Linda Nochlin, Trailblazing Feminist Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Release

Press Release April 2015 Miss Piggy to Receive Her First Award at the 2015 Sackler Center First Awards at the Brooklyn Museum on June 4 Event to Feature Miss Piggy in Conversation with Gloria Steinem Kermit the Frog to Attend Ceremony Miss Piggy, ultimate diva and star of stage and screen, who has inspired generations throughout the world, will receive her very first award at the annual Sackler Center First Awards at the Brooklyn Museum. Kermit the Frog, who has received numerous awards and accolades in his lifetime, will be in the audience to witness this great honor. The awards ceremony and reception will take place at the Brooklyn Museum on Thursday, June 4, from 5 to 7 p.m. A private reception will be followed by the award presentation to Miss Piggy by Elizabeth Sackler. Miss Piggy, who was recently called “The Gloria Steinem of the Muppet world” by the Daily Beast, will give a brief acceptance speech, followed by a 20-minute video retrospective of her career, after which she will take the stage with Ms. Steinem, who has been on hand for the Sackler Center First Awards since its 2012 launch. The Muppets Studio will be sponsoring several groups attending this special event including children and their families from Ronald McDonald House New York, a temporary home-away-from-home for families battling pediatric cancer; Brooklyn-based Girl Scout Troops 2081 and 2158; Brooklyn-based Girls for Gender Equity; and artists from Groundswell, a community mural project. The annual Sackler Center First Awards celebrates women who have broken gender barriers and made remarkable contributions in their fields. -

“My Personal Is Not Political?” a Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 5, No. 2, July 2009 “My Personal Is Not Political?” A Dialogue on Art, Feminism and Pedagogy Irina Aristarkhova and Faith Wilding This is a dialogue between two scholars who discuss art, feminism, and pedagogy. While Irina Aristarkhova proposes “active distancing” and “strategic withdrawal of personal politics” as two performative strategies to deal with various stereotypes of women's art among students, Faith Wilding responds with an overview of art school’s curricular within a wider context of Feminist Art Movement and the radical questioning of art and pedagogy that the movement represents Using a concrete situation of teaching a women’s art class within an art school environment, this dialogue between Faith Wilding and Irina Aristakhova analyzes the challenges that such teaching represents within a wider cultural and historical context of women, art, and feminist performance pedagogy. Faith Wilding has been a prominent figure in the feminist art movement from the early 1970s, as a member of the California Arts Institute’s Feminist Art Program, Womanhouse, and in the recent decade, a member of the SubRosa, a cyberfeminist art collective. Irina Aristarkhova, is coming from a different history to this conversation: generationally, politically and theoretically, she faces her position as being an outsider to these mostly North American and, to a lesser extent, Western European developments. The authors see their on-going dialogue of different experiences and ideas within feminism(s) as an opportunity to share strategies and knowledges towards a common goal of sustaining heterogeneity in a pedagogical setting. First, this conversation focuses on the performance of feminist pedagogy in relation to women’s art. -

Women, Art, and Power After Linda Nochlin

Women, Art, and Power After Linda Nochlin Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/octo/article-pdf/doi/10.1162/OCTO_a_00320/1754182/octo_a_00320.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 MIGNON NIXON In November 2001, thirty years after Linda Nochlin wrote “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” Carol Armstrong, then director of the Program in the Study of Women and Gender at Princeton, convened a conference, “Women Artists at the Millennium,” to consider the galvanizing effects of the essay on art and art history. Armstrong emphasized that the event’s focus would be “the contemporary situation.” 1 For those two days, we would think with Nochlin about what had changed after 1971—after the essay, after the women’s liberation movement, after the emer - gence of a feminist discourse in art and art history—and about how that discourse continued to evolve as feminism, in all its critical articulations, reimagined the ques - tions art and art history might pose. “At its strongest,” Nochlin declared, “a feminist art history is a transgressive and anti-establishment practice meant to call many of the major precepts of the discipline into question.” 2 But as it turned out, those gathered in Princeton that November weekend were also compelled to think with Nochlin about what was to come after the attacks of 9/11, after the invasion of Afghanistan, and after a political regression to delusions of mastery and supremacy that threatened to undo three decades of collective work on “women, art, and power.” A shadow “hung over us so immediately that the triumphalism that seemed to hover around the notion of ‘women artists at the millennium’ was converted into its epically anxious opposite,” Armstrong recalled. -

