Melvin Edwards Melvin Edwards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cbr Africa Conference Host Day Tour Program

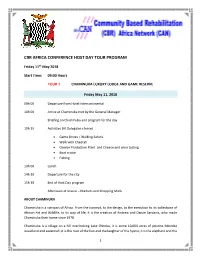

CBR AFRICA CONFERENCE HOST DAY TOUR PROGRAM Friday 11th May 2018 Start Time: 09:00 Hours TOUR 1 CHAMINUKA LUXURY LODGE AND GAME RESERVE Friday May 11, 2018 09h 00 Departure from Hotel Intercontinental 10h 00 Arrive at Chaminuka met by the General Manager Briefing on Chaminuka and program for the day 10h 15 Activities (At Delegates choice) • Game Drives / Walking Safaris • Walk with Cheetah • Cheese Production Plant and Cheese and wine tasting • Boat cruise • Fishing 13h 00 Lunch 14h 30 Departure for the city 15h 30 End of Host Day program Afternoon at leisure – Markets and Shopping Malls ABOUT CHAMINUKA Chaminuka is a synopsis of Africa. From the concept, to the design, to the execution to its collections of African Art and Wildlife, to its way of life, it is the creation of Andrew and Danae Sardanis, who made Chaminuka their home since 1978. Chaminuka is a village on a hill overlooking Lake Chitoka; it is some 10,000 acres of pristine Miombo woodland and savannah; it is the roar of the lion and the laughter of the hyena; it is the elephant and the 1 giraffe and the zebra and the eland and the sable and all the other animals of the Zambian bush; and it is the fish eagle and the kingfisher and the ibis and the egrets and the storks and the ducks and the geese and the other migratory birds that visit its lakes for rest and recuperation during their long annual sojourns from the Antarctic to the Russian steppes and back. And it is the huge private collection of contemporary African paintings and sculpture as well as traditional artefacts - more than one thousand pieces - acquired from all over Africa over a period of 50 years. -

It's Not Enough to Say 'Black Ls Beautiful' I

I : t .: t I t I I I : I 1. : By F,ank Bowling It's Not Enough to Say 'Black ls Beautiful' I I I I 1 I I I 1 AIvin Loving: Diana: Tine iip,2, 197'1.20 feet.8 inches wide: Ziede( galle(y. The probleils oi how to iudge black ari by black artists are nol made not with the works themselves or their deiivery. Not with a positrvely easier by simply installing it; herE a painler examines the works arriculared object or set of objects. It is as though what is being said is of Williams, Loving, Edwerds, Johnson and Whitten as both esthetic that whatever-black people do in the varloLLs areas labeied art ls obiecls and as symbols etpressing a unique heritago and stale of mif,d Art-hence Black Art. And various spoKesmen nake ruies to govern this supposed new form oi erpressron. Unless we accept the absurdi- ty ol such stereolypes as "they 1'e all got rhythm---." and even if we Recent New York arl has brought about curious and oiten be.rilder- do, can we stretch a little fuilher to Jay they've all got paintrng'i ing confronrations which tend to stress the potitical over the esthetic. Whichever way this question is atrswered there are orhers oi more A considerubie amount oi wnting, geared away irom hlstory, iaste immediale importance, such as: Whal precisely is lile nature ol biack and questiotrs oI quality in traditiotral esihetic terms, dnfts tcwards art'i If we reply, however, tongue-in-cheek. -

Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms

ABSTRACT ART AND THE CONTESTED GROUND OF AFRICAN MODERNISMS By PATRICK MUMBA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER of FINE ART of RHODES UNIVERSITY November 2015 Supervisor: Tanya Poole Co-Supervisor: Prof. Ruth Simbao ABSTRACT This submission for a Masters of Fine Art consists of a thesis titled Abstract Art and the Contested Ground of African Modernisms developed as a document to support the exhibition Time in Between. The exhibition addresses the fact that nothing is permanent in life, and uses abstract paintings that reveal in-between time through an engagement with the processes of ageing and decaying. Life is always a temporary situation, an idea which I develop as Time in Between, the beginning and the ending, the young and the aged, the new and the old. In my painting practice I break down these dichotomies, questioning how abstractions engage with the relative notion of time and how this links to the processes of ageing and decaying in life. I relate this ageing process to the aesthetic process of moving from representational art to semi-abstract art, and to complete abstraction, when the object or material reaches a wholly unrecognisable stage. My practice is concerned not only with the aesthetics of these paintings but also, more importantly, with translating each specific theme into the formal qualities of abstraction. In my thesis I analyse abstraction in relation to ‘African Modernisms’ and critique the notion that African abstraction is not ‘African’ but a mere copy of Western Modernism. In response to this notion, I have used a study of abstraction to interrogate notions of so-called ‘African-ness’ or ‘Zambian-ness’, whilst simultaneously challenging the Western stereotypical view of African modern art. -

