Ofsted Annual Report: Early Years 2015; Ofsted, July 2015;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Texans Getting Academically Prepared (Tgap)

TEXANS GETTING ACADEMICALLY PREPARED (TGAP) Year Six Evaluation Report September 2004 – August 2005 March 2006 Prepared for Texas Education Agency By Texas Center for Educational Research Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston TEXANS GETTING ACADEMICALLY PREPARED (TGAP) Year Six Evaluation Report September 2004 – August 2005 March 2006 Prepared for Texas Education Agency Prepared By Texas Center for Educational Research Center for Public Policy at the University of Houston ©Texas Center for Educational Research Credits Texas Center for Educational Research Contributing Authors The Texas Center for Educational Research Texas Center for Educational Research (TCER) conducts and communicates nonpartisan Kelly Shapley, Ph.D. research on education issues to serve as an Keith Sturges, MAA independent resource for those who make, Daniel Sheehan, Ed.D. influence, or implement education policy in Texas. A 15-member board of trustees governs the Center for Public Policy research center, including appointments from the at the University of Houston Texas Association of School Boards, Texas Gregory R. Weiher Association of School Administrators, and State Christina Hughes Board of Education. Joseph Howard For additional information about TCER research, please contact: Prepared for Kelly S. Shapley, Director Texas Center for Educational Research Texas Education Agency 12007 Research Blvd. 1701 N. Congress Avenue P.O. Box 679002 Austin, Texas 78701-1494 Austin, Texas 78767-9002 Phone: 512-463-9734 Phone: 512-467-3632 or 800-580-8237 Fax: 512-467-3658 Research Funded by Reports are available on the TCER Web Site at www.tcer.org Texas Education Agency Texans Getting Academically Prepared (TGAP) Year Six Executive Summary..................................................................................................................... -

Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation

Healthy Futures Year Four Evaluation of Early Childhood Mental Health Consultation BY THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF BEHAVIORAL HEALTH PREPARED BY: Anna E. Davis, BA Deborah F. Perry, PhD Georgetown University Center for Child and Human Development 3300 Whitehaven Street, NW, Suite 3300 Washington, DC 20007 SEPTEMBER 30, 2014 Acknowledgements e want to acknowledge the ongoing contributions of Dr. Meghan Sullivan, program evaluator at the DC Department of Behavioral Health, for managing all of the data Wfrom the consultants in the field. We also appreciate the support of members of the Project LAUNCH team from the DC Departments of Health and Behavioral Health—especially Barbara Parks and Vinetta Freeman. Finally, we are grateful for the excellent work of the four mental health consultants as well as Dr. Shana Bellow who provides them with clinical and reflective supervision. HEALTHY FUTURES: YEAR FOUR EVALUATION 1 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................................................................1 Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................................5 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................................................................7 The Evidence -

Early Years – Key Stage 4

Public Oral Health CURRIC ULUM TOOL KIT WWW... Early Years – Key Stage 4 Oral Health Promotion Team Derby City and Derbyshire County Public Contents • Introduction Page 2 • Oral Health messages Pages 3-5 • Oral Health links to the Early Years Foundation Stage Page 7 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 1 Page 9 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 2 Page 10 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 3 Page 11 • Oral Health links to the National Curriculum: Key Stage 4 Page 12 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Early Years - Key Stage 4 Page 14 • Interactive Oral Health activities/ Downloadable resources: Special Educational Page 15 Needs and Disabilities and English as an Additional Language • Borrowing resources Page 16 • Purchasing Resources Page 17 • Apps available to download Page 18 1 Public Introduction Schools provide an important setting for promoting health which can easily be integrated into general health promotion, school curriculum and activities. Health promoting messages can be reinforced throughout the most influential stages of children’s lives, enabling them to develop lifelong sustainable attitudes, behaviours and skills. The health and wellbeing of school staff, families and community members can also be enhanced by programmes based in schools. Oral health is fundamental to general health and wellbeing. A healthy mouth enables an individual to speak, eat and socialize without experiencing active disease, discomfort or embarrassment. Poor oral health impacts on children’s confidence, language and personal, social and emotional development. Tackling poor oral health is a priority for Public Health England (PHE) under the national priority of ensuring that every child has the Best Start in Life. -

