1941.11f Paintings by Lyla M. Harcoff November 30- December 16 1941 1941 A1941.12a Photographs by Karl Obert -

Melvin Edwards by Michael Brenson

November 24, 2014 Melvin Edwards by Michael Brenson BOMB’s Oral History Project documents the life stories of New York City’s African American artists. [ Download as a PDF, EPUB, or MOBI file ] Portraits of the sculptor, Melvin Edwards, October 1965. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA Michael Brenson Your life has been an epic one, so I don’t know how we’re going to tell the story. But we have to start somewhere, so let’s go back to the beginning. You were born in the Fifth Ward, in Houston, in 1937. It was a very particular place, at a very particular time. What was it like, growing up there? Melvin Edwards Well, I’m the oldest child, and the house we lived in was my grandmother Coco’s house. She was my father’s mother; her name was Cora Ann Nickerson. She and my grandfather [James Benjamin Edwards] divorced in 1920, maybe earlier. She came to Houston, and he went to Kansas City. He would come occasionally and visit Texas, but I didn’t get to know him very well. Now, my mother’s father [James Frank Felton] lived just outside of Houston, in McNair. It was a village, part of the larger area called Goose Creek; so we saw him maybe once a month. In my teens, he came to church on Sundays in Houston and sometimes visited with us or other family members. I should explain, my father’s family’s primarily from the woods in East Texas, a place called Dotson, which is a part of a larger village called Long Branch, which is in the triangle of Nacogdoches, Henderson, and Carthage in Texas. -

The Baltimore Museum of Art Presents Melvin Edwards: Crossroads

THE BALTIMORE MUSEUM OF ART PRESENTS MELVIN EDWARDS: CROSSROADS Africa is with me every day. It’s part of my universe, along with everything else that’s part of my universe. The problem with most discussions of modernism is that they aren’t personal enough. —Melvin Edwards, 2019 BALTIMORE, MD (August 15, 2019)—The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) today announced the presentation of Melvin Edwards: Crossroads, an exhibition that explores the cross-cultural connections in the artist’s work from 1977 to the present. On view September 29, 2019 through January 12, 2020, this exhibition of 23 sculptures and installations focuses on the ways in which Edward’s dynamic welded steel works have been equally influenced by his singular vision of abstraction and by his personal experiences—from growing up during the civil rights era in the U.S. to engaging with a variety of African cultures. “Mel Edwards is a master of modern sculpture whose cosmopolitan vision of art and life reflects his engagement with the history of race, labor, and violence, as well as with themes of African Diaspora,” said Christopher Bedford, BMA Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director. “Edwards shows us a universe in which African and modern belong to a shared history of materiality and culture.” Edwards (American, b. 1937) was profoundly energized by his experience at a major arts festival in Lagos in 1977, and since then, his work has increasingly connected to African art, languages, poetry, liberation politics, and philosophy. He has made reciprocal ties to many African countries, such as Nigeria, Ghana, Zimbabwe, and Senegal, where he has maintained a home for nearly 20 years. -

Painting and Sculpture in California, the Modern Era : [Exhibition] San Francisco Museum of Modern Art September 3-November

—— — Painting and sculpture in California, th f N6530.C2 S26 15666 NEW COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA (SF) Louise Sloss Ackerman N San Francisco Museum 6530 of Modern Art C2 Painting and sculpture S26 in California, the modern era #9134 DATE DUE BORROWERS NAmT N #9134 6530 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art* C2 Painting an<l sculpture in California f S26 the modern era : [exhibition] San Francisco Museum of Modern Art September 3-November 21t 1976 ; National Collection of Fine Arts* Smithsonian Institutiont Washingtont D.C.t May 20-Septefflber 11, 1977. San Francisco : The Museum, cl977* 272 p. z ill. (some col.) ; 28 x 22 cm. Bibliography: p. 248-268. iK9134 Gift $ • • 1. Painting, American—Exhibitions. 2. Painting, Modern—20th century California—Exhibitions. 3. Sculpture, American—Exhibitions. 4. Sculpture, Modern 20th century California Exhibitions. 5. Artists California Biography. I. National Collection of Fine Arts (U.S.) II. Title i^ 31 JAN 91 3370173 NEWlxc 76-15734 DATE DUE THE LIBRARY NEW COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA 50 FELL STREET 94102 SAN FRANOSCO, CALIFORNIA (415) 626-4212 Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era San Francisco Museum of Modern Art September 3-November 21, 1976 National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. May 20-September 11, 1977 \ a) This exhibition and its catalog were supported by grants from the Foremost-McKesson Foundation, Inc., the Crown Zellerbach Foundation, Mason Wells and Frank Hamilton and the National Endowment for the Arts, Washington, D.C., a Federal agency. (P Copyright 1977 San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-15734 Table of Contents Page Acknowledgments 6 Lenders to the Exhibition 9 Preface 13 Painting and Sculpture in California: The Modern Era 19 A European's View of California Art 43 Institutions 58 Schools 69 Collecting 76 Checklist of the Exhibition 1 Modern Dawn in California: The Bay Area 82 2 The Oakland Six and Clayton S. -

James Jarvaise (1924 - 2015)

JAMES JARVAISE (1924 - 2015) Jarvaise was born in New York City, but later lived in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and eventually moved to Los Angeles in 1946. He was educated at Carnegie Tech. in Pittsburgh, PA.. Ecole Dart/ Biarritz, France with Fernand Léger, and earned a B.F.A from the University of Southern California in 1952, studied at Yale in 1953 and earned an M.F.A. in 1954 from the University of Southern California. Jarvaise relocated to Santa Barbara in 1969 and from 1991 forward served as Head of the Department of Fine and Performing Arts at Oxnard College. Museum of Modern Art curator Dorothy Canning Miller selected James Jarvaise for inclusion in the 1959 Sixteen Americans exhibition. The caliber of his work (he was selected in the class of Jay deFeo, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, and Frank Stella) was and is unquestionable. This exhibition had the potential to propel his career to great heights. However, while Jarvaise's phenomenal gifts were showcased on the West Coast, a teaching job, a growing family, and a desire for a less urban lifestyle rearranged Jarvaise's priorities. Despite obvious talent and a promising beginning, Jarvaise did not become a household name. This however, did not deter him from continuing with his art. In 2012, Louis Stern Fine Arts set out to remedy Jarvaise' obscurity with their "James Jarvaise And The Hudson River Series" exhibition. His most recent exhibition, "James Jarvaise: Collages Redux" at Louis Stern Fine Arts featured a selection of his latest work from 1989-2013. The show earned him a positive review on KCRW ArtTalk by Hunter Drohojowska-Philp.