Reminiscing with James Jarvaise

REMINISCING WITH JAMES JARVAISE By Gerald Nordland The admiration I have nurtured for the work of James Jarvaise has grown from the time when, as a young art critic in Los Angeles for Frontier Magazine, I began to be aware of the burgeoning interest in the local art world for his work. It was the early fifties and I was writing about the American art world. By the mid-1950s, I was seeing more of Jarvaise’s work and wrote enthusiastically about it in Frontier, Arts, and the Los Angeles Mirror News. I was invited by Felix Landau Gallery to write an introduction for one of the shows he organized for him. The Gallery often included Jarvaise in its occasional group shows that I followed. I was well aware that Jarvaise’s work was being seen in important annual juried shows at national museums, notably: Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY; twice at the University of Illinois-Champaign/ Urbana (1953, 1957); Addison Gallery, Andover, MA; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH; Corcoran Gallery, Washington D.C.; Denver Art Museum; San Francisco Museum of Art. Notably, he received purchase awards from Addison Gallery; the then Albright Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; the then Carnegie-Tech, Philadelphia; and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. In 1958, I reported that Jarvaise had been selected by Dorothy Canning Miller, a veteran curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, NY and a valued assistant to the institution’s director, Alfred H. Barr Jr., to be among the artists featured in her Sixteen Americans exhibition. -

Zambia Briefing Packet

ZAMBIA PROVIDING COMMUNITY HEALTH TO POPULATIONS MOST IN NEED se P RE-FIELD BRIEFING PACKET ZAMBIA 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ZAMBIA Country Briefing Packet Contents ABOUT THIS PACKET 3 BACKGROUND 4 EXTENDING YOUR STAY? 5 HEALTH OVERVIEW 11 OVERVIEW 14 ISSUES FACING CHILDREN IN ZAMBIA 15 Health infrastructure 15 Water supply and sanitation 16 Health status 16 NATIONAL FLAG 18 COUNTRY OVERVIEW 19 OVERVIEW 19 CLIMATE AND WEATHER 28 PEOPLE 29 GEOGRAPHy 30 RELIGION 33 POVERTY 34 CULTURE 35 SURVIVAL GUIDE 42 ETIQUETTE 42 USEFUL LOZI PHRASES 43 SAFETY 46 GOVERNMENT 47 Currency 47 CURRENT CONVERSATION RATE OF 26 MARCH, 2016 48 IMR RECOMMENDATIONS ON PERSONAL FUNDS 48 TIME IN ZAMBIA 49 EMBASSY INFORMATION 49 U.S. Embassy Lusaka 49 WEBSITES 50 !2 1151 Eagle Drive, Loveland, CO, 80537 | (970) 635-0110 | [email protected] | www.imrus.org ZAMBIA Country Briefing Packet ABOUT THIS PACKET This packet has been created to serve as a resource for the IMR Zambia Medical and Dental Team. This packet is information about the country and can be read at your leisure or on the airplane. The first section of this booklet is specific to the areas we will be working near (however, not the actual clinic locations) and contains information you may want to know before the trip. The contents herein are not for distributional purposes and are intended for the use of the team and their families. Sources of the information all come from public record and documentation. You may access any of the information and more updates directly from the World Wide Web and other public sources. -

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION

Art Seminar Group 1/29/2019 REVISION Please retain for your records WINTER • JANUARY – APRIL 2019 Tuesday, January 8, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) How A Religious Rivalry From Five Centuries Ago Can Help Us Understand Today’s Fractured World Michael Massing, author and contributor to The New York Review of Books Erasmus of Rotterdam was the leading humanist of the early 16th century; Martin Luther was a tormented friar whose religious rebellion gave rise to Protestantism. Initially allied in their efforts to reform the Catholic Church, the two had a bitter falling out over such key matters as works and faith, conduct and creed, free will and predestination. Erasmus embraced pluralism, tolerance, brotherhood, and a form of the Social Gospel rooted in the performance of Christ-like acts; Luther stressed God’s omnipotence and Christ’s divinity and saw the Bible as the Word of God, which had to be accepted and preached, even if it meant throwing the world into turmoil. Their rivalry represented a fault line in Western thinking - between the Renaissance and the Reformation; humanism and evangelicalism - that remains a powerful force in the world today. $15 door fee for guests and subscribers Tuesday, January 15, 2019 GUESTS WELCOME 1:30 pm Central Presbyterian Church (7308 York Road, Towson) Le Jazz Hot: French Art Deco Bonita Billman, instructor in Art History, Georgetown University What is Art Deco? The early 20th-century impulse to create “modern” design objects and environments suited to a fast- paced, industrialized world led to the development of countless expressions, all of which fall under the rubric of Art Deco. -

