Texans Getting Academically Prepared (Tgap)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The School Curriculum and Sats in England: Reforms Since 2010

BRIEFING PAPER Number 06798, 26 February 2016 The school curriculum By Nerys Roberts and SATs in England: Reforms since 2010 PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Inside: 1. Overview: the school curriculum in England 2. Background to the national curriculum review in 2011 onwards 3. Reforms to the national curriculum tests (SATs) and the way pupils are assessed Annex: development of the National Curriculum www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 06798, 26 February 2016 2 Contents Summary 3 What do schools in England have to teach? 3 Changes to the national curriculum from September 2014 3 1. Overview: the school curriculum in England 4 1.1 Maintained schools 4 Statutory requirements for the curriculum at maintained English schools 4 The four key stages of the national curriculum 5 Programmes of study 5 Withdrawing children from particular subjects 5 1.2 Curriculum at academies and free schools 5 1.3 School curricula in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland 6 1.4 What subjects are currently included in the English national curriculum? 7 2. Background to the national curriculum review in 2011 onwards 8 2.1 Reaction to the June 2012 proposals 8 2.2 Further consultation on programmes of study: February and July 2013 9 2.3 July 2013 – second formal consultation 10 2.4 First final curriculum documents published in September 2013 10 2.5 Reform to GCSEs, AS and A Levels 11 3. Reforms to the national curriculum tests (SATs) and the way pupils -

Year Five and Six Parents' Curriculum Meeting

St Joan of Arc RC Primary Year Two and Three Parents’ Curriculum Meeting F R I D A Y 4 TH OCTOBER Aims of the meeting Give you a better understanding of your child’s learning this term Share our aims Help parents/carers to feel empowered to support their children Give you the opportunity to ask questions Introductions Miss Newman– Year 2 and 3 lead. Behaviour lead Supporting classroom teachers Developing good classroom practice Monitoring pupil progress Part of the English and PE teams Homework - Reading At least 10-20 minutes daily in Year Two, and at least 20 minutes daily in Year Three. Signed reading record (comments are really helpful) Discussion about the text Sounding out and applying phonic knowledge Reading around the word Checking for understanding Predicting Inference and deduction Intonation and expression Comprehension cards Reading Records National Curriculum statements at front Signed off by teacher during guided reading Comment in book only if child not meet the statement in the lesson Ideas for home reading in the middle Homework - Reading Roy had waited a long time but nothing was happening. Then suddenly the line jerked. In his excitement he tripped over my bag and fell head first into the water. a. What was Roy doing before he fell? b. Why did he become excited? Homework - Reading By the time we reached the small village the sun was going down. After so long on the road we were glad to be able to take off our boots and rub our sore feet. a. What time of the day was it? b. -

(SSOG): Year Five Report

Nevada System of Higher Education Silver State Opportunity Grant (SSOG) Year 5 Report January 29, 2021 THE NEVADA SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION Board of Regents Dr. Mark W. Doubrava, Chair Mrs. Carol Del Carlo, Vice Chair Mr. Joseph C. Arrascada Mr. Patrick J. Boylan Mr. Byron Brooks Dr. Patrick R. Carter Ms. Amy J. Carvalho Dr. Jason Geddes Mrs. Cathy McAdoo Mr. Donald Sylvantee McMichael Sr. Mr. John T. Moran Ms. Laura E. Perkins Dr. Lois Tarkanian Officers of the Nevada System of Higher Education Dr. Melody Rose, Chancellor Dr. Keith Whitfield, President Mr. Brian Sandoval, President University of Nevada, Las Vegas University of Nevada, Reno Mr. Bart J. Patterson, President Dr. Federico Zaragoza, President Nevada State College College of Southern Nevada Ms. Joyce M. Helens, President Dr. Karin M. Hilgersom, President Great Basin College Truckee Meadows Community College Dr. Vincent R. Solis, President Dr. Kumud Acharya, President Western Nevada College Desert Research Institute 2 The Silver State Opportunity Grant Program Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................................................................. 4 BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 ELIGIBILITY ........................................................................................................................................................................ -

Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Healthy Futures Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation BY THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PREPARED BY: Anna E. Davis, BA Deborah F. Perry, PhD Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development 3300 Whitehaven Street, NW, Suite 3300 Washington, DC 20007 SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 Acknowledgements e want to acknowledge the ongoing contributions of Dr. Meghan Sullivan, program evaluator at the DC Department of Behavioral Health, for managing all of the data Wfrom the consultants in the field. We also appreciate the support of members of the Project LAUNCH team from the DC Departments of Health and Behavioral Health—especially Barbara Parks and Vinetta Freeman. Finally, we are grateful for the excellent work of the four mental health consultants as well as Dr. Shana Bellow who provides them with clinical and reflective supervision. HEALTHY FUTURES: YEAR FOUR EVALUATION 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................................................7 The Evidence -

Early Years – Key Stage 4

Public Oral Health CURRIC ULUM TOOL KIT WWW... Early Years – Key Stage 4 Oral Health Promotion Team Derby City and Derbyshire County Public Contents • Introduction Page 2 • Oral Health messages Pages 3-5 • Oral Health links to the Early Years Foundation Stage Page 7 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 1 Page 9 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 2 Page 10 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 3 Page 11 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 4 Page 12 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Early Years - Key Stage 4 Page 14 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Special Educational Page 15 Needs and Disabilities and English as an Additional Language • Borrowing resources Page 16 • Purchasing Resources Page 17 • Apps available to download Page 18 1 Public Introduction Schools provide an important setting for promoting health which can easily be integrated into general health promotion, school curriculum and activities. Health promoting messages can be reinforced throughout the most influential stages of children’s lives, enabling them to develop lifelong sustainable attitudes, behaviours and skills. The health and wellbeing of school staff, families and community members can also be enhanced by programmes based in schools. Oral health is fundamental to general health and wellbeing. A healthy mouth enables an individual to speak, eat and socialize without experiencing active disease, discomfort or embarrassment. Poor oral health impacts on children’s confidence, language and personal, social and emotional development. Tackling poor oral health is a priority for Public Health England (PHE) under the national priority of ensuring that every child has the Best Start in Life. -

Opening a Studio School a Guide for Studio School Proposer Groups on the Pre-Opening Stage

Opening a studio school A guide for studio school proposer groups on the pre-opening stage August 2014 Contents Introduction 3 Section 1 - Who does what - roles and responsibilities? 5 Section 2 - Managing your project 10 Section 3 – Governance 12 Section 4 - Pupil recruitment and admissions 21 Section 5 - Statutory consultation 33 Section 6 - Staffing and education plans 36 Section 7 - Site and buildings 42 Section 8 – Finance 56 Section 9 - Procurement and additional support 63 Section 10 - Funding Agreement 67 Section 11 - The equality duty 71 Section 12 - Preparing to open 73 Section 13 - Once your school is open 80 Annex A - RSC regions and Local authorities 82 2 Introduction Congratulations! All your planning and preparation has paid off, and the Secretary of State for Education has agreed that your application to open a studio school should move to the next stage of the process – known as the ‘pre-opening’ stage. This is the stage between the approval of your application and the opening of the school. The setting up of a studio school is a challenging but ultimately very rewarding task and it will require significant commitment and time from sponsors and partners. Your original application set out your plans for establishing the studio school, from the education vision and the admission of pupils to the recruitment of staff and the curriculum. Now your application has been approved, you must begin work to implement these plans. The letter of approval you received from the Department for Education (DfE) sets out important conditions of approval. It is vital that you consider these conditions carefully in planning your priorities and what you need to focus on next. -