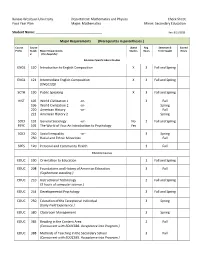

Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education

Kansas Wesleyan University Department: Mathematics and Physics Check Sheet Four Year Plan Major: Mathematics Minor: Secondary Education Student Name: _____________________________________ Rev. 8/31/2018 Major Requirements (Prerequisites in parentheses.) Course Course Liberal Req. Semester & Earned Prefix Numb Major Requirements Studies Hours Term Taught Hours er (Pre-Requisite) Education Specific Liberal Studies ENGL 120 Introduction to English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring ENGL 121 Intermediate English Composition X 3 Fall and Spring (ENGL120) SCTH 130 Public Speaking X 3 Fall and Spring HIST 105 World Civilization 1 -or- 3 Fall 106 World Civilization 2 -or- Spring 220 American History -or- Fall 221 American History 2 Spring SOCI 131 General Sociology -or- No 3 Fall and Spring PSYC 101 The World of You: An Introduction to Psychology Yes SOCI 240 Social Inequality -or- 3 Spring 250 Racial and Ethnic Minorities Fall SPES 120 Personal and Community Health 3 Fall Education Courses EDUC 100 Orientation to Education 1 Fall and Spring EDUC 208 Foundations and History of American Education 3 Fall (Sophomore standing.) EDUC 210 Instructional Technology 2 Fall and Spring (3 hours of computer science.) EDUC 244 Developmental Psychology 3 Fall and Spring EDUC 250 Education of the Exceptional Individual 3 Spring (Early Field Experience.) EDUC 380 Classroom Management 3 Spring EDUC 385 Reading in the Content Area 2 Fall (Concurrent with EDUC388. Acceptance into Program.) EDUC 388 Methods of Teaching in the Secondary School 3 Fall (Concurrent with -

Twenty Outstanding Primary Schools Excelling Against the Odds This Report Was Produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, Consultant and Former Her Majesty’S Inspector

Twenty outstanding primary schools Excelling against the odds This report was produced by Ofsted with Dr Peter Matthews, consultant and former Her Majesty’s Inspector. © Crown copyright 2009 Contents Foreword 2 Pictures of success: the outstanding schools 59 Ash Green Primary School, Calderdale 60 Summary 3Banks Road Primary School, Liverpool 61 Berrymede Junior School, Ealing 62 Characteristics of outstanding primary Bonner Primary School, Tower Hamlets 63 schools in challenging circumstances 5 Cotmanhay Infant School, Derbyshire 64 Introduction 6 Cubitt Town Junior School, Tower Hamlets 65 Selecting the schools 6 Gateway Primary School, Westminster 66 Primary schools in challenging circumstances 8 John Burns Primary School, Wandsworth 67 Unearthing the secrets of success 9 Michael Faraday School, Southwark 68 Ramsden Infant School, Cumbria 69 St John the Divine Church of England Primary School, 11 Achieving excellence Lambeth 70 Raising attainment and achievement 12 St Monica’s Catholic Primary School, Sefton 71 Making teaching and learning consistently effective 13 St Paul’s Peel Church of England Primary School, Providing a broad, balanced, relevant and stimulating Salford 72 curriculum 15 St Sebastian’s Catholic Primary School and Nursery, Assessing and tracking progress 18 Liverpool 73 Attracting and appointing effective staff 20 Shiremoor Primary School, North Tyneside 74 Transformational leadership 20 Simonswood Primary School, Knowsley 75 From good to great 25 The Orion Primary School, Barnet 76 Welbeck Primary School, City of -

Download Whole School Change

Whole School Change Outline In the 2005/06 academic year four Creative Partnerships London East schools were awarded substantial funding awards to realise change in their schools. The London Multimedia Lab at the London School of Economics was commissioned to track the outcomes of the four projects measured against the Creative Partnerships DCMS Policy and Delivery Agreement. These findings are available in a summary report entitled ‘Pathways to Value’. The rationale behind offering schools the opportunity to apply for funding for large-scale projects was to encourage accelerated Whole Change School Hannah Wilmot change. This case study explores definitions of whole school change, how effective the projects were in supporting whole school change, and what changes were sustainable after the project was completed. The case study includes recommendations for other schools embarking on large-scale change projects. Creative Partnerships Creative London East and South Case Studies Introduction The Schools For the first time, in 2005/06, Creative Partnerships London East1 Columbia is a large primary school in Tower Hamlets. The majority offered its schools the opportunity to apply for funding for large- of pupils are from Muslim backgrounds and almost two-thirds are scale projects to support whole school change. Based on the Bangladeshi. More than half the pupils are at an early stage of strength of applications and agreed by an independent panel, learning English. Ofsted recently reported, ‘Columbia is a good four schools were awarded a substantial amount to support such and improving school. It now has a number of outstanding features projects. Each school planned a piece of work with a range because of the headteacher’s relentless focus on improving its of creative partners to explore and develop models, systems performance’. -