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL

WOMAN's. ART JOURNAL (on the cover): Alice Nee I, Mary D. Garrard (1977), FALL I WINTER 2006 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 2 oil on canvas, 331/4" x 291/4". Private collection. 2 PARALLEL PERSPECTIVES By Joan Marter and Margaret Barlow PORTRAITS, ISSUES AND INSIGHTS 3 ALICE EEL A D M E By Mary D. Garrard EDITORS JOAN MARTER AND MARGARET B ARLOW 8 ALI CE N EEL'S WOMEN FROM THE 1970s: BACKLASH TO FAST FORWA RD By Pamela AHara BOOK EDITOR : UTE TELLINT 12 ALI CE N EE L AS AN ABSTRACT PAINTER FOUNDING EDITOR: ELSA HONIG FINE By Mira Schor EDITORIAL BOARD 17 REVISITING WOMANHOUSE: WELCOME TO THE (DECO STRUCTED) 0 0LLHOUSE NORMA BROUDE NANCY MOWLL MATHEWS By Temma Balducci THERESE DoLAN MARTIN ROSENBERG 24 NA CY SPERO'S M USEUM I CURSIO S: !SIS 0 THE THR ES HOLD MARY D. GARRARD PAMELA H. SIMPSON By Deborah Frizzell SALOMON GRIMBERG ROBERTA TARBELL REVIEWS ANN SUTHERLAND HARRis JUDITH ZILCZER 33 Reclaiming Female Agency: Feminist Art History after Postmodernism ELLEN G. LANDAU EDITED BY N ORMA BROUDE AND MARY D. GARRARD Reviewed by Ute L. Tellini PRODUCTION, AND DESIGN SERVICES 37 The Lost Tapestries of the City of Ladies: Christine De Pizan's O LD CITY P UBLISHING, INC. Renaissance Legacy BYS uSAN GROAG BELL Reviewed by Laura Rinaldi Dufresne Editorial Offices: Advertising and Subscriptions: Woman's Art journal Ian MeUanby 40 Intrepid Women: Victorian Artists Travel Rutgers University Old City Publishing, Inc. EDITED BY JORDANA POMEROY Reviewed by Alicia Craig Faxon Dept. of Art History, Voorhees Hall 628 North Second St. -

Beyond the Orientalist Canon: Art and Commerce

© COPYRIGHT by Fanna S. Gebreyesus 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1 BEYOND THE ORIENTALIST CANON: ART AND COMMERCE IN JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME'S THE SNAKE CHARMER BY Fanna S. Gebreyesus ABSTRACT This thesis re-examines Jean-Léon Gérôme's iconic painting The Snake Charmer (1879) in an attempt to move beyond the post-colonial interpretations that have held sway in the literature on the artist since the publication of Linda Nochlin’s influential essay “The Imaginary Orient” in 1989. The painting traditionally is understood as both a product and reflection of nineteenth-century European colonial politics, a view that positions the depicted figures as racially, ethnically and nationally “other” to the “Western” viewers who encountered the work when it was exhibited in France and the United States during the final decades of the nineteenth century. My analysis does not dispute but rather extends and complicates this approach. First, I place the work in the context of the artist's oeuvre, specifically in relation to the initiation of Gérôme’s sculptural practice in 1878. I interpret the figure of the nude snake charmer as a reference to the artist’s virtuoso abilities in both painting and sculpture. Second, I discuss the commercial success that Gérôme achieved through his popular Orientalist works. Rather than simply catering to the market for Orientalist scenes, I argue that this painting makes sophisticated commentary on its relation to that market; the performance depicted in the work functions as an allegory of the painting’s reception. Finally, I discuss the display of this painting at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, in an environment of spectacle that included the famous “Oriental” exhibits in the Midway Plaisance meant to dazzle and shock visitors. -

A Tribute to Linda Nochlin | the Brooklyn Rail

6/13/2017 A Tribute to Linda Nochlin | The Brooklyn Rail MAILINGLIST Editor's Message July 13th, 2015 GUESTCRITIC A Tribute to Linda Nochlin by Maura Reilly Linda Nochlin (b. 1931) grew up an only child in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in a secular, leftist Jewish family where intellectual achievement and artistic appreciation were among the highest goals, along with social justice. Of her youth, Nochlin recalled in a recent email to me: We lived near Ebbets Field and whenever the Dodgers made a home run all the ornaments on the mantelpiece shook from the wild applause. We little girls did a lot of roller-skating and jump rope. We were a cultured group all right. I took piano lessons from the same person who had taught my mother. Bach was and still is my super favorite. In high school, my friend Paula and I would take the subway up to the Cloisters on Sunday for the medieval music concerts. Ballet lessons in Manhattan on Saturdays and lots of ballet and modern dance recitals—Martha Graham and José Limón—with my mother or friends. My friend Ronny and I went to hear our adored Wanda Landowska play harpsichord from the back row of City Center and then threw roses at her. Also Lewisohn Stadium. Took lots of trips to [the] Brooklyn Museum, both for ethnic dance performances and, of course, for art. Remember especially the exhibition “100 Artists and Walkowitz” in 1944 because my grandfather knew artist Abraham Walkowitz and introduced me. Many, many trips to the new Brooklyn Public Library, often with my grandfather who liked Irish authors like Lord Dunsany, but also James T. -

