The Influence of Winds and Currents on European Maritime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i: Nā Makani

November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai‘i: Nā Makani Mau Steven Businger & Sara da Silva [email protected], [email protected] Iasona Ellinwood, [email protected] Pauline W. U. Chinn, [email protected] University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Figure 1. Schematic of global circulation Grades: 6-8, modifiable for 9-12 Time: 2 - 10 hours Nā Honua Mauli Ola, Guidelines for Educators, No Nā Kumu: Educators are able to sustain respect for the integrity of one’s own cultural knowledge and provide meaningful opportunities to make new connections among other knowledge systems (p. 37). Standard: Earth and Space Science 2.D ESS2D: Weather and Climate Weather varies day to day and seasonally; it is the condition of the atmosphere at a given place and time. Climate is the range of a region’s weather over one to many years. Both are shaped by complex interactions involving sunlight, ocean, atmosphere, latitude, altitude, ice, living things, and geography that can drive changes over multiple time scales—days, weeks, and months for weather to years, decades, centuries, and beyond for climate. The ocean absorbs and stores large amounts of energy from the sun and releases it slowly, moderating and stabilizing global climates. Sunlight heats the land more rapidly. Heat energy is redistributed through ocean currents and atmospheric circulation, winds. Greenhouse gases absorb and retain the energy radiated from land and ocean surfaces, regulating temperatures and keep Earth habitable. (A Framework for K-12 Science Education, NRC, 2012) Hawai‘i Content and Performance Standards (HCPS) III http://standardstoolkit.k12.hi.us/index.html 1 November 19, 2012 Hadley Cell and the Trade Winds of Hawai'i STRAND THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS Standard 1: The Scientific Process: SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION: Discover, invent, and investigate using the skills necessary to engage in the scientific process Benchmarks: SC.8.1.1 Determine the link(s) between evidence and the Topic: Scientific Inquiry conclusion(s) of an investigation. -

Sidon's Ancient Harbour

ARCHAEOLOGY & H ISTORY SIDON’S ANCIENT HARBOUR: IN THE LEBANON ISSUE THIRTY FOUR -T HIRTY FIVE : NATURAL CHARACTERISTICS WINTER /S PRING 2011/12. AND HAZARDS PP. 433-459. N. CARAYON 1 C. MORHANGE 2 N. MARRINER 2 1 CNRS UMR 5140, A multidisciplinary study combining geoscience, archaeology and his - Lattes ([email protected]) tory was conducted on Sidon’s harbour (Lebanon). The natural charac - teristics of the site at the time of the harbour’s foundation were deter - 2 CNRS CEREGE UMR mined, as well as the human resources that were needed to improve 6635, Aix-Marseille Université, Aix-en- these conditions in relation to changes in maritime activity. In ancient Provence times, Sidon was one of the most active harbours and urban centres on ([email protected] ; the Levantine coast 3. It is therefore a key site to study ancient harbours, [email protected]). providing insight into both ancient cultures and the technological 1 Sidon’s coastal ba- thymetry. 1 apogee of the Roman and Byzantine periods. This article proposes a synthesis of Sidon’s harbour system based on geomorphological characteristics that favoured the development of a wide range of maritime facilities, refashioned and improved by human societies from the second millennium BC until the Middle Ages. 434 2 2 Aerial view of Sidon Sidon’ s coastline (fig. 1 -2) and Ziré during the 1940s (from A. Poide- The ancient urban center was developed on a rocky promontory dom - bard and J. Lauffray, inating a 2 km wide coastal plain, flanked by the Nahr el-Awali river to 1951). -

Surface Currents Near the Greater and Lesser Antilles

SURFACE CURRENTS NEAR THE GREATER AND LESSER ANTILLES by C.P. DUNCAN rl, S.G. SCHLADOW1'1 and W.G. WILLIAMS SUMMARY The surface flow around the Greater and Lesser Antilles is shown to differ considerably from the widely accepted current system composed of the Caribbean Current and Antilles Current. The most prominent features deduced from dynamic topography are a flow from the north into the Caribbean near Puerto Rico and a permanent eastward-flowing counter-current in the Caribbean itself between Puerto Rico and Venezuela. Noticeably absent is the Antilles Current. A satellite-tracked buoy substantiates the slow southward flow into the Caribbean and the absence of the Antilles Current. INTRODUCTION Pilot Charts for the North Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea (Defense Mapping Agency, 1968) show westerly surface currents to the North and South of Puerto Rico. The Caribbean Current is presented as an uninterrupted flow which passes through the Caribbean Sea, Yucatan Straits, Gulf of Mexico, and Florida Straits to become the Gulf Stream. It is joined off the east coast of Florida by the Antilles Current which is shown as flowing westwards along the north coast of Puerto Rico and then north-westerly along the northern edge of the Bahamas (BOISVERT, 1967). These surface currents are depicted as extensions of the North Equatorial Current and the Guyana Current, and as forming part of the subtropical gyre. As might be expected in the absence of a western boundary, the flow is slow-moving, shallow and broad. This interpretation of the surface currents is also presented by WUST (1964) who employs the same set of ship’s drift observations as are used in the Pilot Charts. -

Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 61 Doi: 10.3897/Subtbiol.10.4760

Subterranean Biology 10: 61-73, 2012 (2013) Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 61 doi: 10.3897/subtbiol.10.4760 Lazare Botosaneanu ‘Naturalist’ 1927 – 2012 demic training shortly after the Second World War at the Faculty of Biology of the University of Bucharest, the same city where he was born and raised. At a young age he had already showed interest in Zoology. He wrote his first publication –about a new caddisfly species– at the age of 20. As Botosaneanu himself wanted to remark, the prominent Romanian zoologist and man of culture Constantin Motaş had great influence on him. A small portrait of Motaş was one of the few objects adorning his ascetic office in the Amsterdam Museum. Later on, the geneticist and evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky and the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr greatly influenced his thinking. In 1956, he was appoint- ed as a senior researcher at the Institute of Speleology belonging to the Rumanian Academy of Sciences. Lazare Botosaneanu began his career as an entomologist, and in particular he studied Trichoptera. Until the end of his life he would remain studying this group of insects and most of his publications are dedicated to the Trichoptera and their environment. His colleague and friend Prof. Mar- cos Gonzalez, of University of Santiago de Compostella (Spain) recently described his contribution to Entomolo- gy in an obituary published in the Trichoptera newsletter2 Lazare Botosaneanu’s first contribution to the study of Subterranean Biology took place in 1954, when he co-authored with the Romanian carcinologist Adriana Damian-Georgescu a paper on animals discovered in the drinking water conduits of the city of Bucharest. -

Caribbean Current Variability and the Influence of the Amazon And

ARTICLE IN PRESS Deep-Sea Research I 54 (2007) 1451–1473 www.elsevier.com/locate/dsri Caribbean current variability and the influence of the Amazon and Orinoco freshwater plumes L.M. Che´rubina,Ã, P.L. Richardsonb aRosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, 4600 Rickenbacker Causeway, FL 33149 Miami, USA bDepartment of Physical Oceanography, MS 29, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, 360 Woods Hole Road, Woods Hole, MA 0254, USA Received 5 February 2006; received in revised form 16 April 2007; accepted 24 April 2007 Available online 18 May 2007 Abstract The variability of the Caribbean Current is studied in terms of the influence on its dynamics of the freshwater inflow from the Orinoco and Amazon rivers. Sea-surface salinity maps of the eastern Caribbean and SeaWiFS color images show that a freshwater plume from the Orinoco and Amazon Rivers extends seasonally northwestward across the Caribbean basin, from August to November, 3–4 months after the peak of the seasonal rains in northeastern South America. The plume is sustained by two main inflows from the North Brazil Current and its current rings. The southern inflow enters the Caribbean Sea south of Grenada Island and becomes the main branch of the Caribbean Current in the southern Caribbean. The northern inflow (141N) passes northward around the Grenadine Islands and St. Vincent. As North Brazil Current rings stall and decay east of the Lesser Antilles, between 141N and 181N, they release freshwater into the northern part of the eastern Caribbean Sea merging with inflow from the North Equatorial Current. Velocity vectors derived from surface drifters in the eastern Caribbean indicate three westward flowing jets: (1) the southern and fastest at 111N; (2) the center and second fastest at 141N; (3) the northern and slowest at 171N. -

Collected Contributions of Invited Lecturers and Authors to the 10C/FAO/U N EP International Workshop on Marine Pollution in the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions

.- -/ce,9e6L1 420■4 • 3/L•Ikrf: 7 Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop report no. 11 - Supplement/ IIBLIOTECik KACIONES HOS MEXICO Collected contributions of invited lecturers and authors to the 10C/FAO/U N EP International Workshop on Marine Pollution in the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, 13-17 December 1976 Unesco . Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Workshop report no.11 Supplement Collected contributions of invited lecturers and authors to the IOC/FAO/UNEP International Workshop on Marine Pollution in the Caribbean and Adjacent Regions Port-of-Spain, Trinidad & Tobago, 13-17 December 1976. UNESCO 1977 SC-78/WS/1 Paris, January 1978 Original: English CONTENTS pails 1 INTRODUCTION INFORMATION PAPERS Preliminary review of problems of marine pollution in the Caribbean and adjacent 2-28 regions. by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. A review of river discharges in the Caribbean and adjacent regions by Jean-Marie Martin 29-46 and M. Meybeck. INVITED LECTURES Regional oceanography as it relates to present and future pollution problems -79 and living resources - Caribbean. by Donald K. Atwood. 47 Regional oceanography as it relates to present and future pollution problems 80-105 and living resources - Gulf of Mexico. by Ingvar Emilsson. Pollution research and monitoring for by Enrique Mandelli. 106-145 heavy metals. Pollution research and monitoring for hydrocarbons: present status of the studies of petroleum contamination in by Alfonso Vazquez 146-158 the Gulf of Mexico. Botello. Pollution research and monitoring for halogenated hydrocarbons and by Eugene Corcoran. 159-168 pesticides. Pollutant transfer and transport in by Gunnar Kullenberg. -

Development and Implementation of Sargassum Early Advisory System (SEAS)

Development and implementation of Sargassum Early Advisory System (SEAS) By Robert K. Webster Ph.D. candidate, Marine Sciences Department [email protected] Dr. Tom Linton Professor, Marine Science Department [email protected] Texas A&M University at Galveston, P.O. Box 1675, Galveston, Texas 77553 ABSTRACT hardship, since their annual budgets have little or no room for The Texas Gulf Coast consists of 367 miles of coastline, unforeseen expenditures. To assist beach management efforts, primarily sandy beaches. The slight slope of these beaches scientists at Texas A&M University at Galveston have been creates many large expanses of beach where the public can investigating the use of satellite imagery to forecast Sargas- enjoy a variety of activities such as beach combing, surfing, sum landings along the Texas coastline. This Sargassum Early swimming, and surf fishing. Communities that manage these Advisory System (SEAS) is designed to give coastal managers areas rely heavily on tourism as a primary source of income. as much warning as possible, allowing them to adjust their Texas beach tourism generates approximately $7 billion per allocation of resources for the management of Sargassum year, according to the Texas General Land Office’s (TGLO) landings. SEAS model uses satellite imagery from Landsat website (http://www.glo.texas.gov). Public use of these beaches Data Continuity Mission (LANDSAT) satellites to track the can be severely restricted by the periodic mass landings of movement of Sargassum as it approaches each sector along the free-floating plant Sargassum, commonly referred to as the Texas Gulf Coast. During 2012, a total of 38 advisories seaweed. -

Doug Wilson C/O NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office, 410 Severn Avenue

2.4 THE NOPP YEAR OF THE OCEAN DRIFTER PROGRAM Doug Wilson NOAA/AOML, Miami, FL organize themselves until they approach the 1. INTRODUCTION Yucatan Channel, where they form into a coherent northward flow known as the Yucatan Current. Beginning in March of 1998, over 150 WOCE Once through the Yucatan Channel, the flow type drifting buoys, drogued at 15 meters depth, were launched in the Gulf of Mexico and the becomes the Loop Current in the Gulf of Mexico Caribbean Sea and their approaches, providing in and then the Florida Current east of the excess of 30,000 drifter days of data to date. southeastern U.S. coast. The manner in which Buoys were provided by the U.S. National Ocean these warm western Atlantic and Caribbean currents organize into the powerful Florida Current / Partnership Program; launch co-ordination was provided by NOAA and academic research Gulf Stream system is not well understood. scientists interested in regional ocean circulation studies; and logistical and data processing support The Caribbean Sea is also the location of some was provided by the NOAA/AOML Global Drifter of the richest coastal and reef habitats in the tropical oceans. As the Caribbean Current flows and Data Assembly Centers. Buoys were launched with the cooperation of commercial ships, the westward on its way to the Yucatan Peninsula, it Colombian Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard, and passes through very productive zones of coastal research vessels working in the region. Drifter track upwelling (produced by the easterly winds) north of figures and data have been made available in real Venezuela and Colombia, fertile coastal "nurseries" and estuaries such as the Cienaga Grande de time via the WWW at www.IASlinks.org and www.drifters.doe.gov. -

Distributional Impacts of Fisheries Subsidies and Their Reform Case Studies of Senegal and Vietnam