School Admissions in England: State-Funded Schools

BRIEFING PAPER Number 07147, 11 January 2016 School admissions in By Nerys Roberts England: state-funded mainstream schools PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Inside: 1. Background to school admissions in England and the legal framework 2. Applying for a school place in the normal round 3. How admission authorities rank applicants 4. Parents unhappy with offered school place 5. Statistics on school place offers for 2015/16 6. Schools Adjudicator report www.parliament.uk/commons-library | intranet.parliament.uk/commons-library | [email protected] | @commonslibrary Number 07147, 11 January 2016 2 Contents Summary 3 1. Background to school admissions in England and the legal framework 4 1.1 Admission authorities and statutory admissions framework 4 Application of school admissions codes to academies and free schools 4 1.2 Determining admission arrangements 5 2. Applying for a school place in the normal round 6 2.1 School starting age in England 7 Summer born children starting school 7 Deferring a reception place, or attending part-time initially 7 2.2 How far in advance do parents have to apply for a place? 8 2.3 Guidance for parents and carers on school admission process 8 2.4 Selecting schools: naming preferred schools on the application form 8 Myths about naming more than one school on the application form 9 Nominating schools in other local authority areas 9 2.5 When a child has two addresses because of shared care 9 2.6 Moving into the area after the application deadline 9 2.7 School places for children returning or arriving from abroad 9 2.8 Obtaining a school place dishonestly 10 3. -

Tobbelltransition.Pdf

University of Huddersfield Repository Tobbell, Jane Transition from primary to secondary school: a case study from the United Kingdom Original Citation Tobbell, Jane (2014) Transition from primary to secondary school: a case study from the United Kingdom. In: Facetten von Übergängen im Bildungssystem Nationale und internationale Ergebnisse empirischer Forschun. Waxmann, Münster, Germany, pp. 251-264. ISBN 978-3-8309-3063-1 This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/21064/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Tobbell, J. (2014) The Transition from Primary to Secondary School: a case study from the United Kingdom in Liegmann, A.B., Mammes, I. and Racherbäumer, K. eds (2014) Facetten von Übergängen im Bildungssystem:Nationale und internationale Ergebnisse empirischer Forschung, Waxmann:Münster ISBN 978-3-8309-3063- Transition from primary to secondary school: a case study from the United Kingdom This chapter presents ethnographic research from a project which followed children in a UK primary school in their final year (referred to as year six, children are 10 and 11 years old) in primary school to their first year in secondary school (referred to as year seven, children are 11 and 12 years old). -

What Happened the Six Dimensions Project Report 2018 Nick Allen

What Happened The Six Dimensions Project Report 2018 Nick Allen June 2018 SFCA works to lead and support a thriving and sustainable Sixth Form College sector by being an effective advocate, adviser and information provider for members and a reliable and authoritative source of insight, data and expertise for policy-makers and opinion-formers. For more information about this report please contact Vanessa Donhowe: Sixth Form Colleges Association 8th Floor 50 Broadway London SW1H 0RG 020 3824 0468 [email protected] sixthformcolleges.org © Sixth Form Colleges Association What Happened The Six Dimensions Project Report 2018 Contents Chapter One: Known Knowns, Known Unknowns and Unknown Unknowns Revisited Chapter Two: Retention on Two Year A level Courses Chapter Three: Performance in Linear A levels in Sixth Form Colleges Chapter Four: The Quality of Equality Chapter Five: The Gender Agenda Chapter Six: Programmes of Study and Patterns of Enrolment Appendix One: Understanding Six Dimensions Reports Introduction In the autumn of 2017, What Happened, Hillary Clinton’s account of the 2016 election campaign was published. It had a rather good and deliberately ambiguous title, interpretable in whole range of ways. From a gentle, enquiring ‘so what happened’, to a forensically analytical ‘what happened?’, through to a raging primal scream of ‘what happened?’. In Hilary’s case, Trump happened, and the interpretation of how that happened will keep psephologists busy for some time. Last year, something significant happened to us. It may not have been Trump sized, but nevertheless, the conclusion of the first round of A level reform represents a fundamental shift in the landscape, and understanding and navigating this shift represents a vital challenge for colleges. -