Ofsted - Office for Standards in Education

OFSTED - OFFICE FOR STANDARDS IN EDUCATION The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools Standards and quality in Education 1997/98 Laid before Parliament by the Secretary of State for Education and Employment pursuant to Section 2(7)(a) of the School Inspections Act 1996 Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 February 1999 129 £10.95 Sterling published by The Stationery Office OFSTED - The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools Contents Letter to The Rt Hon David Blunkett MP Preface Commentary Primary schools Secondary schools Sixth forms in schools Special schools Schools requiring special measures and schools with serious weaknesses The education of young people who have disengaged from mainstream education Youth work and adult education Independent schools Teacher education and training Local education authority support for school improvement Annexes Annex 1 Inspection evidence Annex 2 Interpreting inspection evidence Annex 3 The sample of schools Annex 4 1998 Key Stages 1 and 2 test results Annex 5 Achievement of boys and girls in single-sex and mixed schools Annex 6 Average improvement trend between 1995 and 1998 against eligibility for free school meals Annex 7 Statistical Summary Annex 8 GCSE scores for different subjects in secondary schools Annex 9 OFSTED Publications 1997/98 OFSTED - The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools OFSTED - The Annual Report of Her Majesty's Chief Inspector of Schools Preface This Report draws on three sources of evidence: Section 10 inspections carried out by registered inspectors; inspections carried out by Her Majesty's Inspectors of Schools (HMI); research reviews commissioned by OFSTED. -

Teaching in the Early Years of Practice: a Five-Year Longitudinal

Teaching in the Early Years of Practice: A Five-Year Longitudinal Study www.teachers.ab.ca AN ATA RESEARCH UPDATE: JUNE 2013 RESEARCH UPDATE: ATA AN © Copyright 2013 Unauthorized use or duplication without prior approval is strictly prohibited. ISBN 978-1-927074-17-6 The Alberta Teachers’ Association 11010 142 Street NW, Edmonton, AB T5N 2R1 Telephone 780-447-9400 or 1-800-232-7208 www.teachers.ab.ca Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 3 Purpose of the Study ....................................................................................................................... 3 Study Design .................................................................................................................................. 3 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 3 Key Findings ................................................................................................................................... 4 What It’s Like to Be a New Teacher ........................................................................................... 4 Supports Available at the School Level ..................................................................................... 4 Supports -

OFSTED and HMI 1.1 Ofsted Priority

Report on the Curriculum June 2016 Tessa Browning The Summer Term has involved a redeployment of some staff following the extended absence of Mr Callaghan. Mrs Nightingale and Mrs Browning have taught the Hare class, with the support of Mrs Taylor and Mrs Dudfield. The TE Day was spent looking at emotional health, particularly Growth Mindsets as well as how we may improve children’s speaking and listening skills. In house professional development has also focussed upon gaining a better understanding of the new curriculum, particularly the end of key stage one assessment. We have also had a visit from Mr Hill (awaiting report) which was successful. Key Stage One assessments have also been moderated, and the County found our assessments to be accurate. SECTION ONE: OFSTED AND HMI 1.1 Ofsted Priority One: Improve the quality of teaching across the school in order to accelerate progress in all subjects, and particularly in writing and mathematics, by making sure teachers: check on the progress of all groups during lessons to pick up and address errors or misconceptions as they occur use assessment accurately so that they can provide appropriately demanding work for all pupils, but particularly the most-able, at all times give pupils clear feedback through marking to show how they can improve their work encourage pupils to try to work problems out for themselves and not simply wait for adults to come and support them or tell them the answer. In the last report it was stated that we were looking in to doing NfER tests in the Summer term so that we have a national baseline for comparison. -