Conversations with Melvin Edwards Extended Version

s & Press Conversations with Melvin Edwards Extended Version Since the spring of 2013, I’ve talked extensively with Melvin Edwards about his life and work. A talk with Edwards moves—much like his art—with energy, force, and not infrequent bursts of humor, through a series of topics connected by associations fired from the artist’s quick-moving and wide-ranging mind. A seemingly straightforward question can prompt a spiraling string of anecdotes and observations spanning mundane commonplaces of everyday life, esoteric aesthetic concepts, and personal, familial and political history. Edwards makes sculpture through a process-oriented approach. Ordinarily, he works without sketches, although he is an inveterate and devoted maker of drawings. He begins with the spark of an idea, then continues associatively, based on what he sees, handles, remembers. The journey itself lends definition and meaning to the resulting composition, which became a good lesson to recall in conversation, whenever we ended up far from the subject we thought was our destination. Edwards and I had our conversations in various places—his studios, his apartment, his New York gallery, and the Nasher’s conference room. We also talked as we drove through Los Angeles neighborhoods, and as we sat together in restaurants and coffee shops. In sorting through our many digressions, mutual interruptions, and asides, to select the excerpts that follow, I’ve attempted to choose exchanges that provide heretofore unavailable information, especially about the first decade or so of Edwards’ career, and that reveal something of the artist’s concerns and, more elusively, his turn of mind. -

ACASA Newsletter 117, Winter 2021 Welcome from ACASA

Volume 117 | Winter 2021 ACASA Newsletter 117, Winter 2021 Welcome from ACASA From the President Dear ACASA Members, The world-wide injustices of this past year coupled with the global pandemic have affected many of our lives. This week in the United States we are celebrating Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as well as the inauguration of President-Elect Joseph Biden and Vice President-Elect Kamala Harris. It will be, in the words of another great U.S. president, “not a victory of party, but a celebration of freedom ─ symbolizing an end as well as a beginning ─ signifying renewal as well as change.” (J.F.K.’s Inaugural Address, 1961). It is this moment, ripe with potential, that we celebrate. It is not about accepting those whose actions or views we abhor, but shifting our attention to a deeper level, to, as Dr. King wrote, a "creative, redemptive goodwill for all" that has the power to bring us together by appealing to our best nature. I look forward to the coming months as we prepare to gather at our Triennial in June. The virtual format will allow us enriching experiences including interactive panels, studio, gallery, and museum walk-throughs, tributes, networking, and lively discussions that can go on long past panel completion. Our virtual conference will draw us together and inspire. In Strength and Solidarity, Peri ACASA President ACASA website From the Editor Dear ACASA Members, In my two years serving as the ACASA newsletter editor, I cannot recall receiving so many long range exhibition announcements as this time. Obviously, while museums are closed, new exhibitions never properly opened and cultural life is shut down, the energies concentrate on looking ahead. -

Mark Godfrey on Melvin Edwards and Frank Bowling in Dallas

May 1, 2015 Reciprocal Gestures: Mark Godfrey on Melvin Edwards and Frank Bowling in Dallas https://artforum.com/inprint/issue=201505&id=51557 Mark Godfrey, May 2015 View of “Frank Bowling: Map Paintings,” 2015, Dallas Museum of Art. From left: Texas Louise, 1971; Marcia H Travels, 1970. “THIS EXHIBITION is devoted to commitment,” wrote curator Robert Doty in the catalogue for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1971 survey “Contemporary Black Artists in America.” He continued, “It is devoted to concepts of self: self-awareness, self-understanding and self-pride— emerging attitudes which, defined by the idea ‘Black is beautiful,’ have profound implications in the struggle for the redress of social grievances.” In fact, the Whitney’s own commitment to presenting the work of African American artists might not have been as readily secured without the prompting of an activist organization, the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition. The BECC had been founded in 1969 to protest the exclusion of painters and sculptors from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s documentary exhibition “Harlem on My Mind,” and that same year, several of its members had requested a meeting with the Whitney’s top brass, commencing a dialogue that was to go on for months. The back-and-forth was at times frustrating for the BECC’s representatives—artist Cliff Joseph, for example, was to recall that the Whitney leadership resisted the coalition’s request that a black curator organize the group exhibition. But unlike many art institutions at that time, the museum did recognize the strength of work by contemporary African American artists—and did bring that work to the public, not only in Doty’s survey but also, beginning in 1969, in a series of groundbreaking and prescient monographic shows. -