Three Evenings in Honor of Linda Nochlin ’51 on the Occasion of the 70Th Anniversary of Her Graduation from Vassar

Three Evenings In Honor of Linda Nochlin ’51 On the Occasion of the 70th Anniversary of her Graduation from Vassar Linda Nochlin’51 March 11 March 18 March 25 taught at Vassar from 1952 7:00 – 8:15 p.m. EST 7:00 – 8:15 p.m. EST 7:00 – 8:15 p.m. EST until 1980, afterwards holding Women Picturing The Paintress’s Studio: Listening to positions at the Graduate Women: From Personal The Woman Artist Linda Nochlin Center of the City of New Spaces to Public Ventures and the Medium York, Yale University, and the Susan Casteras ’71 Patricia Phagan Ewa Lajer-Burcharth PROFESSOR OF ART EMERITA Institute of Fine Arts at New UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON WILLIAM DORR BOARDMAN PHILIP AND LYNN STRAUS ’46 FORMER CURATOR OF PAINTINGS PROFESSOR OF FINE ART York University. While at CURATOR OF PRINTS AND DRAWINGS YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART DIRECTOR OF GRADUATE STUDIES FRANCES LEHMAN LOEB ART CENTER YALE UNIVERSITY Vassar, she wrote to call for a DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF VASSAR COLLEGE Nochlin Student 1967-1968, 1969-1971 ART AND ARCHITECTURE feminist art history, Why Have Nochlin Student 1981-1983 Research Assistant 1975-1977 HARVARD UNIVERSITY There Been No Great Women Nochlin Student 1982-1992 Artists? published in ARTNews T. Barton Thurber Molly Nesbit ’74 ANNE HENDRICKS BASS DIRECTOR Molly Nesbit ’74 PROFESSOR OF ART ON THE in January, 1971. This led to FRANCES LEHMAN LOEB ART CENTER MARY CONOVER MELLON CHAIR PROFESSOR OF ART ON THE VASSAR COLLEGE VASSAR COLLEGE research into forgotten and MARY CONOVER MELLON CHAIR Nochlin Student 1970-1974 VASSAR COLLEGE underappreciated women artists Drawing from the permanent collection of the Nochlin Student 1970-1974 throughout history and, more Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center, curator Patricia Julia Trotta The lecture discusses the reinvention of the broadly, raised consciousness Phagan has selected only images of women by female FILMMAKER artists from the seventeenth century to the 1960s, medium in the work of some contemporary DIRECTOR, LINDA NOCHLIN female painters. -

Revisiting Womanho Use

REVISITING WOMANHO USE Welcome to the (Deconstructed) Dollhouse By Temma Balducci omanhouse, an installation/performance piece interest? Putting aside any prejudice toward the presumed produced by Miriam Schapiro (b. 1923), Judy Chicago essentialism of the 1970s, there is the fact of its ephemeral (b. 1939), and young artists in the Feminist Art nature. Because most of the work for the project was destroyed Program at the California Institute of the Arts, was opened to shortly after the exhibition closed, scholars today are unable to viewers at 533 Mariposa Street in Hollywood, California, from visit the site, walk through and examine its rooms, or January 30 to February 28, 1972.1 The work attracted thousands experience the various performances that took place there. It is of visitors and was the first feminist work to receive national thus difficult to imagine its impact on the artists as well as the attention when it was reviewed in Time magazine.2 Within the visitors/ viewers, many of whom, according to some accounts, history of feminist art, however, Womanhouse has generated scant were moved to tears. The surviving remnants-a 1974 film, scholarly notice. Judy Chicago's The Dinner Party (1979) has photographs, The Dollhouse and other artifacts, and the instead become the exemplar of 1970s feminist art, often being occasional revived performances--evoke increasingly remote reproduced in introductory survey texts as the sole illustration of memories of the original. The work is also likely to be easily feminist art. Undoubtedly, this lack of interest in Womanhouse overlooked because there is no single artist's name attached to and other early feminist works stems in part from continued it. -

LindaNochlin

CRITICS PAGE JULY 13TH, 2015 Linda Nochlin b y Deborah Kas s In 1996 I was invited to speak about my work at the prestigious Institute of Fine Arts at NYU in front of a new generation of scholars, art historians working towards their Ph.D.s. It was the academic home of the great and revolutionary mind of Linda Nochlin. Deborah Kass, Orange Disaster (Linda Nochlin) (1997). Silkscreen, ink, and acrylic on canvas.120 × 150 inches (120 × 75 inches each canvas). Photo: Josh Nefsky. Courtesy the artist and Paul Kasmin Gallery. At that point I was right in the middle of my eight-year-long Warhol project. A question was asked, I believe by Linda herself (I don’t quite remember, only that I addressed my answer directly to her). “How do you decide who to paint?” The answer was easy and somewhat practiced, but this time there was an opportunity too delicious to pass up, if only I handled -

Is Authenticity Authentic?