Primary and Secondary Textbook Complexity in England

Research Brief Primary and Secondary Textbook Complexity in England Heather Koons, Ph.D., Director of Research Services; Laura Bush, Research Specialist; and Eleanor E. Sanford-Moore, Ph.D., Senior Vice President, Research and Development speak to the accessibility of the content. If year three pupils are ABSTRACT presented with reading materials at a level of complexity above their The study examined the text complexity of textbooks available for reading ability level, learning the material could be quite challenging. use in English maintained primary and secondary schools that Conversely, materials written significantly below a pupil’s ability level address select mandatory courses: English, mathematics, science, may foster boredom in the classroom and limit the pace of learning. history, geography and citizenship, for years one through 11, key A first step in understanding the relationship between pupils and stages 1 through 4. text is to understand the text complexity of the materials. This is the purpose of the current study. The research hypothesis was that text complexity varies within school year and key stage and that the median text complexity increases with school year/key stage. The results supported the hypothesis. MATERIALS However the findings highlight the fact that the greatest increase in The unit of analysis in this study was textbooks (N = 211) available complexity across the years and key stages occurs early on when for use in England’s primary and secondary schools. An effort was young readers are still developing their reading skills: between years made to obtain textbooks written specifically for the new 2015 one and two and between key stage 1 and 2. -

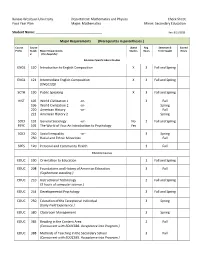

Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education

Kansas Wesleyan University Department: Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education Student Name: _____________________________________ Rev. 8/31/2018 Major Requirements (Prerequisites in parentheses.) Course Course Liberal Req. Semester & Earned Prefix Numb Major Requirements Studies Hours Term Taught Hours er (Pre-Requisite) Education Specific Liberal Studies ENGL 120 Introduction to English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring ENGL 121 Intermediate English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring (ENGL120) SCTH 130 Public Speaking X 3 Fall and Spring HIST 105 World Civilization 1 -or- 3 Fall 106 World Civilization 2 -or- Spring 220 American History -or- Fall 221 American History 2 Spring SOCI 131 General Sociology -or- No 3 Fall and Spring PSYC 101 The World of You: An Introduction to Psychology Yes SOCI 240 Social Inequality -or- 3 Spring 250 Racial and Ethnic Minorities Fall SPES 120 Personal and Community Health 3 Fall Education Courses EDUC 100 Orientation to Education 1 Fall and Spring EDUC 208 Foundations and History of American Education 3 Fall (Sophomore standing.) EDUC 210 Instructional Technology 2 Fall and Spring (3 hours of computer science.) EDUC 244 Developmental Psychology 3 Fall and Spring EDUC 250 Education of the Exceptional Individual 3 Spring (Early Field Experience.) EDUC 380 Classroom Management 3 Spring EDUC 385 Reading in the Content Area 2 Fall (Concurrent with EDUC388. Acceptance into Program.) EDUC 388 Methods of Teaching in the Secondary School 3 Fall (Concurrent with -

Twenty Outstanding Primary Schools Excelling Against the Odds This Report Was Produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, Consultant and Former Her Majesty’S Inspector

Twenty outstanding primary schools Excelling against the odds This report was produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, consultant and former Her Majesty’s Inspector. © Crown copyright 2009 Contents Foreword 2 Pictures of success: the outstanding schools 59 Ash Green Primary School, Calderdale 60 Summary 3Banks Road Primary School, Liverpool 61 Berrymede Junior School, Ealing 62 Characteristics of outstanding primary Bonner Primary School, Tower Hamlets 63 schools in challenging circumstances 5 Cotmanhay Infant School, Derbyshire 64 Introduction 6 Cubitt Town Junior School, Tower Hamlets 65 Selecting the schools 6 Gateway Primary School, Westminster 66 Primary schools in challenging circumstances 8 John Burns Primary School, Wandsworth 67 Unearthing the secrets of success 9 Michael Faraday School, Southwark 68 Ramsden Infant School, Cumbria 69 St John the Divine Church of England Primary School, 11 Achieving excellence Lambeth 70 Raising attainment and achievement 12 St Monica’s Catholic Primary School, Sefton 71 Making teaching and learning consistently effective 13 St Paul’s Peel Church of England Primary School, Providing a broad, balanced, relevant and stimulating Salford 72 curriculum 15 St Sebastian’s Catholic Primary School and Nursery, Assessing and tracking progress 18 Liverpool 73 Attracting and appointing effective staff 20 Shiremoor Primary School, North Tyneside 74 Transformational leadership 20 Simonswood Primary School, Knowsley 75 From good to great 25 The Orion Primary School, Barnet 76 Welbeck Primary School, City of