Distributional impacts of fisheries subsidies and their reform Case studies of Senegal and Vietnam Sarah Harper and U Rashid Sumaila Working Paper Fisheries; Sustainable markets Keywords: March 2019 Sustainable fisheries; fossil fuel subsidies; livelihoods; gender and generation; equity About the authors Sarah Harper, Fisheries Economics Research Unit, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia; U Rashid Sumaila, Fisheries Economics Research Unit, Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia Corresponding author email [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Shaping Sustainable Markets Group The Shaping Sustainable Markets group works to make sure that local and global markets are fair and can help poor people and nature to thrive. Our research focuses on the mechanisms, structures and policies that lead to sustainable and inclusive economies. Our strength is in finding locally appropriate solutions to complex global and national problems. Partner organisation The Fisheries Economics Research Unit strives for interdisciplinary solutions to global, national, and local marine and freshwater management issues. We focus on economic and policy analysis and mobilize researchers, students, and practitioners to advance resource management for the benefit of current and future generations, while maintaining ‘healthy’ ecosystems. Published by IIED, March 2019 Sarah Harper, U Rashid Sumaila (2019) Distributional impacts of fisheries subsidies and their reform: case studies of Senegal and Vietnam. -

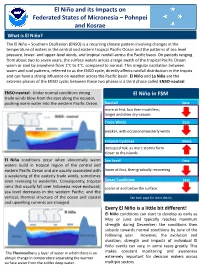

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

September2021

September 2021 Sponsored by Kraken Yachts Ocean Sailor 2 From The Pulpit Ocean Sailor 3 A Krakin Life Feature 5 One Tack Forward Two Tacks Back Ocean Sailor 11 On Watch Sailing Skills 13 Preparing for failure Birth Of A Blue Water Yacht 16 Commissioning Sofia Marie Travel & Discovery 22 Mediterranean: The Inland Sea September 2021 Sailing Skills 30 Sailing Tails: Dogs On board Technical & Equipment 38 Built for sail or sale? Travel & Discovery 42 Dropping Anchor Knot/Splice Of The Month 46 Spanish Bowline Ocean Sailor 47 Mariner’s Library In The Galley 48 Kerala Chicken & Aubergine Curry Why not share the enjoyment with a Are you loving friend? Click the button on the right and sign a friend up to Ocean Sailor magazine Click here to subscribe a friend Ocean Sailor magazine? today, it's free! Page 1 Ocean Sailor Magazine | September 2021 From The Pulpit By Dick Beaumont - Chairman and Founder of Ocean Sailor Magazine and Kraken Yachts Where to begin? It’s been one hell of a seemed impossible, even to me, but that was ludicrously low and down right misleading month. We commenced the build of the the reality. Admittedly, she had a very clean ‘category A Ocean’, amongst other next Kraken 50. We also completed the sea bottom and a fantastic set of brand new erroneous elements, only required a yacht to trials of Sofia Marie K50 003. We’ve also Vectrans radial cut sails (built by my good be built to withstand 4 metre seas and force had a phalanx of clients and media out test friend Kaan Is of Quantum Sails Turkey) but 8 winds ( 34 kts), which then allows the sailing and viewing both the K50 and White still very impressive nonetheless. -

Vocabulaires Et Toponymie Des Pays De Montagne

VOCABULAIRES et TOPONYMIE des pays de MONTAGNE Robert LUFT Club Alpin Français de Nice – Mercantour 2 Vocabulaires et toponymie des pays de montagne Avant-Propos Tels qu'ils se présentent à nos yeux, les paysages sont le résultat de l'action millénaire des forces de la nature sur le socle des terres émergées, conjuguée avec celle des interventions humaines. Les plaines et leurs abords collinaires sont caractérisés aujourd'hui par une agriculture mécanisée, par l'importance des réseaux de voies de communication, ainsi que par une urbanisation envahissante. Au cours de la seconde moitié du 20ème siècle, les paysages agricoles ouverts, traditionnellement formés de champs et de bocages microparcellaires, ont cédé la place à de vastes étendues dénudées, indispensables à la pratique des nouveaux modes de culture. Par ailleurs, beaucoup de villages et de bourgs dépérissent ou se transforment en cités-dortoirs de grandes agglomérations de plus en plus envahissantes. Pour décrire son paysage de plaine le citadin, désormais majoritaire, n'a plus recours aux termes nuancés de quelqu'un qui tire son existence des produits de la terre ; son mode d'expression est plus technique, mais aussi plus pauvre que celui du cultivateur d'antan. Dans les zones de la montagne, au contraire, l'aspect du paysage a peu évolué, malgré l'apparition de nouvelles techniques agricoles. Les formes variées du terrain imposent leur marque aux paysages dont les structures naturelles sont celles d'espaces clos, limités par des barrières rocheuses et des cours d'eau, infranchissables par endroits. Ces milieux âpres dont, il y a peu encore, il était difficile de s'échapper sans d'importants efforts physiques, limitent les échanges.