Is Authenticity Authentic? Sandra Hansen Are questions about authenticity authentic? The question of whether a piece of art is authentic is often raised when critiquing artwork. Originally the question of authenticity came from Linda Nochlin out of a concern for the use of art as an instrument of oppression by imperialist powers. It is important for people to question their own motives about the art that they are creating. However, the word authenticity is over-used, over simplified and stifling. Questions about authenticity becomes an impediment to creativity when artists are prevented from borrowing ideas from other artists, or cultures, and from carrying on conversations about their art. I will first define authenticity. Then I will review the origin of the concept of authenticity and the problems it was trying to address. I will then show some of the problems of using a too rigid application of authenticity. Reaching back into history, in 1896 Leo Tolstoy wrote in his book, What is Art? that, artwork is only authentic when an artwork expresses the authentic values of its maker, especially when, those values are shared by the artist's immediate community. He defined inauthentic work as falsely sentimental and manipulative; while sincerely expressive art, embodies an element of personal commitment (Tolstoy). But where one ends and the other begins is almost impossible to discern. Joel Rudinow in his article, “Race, Ethnicity, Expressive Authenticity: Can White Men Sing the Blues?” wrote, “Authenticity is a value, a species of the genus credibility. It is the kind of credibility that comes from having the appropriate relationship to an original source” (Rudinow 1994). -

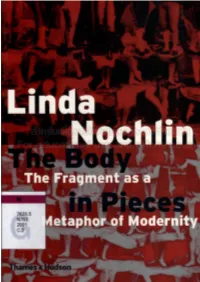

The Fragment As a Metaphor of Modernity

I THIS IS THE TWENTY/SIXTH OF THE WALTER NEURATH MEMORIAL LECTURES WHICH ARE GIVEN ANNUALLY EACH SPRING ON SUBJECTS REFLECTING THE INTERESTS OF THE FOUNDER OF THAMES AND HUDSON THE DIRECTORS OF THAMES AND HUDSON WISH TO EXPRESS THEIR GRATITUDE TO THE TRUSTEES OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON, FOR GRACIOUSLY HOSTING THESE LECTURES THE BODY IN PIECES THE FRAGMENT AS A METAPHOR OF MODERNITY LINDA NOCHLIN THAMES AND HUDSON Any copy of this book issued by the publisher as a paperback is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including these words being imposed on a subsequent purchaser. © 1994 Linda Nochlin First published in the United States of America in 1995 by Thames and Hudson Inc., S00 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10110 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 94^61110 isbn 0^500^55027^1 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system,without prior permission in writing from the publisher. Printed and bound in Great Britain I would like to express my thanks to M rs Eva Neurath and the Neurath family for inviting me to give the 1994 Walter Neurath Memorial Lecture. I never knew Walter Neurath, but the distinction and the rich variety of the books published by Thames and Hudson surely attest to the high standard he established in founding the firm. -

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’S Collaborative Art + Community

TOGETHER, AGAIN Women’s Collaborative Art + Community BY CAREY LOVELACE We are developing the ability to work collectively and politically rather than privately and personally. From these will be built the values of the new society. —Roxanne Dunbar 1 “Female Liberation as the Basis for Social Liberation,” 1970 Cheri Gaulke (Feminist Art Workers member) has developed a theory of performance: “One plus one equals three.” —KMC Minns 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” 1979 3 “All for one and one for all” was the cheer of the Little Rascals (including token female Darla). Our Gang movies, with their ragtag children-heroes, were filmed during the Depression. This was an age of the collective spirit, fostering the idea that common folk banding together could defeat powerful interests. (Après moi, Walmart!) Front Range, Front Range Women Artists, Boulder , CO, 1984 (Jerry R. West, Model). Photo courtesy of Meridel Rubinstein. The artists and groups in Making It Together: Women’s Collaborative Art and Community come from the 1970s, another era believing in communal potential. This exhibition covers a period stretching 4 roughly from 1969 through 1985, and those featured here engaged in social action—inspiringly, 1 In Robin Morgan, Sisterhood Is Powerful: An Anthology of Writings from the Women’s Liberation Movement (New York: Vintage Books, 1970), 492. 2 “Moving Out Part Two: The Artists Speak,” Spinning Off, May 1979. 3 Echoing the Three Muskateers. 4 As points of historical reference: NOW was formed in 1966, the first radical Women’s Liberation groups emerged in 1967. The 1970s saw a range of breakthroughs: In 1971, the Supreme Court decision Roe v.