Sre Primary Curriculum Overview

SRE PRIMARY CURRICULUM OVERVIEW FOUNDATION KEY STAGE ONE KEY STAGE TWO STAGE Early Years Year One Year Two Year Three Year Four Year Five Year Six Myself and Myself and Differences: Boys Self Esteem Growing and Talking about Puberty and Others Others and girls Changing puberty reproduction Family Networks Body Parts Differences: Male Challenging Body changes Becoming men Relationships and Female Gender and reproduction and women and reproduction Stereotypes Body Awareness Family Naming Body Differences: Male What is puberty? Puberty and Conception and Parts and Female hygiene pregnancy TOPICS Hygiene Friendships Everybody needs Family Thinking, feeling, Menstruation and Being a parent caring for Differences doing – changing wet dreams relationships Choices Looking after the Decision Making Assertiveness Menstruation HIV body education for Transmission girls Safety Your questions Building good Your questions answered relationships answered Include assessment opportunities in every lesson and at the end each unit. See section 4 on assessment Foundation Stage Learning Intentions and Outcomes Early Years Foundation Stage Links Suggested Resources Unit One: PSE Early Years Foundations Stage, Sex and Myself and Others Self confidence and self esteem Relationship Education Scheme of Work for Making Relationships Foundation Stage, Key Stage 1 and Key Learning Intention: Behaviour and Self Control Stage 2, Croydon Healthy Schools To recognise some feelings. Sense of Community To recognise that their behaviour affects other The whole Foundation Stage Unit is taken people, especially when angry. with kind permission from the Croydon Scheme of Work. Learning Outcomes: To begin to have identified some of their feelings and recognised some of the ways they express them. -

A Literature Review of the Value of Vocational Qualifications

Final Report A literature review of the value of vocational qualifications National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) A literature review of the value of vocational qualifications Sarah Lynch David Sims Karen Wespieser Published in June 2015 By the National Foundation for Educational Research, The Mere, Upton Park, Slough, Berkshire SL1 2DQ www.nfer.ac.uk © 2015 National Foundation for Educational Research Registered Charity No. 313392 ISBN 978 1 910008 72 0 How to cite this publication: Lynch, S., Sims, D. and Wespieser, K. (2015). A Literature Review of the Value of Vocational Qualifications. Slough: NFER. Contents Executive summary v Review methods v Key findings vi Benefits for learners vi Benefits for business vii Benefits for the economy vii Conclusions and recommendations vii 1 Introduction 9 1.1 Aims of the review 9 1.2 Review methods 10 1.3 Report structure 11 2 Overview of the studies reviewed 12 2.1 What is the value of vocational qualifications and for whom? 12 2.2 What is the strength of the evidence reviewed? 13 3 The value of vocational qualifications for learners 14 3.1 Value for future employment 14 3.2 Value for future earnings 18 3.3 Value for future achievement of higher qualifications 22 3.4 Value for benefit reduction 22 4 The value of vocational qualifications for employers and public budgets 24 4.1 The benefits for employers 24 4.2 The benefits for public budgets 25 5 Wider benefits: widening participation in education 26 6 Conclusions and recommendations 28 6.1 Conclusions 28 6.2 Recommendations for further research 29 7 References 31 Appendix A Review parameters and search strategy 32 Appendix B Bibliographies 37 B1 Shortlisted studies 37 B2 Other studies found during searches 39 Appendix C Review template 44 Executive summary The National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) has carried out a small-scale rapid literature review of the value of vocational qualifications offered in the UK by the Joint Council for Qualifications (JCQ) members. -

YEAR SIX Email: [email protected]

School Directors Amanda Ilhan Pre School & Primary School Deputy Director Phone: (0212) 2027027 Email: [email protected] Richard I’Anson Pre School & Primary School Director Phone: (0212) 2575136 Etiler Campus Email: [email protected] William Bradley Secondary Director Phone: (0212) 2027027 Email: [email protected] CURRICULUM Director of Admissions Tuba Güven INFORMATION Registrar Phone: (0212) 2867375 FOR YEAR SIX Email: [email protected] Head of PR/Communications PARENTS Helen Kiran Communications Phone: (0212) 2027027 ext: 175 Email: [email protected] “Eruditio limites permeat” www.bis.k12.tr “Education Transcends Boundaries” Other things you might like to know A Message from the Director and Deputy Director Staffing All our staff are qualified experienced expatriate teachers. With the ex- Dear Parents, ceptions of the teachers of French and Turkish they are all English native Welcome to the British International School Istanbul. speakers mainly from the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the BISI has a caring approach towards children and staff. USA. The atmosphere is purposeful but calm where individ- Assessment uals are valued and respected. In line with the UK our students take their SATs at the end of Year 2 and Year 6. There is also a system of teacher assessment and extensive rec- ord keeping. We hope that you find this booklet useful. We have Reporting based much of our work on the National Curriculum There are two formal written reports each year in December and June, as for England and Wales. In this booklet you will find an well as two Parent/Teacher Consultation evenings in October and April to overview of the National Curriculum and specific infor- discuss the work of your child.