Frieze London

Frieze London October 2–6, 2019 Alexander Gray Associates Frieze London October 2–6, 2019 Booth G22 Alexander Gray Associates Represented Artists: Polly Apfelbaum Frank Bowling Ricardo Brey Teresa Burga Luis Camnitzer Melvin Edwards Coco Fusco Harmony Hammond Lorraine O’Grady Betty Parsons Joan Semmel Hassan Sharif Regina Silveira Valeska Soares Hugh Steers Ricardo Brey, La palabra (The word), 2018, mixed media, 19.7h x 4.72w x 26d in (50h x 12w x 66d cm) Frank Bowling Frank Bowling OBE, RA (b. 1934) was born in British Guiana and maintains studios in London and New York. For over fve decades, his distinct painting practice has been defned by an integration of autobiography and postcolonial geopolitics into abstraction. Bowling moved to London in 1953, where he studied painting at the Royal College of Art from 1959–62. Emerging at the height of the British Pop movement, his early practice emphasized the fgure while experimenting with expressive gestural applications of oil paint. In 1966, he moved to New York to immerse himself in Post-War American Art, and his practice shifted towards abstraction. It was in this environment that he became a unifying force for his peers— he curated the seminal 1969 exhibition 5+1, which featured work by Melvin Edwards, Al Loving, Jack Whitten, William T. Williams, Daniel LaRue Johnson, and himself. Concurrent with his move towards abstraction, Bowling sought inventive ways in which to continue incorporating pictorial imagery into his work. In 1964, the artist began screen-printing personal photographs onto canvas, notably a 1953 image of his mother’s general store in Guiana, Bowling’s Variety Store. -

Fall 1988 CAA Newsletter

newsletter Volume 13, Number 3 Fall 1988 nominations for CAA board of directors The 1988 Nominating Committee has submitted its initial slate of nine State Building; Art Bank-Dept of State; and numerous college/uni nominees to serve on the CAA board of directors from 1989 to 1993. versity and corporate collections. AWARDS: NEA fellowship grant; The slate of candidates has been chosen with an eye to representation Louis Comfort Tiffany grant; Illinois Arts Council fellowship grant; based on region and discipline (artists, academic art historians, muse Senior Fulbright Scholar Australia. PROFESSIONAL ACTIVlTIES: NEA um professionals). The nominating committee asks that voters take juror; Mid-America Art Alliance/ NEA juror. cAA ACTIVITIES: annual such distribution into account in making their selection of candidates. meeting panelist, 1988. The current elected board of directors is composed of: eight artists There is an ongoing need to evaluate amongst ourselves the qualt~y (32%), twelve academically-affiliated art historians (48%), and five and type oj education undergraduate and graduate programs are pro museum professionals (20%). Of those, eight are men (32%) and viding. It is no longer enough to simply teach "how to. " The art world seventeen are women (68%); sixteen represent the northeast and mid continues to demand more theoretical and critical dialogue as the em Atlantic (64%), four represent the midwest (16%), two represent the phasis on content and context accelerates. Furthermore, Jewer west (8%), one represents the southeast (4%), and two represent the academic opportunities are juxtaposed with student cynicism about southwest (8%). This compares to the following breakdown of the the art world and how to "make it big out there." I see a needJorJac membership: artists 43%; academically-affiliated art historians 44%; ulty to inJuse their art programs with a renewed commitment to integ museum professionals 11 %; male 46%; female 54%; northeast/mid rity, authentic~~y, social responsibility and depth of ideas. -

A Major Melvin Edwards Retrospective Is Coming to Manhattan's City Hall

The Architect’s Newspaper A major Melvin Edwards retrospective is coming to Manhattan’s City Hall Park Matt Hickman 27 April 2021 A major Melvin Edwards retrospective is coming to Manhattan’s City Hall Park Image: Melvin Edwards, Homage to Coco, 1970; painted steel and chain. (Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York; Stephen Friedman Gallery, London; © Melvin Edwards/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York) The Public Art Fund has announced a thematic survey of Melvin “Mel” Edwards, a Houston-born artist, educator, and welder whose celebrated collective body of work touches down on themes of race, identity, and social injustice, will open at City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan on May 5. The historic exhibition, titled Melvin Edwards: Brighter Days, will run through November 28. Based in Los Angeles during the formative stages of his career, Edwards, now 83, moved to New York City in the late 1960s ahead of a pioneering 1970 exhibition in which he became the first African American sculptor to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Edwards is best known for his muscular, abstract welded steel installations, including the Lynch Fragments series, that incorporate barbed wire, chains, pipe fittings, nails, and machine parts. The first work by Edwards commissioned by the non-profit Public Art Fund was Tomorrow’s Wind in 1991, which was initially installed at Doris C. Freedman Plaza in Central Park and is now on view at Thomas Jefferson Park in East Harlem. In addition to Tomorrow’s Wind, three other works by Edwards are permanently installed across the city.